Analysis of Sacrococcygeal Morphology in Koreans Using

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prevalence and Incidence of Osteoporosis and Osteoporotic Vertebral Fracture in Korea Nationwide Epidemiological Study Focusing on Differences in Socioeconomic Status

SPINE Volume 41, Number 4, pp 328–336 ß 2016 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved EPIDEMIOLOGY Prevalence and Incidence of Osteoporosis and Osteoporotic Vertebral Fracture in Korea Nationwide Epidemiological Study Focusing on Differences in Socioeconomic Status Sung Bae Park, MD, PhD,Ã Jayeun Kim, PhD,y Je Hoon Jeong, MD,z Jung-Kil Lee, MD, PhD,§ Dong Kyu Chin, MD, PhD,{ Chun Kee Chung, MD, PhD,jj Sang Hyung Lee, MD, PhD,Ã and Jin Yong Lee, MD, PhD# Results. In 2012, the standardized prevalence of OP in the Study Design. A cross-national study. NHI and MA groups was 3968 and 6927 per 100,000, Objective. To determine the prevalence and incidence of respectively (odds ratio, 3.83). The standardized incidence of osteoporosis (OP) and osteoporotic vertebral fracture (OVF) in OP in the MA group was significantly higher than in the NHI Korea and to investigate if socioeconomic status has an effect. group in 2011 and 2012 (odds ratios, 2.34 and 2.19, respect- Summary of Background Data. As life expectancy increases, ively). In addition, the standardized incidence of OVF in the MA OP and related fragility fractures are also increasing. This group in 2011 and 2012 was 408 and 389 per 100,000, presents a serious challenge, not only for health authorities but respectively, and the incidence in the MA group was signifi- also for individuals, their families, and society overall. Determin- cantly higher than in the NHI group (odds ratios, 4.13 and 4.12, ing the prevalence and incidence of OP and related fragility respectively; P < 0.001). -

Fractures of the Craniovertebral Junction Associated with Other Fractures of the Spine: Overlooked Entity?

775 Fractures of the Craniovertebral Junction Associated with Other Fractures of the Spine: Overlooked Entity? Charles Lee 1 In a review of 155 craniovertebral fractures (occiput-C1-C2), 40 of these had asso Lee F. Rogers2 ciated fractures and/or dislocations or subluxations elsewhere in the spine. This rather John H. Woodring1 common occurrence, one of four, has not been emphasized in the recent literature, Steven J. Goldstein1 indicating that the radiologic examination should not stop after the craniovertebral Kwang S. Kim 2 fracture is identified. Furthermore, in 13 patients, neurologic deficits were encountered that in all instances were from associated lower-level fracture. From this experience it was believed that a minimum of anteroposterior and lateral views of the entire spine should be obtained in patients in whom a craniovertebral fracture is found, especially if neurologic deficits are present. The other sites of injury were in the lower cervical spine in 17 patients, in the thoracic spine in five, in the lumbar spine in two, and in the sacrococcygeal spine in two patients. Eight patients had three or more levels of fracture. Craniovertebral fractures are a unique category of spinal fractures involving the occipital bone, atlas, and axis. In 1939 Plaut [1] reported the largest series of atlas fractures, 99 cases, of which 59 involved both the atlas and the other sites in the cervical spine. Thirty-three of these 59 were confined just to the C1 and C2 levels, and the other cases involved the atlas and the rest of the lower cervical spine. Since that time there have been other reports about craniovertebral fractures occurring in combination with other fractures of the spine [2-8], but none have stressed how often this combination occurs . -

COCCYGEAL FRACTURES in ADULTS AS a RESULT of FALL on FROZEN SNOW DURING Bashir Ahmed Mir Et Al WINTER in KASHMIR

COCCYGEAL FRACTURES IN ADULTS AS A RESULT OF FALL ON FROZEN SNOW DURING Bashir Ahmed Mir et al WINTER IN KASHMIR COCCYGEAL FRACTURES IN ADULTS AS A RESULT OF FALL ON FROZEN SNOW DURING WINTER IN KASHMIR IJCRR Bashir Ahmed Mir, Muzamil Ahmad Baba, M.A. Halwai, Adil Bashir Shikari, Vol 05 issue 16 Maajid Shabeer, Naila Nazir Section: Healthcare Category: Research Received on: 14/07/13 Department of Orthopaedics, Govt. Medical College Srinagar, J&K, India Revised on: 03/08/13 Accepted on: 26/08/13 E-mail of Corresponding Author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Background There is not much literature available on coccygeal fractures, only a few case reports. We present a first series of 15 cases of coccygeal fractures in adults as a result of similar mode of trauma due to fall on frozen snow during the winter months in the valley of Kashmir. Material and Methods: The study included patients with coccygeal fractures that occurred as a result of direct fall due to slip on ice during the winter months, December to February in the valley of Kashmir. Study was done over a period of 5 years (2007 to 2012) and included a total of 15 patients. Results: 15 cases of coccygeal fractures with an age group of 48 to 72 (average 65 years), 12 females and 3 males is presented. All patients were managed conservatively with uneventful recovery. Conclusion: Our study revealed coccygeal fractures mostly occur in elderly age group with underlying osteoporosis. Although most cases can be managed conservatively with uneventful recovery, measures should be taken to avoid fall related trauma in winters especially in older age group. -

Campo Image Bank.Pdf

CAMPO MEDICAL IMAGING FOR THE HEALTH CARE PROVIDER MEDICAL IMAGING FOR THE HEALTH CARE PROVIDER MEDICAL IMAGING FOR THE HEALTH Image Bank PRACTICAL RADIOGRAPH INTERPRETATION THERESA M. CAMPO, DNP, FNP-C, ENP-BC, FAANP The only text to integrate the basics of radiology, characteristics and differences MEDICAL of testing modalities, and interpretation skills his unique book fi lls a void in radiology interpretation texts by encompassing the foundational T tools and concepts of the full range of medical imaging, including radiology, the basics of interpretation of plain radiographs, comparison with other testing modalities, the rationale for se- lecting the fi rst diagnostic step, and exploration and interpretation of chest, abdomen, extremity, and spinal radiographs. A concise, easy-to-use reference, it includes written descriptions enhanced IMAGING with fi gures, tables, and actual patient fi lms to demonstrate concepts, and discusses—in easily accessible language—differences in testing modalities. The text also features a step-by-step guide to the interpretation of radiographs. This resource describes and compares available diagnostic modalities, including plain radiograph, CT scan, nuclear imaging, MRI, and ultrasound. It discusses pediatric considerations and includes separate chapters for the chest, abdomen, upper and lower extremities, and the cervical, thoracic, FOR THE and lumbar spine. The book will be an asset to nurse practitioners and physician assistants working in all emergency, urgent, intensive, and primary care settings. It will also benefi t medical students and graduate students in acute care, family, adult/gerontology, and emergency nurse practitioner programs, as well as emergency/trauma clinical nurse specialists, and hospitalists and intensivist nurse practitioners. -

Download Full-Text

® Clinical Case Report Medicine OPEN Laser acupuncture for refractory coccydynia after traumatic coccyx fracture A case report Chien-Hung Lin, MDa, Szu-Ying Wu, MDa,b, Wen-Long Hu, MD, MSa,c,d, Chia-Hung Hung, MDe, ∗ Yu-Chiang Hung, MD, PhDa,f, Chun-En Aurea Kuo, MD, MSa,g, Abstract Rationale: Coccyx fracture is an injury usually caused by trauma. In most cases, the fractures recover after conservative therapy. For refractory cases that exhibit coccydynia after more than 2 months of conservative treatment, coccygectomy is indicated. However, limited information about the efficacy of this procedure is available, and it is known to have a high complication rate. As such, other therapeutic approaches are needed. Here, we report our experience using another conservative treatment option, low-level laser therapy, to successfully reduce refractory coccydynia in a patient with coccyx fracture. Patient concerns: A 23-year-old woman had refractory coccydynia and increased pain after a traffic accident-induced coccyx fracture. Diagnoses: Initially, the patient reported transient improvement after conservative treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. However, the pain increased in severity (numerical rating scale score of 8) soon after she resumed work in her office, and progressed in the following 2 months. Surgical intervention was suggested owing to the prolonged coccydynia following the failure of conservative treatment and difficulties in performing daily life activities. However, she sought other conservative therapy options, because she was concerned about the risks associated with the coccygectomy surgery. Interventions: The patient received low-level laser therapy once a week, for 24 weeks. Outcomes: After 11 weeks of treatment, the patient reported significant improvements in her symptoms; her pain was reduced to a numerical rating scale score of 2 and bone healing was noted on radiographs. -

Low Back Pain Anatomy of the Pubic Symphysis Sacroiliac Joint Articular

Sacroiliac Joint dysfunction, Coccydinia, and Dynamic stability of the lumbo-pelvic region Low back pain altered Pelvic Floor function: is there a link? Stability of inter-segmental lumbar motion is reliant on appropriate control of muscle activation by the central nervous system Delayed recruitment of Increased activity of deep local muscles superficial global muscles -Lumbar multifidus -Transversus abdominus -EO / IO -Pelvic floor -Erector spinae -iliopsoas -biceps femoris Presented by TrA, lower transverse fibres Increase segmental stiffness Compensation due to Dr Barbara Hungerford PhD B.App.Sci (Physio) Internal oblique (OI), deep Co-contract and limit inter-segmental lumbar multifidus & pelvic motion in lumbar spine decreased segmental stability Director : Sydney Spine & Pelvis Centre, Australia floor activate prior to motion : Advanced Manual Therapy Associates (Hodges & Richardson, 1997; Moseley et al, 2002; O’Sullivan et al, 1997) Hides, 94; Hodges & Richardson, 96; Hodges 2003; Radebold 2000 Lumbo-pelvic Stability and optimal load transfer Anatomy of the pubic symphysis Sacroiliac joint articular surface Lumbo-pelvic region is always interacting with * Fibrocartilaginous gravity joint The SIJ is classified as a * interposed by *diarthroidal synovial joint fibrocartilaginous 65% body weight *hyaline articular cartilage transferred across L5/ disc *synovial capsule S1 in standing * most stable joint in pelvis *6 degrees of freedom Pelvis is the stable platform or hub of the skeleton Developmental changes of the SIJ articular Factors -

Improved Bone Healing After Oral Application of Specific Bioactive Collagen Peptides Hans-Christoph Knefeli1, Michael Mueller-Autz2

Nutrafoods (2018) 17:185-188 ORIGINAL RESEARCH DOI 10.17470/NF-018-1022-4 Received: October 25, 2018 Accepted: November 6, 2018 Improved bone healing after oral application of specific bioactive collagen peptides Hans-Christoph Knefeli1, Michael Mueller-Autz2 Correspondence to: Hans-Christoph Knefeli - [email protected] The complete and undisturbed healing of bone fractures is a key priority for surgeons and patients, so intensive efforts are made to improve bone healing with a variety of approaches. Oral therapies with Keywords ABSTRACT collagen peptides are a relatively new therapeutic approach. Bioactive collagen peptides In this observational study, the impact of collagen peptides on bone healing was investigated in a Nutritional supplement group of 28 (14 verum/14 placebo) patients of both genders with different fracture locations. Some Bone fracture patients underwent surgery, while others were treated conservatively. The patients who received bioac- Bone healing tive collagen peptide treatment (FORTIBONE®) had a clearly better outcome regarding bone healing than the placebo group, half of whom showed suboptimal or bad results. No side effects or intolerance to the product were reported. The results of this investigation confirm the positive impact of collagen peptides on bone healing. The data suggest that FORTIBONE® can be used to improve fracture healing, even in cases where a normal outcome is expected, and to achieve faster healing. Introduction has also been examined in a validated model that showed collagen peptides accumulate in the target tissue [4, 5]. Ex- Complete and undisturbed bone healing in a timely fashion perimental studies on primary human osteoblasts have dem- is a key priority for surgeons and patients. -

Clinical Evolution of Sacral Stress Fractures: Ann Rheum Dis: First Published As 10.1136/Ard.52.7.545 on 1 July 1993

Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 1993; 52: 545-547 545 Clinical evolution of sacral stress fractures: Ann Rheum Dis: first published as 10.1136/ard.52.7.545 on 1 July 1993. Downloaded from influence of additional pelvic fractures P Peris, N Guafiabens, F Pons, R Herranz, A Monegal, X Suris, J Mufioz-Gomez Abstract Patients and methods Objectives-To evaluate the clinical Over a period of 34 months (March 1989 to evolution of sacral stress fractures in January 1992), 14 patients (12 women, two relation to the scintigraphic pattern and men) were diagnosed as having sacral the presence of additional pelvic fractures. The average age was 65 years (range fractures. 48-80 years). Their clinical records were Methods-This was a retrospective study reviewed to determine their presenting of 14 patients with sacral fractures. symptoms, the risk factors for fracture, and the Results-Six patients had additional clinical evolution. Special attention was paid to pelvic fractures. Four bone scintigraphic the chronological course of clinical symptoms. patterns were found. The resolution of Sacral plain film radiography and bone symptoms was longer in patients with scintigraphy were performed on all patients associated pelvic fractures (30 weeks v and, in five, computed tomography (CT) was three weeks). No relation was found also used. Lumbar bone mineral density between the bone scintigraphic pattern (BMD) was measured by dual photon and the time ofevolution. absortiometry (Lunar-DP3) in 11 patients. Conclusion-Associated pelvic fractures The diagnosis of sacral fracture was delay the resolution of symptoms in established on the basis of the presence of patients with sacral fractures, regardless compatible clinical data confirmed by one or ofscintigraphic pattern. -

Before the Arkansas Workers' Compensation

BEFORE THE ARKANSAS WORKERS’ COMPENSATION COMMISSION CLAIM NO. F402542 DEBBIE A. ROGERS, EMPLOYEE CLAIMANT WAL-MART STORES, INC., EMPLOYER RESPONDENT CLAIMS MANAGEMENT, INC., INSURANCE CARRIER/TPA RESPONDENT OPINION FILED APRIL 12, 2006 Hearing before Chief Administrative Law Judge David Greenbaum on March 10, 2006, at Jonesboro, Craighead County, Arkansas. Claimant appeared, pro se. Respondents represented by Ms. Susan M. Fowler, Attorney-at-Law, Little Rock, Arkansas. STATEMENT OF THE CASE A hearing was conducted March 10, 2006, to determine whether the claimant was entitled to additional workers’ compensation benefits. A prehearing conference was conducted in this claim on February 1, 2006, and a Prehearing Order was filed on said date. At the hearing, the parties announced that the stipulations, issues, as well as their respective contentions were properly set out in the Prehearing Order. In addition, at the hearing, based upon the undisputed testimony of Robin Roby, the employer’s personnel manager, it was determined that the claimant earned $10.61 per hour under a contract of hire for thirty-five (35) hours, and that her average weekly wage on March 7, 2004, was $374.97. (Tr.8, 67-68) It was undisputed that the employment relationship existed between the parties at all relevant times, including March 7, 2004; that the claimant earned sufficient wages to entitle her to compensation rates of $250.00 per week for temporary total disability and $188.00 per week for permanent partial disability; that the claimant sustained a compensable injury to her left forearm as the result of a specific incident identifiable in time and place of occurrence when she fell off a ladder at work on said date; that respondents paid various medical and related expenses allegedly for the left forearm injury while controverting any additional injuries. -

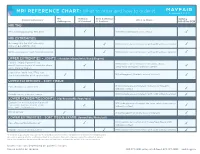

MRI REFERENCE CHART: What to Order and How to Order It

MRI REFERENCE CHART: What to order and how to order it MR Without With & Without Clinical Indications What to Order Optima Arthrogram IV Contrast IV Contrast MR450w GEM MRI TMJ TMJ, clicking/popping, TMJ joint MRI TMJ bilateral without contrast MRI EXTREMITIES Osteomyelitis for ANY extremity; MRI (indicate area of interest) with AND without contrast spine or general infection Soft tissue mass of ANY extremity or joint MRI (indicate area of interest) with AND without contrast UPPER EXTREMITIES – JOINTS: (shoulder/elbow/wrist/hand/fingers) Evaluate injury, ligament tear, MRI (indicate area of interest: shoulder, elbow, occult fracture or pain of shoulder, elbow, wrist, hand or fingers) without contrast wrist, hand or fingers Slap lesion, labral tear, TFCC tear, MR arthrogram* (indicate area of interest) shoulder instability, post-op shoulder UPPER EXTREMITIES – SOFT TISSUE Pain of humerus or forearm MRI (indicate area of interest: humerus or forearm) without contrast Palpable mass, neuroma, tumor MRI (indicate area of interest) with AND without contrast LOWER EXTREMITIES/JOINTS: (hip/knee/ankle/foot/toes) Evaluate for meniscal injury, ligament MRI (indicate area of interest: hip, knee, ankle, foot or toes) tear, occult fracture or pain of hip, without contrast knee, ankle, foot or toes Hip labral tear MR arthrogram* (indicate area of interest) LOWER EXTREMITIES – SOFT TISSUE EXAMS: (femur/tibia/fibula/calf) Pain of femur/tibia/fibula/calf MRI (indicate area of interest: femur/tibia/fibula/calf) without contrast Palpable mass, neuroma, tumor MRI (indicate area of interest) with AND without contrast *If Contrast is specifically requested by the practitioner/referrer, this contrast will be administered intraarticularly (a needle is guided into the joint and contrast is injected into the joint.) This will require the patient ot have a fluroscopy study first during which the injection will take place, followed by an MRI of the area in question. -

The Epidemiology of Fracture-Related Infections in Germany

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The epidemiology of fracture‑related infections in Germany Nike Walter1,2,3, Markus Rupp1,3*, Siegmund Lang1 & Volker Alt1 The epidemiology of fracture‑related infection (FRI) is unknown, which makes it difcult to estimate future demands and evaluate progress in infection prevention. Therefore, we aimed to determine the nationwide burden’s development over the last decade as a function of age group and gender. FRI prevalence as a function of age group and gender was quantifed based on annual ICD‑10 diagnosis codes from German medical institutions between 2008 through 2018, provided by the Federal Statistical Ofce of Germany (Destatis). The prevalence of FRI increased by 0.28 from 8.4 cases per 100,000 inhabitants to 10.7 cases per 100,000 inhabitants between 2008 and 2018. The proportion of fractures resulting in FRI increased from 1.05 to 1.23%. Gender distribution was equal. Patients aged 60–69 years and 70–79 years comprised the largest internal proportion with 20.2% and 20.7%, respectively, whereby prevalence increased with age group. A trend towards more diagnoses in older patients was observed with a growth rate of 0.63 for patients older than 90 years. Increasing rates of fracture‑related infection especially in older patients indicate an upcoming challenge for stakeholders in health care systems. Newly emerging treatment strategies, prevention methods and interdisciplinary approaches are strongly required. In trauma surgery, reduction and internal fxation is applied to restore skeletal integrity. One of the major com- plications afer fracture fxation utilizing metallic fracture fxation devices, is implant related infection, which in general requires surgical treatment Depending on several factors, at least one, but ofen two or even multiple staged surgeries are needed for eradication of infection and fnally bony consolidation1. -

Fracture Outcome Details (Form 123, Cad Ppts) Through Extension 1

Fracture Outcome Details (Form 123, CaD ppts) through Extension 1 File Name Population Data Collected 1 row per Rows outc_fracture_cad_dbgap_rel4.dat WHI dbGaP Cohort: Main, Ext1 Outcome Form 2,548 CaD This file has one row for every form 123 recording outcome(s). A participant may have more than one of these forms. Only the first occurrence of each outcome is counted, e.g. Limiting the file to rows where BKANKLE=1 will find a single row for each participant with an ankle fracture outcome. *SUBJID WHI dbGaP Subject ID Col#1 ASCSOURCE Ascertainment Source Col#2 Value Description N % 1 Local Form 123 2,077 81.5 2 Central Form 123 471 18.5 *BKANKLE Ankle Fracture Col#3 Value Description N % 1 Yes 296 11.6 Missing 2,252 88.4 Usage Notes: Ankle Fracture was adjudicated during the core WHI study. It was adjudicated at all clinics for CT participants, but only adjudicated at the bone density clinics for OS participants. Ankle Fracture is not counted if pathologic. *BKCARPAL Carpal Fracture Col#4 Carpal bones in wrist Value Description N % 1 Yes 42 1.6 Missing 2,506 98.4 Usage Notes: Carpal Fracture was adjudicated during the core WHI study. It was adjudicated at all clinics for CT participants, but only adjudicated at the bone density clinics for OS participants. Carpal Fracture is not counted if pathologic. *BKCLAVICLE Clavical Fracture Col#5 Value Description N % 1 Yes 29 1.1 Missing 2,519 98.9 Usage Notes: Clavical Fracture was adjudicated during the core WHI study.