City As Landscape Masao Matsuda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AI MADONNA 1984 Born in Tokyo, Japan 2003 Graduated from Tokyo

AI☆MADONNA 1984 Born in Tokyo, Japan 2003 Graduated from Tokyo Metropolitan Senior High School of Fine Arts, Performing Arts and Classical Music / Department of Art, Design Course 2004 Graduated from Bigakko / AIDA Makoto’s Barabara Art Class 2007 Became active as AI☆MADONNA 2012 Established a company “AI☆MADONNA Production” Solo and Two Persons Exhibition: 2020 “ANIMETIC LAYERED” Roppongi Hills A/D Gallery, JP “A room missing sunlight”, Mizuma Art Gallery, Tokyo, JP 2019 “HAKUA”, 3331 Arts Chiyoda, Tokyo, JP “TRASH or TREASURE”, VV Shibuya, Tokyo, JP 2017 “A sunny and genius”, WALL Harajuku, Tokyo, JP “Ambiguous U Meeha love”, AWAJI Cafe and Gallery, Tokyo, JP 2014 “Yellow of happiness...”, VV Shibuya Udagawa, Tokyo, JP “It is not my fault that my complexion is bad”, Pixiv Zingaro, Tokyo, JP 2012 “HATSU-MOE -LOVE & Dragon-”, DIGINNER GALLERY WORKSHOP, Tokyo, JP 2011 “AI☆MADONNA Trick Art 9F”, BT gallery, Tokyo, JP 2010 “Sekirara Bishoujo Cumulonimbus”, galaxxxy, Tokyo, JP 2009 “Fruit”, antique studio MINORU, Tokyo, JP “KYUPIN”, Mizuma Action, Tokyo, JP Group Exhibitions: 2019 “A Gentle Gaze" HWA'S Gallery, Shanghai, CN "Eyes & Curiosity—Flowers in the Field" Mizuma Gallery, SG 2018 "SHIBUKARU MATSURI BY PARCO ~澀谷文化節 BY PARCO~" PMQ, HK 2017 "相沢梨紗領域-喫茶天-" AWAJI Cafe & Gallery, Tokyo, JP 2016 "Kumano Brush X Ai☆Madonna" Au Pek Osaka, Osaka, JP 2015 "Blood and Smells turn into love" PARCO GALLERY X, Tokyo, JP "SHIBUKARU MATSURI|goes to BANKOK" Bangkok, TH “JAPAN EXPO”, Paris, FR "CREATORS TOKYO" Spiral, Tokyo, JP 2014 "IMPACTS" Zen Bennett -

Deployments in JR East Under-Viaduct Spaces and Ekinaka Commercial Spaces JR East Lifestyle Business Development Headquarters

Making Best Use of Spaces in Railway Facilities Deployments in JR East Under-Viaduct Spaces and Ekinaka Commercial Spaces JR East Lifestyle Business Development Headquarters Introduction and promotes urban development by means such as formulating strategies for each line and renewing buildings ‘Thriving with Communities, Growing Globally’ is the near stations in accordance with the strategy. This promotes catchphrase for the JR East Group Management Vision development that makes use of site features. V — Ever Onward released in October 2012. In ‘Thriving Third, JR East is coordinating with local governments with Communities’, JR East ‘draws a blueprint for the future and others to promote urban development centring on together with members of the community as it does its part stations in provincial core cities facing population decline. to build vibrant communities’. The company is making coordinated efforts with local In lifestyle services, JR East is promoting ‘attractive governments to revitalize communities and enhance public urban development centred on stations’. This is done by functions and community functions by renovating station dealing with changes in the business environment, such facilities and updating buildings near stations. It is also as ageing of society and globalization, and demands from aiming for stations to become the ‘face’ of the city and entire customers and the community while consolidating attractive surrounding area with high-level convenience for both locals services and functions at stations. Stations are the ‘face’ and visitors by enhancing gateway functions, etc. of the town and by going forward with three types of urban development in line with these features, JR East is aiming for Efforts to Increase Trackside Value by stations that can be venues where people can interact. -

Discover Tokyo C1

DISCOVER TOKYO An Unforgettable School Trip Contact:[email protected] Experience Fascinating Japan in Tokyo, Where Old Meets New Tokyo is a metropolis like no other. A sprawling city where ancient meets modern, Tokyo has served as the pulsating heart of Japan for over 400 years. Tourists flock here from around the world to sample the city’s one-of-a-kind atmosphere. While embracing legacy and tradition, the city is forever in flux. Come to Tokyo and you are guaranteed an unforgettable experience. 5 Reasons to Choose Tokyo for School Trips 1 Safety and Security Any destination you choose for a school trip must be safe and it must provide a sense of security. According to the “Safe Cities Index 2017” report compiled by UK-based news magazine The Economist, Tokyo ranks as the safest major city in the world. Visitors and locals alike appreciate this aspect of the city, along with its notable cleanliness. Safe and clean Tokyo therefore makes an ideal destination for a school trip. 2 Japan’s Economic Heart Tokyo is an international center of economic activity. By itself, it accounts for around 20% of Japan’s GDP—a figure that puts it on a par with the entire country of Mexico. The bustling streets of Tokyo never fail to amaze visitors to the city. Another draw for anyone planning a school trip here is the abundance of industry- and economy-related facilities that welcome visiting tour groups. 3 The Hub of Japan With two international airports, Haneda and Narita, Tokyo is Japan’s main gateway to the world. -

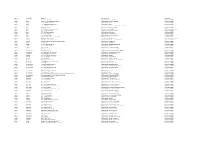

Area Locality Address Description Operator Aichi Aisai 10-1

Area Locality Address Description Operator Aichi Aisai 10-1,Kitaishikicho McDonald's Saya Ustore MobilepointBB Aichi Aisai 2283-60,Syobatachobensaiten McDonald's Syobata PIAGO MobilepointBB Aichi Ama 2-158,Nishiki,Kaniecho McDonald's Kanie MobilepointBB Aichi Ama 26-1,Nagamaki,Oharucho McDonald's Oharu MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 1-18-2 Mikawaanjocho Tokaido Shinkansen Mikawa-Anjo Station NTT Communications Aichi Anjo 16-5 Fukamachi McDonald's FukamaPIAGO MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 2-1-6 Mikawaanjohommachi Mikawa Anjo City Hotel NTT Communications Aichi Anjo 3-1-8 Sumiyoshicho McDonald's Anjiyoitoyokado MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 3-5-22 Sumiyoshicho McDonald's Anjoandei MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 36-2 Sakuraicho McDonald's Anjosakurai MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 6-8 Hamatomicho McDonald's Anjokoronaworld MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo Yokoyamachiyohama Tekami62 McDonald's Anjo MobilepointBB Aichi Chiryu 128 Naka Nakamachi Chiryu Saintpia Hotel NTT Communications Aichi Chiryu 18-1,Nagashinochooyama McDonald's Chiryu Gyararie APITA MobilepointBB Aichi Chiryu Kamishigehara Higashi Hatsuchiyo 33-1 McDonald's 155Chiryu MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 1-1 Ichoden McDonald's Higashiura MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 1-1711 Shimizugaoka McDonald's Chitashimizugaoka MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 1-3 Aguiazaekimae McDonald's Agui MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 24-1 Tasaki McDonald's Taketoyo PIAGO MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 67?8,Ogawa,Higashiuracho McDonald's Higashiura JUSCO MobilepointBB Aichi Gamagoori 1-3,Kashimacho McDonald's Gamagoori CAINZ HOME MobilepointBB Aichi Gamagori 1-1,Yuihama,Takenoyacho -

New Value for New Growth

SUMITOMO REALTY & DEVELOPMENT CO., LTD. ANNUAL REPORT 2012 ANNUAL REPORT & DEVELOPMENT CO., LTD. SUMITOMO REALTY New Value for New Growth Annual Report 2012 Profile About the Company Sumitomo Realty & Development Co., Ltd., a core member of the Sumitomo Group, is one of Japan’s leading real estate companies. The Company is well established as a comprehensive developer and supplier of high-quality office buildings and condominiums in urban areas. With operations centered on four areas—leasing, sales, construction and brokerage—the Company has achieved a combination of growth potential and balanced operations that will drive its success in the challenging markets of the 21st century. Sumitomo Realty remains committed to the creation of comfortable work and living environments that contribute to a higher quality of life. Shinjuku NS Building (Head office) Our History 1949–80 81–2000 ■1949 Izumi Real Estate Co., Ltd. established as the ■1982 Completed construction of 30-story Shinjuku NS successor to the holding company of the Sumitomo Building in Shinjuku, Tokyo; moved Company zaibatsu following the breakup of the conglomerate. headquarters there from Shinjuku Sumitomo Building. ■1957 Izumi Real Estate Co., Ltd. changed its name to ■1995 Commenced American Comfort custom home Sumitomo Realty & Development Co., Ltd. construction business. ■1963 Merged with the holding company of the former ■1996 Commenced Shinchiku Sokkurisan remodeling Sumitomo zaibatsu during its liquidation. business. ■1964 Entered condominium sales business with Hama- ■1997 Entered high-quality business hotel market. Opened Ashiya Mansion in Kobe, Hyogo Prefecture. Villa Fontaine Nihonbashi and hotels at two other locations. ■1970 Listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange and Osaka Securities Exchange. -

NOTICE 10.00 A.M., June 10, 1947

ENGLISH 80VEEH1EMT JStlllN§ BUHEAU EDITION sm-i-jm-jih+bbewmmihw EXTRA SATURDAY, MARCH 29, 1947 sheet is hereby requested to notify his claim on the said bill of exchange and submit the same to this Court by 4. NOTICE 10.00 a.m., June 10, 1947. In case of failure to notify of and submit the same PUBLIC NOTICE in accordance with the preceding paragraph by the date fixed, the said bill of exchange may be declared null and void. August 31,' -1946 Tokyo Local Court No. 2339 (Annexed sheet abridged) Name: Ryolchi Ayabe Address : No. 1, Miyamoto-cho, Kanda-ku, Tokyo. No. 2343 September 25, 1946 Name : Kan SansakI No. 1067 Address : No. 764, Fujisawa, Fujlsawa-shi, Kanagawa- Name : Takeklchi Nishimoto ken. Address : No. 8, Shibano-machi Wakayama-shi.'1' T, No. 2347 ; At the Instance of the abovementioned person the Name: \ Teiltsu Baba bearers of share certificates shown on the annexed sheet Address : No. 33, Shitayaguchi, Ishulo-machi, Hioki- are hereby requested to notify their claims on the said gun, Kagoshlma-ken- certificates and submit the same to this Court by 10.00 No. 2358 a.m., April 21,- 1947 Name : Eijiro Hayano In case of failure to notify of and submit the same Address : No. 1-1* Hlrokojinisiiidori, Nakamura-ku, in accordance with the preceding paragraph by the date fixed, the said share certificates may be declared null Nagoya. and void. < \ At the instances of the abovernentioned persons Tokyo Local Court the bearers of share certificates shown on the annexed (Annexed sheet abridged) sheets are hereby requested to notify their claims on the said certificates and submit the same to this Court by 10.00 a.m., May 20, 1947. -

Area Adress Shop Name Sightseeing Accommodations Food&Drink

Area Adress Shop name Sightseeing Accommodations Food&Drink Activities Shopping Activities 392 Asahi Kuttyan-chomati Abuta-gun, Hokkaidou White Isle NISEKO ○ 145-2 Hirafu, Kutchan-cho, Abuta-gun, Hokkaido BOUKEN KAZOKU ○○○ Tanuki-koji Arcade, 5-chome, Minami-sanjo-nishi, Chuo-ku, Sapporo-shi, Hokkaido Izakaya Sakanaya Shichifukujin-Shoten Tanukikoji○ Japan Land Building 4F, 5 chome, Minami Gojo Nishi, Chuo-ku, Sapporo-shi, Hokkaido KYODORYORI NAGAI ○ 2 chome, Minami 5 jo Nishi, Abashiri-shi, Hokkaido YAKINIKU RIKI ○ 3434 kita34gou nisi9sen Kamifurano-cho, Sorachi-gun, Hokkaido WOODY LIFE ○○ 1-1-6 Hanazono, Otaru-shi, Hokkaido TATSUMI SUSHI ○ 3-5 Naruka, Toyakocho, Abuta-gun, Hokkaido SILO TENBOUDAI ○○○ 2-22 Saiwaicho, Furano-shi, Hokkaido Okonomiyaki - Senya ○ Daini Green Bldg. 1F, Minami4jonishi 3-chome, Chuo-ku, Sapporo-shi, Hokkaido(next to Susukino police booth) CHINESE RESTAURANT SAI-SAI ○ Minami6jo-dori 19-2182-103, Ashikawa-shi, Hokkaido Local Sake Storehouse - Taisetsu no Kura ○ ○ ○ 12-6 Toyokawacho, Hakodate-shi, Hokkaido LA VISTA Hakodate Bay ○ Asahidake-Onsen, Higashikawacho, Kamikawa-gun, Hokkaido La Vista Daisetsuzan ○ 4 Tanuki Koji, Nishi-4Chome, Minami-3jo, Chuoku, Sapporo-shi, Hokkaido BIG SOUVENIR SHOP TANUKIYA ○ Hotel Parkhills,Shiroganeonsen,Biei-cho,Kamikawa-gun,Hokkaido HOTEL PARKHILLS ○ ○ ○ 1-1 Otemachi, Hakodate-shi, Hokkaido Hotel Chocolat Hakodate ○ Shiroganeonsen,Biei-cho,Kamikawa-gun,Hokkaido SHIROGANE ONSEN HOTSPRING ○ ○ ○ 142-5, Toyako Onsen, Toyako-cho, Abuta-gun, Hokkaido TOYAKO VISITOR CENTE/VOLCANO SCIENCE -

Tabegotoya-Norabo URL

Suginami ☎ 03-3395-7251 Tabegotoya-Norabo URL 4-3-5Nishiogikita, Suginami-ku 12 9 3 6 17:00 – 0:00 Mondays 7 min. from Chuo Line Nishiogikubo Station North Exit Signature menu Local vegetables and Kakiage tempura with corn and ★ tofu salad edamame soybeans Available Year-round Available June-July Ingredients (Almost completely) Uses Ingredients Corn and edamame soybeans used seasonal vegetables from used from Mitaka City Mitaka City Nishi-Ogikubo Toshima ☎ 03-3988-1161 Royal Garden Cafe MEJIRO URL https://royal-gardencafe.com/mejiro/ 2F TRAD Mejiro, 2-39-1 Mejiro, Toshima-ku 12 9 3 6 Mondays-Saturdays: 11:00 – 23:00 Sundays: 11:00 – 22:00 New Year Holidays (New Year's Eve/New Year's Day) Immediately from JR Mejiro Station Signature menu Recommended Seasonal Tokyo Vegetables Menu (Menu varies by season) ★ Available Year-round MejiroMejiro Ingredients Seasonal vegetables from Tokyo and Edo Tokyo used 54 Yofu Souzai Teppan Daidokoro ☎ 03-6454-4252 Kita Theory Akabane URL https://www.hotpepper.jp/strJ001162446/ 1-29-7 Akabane, Kita-ku 12 9 3 6 Mon. 18:30 – 22:00 Tue – Sun 12:00 – 15:00/17:30 – 22:00 Mondays 5 min. walk from JR Akabane Station East Exit Signature menu Cabbage with Salt-Based ★ Hiroshima Yaki Sauce Available Year-round Available Year-round Ingredients Ingredients cabbages from Nerima cabbages from Nerima used used AkabaneAkabane ☎ 03-3894-4226 Arakawa Izumiya Home Cooking URL http://www.yuenchidori.com 6-30-9 Nishiogu, Arakawa-ku 12 9 3 6 11:00 – 14:00/17:00 – 22:00 Tuesdays 2 min. -

2018 ANNUAL REPORT (April 1, 2017~March 31, 2018)

2018ANNUALREPORT 2018 ANNUAL REPORT (April 1, 2017~March 31, 2018) SMBC信託銀行2018_EN_1-4.indd 4-1 2018/08/01 9:44 Please note that this material is an English translation of the Japanese original for reference purposes only without Public Notice of Financial Results any warranty as to its accuracy or completeness. Please be advised that there may be some disparities due Public notice of financial results required under Article 20 of the Banking Act is posted on SMBC Trust’s website to such things as differences in nuance that are inherent to the difference in languages although the English from the current fiscal year. translation is prepared to mirror the Japanese original as accurately as possible. ● http://www.smbctb.co.jp/contents/aboutus ● Click “Financial Report” under “Company Profile” Website SMBC Trust Bank top page https://www.smbctb.co.jp https://www.smbctb.co.jp/en About SMBC Trust Bank https://www.smbctb.co.jp/contents/aboutus https://www.smbctb.co.jp/en/contents/aboutus This book is a disclosure material (explanation materials for business and property) which is prepared based on Article 21 of the Banking Act and Article 19 (2) of the Ordinance for Enforcement of the Banking Act. SMBC信託銀行2018_EN_1-4.indd 2-3 2018/08/01 9:44 Philosophy Corporate Management Please note that this material is an English translation of the Japanese original for reference purposes only without any warranty as to its accuracy or completeness. Please be advised that there may be some disparities due Contents to such things as differences in nuance that are inherent to the difference in languages although the English translation is prepared to mirror the Japanese original as accurately as possible. -

Nishiogikubo

http://experience-suginami.tokyo/ NISHI-OGIKUBO NISHIOGI LOVERS FES 0 100 200 LUNCH & DINNER MOMOI HARAPPA PARK DINNER 桃井はらっぱ公園 and by all means get on the Chuo-Line and come to Suginami. to come and Chuo-Line the on get means all by and for some Tokyo sightseeing or wandering, please take a look at this page page this at look a take please wandering, or sightseeing Tokyo some for OME KAIDO St. Japan who are living and/or working in Suginami. If you are headed out out headed are you If Suginami. in working and/or living are who Japan 青梅街道 charm of these local areas will be introduced here by foreign residents in in residents foreign by here introduced be will areas local these of charm HOSPITAL music venues, and an anime district. These kinds of spots or even just the the just even or spots of kinds These district. anime an and venues, music Photographer: Sho izakaya and bars, second hand clothing and book stores, antique shops, shops, antique stores, book and clothing hand second bars, and izakaya FIRE STATION IOGI PRIMARY SCHOOL Nishiogi Lovers Fes was held at Momoi harappa park which is 井荻小学校 POLICE STATION unique spots scattered about including restaurants, ramen shops, shops, ramen restaurants, including about scattered spots unique placed between Nishi-ogikubo and Ogikubo for the first time on round in this area you can enjoy various events and there are a variety of of variety a are there and events various enjoy can you area this in round 3rd of March 2016. -

Gyu-Kaku Japan Store List * Capital Region Only

* As of September 19, 2011 Gyu-Kaku Japan Store List * Capital region only. Other area will be updating soon. Store Name *Alphabetical Post Code Address TEL Nearest Station Tokyo Gyu-Kaku Akabane 1150045 1-21-3-1F Akabane, Kita-ku, Tokyo 0352495529 Akabane Station Gyu-Kaku Akasakamitsuke 1070052 3-10-10-2F Higashiomiya, Minumaku, Saitama-shi, Saitama 0355726129 Akasakamitsuke Station Gyu-Kaku Akihabara Ekimae 1010021 1-15-9-8F Sotokanda, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 0352971929 Akihabara Station Gyu-Kaku Akihabara Showa-dori-guchi 1010025 1-24 Sakumacho, Kanda, Chiyoda-ku 0335266029 Akihabara Station Gyu-Kaku Akiruno 1970804 1-15-6 Akigawa, Akiruno-shi, Tokyo 0425324531 Akigawa Station Gyu-Kaku Akishima 1960015 5-14-17-1F Showacho, Akishima-shi, Tokyo 0425491929 Akishima Station Gyu-Kaku Akishima Mori-town 1960014 562-1-3F Tanakacho, Akishima-shi, Tokyo 0425006329 Akishima Station Gyu-Kaku Akitsu 2040004 5-298-5-2F Noshio, Kiyose-shi, Tokyo 0424967129 Akitsu Station Gyu-Kaku Aoto 1240012 6-30-8-2F Tateishi, Katsushika-ku, Tokyo 0356718929 Aoto Station Gyu-Kaku Asagayakitaguchi 1660001 2-1-3-3F Asagayakita, Suginami-ku, Tokyo 0353275629 Asagaya Station Gyu-Kaku Asakusa 1110032 1-32-11-B1F Asakusa, Taito-ku, Tokyo 0358305929 Asakusa Station Gyu-Kaku Asakusa Kokusaidori 1110035 2-13-9-2F Nishiasakusa, Taito-ku, Tokyo 0358272120 Tawaramachi Station Gyu-Kaku Asakusabashi 1110053 2-29-13-2F Asakusaba-shi, Taito-ku, Tokyo 0358351129 Asakusabashi Station Gyu-Kaku Awashimadori 1540005 2-38-7-1F Mishuku, Setagaya-ku, Tokyo 0357796829 Ikenoue Station Gyu-Kaku -

Leveraging Potential to Generate Profit

Leveraging Potential to Generate Profit Annual Report 2013 Who We Are... Our History 1949 Izumi Real Estate Co., Ltd. established Sumitomo Realty & Development Co., Ltd., a core as the successor to the holding company member of the Sumitomo Group, is one of Japan’s of the Sumitomo zaibatsu following the breakup of the conglomerate. leading real estate companies. 1957 Izumi Real Estate Co., Ltd. changed its The Company is well established as a compre- name to Sumitomo Realty & hensive developer and supplier of high-quality office Development Co., Ltd. buildings and condominiums in urban areas. 1963 Merged with the holding company of the With operations centered on four areas—leasing, former Sumitomo zaibatsu during sales, construction and brokerage—the Company has its liquidation. achieved a combination of growth potential and bal- 1964 Entered condominium sales business anced operations that will drive its success in the with Hama- Ashiya Mansion in Kobe, Hyogo Prefecture. challenging markets of the 21st century. Sumitomo 1970 Listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange and Realty remains committed to the creation of comfort- Osaka Securities Exchange. able work and living environments that contribute to 1973 Established Sumitomo Fudosan a higher quality of life. Tatemono Service Co., Ltd., a consoli- dated subsidiary. 1974 Completed construction of 52-story Shinjuku Sumitomo Building in Shinjuku, Tokyo; moved Company headquarters there from Tokyo Sumitomo Building in Marunouchi, Tokyo. 1975 Established Sumitomo Real Estate Sales Co., Ltd., a consolidated subsidiary. 1980 Established Sumitomo Fudosan Syscon Co., Ltd., a consolidated subsidiary. 1949 1960 Global Events 1964 • Tokyo Olympic Games 1973 • First oil crisis 1978 • Second oil crisis Shinjuku NS Building (Head office) Our History 1982 Completed construction of 2001 The number of managed STEP 2011 Opened Grand Mansion Gallery.