University Musical Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leonard Bernstein

Leonard Bernstein Arias and Barcarolles (Bright Sheng version) 1988 31 min for mezzo and baritone, strings and percussion Orchestrated with the assistance of Bright Sheng perc(2):xyl/glsp/vib/small cym/small SD/large SD/chimes/small BD/ tamb/tgl/crotales/small tam-t/police whistle/small wdbl/large wdbl/ small susp.cym/TD-strings Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world Arias and Barcarolles (Bruce Coughlin version) Leonard Bernstein photo © Susech Batah, Berlin (DG) Leonard Bernstein, arranged by Bruce Coughlin 1988, arr. 1993 31 min VOICE(S) AND ORCHESTRA arranged for mezzo-soprano, baritone and chamber orchestra 1(=picc).1(=corA).1(=Ebcl,asax).1-2.1.0.0-perc(2):timp/SD/low tom-t/ 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue trap set(hi-hat cym/ride cym/BD)/cyms/susp.cym/low gong/crot/ slapstick/rainstick/auto brake dr/police whistle/tamb/tgl/wdbl/ Selections for concert performance glsp/xyl/vib-strings(8.8.6.6.3 or 1.1.1.1.1) 1976 Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world for solo voice and orchestra Bernstein's Blues Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world Leonard Bernstein, arranged by Sid Ramin 2003 14 min 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue a suite of four songs arranged for voice and orchestra: Ain't Got No Tears Take Care of this House Left, Lonely Me, Screwed On Wrong, Big Stuff 1976 4 min 2.2.2.2.asax.tsax.barisax-2.2.2.1-timp-perc(trap set)-gtr-pft-strings for voice and orchestra Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world 1.1.2.bcl.1-2.2.2.1-perc(2):timp/xyl/bells-harp-guitar-pft-strings -

Haydn London Symphony

Portrait of Franz Joseph Haydn by Thomas Hardy, 1791 WHAT MAKES IT GREAT?® HAYDN LONDON SYMPHONY 20 CONCERT PROGRAM Louis Babin Friday, February 10, 2017 Retrouvailles: Sesquie for Canada’s 150th* 7:30pm (TSO PREMIÈRE/TSO CO-COMMISSION) Rob Kapilow Rob Kapilow What Makes It Great?® conductor & host Haydn London Symphony Gary Kulesha* conductor Intermission Franz Joseph Haydn Symphony No. 104 in D Major “London” I. Adagio – Allegro II. Andante III. Menuet: Allegro IV. Allegro spiritoso Audience Q&A with Rob Kapilow and Orchestra Please note that Louis Babin’s Retrouvailles is being recorded for online release at TSO.CA/CanadaMosaic. Tonight’s What Makes It Great?® program is all about listening. Paying attention. Noticing all the fantastic things in great music that race by at lightning speed, note by note, and measure by measure. Listening to a piece of music from the composer’s point of view—from the inside out. During the first half of the concert, we will look at selected passages from Franz Joseph Haydn’s Symphony No. 104 (“London”) and I will do everything in my power to get you inside the piece to Rob Kapilow hear what makes it tick and what makes it great. Then, after intermission, we will conductor perform the piece in its entirety, and you will hopefully listen to it with a whole & host new pair of ears. I am thrilled to be sharing this great music with you tonight. All you have to do is listen. 21 For a program note to Louis Babin’s Retrouvailles: Sesquie THE DETAILS for Canada’s 150th, please turn to pg. -

National Arts Awards Monday, October 19, 2015

2015 Americans for the Arts National Arts Awards Monday, October 19, 2015 Welcome from Robert L. Lynch Performance by YoungArts Alumni President and CEO of Americans for the Arts Musical Director, Jake Goldbas Philanthropy in the Arts Award Legacy Award Joan and Irwin Jacobs Maria Arena Bell Presented by Christopher Ashley Presented by Jeff Koons Outstanding Contributions to the Arts Award Young Artist Award Herbie Hancock Lady Gaga 1 Presented by Paul Simon Presented by Klaus Biesenbach Arts Education Award Carolyn Clark Powers Alice Walton Lifetime Achievement Award Presented by Agnes Gund Sophia Loren Presented by Rob Marshall Dinner Closing Remarks Remarks by Robert L. Lynch and Abel Lopez, Chair, introduction of Carolyn Clark Powers Americans for the Arts Board of Directors and Robert L. Lynch Remarks by Carolyn Clark Powers Chair, National Arts Awards Greetings from the Board Chair and President Welcome to the 2015 National Arts Awards as Americans for the Arts celebrates its 55th year of advancing the arts and arts education throughout the nation. This year marks another milestone as it is also the 50th anniversary of President Johnson’s signing of the act that created America’s two federal cultural agencies: the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Americans for the Arts was there behind the scenes at the beginning and continues as the chief advocate for federal, state, and local support for the arts including the annual NEA budget. Each year with your help we make the case for the funding that fuels creativity and innovation in communities across the United States. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

PDF 139.88KB Rps Abo Salomon Prize 2013

Press Release For release: Friday 10 January 2014 ‘Unsung heroine’ of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, violinist Catherine Arlidge, a “true advocate of the modern orchestral musician” awarded prestigious RPS/ABO Salomon Prize for orchestral musicians. Catherine Arlidge of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra becomes the first violinist – and only the third ever recipient – of the RPS/ABO Salomon Prize, a prestigious award celebrating the outstanding contribution of orchestral players to the UK’s musical life. The UK boasts many of the world’s finest orchestras, many of which have trophy cabinets bursting with awards in testimony to their brilliance on the concert platform and in the recording studio. Yet, the contribution of individual musicians within an orchestra often goes unnoticed. The Salomon Prize* was created by the Royal Philharmonic Society and Association of British Orchestras in 2011 to celebrate the ‘unsung heroes’ of orchestral life; the orchestral players that make our orchestras great. The award is named after Johann Peter Salomon, violinist and founding member of the Philharmonic Society in 1813. Each year, players in all orchestras across the UK are asked to nominate a colleague who has been ‘an inspiration to their fellow players, fostered greater spirit of teamwork and shown commitment and dedication above and beyond the call of duty’. Catherine Arlidge, Sub Principal of the second violins, who has played with the CBSO for over 20 years, was nominated by her fellow musicians and the CBSO’s management for her creativity, energy and “great skill for motivating and inspiring colleagues and for engaging with her audience”. -

Andrè Schuen’S Repertory Ranges from Early Music to Contemporary Music, and He Is Equally Comfortable in the Genres of Oratorio, Lied and Opera

A NDRÈ S CHUEN - Baritone Born in 1984, he studied at the Mozarteum of Salzburg with Gudrun Volkert, Horiana Branisteanu, Josef Wallnig and Hermann Keckeis (opera), and with Wolfgang Holzmair (Lied and oratorio). He has appeared as soloist of Salzburg Concert Association, Collegium Musicum Salzburg, Salzburg Bach Society, and has already sung with such renowned orchestras as Wiener Philharmoniker, Mozarteum Orchestra and Camerata Salzburg, with such conductor as Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Philippe Jordan, Simon Rattle, Ivor Bolton, Roger Norrington and Ingo Metzmacher. Andrè Schuen’s repertory ranges from early music to contemporary music, and he is equally comfortable in the genres of oratorio, lied and opera. Concerts, festivals and tv appearances have taken him to Vienna, Berlin, Munich, Dresden, Zurich, Tokyo, Puebla (Mexico), Buenos Aires and Ushuaia (Argentina). At the Salzburg Festival in 2006, he sang the bass choral solo in Mozart’s Idomeneo under Roger Norrington. During the 2007/08 season, he performed the role of Ein Lakai in Ariadne auf Naxos under Ivor Bolton in a new production of Salzburg State Theater at the Haus für Mozart. He also performed the role of Figaro in Le nozze di Figaro at Mozarteum in Salzburg and at various theaters in Germany and Austria. In August of 2009, he sang as Basso I in Luigi Nono’s Al gran sole carico d’amore at Salzburg Festival, conducted by Ingo Metzmacher. In August of 2009 he was awarded the “Walter-und- Charlotte-Hamel-Stiftung” and the “Internationale Sommerakademie Mozarteum Salzburg”. In the summer of 2010 he took part in the Young Singers Project at Salzburg Festival. -

Quartet Dimensions

concert program ii: Quartet Dimensions JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685–1750)! July 21 WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756–1791) Sunday, July 21, 6:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts Fugue in E-flat Major, BWV 876, and Fugue in d minor, BWV 877, from at Menlo-Atherton Das wohltemperierte Klavier; arr. String Quartets nos. 7 and 8, K. 405 JOSEPH HAYDN (1732–1809) PROGRAM OVERVIEW String Quartet in d minor, op. 76, no. 2, Quinten (1796) The string quartet medium, arguably the spinal column of the Allegro chamber music literature, did not exist in Bach’s lifetime. Yet Andante o più tosto allegretto Minuetto: Allegro ma non troppo even here, Bach’s legacy is inescapable. The fugues of his semi- Finale: Vivace assai nal The Well-Tempered Clavier inspired no less a genius than Danish String Quartet: Frederik Øland, Rune Tonsgaard Sørensen, violins; Asbjørn Nørgaard, viola; Mozart, who arranged a set of them for string quartet. The influ- Fredrik Schøyen Sjölin, cello ence of Bach’s architectural mastery permeates the ingenious DMITRY SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–1975) Quinten Quartet of Joseph Haydn, the father of the modern Piano Quintet in g minor, op. 57 (1940) string quartet, and even Dmitry Shostakovich’s Piano Quintet, Prelude composed nearly two hundred years after Bach’s death. The Fugue Scherzo centerpiece of Beethoven’s Opus 132—the Heiliger Dankgesang Intermezzo CONCERT PROGRAMSCONCERT eines Genesenen an die Gottheit (“A Convalescent’s Holy Song Finale PROGRAMSCONCERT of Thanksgiving to the Divinity”)—recalls another Bachian signa- Gilbert Kalish, piano; Danish String Quartet: Frederik Øland, Rune Tonsgaard Sørensen, violins; ture: the Baroque master’s sacred chorales. -

Joseph Haydn

The Creation JOSEPH HAYDN First Metropolitan United Church March 14, 2020 The Program Victoria Philharmonic Choir It’s Music to OurMusic Ears to... Our Ears Harmonizing self-interest with environmental welfare Haydn’s The Creation is a majestic where the tiny hummingbird could pick is a majestic ode to the glorious qualities of Haydn’s The Creation ode to the glorious qualities of our planet up only a drop of water at a time to try to our planet Earth as a safe home for humanity. TheHarmonizing story confirms why we should quench a raging forest fire. She pointed hold our Earth in awe as a special place in the cosmos where humanity can thrive Earth as a safe home for humanity. The out that she was doing everything she in spirit and in wellbeing. self-interest story confirms why we should hold our Earth in awe as a special place in the could to save the forest. The challenge The power of the work reminds us of living within nature’s limits. Unfortunately, cosmos where humanity can thrive in of the Legacy Series is to inspire all of us carbon gas buildup in our atmosphere and the withcontinuing loss of biodiversity spirit and in well-being. to do all we can to protect this precious though large-scale human activity has pushed us beyond Earth’s natural limits. Earth. In response, the United Nations continues toplanetary urge all nations to return to carbon The power of the work reminds us of living neutrality by 2050. This means that the natural capacity of the Earths’ ecosystems within nature’s limits. -

Handel's Messiah Freiburg Baroque Orchestra

Handel’s Messiah Freiburg Baroque Orchestra Wednesday 11 December 2019 7pm, Hall Handel Messiah Freiburg Baroque Orchestra Zürcher Sing-Akademie Trevor Pinnock director Katherine Watson soprano Claudia Huckle contralto James Way tenor Ashley Riches bass-baritone Matthias von der Tann Matthias von There will be one interval of 20 minutes between Part 1 and Part 2 Part of Barbican Presents 2019–20 Please do ... Turn off watch alarms and phones during the performance. Please don’t ... Take photos or make recordings during the performance. Use a hearing aid? Please use our induction loop – just switch your hearing aid to T setting on entering the hall. The City of London Corporation Programme produced by Harriet Smith; is the founder and advertising by Cabbell (tel 020 3603 7930) principal funder of the Barbican Centre Welcome This evening we’re delighted to welcome It was a revolutionary work in several the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra and respects: drawing exclusively on passages Zürcher Sing-Akademie together with four from the Bible, Handel made the most of outstanding vocal soloists under the his experience as an opera composer in direction of Trevor Pinnock. The concert creating a compelling drama, with the features a single masterpiece: Handel’s chorus taking an unusually central role. To Messiah. the mix, this most cosmopolitan of figures added the full gamut of national styles, It’s a work so central to the repertoire that from the French-style overture via the it’s easy to forget that it was written at a chorale tradition of his native Germany to time when Handel’s stock was not exactly the Italianate ‘Pastoral Symphony’. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 113, 1993-1994

Boston Symphony Orchestra Twentieth Anniversary Season 19 9 3-94 *,* 'K> ye €B€L the architects of ti m e beluQO Soft and elegant. Hand sculpted in Switzerland exclusively in 18 karat gold. Water resistant Five year international limited warranty. Intelligently priced. E.B. HORN Jewelers Since 1839 Positively The Best Value In Jewelry 429 WASHINGTON ST BOSTON 02108 ALL MAJOR CREDIT CARDS ACCEPTED • BUDGET TERMS MAIL OR PHONE ORDERS 542-3902 • OPEN MON. AND THURS. TIL 7 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director One Hundred and Thirteenth Season, 1993-94 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. J. P. Barger, Chairman George H. Kidder, President Mrs. Lewis S. Dabney, Vice-Chairman Nicholas T. Zervas, Vice-Chairman Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman andTreasurer David B. Arnold, Jr. Nina L. Doggett George Krupp Peter A. Brooke Dean Freed R. Willis Leith, Jr. James F. Cleary Avram J. Goldberg Mrs. August R. Meyer John F. Cogan, Jr. Thelma E. Goldberg Molly Beals Millman Julian Cohen Julian T. Houston Mrs. Robert B. Newman William F. Connell Mrs. BelaT. Kalman Peter C. Read William M. Crozier, Jr. Allen Z. Kluchman Richard A. Smith Deborah B. Davis Harvey Chet Krentzman Ray Stata Trustees Emeriti Vernon R. Alden Archie C. Epps Irving W. Rabb Philip K. Allen Mrs. Harris Fahnestock Mrs. George Lee Sargent Allen G. Barry Mrs. John L. Grandin Sidney Stoneman Leo L. Beranek Mrs. George I. Kaplan John Hoyt Stookey AbramT. Collier Albert L. Nickerson John L. Thorndike Nelson J. Darling, Jr. Thomas D. Perry, Jr. Other Officers of the Corporation John Ex Rodgers, Assistant Treasurer Michael G. -

Newsletter • Bulletin

NATIONAL CAPITAL OPERA SOCIETY • SOCIETE D'OPERA DE LA CAPITALE NATIONALE Newsletter • Bulletin Summer 2000 L’Été A WINTER OPERA BREAK IN NEW YORK by Shelagh Williams The Sunday afternoon programme at Alice Tully Having seen their ads and talked to Helen Glover, their Hall was a remarkable collaboration of poetry and words new Ottawa representative, we were eager participants and music combining the poetry of Emily Dickinson in the February “Musical Treasures of New York” ar- recited by Julie Harris and seventeen songs by ten dif- ranged by Pro Musica Tours. ferent composers, sung by Renee Fleming. A lecture We left Ottawa early Saturday morning in our bright preceded the concert and it was followed by having most pink (and easily spotted!) 417 Line Bus and had a safe of the composers, including Andre Previn, join the per- and swift trip to the Belvedere Hotel on 48th St. Greeted formers on stage for the applause. An unusual and en- by Larry Edelson, owner/director and tour leader, we joyable afternoon. met our fellow opera-lovers (six from Ottawa, one from Monday evening was the Met’s block-buster pre- Toronto, five Americans and three ladies from Japan) at miere production of Lehar’s The Merry Widow, with a welcoming wine and cheese party. Frederica von Stade and Placido Domingo, under Sir Saturday evening the opera was Offenbach’s Tales Andrew Davis, in a new English translation. The oper- of Hoffmann. This was a lavish (though not new) pro- etta was, understandably, sold out, and so the only tick- duction with sumptuous costumes, sets descending to ets available were seats in the Family Circle (at the very reappear later, and magical special effects. -

Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation

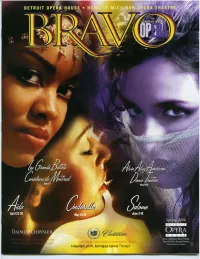

2006 Spring Opera Season is sponsored by Cadillac Copyright 2010, Michigan Opera Theatre LaSalle Bank salutes those who make the arts a part of our lives. Personal Banking· Commercial Banking· Wealth Management Making more possible LaSalle Bank ABN AMRO ~ www. la sal lebank.com t:.I Wealth Management is a division of LaSalle Bank, NA Copyright 2010,i'ENm Michigan © 2005 LaSalle Opera Bank NTheatre.A. Member FDIC. Equal Opportunity Lender. 2006 The Official MagaZine of the Detroit Opera House BRAVO IS A MICHI GAN OPERA THEAT RE P UB LI CATION Sprin",,---~ CONTRI BUTORS Dr. David DiChiera Karen VanderKloot DiChiera eason Roberto Mauro Michigan Opera Theatre Staff Dave Blackburn, Editor -wELCOME P UBLISHER Letter from Dr. D avid DiChiera ...... .. ..... ...... 4 Live Publishing Company Frank Cucciarre, Design and Art Direction ON STAGE Bli nk Concept &: Design, Inc. Production LES GRAND BALLETS CANADIENS de MONTREAL .. 7 Chuck Rosenberg, Copy Editor Be Moved! Differently . ............................... ... 8 Toby Faber, Director of Advertising Sales Physicians' service provided by Henry Ford AIDA ............... ..... ...... ... .. ... .. .... 11 Medical Center. Setting ................ .. .. .................. .... 12 Aida and the Detroit Opera House . ..... ... ... 14 Pepsi-Cola is the official soft drink and juice provider for the Detroit Opera House. C INDERELLA ...... ....... ... ......... ..... .... 15 Cadillac Coffee is the official coffee of the Detroit Setting . ......... ....... ....... ... .. .. 16 Opera House. Steinway is the official piano of the Detroit Opera ALVIN AILEY AMERICAN DANCE THEATER .. ..... 17 House and Michigan Opera Theatre. Steinway All About Ailey. 18 pianos are provided by Hammell Music, exclusive representative for Steinway and Sons in Michigan. SALOME ........ ... ......... .. ... ... 23 President Tuxedo is the official provider of Setting ............. .. ..... .......... ..... 24 formal wear for the Detroit Opera House.