Fenny Skaller

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

The Origins and Operations of the Kansas City Livestock

REGULATION IN THE LIVESTOCK TRADE: THE ORIGINS AND OPERATIONS OF THE KANSAS CITY LIVESTOCK EXCHANGE 1886-1921 By 0. JAMES HAZLETT II Bachelor of Arts Kansas State University Manhattan, Kansas 1969 Master of Arts Oklahoma State University stillwater, Oklahoma 1982 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 1987 The.s; .s I q 8111 0 H~3\,.. ccy;, ;i. REGULATION IN THE LIVESTOCK TRADE: THE ORIGINS AND OPERATIONS OF THE KANSAS CITY LIVESTOCK EXCHANGE 1886-1921 Thesis Approved: Dean of the Graduate College ii 1286885 C Y R0 I GP H T by o. James Hazlett May, 1987 PREFACE This dissertation is a business history of the Kansas City Live Stock Exchange, and a study of regulation in the American West. Historians generally understand the economic growth of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and the business institutions created during that era, within the perspective of "progressive" history. According to that view, Americans shifted from a public policy of laissez faire economics to one of state regulation around the turn of the century. More recently, historians have questioned the nature of regulation in American society, and this study extends that discussion into the livestock industry of the American West. 1 This dissertation relied heavily upon the minutes of the Kansas City Live Stock Exchange. Other sources were also important, especially the minutes of the Chicago Live Stock Exchange, which made possible a comparison of the two exchanges. Critical to understanding the role of the Exchange but unavailable in Kansas City, financial data was 1Morton Keller, "The Pluralist State: American Economic Regulation in Comparative Perspective, 1900-1930," in Thomas K. -

Border Trade Advisory Committee

Job No. 2368089 1 2 3 4 5 6 BORDER TRADE ADVISORY COMMITTEE 7 8 9 10 UTEP CAMPUS, UNION BUILDING EAST 11 3RD FLOOR, ROOM 308 12 UTEP - TOMAS RIVERA CENTER 13 EL PASO, TEXAS 75205 1 4 1 5 1 6 17 SEPTEMBER 7, 2016 1 8 1 9 2 0 21 Reported by Ruth Aguilar, CSR, RPR 2 2 2 3 2 4 2 5 Page 1 Veritext Legal Solutions 800-336-4000 Job No. 2368089 1 COMMITTEE MEMBER APPEARANCE 2 SOS Carlos H. Cascos, Chair 3 Caroline Mays 4 Rafael Aldrete 5 Gabriel Gonzalez 6 Andrew Cannon 7 Paul Cristina 8 Ed Drusina 9 Veronica Escobar 10 Josue Garcia 11 Cynthia Garza-Reyes 12 Jake Giesbrecht 13 Lisa Loftus-Orway 14 Oscar Leeser 15 John B. Love, III 16 Brenda Mainwaring 17 Matthew McElroy 18 Julie Ramirez 19 Ramsey English Cantu 20 Pete Saenz 21 Gerry Schwebel 22 Tommy Taylor 23 Sam Vale 24 Juan Olaguibel 2 5 Page 2 Veritext Legal Solutions 800-336-4000 Job No. 2368089 1 MR. CASCOS: Good morning. I'm glad 2 everybody made it well. It's great to be in El Paso 3 again. I love coming to the city not just because the 4 mayor and the judge are here, but this is like my fourth 5 or fifth time I've been here and I'm going to be back 6 again in a couple of weeks and then I think Mr. Drusina is 7 telling me like we're trying to schedule or is scheduled 8 for another meeting in November to come back. -

Case 2:03-Cv-01801-MCA-LDW Document 744 Filed 04/10/07 Page 1 of 13 Pageid

Case 2:03-cv-01801-MCA-LDW Document 744 Filed 04/10/07 Page 1 of 13 PageID: <pageID> NOT FOR PUBLICATION IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY ____________________________________ ) ZEV AND LINDA WACHTEL, et al., ) Civ. Docket No. 01-4183 ) Hon. Faith S. Hochberg, U.S.D.J. Plaintiffs ) ) v. ) ) HEALTH NET, INC., HEALTH NET ) OF THE NORTHEAST, INC., and ) HEALTH NET OF NEW JERSEY, INC. ) ) Defendants. ) ____________________________________) ____________________________________ ) RENEE MCCOY, individually and on ) behalf of all others similarly situated, ) Civ. Docket No. 03-1801 ) Hon. Faith S. Hochberg, U.S.D.J. Plaintiffs ) ) OPINION v. ) ) Date: April 10, 2007 HEALTH NET, INC., HEALTH NET ) OF THE NORTHEAST, INC., and ) HEALTH NET OF NEW JERSEY, INC. ) ) Defendants. ) ____________________________________) I. Introduction: Defendants seek a stay of two orders pending resolution of a Petition for Mandamus before the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit.1 Specifically, Health Net seeks to stay compliance with two February 9, 2007 Orders, which ordered Defendants (1) to produce 1 The Court decides this motion pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 78. 1 Case 2:03-cv-01801-MCA-LDW Document 744 Filed 04/10/07 Page 2 of 13 PageID: <pageID> certain Executive Management Team (“EMT”) Minutes of Health Net Inc., Health Net of the North East, and Health Net of New Jersey (“EMT Minutes Order”);2 and (2) to produce certain out-of-network (“ONET”) regulatory documents3 of Health Net Inc. (“the ONET Regulatory Document Order”).4 These documents had been previously ordered to be produced numerous times by Magistrate Judge Shwartz; this production had been found to be incomplete. -

Adjustment to Misfortune—A Problem of Social-Psychological Rehabilitation

Adjustment to Misfortune—A Problem of Social-Psychological Rehabilitation Dedicated to the memory of Kurt Lewin TAMARA DEMBO, Ph.D.,2 GLORIA LADIEU LEVITON, Ph.D.,3 AND BEATRICE A. WRIGHT, Ph.D.4 AT PARTICULAR times in the history of To investigate the personal and social science, particular problems become ripe for problems of the physically handicapped, two investigation. A precipitating event brings groups of subjects were needed—people who them to the attention of a single person and were considered handicapped and people sometimes to that of several at the same time. around them. Therefore, as subjects of the It is therefore understandable that during research both visibly injured and noninjured World War II the need was felt to investigate people were used. Interviews were employed as the problems of social-psychological rehabilita the primary method of investigation, the tion of the physically handicapped and that great majority of the 177 injured persons someone should look for a place and the means interviewed being servicemen or veterans of to set up a research project that would try to World War II. More than half the subjects solve some of these problems. In pursuit of had suffered amputations and almost one such a goal a research group was established fourth facial disfigurements. The injured man at Stanford University on February 1, 1945. was asked questions designed to elicit his expectations, experiences, and feelings in his Conducted partially under a contract between dealings with people around him. Sixty-five Stanford University and the wartime Office noninjured people also were interviewed in of Scientific Research and Development (rec regard to their feelings toward the injured man. -

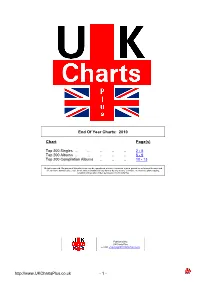

End of Year Charts: 2010

End Of Year Charts: 2010 Chart Page(s) Top 200 Singles .. .. .. .. .. 2 - 5 Top 200 Albums .. .. .. .. .. 6 - 9 Top 200 Compilation Albums .. .. .. 10 - 13 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, posted on an Internet/Intranet web site or forum, forwarded by email, or otherwise transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording without prior written permission of UKChartsPlus Published by: UKChartsPlus e-mail: [email protected] http://www.UKChartsPlus.co.uk - 1 - Symbols: Platinum (600,000) Gold (400,000) Silver (200,000) 12” Vinyl only 2010 7” Vinyl only Download only Entry Date 2010 2009 2008 2007 Title - Artist Label (Cat. No.) (w/e) High Wks 1 -- -- -- LOVE THE WAY YOU LIE - Eminem featuring Rihanna Interscope (2748233) 03/07/2010 2 28 2 -- -- -- WHEN WE COLLIDE - Matt Cardle Syco (88697837092) 25/12/2010 13 3 3 -- -- -- JUST THE WAY YOU ARE (AMAZING) - Bruno Mars Elektra ( USAT21001269) 02/10/2010 12 15 4 -- -- -- ONLY GIRL (IN THE WORLD) - Rihanna Def Jam (2755511) 06/11/2010 12 10 5 -- -- -- OMG - Usher featuring will.i.am LaFace ( USLF20900103) 03/04/2010 1 41 6 -- -- -- FIREFLIES - Owl City Island ( USUM70916628) 16/01/2010 13 51 7 -- -- -- AIRPLANES - B.o.B featuring Hayley Williams Atlantic (AT0353CD) 12/06/2010 1 31 8 -- -- -- CALIFORNIA GURLS - Katy Perry featuring Snoop Dogg Virgin (VSCDT2013) 03/07/2010 12 28 WE NO SPEAK AMERICANO - Yolanda Be Cool vs D Cup 9 -- -- -- 17/07/2010 1 26 All Around The World/Universal -

PDF File for Duplex Printing

Sexual Power for Women by Georgeann Cross Copyright © 1997 by Georgeann Cross Contents Chapter 1, In which Patrick is enslaved ........................................................................ 1 Chapter 2, In which the author gives an account of herself and this work ................... 7 Chapter 3, In which we examine the Loop .................................................................. 13 Chapter 4, In which we examine the anatomy, the physiology, and some of the psychology of male sexual response, from a practical point of view......... 19 Chapter 5, In which the reader is invited to take an inventory of herself for the purpose of gauging how well female domination might suit her ............... 27 Trustworthiness ..................................................................................... 29 Empathy ................................................................................................ 30 The ability to communicate effectively ................................................ 30 The ability to act strategically ............................................................... 31 A talent for teasing ................................................................................ 32 Attractiveness ....................................................................................... 32 Confidence ............................................................................................ 33 Chapter 6, In which we explore the advantages a man may find in being a woman’s sex slave ..................................................................................... -

New Beginnings

NEW BEGINNINGS “A bridge of silver wings stretches from the dead ashes of an unforgiving nightmare to the jeweled vision of a life started anew.” ― Aberjhani CAYEY STUDENTS WRITE [Pick the date] [Edition 1, Volume 1] NEW BEGINNINGS NEW BEGINNINGS EDITION PAPER CHIMNEY: EVERY DAY IS A NEW YEAR By: Kevin Román Candelaria & Alejandra I. Rodríguez Quiñones A few weeks ago we all to a new one? What does That’s an amazing way welcomed at the comfort that first day of January to see a new year! BUT, of our homes the have that no other day why do we bind ourselves beginning of a brand new has? Let’s see if we can to just one day? Why do year. We celebrated with find some answers. we have to wait until the our families and enjoyed very first day of a new the wonderful noise of year to decide to make a all of the fireworks being “FOR LAST YEAR'S WORDS list of the things we want projected on the skies BELONG TO LAST YEAR'S to change? above us. We’re pretty LANGUAGEAND NEXT If we really think about sure that at least a few YEAR'S WORDS AWAIT it, the 1st of January, we of us might have ANOTHER VOICE.AND TO wake up just like we wake received a visit from the MAKE AN END IS TO MAKE A up any other day of the police due to a noise BEGINNING." T. S. ELLIOT year, consequently we complaint from that could say that the first of For a lot of us, a new one grumpy neighbor January is just like any year represents a new everybody has, but none other day. -

Behind the Scenes: Uncovering Violence, Gender, and Powerful Pedagogy

Behind the Scenes: Uncovering Violence, Gender, and Powerful Pedagogy Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy Volume 5, Issue 3 | October 2018 | www.journaldialogue.org e Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy INTRODUCTION AND SCOPE Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy is an open-access, peer-reviewed journal focused on the intersection of popular culture and pedagogy. While some open-access journals charge a publication fee for authors to submit, Dialogue is committed to creating and maintaining a scholarly journal that is accessible to all —meaning that there is no charge for either the author or the reader. The Journal is interested in contributions that offer theoretical, practical, pedagogical, and historical examinations of popular culture, including interdisciplinary discussions and those which examine the connections between American and international cultures. In addition to analyses provided by contributed articles, the Journal also encourages submissions for guest editions, interviews, and reviews of books, films, conferences, music, and technology. For more information and to submit manuscripts, please visit www.journaldialogue.org or email the editors, A. S. CohenMiller, Editor-in-Chief, or Kurt Depner, Managing Editor at [email protected]. All papers in Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy are published under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share- Alike License. For details please go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/. Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy EDITORIAL TEAM A. S. CohenMiller, PhD, Editor-in-Chief, Founding Editor Anna S. CohenMiller is a qualitative methodologist who examines pedagogical practices from preK – higher education, arts-based methods and popular culture representations. -

Hamburgs Top-821-Hitliste

Hamburgs Top‐821‐Hitliste Rang Wird wann gespielt? Name des Songs Interpret 821 2010‐04‐03 04:00:00 EVERYBODY (BACKSTREET'S BACK) BACKSTREET BOYS 820 2010‐04‐03 04:03:41 GET MY PARTY ON SHAGGY 819 2010‐04‐03 04:07:08 EIN EHRENWERTES HAUS UDO JÜRGENS 818 2010‐04‐03 04:10:34 BOAT ON THE RIVER STYX 817 2010‐04‐03 04:13:41 OBSESSION AVENTURA 816 2010‐04‐03 04:27:15 MANEATER DARYL HALL & JOHN OATES 815 2010‐04‐03 04:31:22 IN MY ARMS KYLIE MINOGUE 814 2010‐04‐03 04:34:52 AN ANGEL KELLY FAMILY 813 2010‐04‐03 04:38:34 HIER KOMMT DIE MAUS STEFAN RAAB 812 2010‐04‐03 04:41:47 WHEN DOVES CRY PRINCE 811 2010‐04‐03 04:45:34 TI AMO HOWARD CARPENDALE 810 2010‐04‐03 04:49:29 UNDER THE SURFACE MARIT LARSEN 809 2010‐04‐03 04:53:33 WE ARE THE PEOPLE EMPIRE OF THE SUN 808 2010‐04‐03 04:57:26 MICHAELA BATA ILLC 807 2010‐04‐03 05:00:29 I NEED LOVE L.L. COOL J. 806 2010‐04‐03 05:03:23 I DON'T WANT TO MISS A THING AEROSMITH 805 2010‐04‐03 05:07:09 FIGHTER CHRISTINA AGUILERA 804 2010‐04‐03 05:11:14 LEBT DENN DR ALTE HOLZMICHEL NOCH...? DE RANDFICHTEN 803 2010‐04‐03 05:14:37 WHO WANTS TO LIVE FOREVER QUEEN 802 2010‐04‐03 05:18:50 THE WAY I ARE TIMBALAND FEAT. KERI HILSON 801 2010‐04‐03 05:21:39 FLASH FOR FANTASY BILLY IDOL 800 2010‐04‐03 05:35:38 GIRLFRIEND AVRIL LAVIGNE 799 2010‐04‐03 05:39:12 BETTER IN TIME LEONA LEWIS 798 2010‐04‐03 05:42:55 MANOS AL AIRE NELLY FURTADO 797 2010‐04‐03 05:46:14 NEMO NIGHTWISH 796 2010‐04‐03 05:50:19 LAUDATO SI MICKIE KRAUSE 795 2010‐04‐03 05:53:39 JUST SAY YES SNOW PATROL 794 2010‐04‐03 05:57:41 LEFT OUTSIDE ALONE ANASTACIA 793 -

Greene County 4-H

NC Cooperative Extension Greene County 4-H What’s Happening in VOLUME 3, ISSUE 3 MAY - J U N E 2 0 1 4 Greene County 4-H! Summer Day Camps Sizzle with 4-H this Summer! BBQ Chicken Plate Sale & Yard Sale 2013 Green Gar- How to be in 4-H dening Camp being lead by Club Corner– Snow Hill Pri- County Club Day mary’s School Nurse– Gena Dairy Project Byrd. 4-H Congress & State Presentation Contest Calendar of Events These events or activities are operated under the 4-H Code of Conduct and Disciplinary Procedure. The NC 4-H Code 4-H is getting geared up for another awesome summer! Come join us for our of Conduct and Disciplinary upcoming adventures in gardening, veterinary science, chickens, arts, crafts, Procedure is a condition of participation in 4-H events and games, science, and a general good time! Registration begins on May 9th and activities. will end two weeks before the camp begins. Spots are limited and will fill up For any meeting or activity in this newsletter, persons with fast so don’t delay in securing your child’s spot in one of our camps. We will be disabilities and persons with giving each participant a t-shirt with each camp (except Cool Chicks) this year! limited English proficiency may request may request accommo- For a registration form and more information on our camps please stop by our dations to participate by con- office or check out our website at greene.ces.ncsu.edu and look under News. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.