Version for Online Viewing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Шахматных Задач Chess Exercises Schachaufgaben

Всеволод Костров Vsevolod Kostrov Борис Белявский Boris Beliavsky 2000 Шахматных задач Chess exercises Schachaufgaben РЕШЕБНИК TACTICAL CHESS.. EXERCISES SCHACHUBUNGSBUCH Шахматные комбинации Chess combinations Kombinationen Часть 1-2 разряд Part 1700-2000 Elo 3 Teil 1-2 Klasse Русский шахматный дом/Russian Chess House Москва, 2013 В первых двух книжках этой серии мы вооружили вас мощными приёмами для успешного ведения шахматной борьбы. В вашем арсенале появились двойной удар, связка, завлечение и отвлечение. Новый «Решебник» обогатит вас более изысканным тактическим оружием. Не всегда до короля можно добраться, используя грубую силу. Попробуйте обхитрить партнёра с помощью плаща и кинжала. Маскируйтесь, как разведчик, и ведите себя, как опытный дипломат. Попробуйте найти слабое место в лагере противника и в нужный момент уничтожьте защиту и нанесите тонкий кинжальный удар. Кстати, чужие фигуры могут стать союзниками. Умелыми манёврами привлеките фигуры противника к их королю, пускай они его заблокируют так, чтобы ему, бедному, было не вздохнуть, и в этот момент нанесите решающий удар. Неприятно, когда все фигуры вашего противника взаимодействуют между собой. Может, стоить вбить клин в их порядки – перекрыть их прочной шахматной дверью. А так ли страшна атака противника на ваши укрепления? Стоит ли уходить в глухую оборону? Всегда ищите контрудар. Тонкий промежуточный укол изменит ход борьбы. Не сгрудились ли ваши фигуры на небольшом пространстве, не мешают ли они друг другу добраться до короля противника? Решите, кому всё же идти на штурм королевской крепости, и освободите пространство фигуре для атаки. Короля всегда надо защищать в первую очередь. Используйте это обстоятельство и совершите открытое нападение на него и другие фигуры. И тогда жернова вашей «мельницы» перемелют всё вражеское войско. -

Colorado Chess Informant

Volume 39, Number 3 July 2012 / $3.00 Colorado State Chess Association COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT Photo by Michael Wokurka Grandmaster Tejas Bakre receiving his prize winnings from Organizer, Joe Fromme. Grandmaster In The House! Bobby Fischer Saluted www.colorado-chess.com Volume 39, Number 3 Colorado Chess Informant July 2012 From The Editor Whew, it has been a busy past few months for chess in Colorado. When the membership voted to go to an all electronic issue of the Informant, that gave me the ability to expand an issue as The Colorado State Chess Junior Representative: much as the number of articles allowed without incurring any Association, Inc., is a Section Rhett Langseth cost to the CSCA. 501(C)(3) tax exempt, non- 15282 Paddington Circle 44 pages of chess in Colorado awaits you in this issue! That profit educational corporation Colorado Springs, CO 80921 should keep you busy for the next three months. The feature of formed to promote chess in [email protected] this issue is the wonderful “Salute to Bobby Fischer Chess Tour- Colorado. Contributions are Members at Large: nament” that was held in early May and which I was once again tax deductible. Dues are $15 a Frank Deming honored by the Organizer, Joe Fromme, in having selected me as year or $5 a tournament. Youth 7906 Eagle Ranch Road the Tournament Director. Again a premier event all around and (under 21) and Senior (65 or Fort Collins, CO 80528 even more so when we had the pleasure of hosting Grandmaster older) memberships are $10. [email protected] Tejas Bakre from India, who decided to play. -

Detecting Fortresses in Chess

ELEKTROTEHNISKIˇ VESTNIK 79(1-2): 35–40, 2012 ENGLISH EDITION Detecting Fortresses in Chess Matej Guid, Ivan Bratko Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, Faculty of Computer and Information Science, University of Ljubljana, Trzaˇ skaˇ c. 25, Ljubljana, Slovenia Email: [email protected] Abstract. We introduce a computational method for semi-automatical detecting fortresses in the game of chess. It is based on computer heuristic search and can be easily used with any state-of-the-art chess program. We also demonstrate a method for avoiding fortresses and show how to find a break-through plan when one exists. Although the paper is not concerned with the question whether it is practical or not to implement the method within the state-of-the-art chess programs, the method can be useful, for example, in correspondence chess or in composing chess studies, where a human-computer interaction is of great importance, and the time available is significantly longer than in ordinary chess competitions. Keywords: fortress, chess, computer chess, game playing, heuristic search 1 INTRODUCTION In this paper, we will introduce a novel method for detecting fortresses. It is based on computer heuristic In chess, fortresses are usually regarded as positions search. We intend to demonstrate that due to lack when one side has a material advantage, however, the of changes in backed-up heuristic evaluations between defender’s position is an impregnable fortress and the successive depths that are otherwise expected in won win cannot be achieved when both sides play optimally. positions, fortresses can be detected effectively. We will The current state-of-the-art programs typically fail to also show how to avoid fortresses and possibly find a recognise fortresses and seem to claim a winning ad- break-through plan when one exists. -

Move by Move

Cyrus Lakdawala Tal move by move www.everymanchess.com About the Author is an International Master, a former National Open and American Open Cyrus Lakdawala Champion, and a six-time State Champion. He has been teaching chess for over 30 years, and coaches some of the top junior players in the U.S. Also by the Author: Play the London System A Ferocious Opening Repertoire The Slav: Move by Move 1...d6: Move by Move The Caro-Kann: Move by Move The Four Knights: Move by Move Capablanca: Move by Move The Modern Defence: Move by Move Kramnik: Move by Move The Colle: Move by Move The Scandinavian: Move by Move Botvinnik: Move by Move The Nimzo-Larsen Attack: Move by Move Korchnoi: Move by Move The Alekhine Defence: Move by Move The Trompowsky Attack: Move by Move Carlsen: Move by Move The Classical French: Move by Move Larsen: Move by Move 1...b6: Move by Move Bird’s Opening: Move by Move The Petroff: Move by Move Fischer: Move by Move Anti-Sicilians: Move by Move Contents About the Author 3 Bibliography 5 Introduction 7 1 The Early Years 21 2 World Champion and 1960-1970 153 3 The Later Years 299 Index of Openings 394 Index of Complete Games 395 Introduction Things are not what they appear to be; nor are they otherwise. – Surangama Sutra The nature of miracles is they contradict our understanding of what we consider ‘truth’. Perhaps the miracle itself is a truth which our minds are too limited to comprehend. Mik- hail Nekhemevich Tal was just such a miracle worker of the chess board. -

Glossary of Chess

Glossary of chess See also: Glossary of chess problems, Index of chess • X articles and Outline of chess • This page explains commonly used terms in chess in al- • Z phabetical order. Some of these have their own pages, • References like fork and pin. For a list of unorthodox chess pieces, see Fairy chess piece; for a list of terms specific to chess problems, see Glossary of chess problems; for a list of chess-related games, see Chess variants. 1 A Contents : absolute pin A pin against the king is called absolute since the pinned piece cannot legally move (as mov- ing it would expose the king to check). Cf. relative • A pin. • B active 1. Describes a piece that controls a number of • C squares, or a piece that has a number of squares available for its next move. • D 2. An “active defense” is a defense employing threat(s) • E or counterattack(s). Antonym: passive. • F • G • H • I • J • K • L • M • N • O • P Envelope used for the adjournment of a match game Efim Geller • Q vs. Bent Larsen, Copenhagen 1966 • R adjournment Suspension of a chess game with the in- • S tention to finish it later. It was once very common in high-level competition, often occurring soon af- • T ter the first time control, but the practice has been • U abandoned due to the advent of computer analysis. See sealed move. • V adjudication Decision by a strong chess player (the ad- • W judicator) on the outcome of an unfinished game. 1 2 2 B This practice is now uncommon in over-the-board are often pawn moves; since pawns cannot move events, but does happen in online chess when one backwards to return to squares they have left, their player refuses to continue after an adjournment. -

The Chess Endgame Studies of Richard Réti : Introduction

To the memory of David Hooper and Ken Whyld, in the belief that this is something they would have liked to see The Chess Endgame Studies of Richard Réti : Introduction John Beasley, 14 January 2012, latest revision 12 November Richard Réti (1889-1929) has always been one of my chess heroes, and ever since I first saw the stunning pawn study with which his name is indissolubly linked I have taken a particular delight in his endgame studies. I first met them in Golombek’s 1954 book of his best games, where fifteen of them appear, and I have always looked out for them since. Nearly all are in Sutherland and Lommer’s 1234 modern endgame studies and rather more than all are in Harold van der Heijden’s “Endgame study database IV” (more about this later), but the standard collection has always been Artur Mandler’s Richard Réti : Sämtliche Studien of 1931. There was a Spanish edition of this in 1983 and I used to have a copy, but while I was looking after the library of the British Chess Problem Society I lodged it there on loan, and it was the one book I could not find when I came to reclaim my loans before the library moved elsewhere. Fortunately Jan Kalendovský had included all the studies in his 1989 book Richard Réti, šachový myslitel, and on looking at this again recently it occurred to me that a complete presentation of Réti’s studies in English would be a job well worth doing. According to Kalendovský, Mandler’s book was translated into a range of languages including English, but I have never seen an English edition and the British Library appears not to possess one. -

Cyrus Lakdawala Tactical Training

CYRUS LAKDAWALA TACTICAL TRAINING www.everymanchess.com About the Author is an International Master, a former National Open and American Open Cyrus Lakdawala Champion, and a six-time State Champion. He has been teaching chess for over 30 years, and coaches some of the top junior players in the U.S. Also by the Author: 1...b6: Move by Move 1...d6: Move by Move A Ferocious Opening Repertoire Anti-Sicilians: Move by Move Bird’s Opening: Move by Move Botvinnik: Move by Move Capablanca: Move by Move Carlsen: Move by Move Caruana: Move by Move First Steps: the Modern Fischer: Move by Move Korchnoi: Move by Move Kramnik: Move by Move Larsen: Move by Move Opening Repertoire: ...c6 Opening Repertoire: Modern Defence Opening Repertoire: The Sveshnikov Petroff Defence: Move by Move Play the London System The Alekhine Defence: Move by Move The Caro-Kann: Move by Move The Classical French: Move by Move The Colle: Move by Move The Four Knights: Move by Move The Modern Defence: Move by Move The Nimzo-Larsen Attack: Move by Move The Scandinavian: Move by Move The Slav: Move by Move The Trompowsky Attack: Move by Move Contents About the Author 3 Bibliography 6 Introduction 7 1 Various Mating Patterns 13 2 Shorter Mates 48 3 Longer Mates 99 4 Annihilation of Defensive Barrier/Obliteration/Demolition of Structure 161 5 Clearance/Line Opening 181 6 Decoy/Attraction/Removal of the Guard 194 7 Defensive Combinations 213 8 Deflection 226 9 Desperado 234 10 Discovered Attack 244 11 Double Attack 259 12 Drawing Combinations 270 13 Fortress 279 14 Greek Gift Sacrifice -

|||GET||| the Immortal Game a History of Chess 1St Edition

THE IMMORTAL GAME A HISTORY OF CHESS 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE David Shenk | 9781400034086 | | | | | The Immortal Game Final position after Jan 26, Ciro rated it it was amazing. A surprising, charming, and ever-fascinating history of the seemingly simple game that has had a profound effect on societies the world over. Full of wonderful anecdotes,this book is a strong move,wonderful reading! It made me want to play some The Immortal Game A History of Chess 1st edition chess for the first time in years, and I can't think of a better endorsement. I had access to books and willing adversaries. InBill Hartston called the game an achievement "perhaps unparalleled in chess literature". Apr 07, Rebecca Jones rated it really liked it. Why has one game, alone among the thousands of games invented and played throughout human history, not only survived but thrived within every culture it has touched? Her loneliness and drive to make it through Related Articles. The Upright Thinkers. On their honeymoon he spent the entire week studying chess problems. Halfway through this book I knew I was going t Yes The Immortal Game A History of Chess 1st edition book gets into the History of Chess but really it is about a specific game played on June 21, between Adolf Anderssen and Lionel Kieseritzky, two world chess champion candidates playing a tune-up match in a pub in London. Notes Chaturanga first time no randomizer diceThe Immortal Game A History of Chess 1st edition with new numeral system. Chess is the simply the most important game in the history of the world. -

![Chess Fortresses, a Causal Test for State of the Art Symbolic[Neuro] Architectures](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9199/chess-fortresses-a-causal-test-for-state-of-the-art-symbolic-neuro-architectures-3419199.webp)

Chess Fortresses, a Causal Test for State of the Art Symbolic[Neuro] Architectures

Chess fortresses, a causal test for state of the art Symbolic[Neuro] architectures Hedinn Steingrimsson Electrical and Computer Engineering Rice University Houston, TX 77005 [email protected] Abstract—The AI community’s growing interest in causality (which can only move on white squares) does not contribute to is motivating the need for benchmarks that test the limits of battling the key g5 square (which is on a black square), which is neural network based probabilistic reasoning and state of the art sufficiently protected by the white pieces. These characteristics search algorithms. In this paper we present such a benchmark, chess fortresses. To make the benchmarking task as challenging beat the laws of probabilistic reasoning, where extra material as possible, we compile a test set of positions in which the typically means increased chances of winning the game. This defender has a unique best move for entering a fortress defense feature makes the new benchmark especially challenging for formation. The defense formation can be invariant to adding a neural based architectures. certain type of chess piece to the attacking side thereby defying the laws of probabilistic reasoning. The new dataset enables Our goal in this paper is to provide a new benchmark of efficient testing of move prediction since every experiment yields logical nature - aimed at being challenging or a hard class - a conclusive outcome, which is a significant improvement over which modern architectures can be measured against. This new traditional methods. We carry out extensive, large scale tests dataset is provided in the Supplement 1. Exploring hard classes of the convolutional neural networks of Leela Chess Zero [1], has proven to be fruitful ground for fundamental architectural an open source chess engine built on the same principles as AlphaZero (AZ), which has passed AZ in chess playing ability improvements in the past as shown by Olga Russakovsky’s according to many rating lists. -

Endgame Corner the Rook Moves the Same As in Western Chess

Chinese Chess This month I want to make a comparison between Chinese chess and Western chess with a focus on endgame fortresses, but first an explanation of Chinese chess seems to be in order. The Rules Chinese chess is played on the intersections of a 9x10 board. The two sides are called red and black. Each side has a king (general), two rooks (chariots), two cannons (or catapults), two knights (horses), two elephants (ministers or bishops), two mandarins (guards or assistants) and five pawns (soldiers). In the middle of the board there is a river. The pieces that can cross the river (rooks, cannons, knights and pawns) are called attacking pieces. The king and the guards are confined to the palace, the 3x3 square around the king (d1-d3- f3-f1 for red). Endgame Corner The rook moves the same as in Western chess. The cannons move like a rook, but to Karsten Müller capture it needs a frame (any other piece) to jump over in order to capture the enemy piece behind the frame. This is similar to a cannon ball fired above the frame, which obliterates the enemy by landing on it. The knights move one point vertically or horizontally and then one point diagonally away from its former position, but they cannot jump. For instance, a knight on b1 can move to a3, c3 and d2, but any piece on b2 would block the access to a3 and c3 and any piece on c1 blocks d2. So with pieces on b2 and c1, a knight on b1 cannot move at all. -

How to Be Lucky in Chess

HOW TO BE Somt pIayIta eeem to have an InexheuIIIbIetuppIy of dliliboard luck. No matI8r theywhat tn:dIII fh:Ilh8rnIeIves In, they somehow IIWIIQIIto 1IOIIIPe. Among wodcI c:hampIorB. 1.aIker.'nil end KMpanw1ft tamed tor PI8IfnG ., the aby8I bullOInehow making an It Ie their opponenII who fill. LUCKY ___ 10.... __ -_---"" __ cheeI. 10 make Iht moet oIlhaIr abMle8. UnIkemoll prIVku ....... on cheIa�, this II no heev,welghltheor8IIcaI . trMIIat but,...,.. IN pradIcII guide In how to MeopponenIIlnIo error- II'ld IhuI cntUI whllllI often -",*" DMd UIIoIr 18 an experienced cheu pII)W Ind wrIIBr. He twice won lie chanlplo ......'p cf the Welt of England and was � on four 0CCIII0I• . In CHESS 2000. he was County Champion 01 Norfolk. In alUCCB altai CMMH' ... .... _ ......... .. ... ___ ... ..... _ond __ _ ...... _by-- In encouraging your opponents to seH-destructl KMlI.eIIoIr II • nIdr8d I8chnlcalIIIuItraIor and. ....11nCe cartoon" whoM David LeMoir work hal appeared In 8 wtcIe IW'IgIt of magazIna and 0IhIr � Ofw ... __ a.ntrt�.tII:I1r.dI: ..... .......aI a-......, 'l1li. ... u.dIJet.._ -- -- n. ......a.. ..... '_ ........ ......,.a-n , ;11111 .... '111m__ .... - *" AnMd:"... a-.01ce -- .... -- -- ........_ .. a-............ .., a..TNInIna_....... O ,11• -- -"" __"ten, UIIIm ........ ---=.....".o.ndIwOM a.. CIIoIID': OrJIIhnHImOM I!dbIII '*-':.... -...n FU �...... .. � ..... ...� .. #I: -- '" ".0... ..." LGIIdonW14 G.If,!ngIInd. Or...cl.. ..... 1D:100117.D01t--...-.- �. ...,& .. "'- How to Be Lucky in Chess David LeMoir Illustrations by Ken LeMoir �I�lBIITI First published in the UK by Gambit Publications Ltd 2001 Contents Copyright © David LeMoir 2001 Illustrations © Ken LeMoir 2001 The right of David LeMoir to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accor dance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

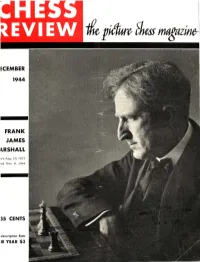

Ecember Frank James Arshall

, ECEMBER 1944 FRANK JAMES ARSHALL orn A 11,g. 10, 1877 'it" N u". 9, 1944 35 CENTS ubstripli on Rate IE YEAR $3 HARE THE J OYS of chess with yom' friends and relatives ! Give them the opportunity to S leaI'll the Royal Game and enjoy countl ess hours of happiness over the checkcl'ed board ! In troduce chess to others a nd help to spread intel'est in the Game of Kings! lIow ? By presenting your friends with Chl'ist mas Gift su bsc riptions to CHE SS REVIEW! E ven if Lhey know nothing about chess, this special ,s ub scription will bl'i ng them a complete course of in struction. Wilh- ench gift subscription we will include, free of charge, reprints of all the previous installments of " Let's Play Chess"- ou l' Picture Guidu to Chess-so that yOll!' friends ca n start this fascinating course from the beginning and learn how to play chess with the aid of this pic torial, self-teaching guide! This is something yOli /.: 1/.010 your friends will appr eciate, Just before Christmas they will re ceive the Decembel- issue of CHESS REVIEW and :.\]] the r epl"i nts of t he P icture Guide- a re"l Christmas package_ Then, as t hey receive the s ubsequcnt issues of CHESS RE VIEW , they will be reminded of you again a nd again_ As they fol low the installments of t he course and r ead all the other features of CHESS REVIEW t hey will be grateful to you fol' having introduced t hem to t he greatest game in the world_ You will have brought CHESS REVIEW THE PICTURE CHESS MAGAZ IJf[ them a li fet ime of pleas lll-e and happiness ! To each of your friends \\"e will also send the unique Chl'istmas Card reproduced Oil this page_ This c<lrd .announces your gift, tells YOLlI- friend t hat CHF;SS REVIEW is coming to him for onc, two 01' thl-ee years wi t h your best wishes and g't'eetings_ The cH.