Wuvulu Grammar and Vocabulary (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Archaeology of Lapita Dispersal in Oceania

The archaeology of Lapita dispersal in Oceania pers from the Fourth Lapita Conference, June 2000, Canberra, Australia / Terra Australis reports the results of archaeological and related research within the south and east of Asia, though mainly Australia, New Guinea and Island Melanesia — lands that remained terra australis incognita to generations of prehistorians. Its subject is the settlement of the diverse environments in this isolated quarter of the globe by peoples who have maintained their discrete and traditional ways of life into the recent recorded or remembered past and at times into the observable present. Since the beginning of the series, the basic colour on the spine and cover has distinguished the regional distribution of topics, as follows: ochre for Australia, green for New Guinea, red for Southeast Asia and blue for the Pacific islands. From 2001, issues with a gold spine will include conference proceedings, edited papers, and monographs which in topic or desired format do not fit easily within the original arrangements. All volumes are numbered within the same series. List of volumes in Terra Australis Volume 1: Burrill Lake and Currarong: coastal sites in southern New South Wales. R.J. Lampert (1971) Volume 2: Ol Tumbuna: archaeological excavations in the eastern central Highlands, Papua New Guinea. J.P. White (1972) Volume 3: New Guinea Stone Age Trade: the geography and ecology of traffic in the interior. I. Hughes (1977) Volume 4: Recent Prehistory in Southeast Papua. B. Egloff (1979) Volume 5: The Great Kartan Mystery. R. Lampert (1981) Volume 6: Early Man in North Queensland: art and archeaology in the Laura area. -

Civil Aviation Development Investment Program (Tranche 3)

Resettlement Due Diligence Reports Project Number: 43141-044 June 2016 PNG: Multitranche Financing Facility - Civil Aviation Development Investment Program (Tranche 3) Prepared by National Airports Corporation for the Asian Development Bank. This resettlement due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Table of Contents B. Resettlement Due Diligence Report 1. Madang Airport Due Diligence Report 2. Mendi Airport Due Diligence Report 3. Momote Airport Due Diligence Report 4. Mt. Hagen Due Diligence Report 5. Vanimo Airport Due Diligence Report 6. Wewak Airport Due Diligence Report 4. Madang Airport Due Diligence Report. I. OUTLINE FOR MADANG AIRPORT DUE DILIGENCE REPORT 1. The is a Due Diligent Report (DDR) that reviews the Pavement Strengthening Upgrading, & Associated Works proposed for the Madang Airport in Madang Province (MP). It presents social safeguard aspects/social impacts assessment of the proposed works and mitigation measures. II. BACKGROUND INFORMATION 2. Madang Airport is situated at 5° 12 30 S, 145° 47 0 E in Madang and is about 5km from Madang Town, Provincial Headquarters of Madang Province where banks, post office, business houses, hotels and guest houses are located. -

Health&Medicalinfoupdate8/10/2017 Page 1 HEALTH and MEDICAL

HEALTH AND MEDICAL INFORMATION The American Embassy assumes no responsibility for the professional ability or integrity of the persons, centers, or hospitals appearing on this list. The names of doctors are listed in alphabetical, specialty and regional order. The order in which this information appears has no other significance. Routine care is generally available from general practitioners or family practice professionals. Care from specialists is by referral only, which means you first visit the general practitioner before seeing the specialist. Most specialists have private offices (called “surgeries” or “clinic”), as well as consulting and treatment rooms located in Medical Centers attached to the main teaching hospitals. Residential areas are served by a large number of general practitioners who can take care of most general illnesses The U.S Government assumes no responsibility for payment of medical expenses for private individuals. The Social Security Medicare Program does not provide coverage for hospital or medical outside the U.S.A. For further information please see our information sheet entitled “Medical Information for American Traveling Abroad.” IMPORTANT EMERGENCY NUMBERS AMBULANCE/EMERGENCY SERVICES (National Capital District only) Police: 112 / (675) 324-4200 Fire: 110 St John Ambulance: 111 Life-line: 326-0011 / 326-1680 Mental Health Services: 301-3694 HIV/AIDS info: 323-6161 MEDEVAC Niugini Air Rescue Tel (675) 323-2033 Fax (675) 323-5244 Airport (675) 323-4700; A/H Mobile (675) 683-0305 Toll free: 0561293722468 - 24hrs Medevac Pacific Services: Tel (675) 323-5626; 325-6633 Mobile (675) 683-8767 PNG Wide Toll free: 1801 911 / 76835227 – 24hrs Health&MedicalInfoupdate8/10/2017 Page 1 AMR Air Ambulance 8001 South InterPort Blvd Ste. -

PNG: Building Resilience to Climate Change in Papua New Guinea

Environmental Assessment and Review Framework September 2015 PNG: Building Resilience to Climate Change in Papua New Guinea This environmental assessment and review framework is a document of the borrower/recipient. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Project information, including draft and final documents, will be made available for public review and comment as per ADB Public Communications Policy 2011. The environmental assessment and review framework will be uploaded to ADB website and will be disclosed locally. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................... ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................. ii 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 1 A. BACKGROUND ..................................................................................................................................... -

The Relationships of the Starlings (Sturnidae: Sturnini) and the Mockingbirds (Sturnidae: Mimini)

THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE STARLINGS (STURNIDAE: STURNINI) AND THE MOCKINGBIRDS (STURNIDAE: MIMINI) CHARLESG. SIBLEYAND JON E. AHLQUIST Departmentof Biologyand PeabodyMuseum of Natural History,Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 USA ABSTRACT.--OldWorld starlingshave been thought to be related to crowsand their allies, to weaverbirds, or to New World troupials. New World mockingbirdsand thrashershave usually been placed near the thrushesand/or wrens. DNA-DNA hybridization data indi- cated that starlingsand mockingbirdsare more closelyrelated to each other than either is to any other living taxon. Some avian systematistsdoubted this conclusion.Therefore, a more extensiveDNA hybridizationstudy was conducted,and a successfulsearch was made for other evidence of the relationshipbetween starlingsand mockingbirds.The resultssup- port our original conclusionthat the two groupsdiverged from a commonancestor in the late Oligoceneor early Miocene, about 23-28 million yearsago, and that their relationship may be expressedin our passerineclassification, based on DNA comparisons,by placing them as sistertribes in the Family Sturnidae,Superfamily Turdoidea, Parvorder Muscicapae, Suborder Passeres.Their next nearest relatives are the members of the Turdidae, including the typical thrushes,erithacine chats,and muscicapineflycatchers. Received 15 March 1983, acceptedI November1983. STARLINGS are confined to the Old World, dine thrushesinclude Turdus,Catharus, Hylocich- mockingbirdsand thrashersto the New World. la, Zootheraand Myadestes.d) Cinclusis -

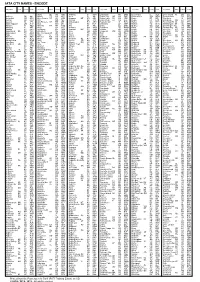

Iata City Names - Encode

IATA CITY NAMES - ENCODE City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code Alpha QL AU ABH Aribinda BF XAR Bakelalan MY BKM Beersheba IL BEV Block Island RI US BID Aalborg DK AAL Alpine TX US ALE Arica CL ARI Baker City OR US BKE Befandriana MG WBD Bloemfontein ZA BFN Aalesund NO AES Alroy Downs NT AU AYD Aripuana MT BR AIR Baker Lake NU CA YBK Beica ET BEI Blonduos IS BLO Aarhus DK AAR Alta NO ALF Arkalyk KZ AYK Bakersfield CA US BFL Beida LY LAQ Bloodvein MB CA YDV Aasiaat GL JEG Alta Floresta MT BR AFL Arkhangelsk RU ARH Bakkafjordur IS BJD Beihai CN BHY Bloomfield Ri QL AU BFC Aba/Hongyuan CN AHJ Altai MN LTI Arlit NE RLT Bakouma CF BMF Beihan YE BHN Bloomington IN US BMG Abadan IR ABD Altamira PA BR ATM Arly BF ARL Baku AZ BAK Beijing CN BJS Bloomington-NIL US BMI Abaiang KI ABF Altay CN AAT Armenia CO AXM Balakovo RU BWO Beira MZ BEW Blubber Bay BC CA XBB Abakan XU ABA Altenburg DE AOC Armidale NS AU ARM Balalae SB BAS Beirut LB BEY Blue Bell PA US BBX Abbotsford BC CA YXX Altenrhein CH ACH Arno MH AMR Balgo Hill WA AU BQW Bejaia DZ BJA Bluefield WV US BLF Abbottabad PK AAW Alto Rio Seng CB AR ARR Aroa PG AOA Bali CM BLC Bekily MG OVA Bluefields NI BEF Abbs YE EAB Alton IL US ALN Arona SB RNA Bali PG BAJ Belaga MY BLG Blumenau SC BR BNU Abeche TD AEH Altoona PA US AOO Arorae KI AIS Balikesir TR BZI Belem PA BR BEL Blythe CA US BLH Abemama KI AEA Altus OK US LTS Arrabury QL AU AAB Balikpapan ID BPN Belfast GB -

PNG Feasibility Study.Pdf

Papua New Guinea Agricultural Insurance Pre-Feasibility Study Volume I Main Report May 2013 The World Bank THE WORLD BANK Table of Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................... iii Chapter 1: Introduction and Objectives of the Study ................................................. 11 Importance of Agriculture in Papua New Guinea ......................................................... 11 Exposure of Agriculture to Natural and Climatic Hazards ........................................... 11 Government Policy for Agricultural Development ....................................................... 12 Government Request to the World Bank ...................................................................... 13 Scope and Objectives of the Feasibility Study ............................................................. 13 Report Outline ............................................................................................................... 14 Chapter 2: Agricultural Risk Assessment .................................................................... 15 Framework for Agricultural Risk Assessment and Data Requirements ....................... 15 Agricultural Production Systems in Papua New Guinea .............................................. 18 Overview of Natural and Climatic Risk Exposures to Agriculture in Papua New Guinea ........................................................................................................................... 24 Tropical -

IATA Codes for Papua New Guinea

IATA Codes for Papua New Guinea N.B. To check the official, current database of IATA Codes see: http://www.iata.org/publications/Pages/code-search.aspx City State IATA Code Airport Name Web Address Afore AFR Afore Airstrip Agaun AUP Aiambak AIH Aiambak Aiome AIE Aiome Aitape ATP Aitape Aitape TAJ Tadji Aiyura Valley AYU Aiyura Alotau GUR Ama AMF Ama Amanab AMU Amanab Amazon Bay AZB Amboin AMG Amboin Amboin KRJ Karawari Airstrip Ambunti AUJ Ambunti Andekombe ADC Andakombe Angoram AGG Angoram Anguganak AKG Anguganak Annanberg AOB Annanberg April River APR April River Aragip ARP Arawa RAW Arawa City State IATA Code Airport Name Web Address Arona AON Arona Asapa APP Asapa Aseki AEK Aseki Asirim ASZ Asirim Atkamba Mission ABP Atkamba Aua Island AUI Aua Island Aumo AUV Aumo Babase Island MKN Malekolon Baimuru VMU Baindoung BDZ Baindoung Bainyik HYF Hayfields Balimo OPU Bambu BCP Bambu Bamu BMZ Bamu Bapi BPD Bapi Airstrip Bawan BWJ Bawan Bensbach BSP Bensbach Bewani BWP Bewani Bialla, Matalilu, Ewase BAA Bialla Biangabip BPK Biangabip Biaru BRP Biaru Biniguni XBN Biniguni Boang BOV Bodinumu BNM Bodinumu Bomai BMH Bomai Boridi BPB Boridi Bosset BOT Bosset Brahman BRH Brahman 2 City State IATA Code Airport Name Web Address Buin UBI Buin Buka BUA Buki FIN Finschhafen Bulolo BUL Bulolo Bundi BNT Bundi Bunsil BXZ Cape Gloucester CGC Cape Gloucester Cape Orford CPI Cape Rodney CPN Cape Rodney Cape Vogel CVL Castori Islets DOI Doini Chungribu CVB Chungribu Dabo DAO Dabo Dalbertis DLB Dalbertis Daru DAU Daup DAF Daup Debepare DBP Debepare Denglagu Mission -

PACIFIC MANUSCRIPTS BUREAU Catalogue of South Seas

PACIFIC MANUSCRIPTS BUREAU Room 4201, Coombs Building College of Asia and the Pacific The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200 Australia Telephone: (612) 6125 2521 Fax: (612) 6125 0198 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://rspas.anu.edu.au/pambu Catalogue of South Seas Photograph Collections Chronologically arranged, including provenance (photographer or collector), title of record group, location of materials and sources of information. Amended 18, 30 June, 26 Jul 2006, 7 Aug 2007, 11 Mar, 21 Apr, 21 May, 8 Jul, 7, 12 Aug 2008, 8, 20 Jan 2009, 23 Feb 2009, 19 & 26 Mar 2009, 23 Sep 2009, 19 Oct, 26, 30 Nov, 7 Dec 2009, 26 May 2010, 7 Jul 2010; 30 Mar, 15 Apr, 3, 28 May, 2 & 14 Jun 2011, 17 Jan 2012. Date Provenance Region Record Group & Location &/or Source Range Description 1848 J. W. Newland Tahiti Daguerreotypes of natives in Location unknown. Possibly in South America and the South the Historic Photograph Sea Islands, including Queen Collection at the University of Pomare and her subjects. Ref Sydney. (Willis, 1988, p.33; SMH, 14 Mar.1848. and Davies & Stanbury, 1985, p.11). 1857- Matthew New Guinea; Macarthur family albums, Original albums in the 1866, Fortescue Vanuatu; collected by Sir William possession of Mr Macarthur- 1879 Moresby Solomon Macarthur. Stanham. Microfilm copies, Islands Mitchell Library, PXA4358-1. 1858- Paul Fonbonne Vanuatu; New 334 glass negatives and some Mitchell Library, Orig. Neg. Set 1933 Caledonia, prints. 33. Noumea, Isle of Pines c.1850s- Presbyterian Vanuatu Photograph albums - Mitchell Library, ML 1890s Church of missions. -

Marsupials and Rodents of the Admiralty Islands, Papua New Guinea Front Cover: a Recently Killed Specimen of an Adult Female Melomys Matambuai from Manus Island

Occasional Papers Museum of Texas Tech University Number xxx352 2 dayNovember month 20172014 TITLE TIMES NEW ROMAN BOLD 18 PT. MARSUPIALS AND RODENTS OF THE ADMIRALTY ISLANDS, PAPUA NEW GUINEA Front cover: A recently killed specimen of an adult female Melomys matambuai from Manus Island. Photograph courtesy of Ann Williams. MARSUPIALS AND RODENTS OF THE ADMIRALTY ISLANDS, PAPUA NEW GUINEA RONALD H. PINE, ANDREW L. MACK, AND ROBERT M. TIMM ABSTRACT We provide the first account of all non-volant, non-marine mammals recorded, whether reliably, questionably, or erroneously, from the Admiralty Islands, Papua New Guinea. Species recorded with certainty, or near certainty, are the bandicoot Echymipera cf. kalubu, the wide- spread cuscus Phalanger orientalis, the endemic (?) cuscus Spilocuscus kraemeri, the endemic rat Melomys matambuai, a recently described species of endemic rat Rattus detentus, and the commensal rats Rattus exulans and Rattus rattus. Species erroneously reported from the islands or whose presence has yet to be confirmed are the rats Melomys bougainville, Rattus mordax, Rattus praetor, and Uromys neobrittanicus. Included additional specimens to those previously reported in the literature are of Spilocuscus kraemeri and two new specimens of Melomys mat- ambuai, previously known only from the holotype and a paratype, and new specimens of Rattus exulans. The identity of a specimen previously thought to be of Spilocuscus kraemeri and said to have been taken on Bali, an island off the coast of West New Britain, does appear to be of that species, although this taxon is generally thought of as occurring only in the Admiralties and vicinity. Summaries from the literature and new information are provided on the morphology, variation, ecology, and zoogeography of the species treated. -

Biodiversity Summary: Torres Strait, Queensland

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Guide to Users Background What is the summary for and where does it come from? This summary has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. It highlights important elements of the biodiversity of the region in two ways: • Listing species which may be significant for management because they are found only in the region, mainly in the region, or they have a conservation status such as endangered or vulnerable. • Comparing the region to other parts of Australia in terms of the composition and distribution of its species, to suggest components of its biodiversity which may be nationally significant. The summary was produced using the Australian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. The list of families covered in ANHAT is shown in Appendix 1. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are are not not included included in the in the summary. • The data used for this summary come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. -

Singing Starlings Aplonis Cantoroides and Other Birds on Boigu Island, Torres Strait, Queensland

AUSTRALIAN 20 BIRD WATCHER AUSTRALIAN BIRD WATCHER 1997, 17, 20-24 Singing Starlings Aplonis cantoroides and Other Birds on Boigu Island, Torres Strait, Queensland by MIKE CARTER1, RORY O'BRIEN2 and NEIL MACUMBER3 130 Canadian Bay Road, Mt Eliza, Victoria 3930 23 Valentine Avenue, Kew, Victoria 3101 3C/- Post Office, Pomonal, Victoria 3381 Summary Ornithological reports from islands in Torres Strait are scarce. Birds seen during a visit to Boigu Island in July 1995 are listed. Significant sightings include Singing Starling Aplonis cantoroides (first authenticated record for Australia), Whiskered Tern Chlidonias hybridus, fig-parrot Cyclopsitta sp., Frilled Monarch Arses telescopthalmus, Northern Fantail Rhipidura rufiventris and House Sparrow Passer domesticus. Introduction Boigu Island is situated about 10 km south of the coast of Papua New Guinea (PNG) in Torres Strait, Queensland, at 9 °17 'S, 142 °13 'E (Draffan et al. 1983). It is the most northerly part of Australia. The island of 7150 ha has one small settlement, with most of the remainder forest and fresh-water swamp (O'Brien 1995). As a consequence of its proximity to PNG, its avifauna is more New Guinean than Australian. We visited Boigu from 18 to 20 July 1995, and here provide an annotated list of 60 species recorded (Appendix 1). All observations were within 3 km of the village. The swampy nature of the terrain makes access to most of the island difficult. We added 15 species to the 72 listed for the island by Draffan et al. (1983) in just two days, indicating the lack of ornithological reports from the island.