Space and Lunar Surface Travel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China's Shiyan Weixing Satellite Programme, 2014-2017

SPACE CHRONICLE A BRITISH INTERPLANETARY SOCIETY PUBLICATION Vol. 71 No.1 2018 MONUMENTAL STATUES TO LOCAL LIVING COSMONAUTS CHINA’S SHIYAN WEIXING SPEKTR AND RUSSIAN SPACE SCIENCE SATELLITE PROGRAMME FIRST PICTURES OF EARTH FROM A SOVIET SPACECRAFT REPORTING THE RIGHT STUFF? Press in Moscow During the Space Race SINO-RUSSIAN ISSUE ISBN 978-0-9567382-2-6 JANUARY 20181 Submitting papers to From the editor SPACE CHRONICLE DURING THE WEEKEND of June 3rd and 4th 2017, the 37th annual Sino- Chinese Technical Forum was held at the Society’s Headquarters in London. Space Chronicle welcomes the submission Since 1980 this gathering has grown to be one of the most popular events in the for publication of technical articles of general BIS calendar and this year was no exception. The 2017 programme included no interest, historical contributions and reviews less than 17 papers covering a wide variety of topics, including the first Rex Hall in space science and technology, astronautics Memorial Lecture given by SpaceFlight Editor David Baker and the inaugural Oleg and related fields. Sokolov Memorial Paper presented by cosmonaut Anatoli Artsebarsky. GUIDELINES FOR AUTHORS Following each year’s Forum, a number of papers are selected for inclusion in a special edition of Space Chronicle. In this issue, four such papers are presented ■ As concise as the content allows – together with an associated paper that was not part the original agenda. typically 5,000 to 6,000 words. Shorter papers will also be considered. Longer The first paper, Spektr and Russian Space Science by Brian Harvey, describes the papers will only be considered in Spektr R Radio Astron radio observatory – Russia’s flagship space science project. -

Space History: State of the Art ~

SECTION VI SPACE HISTORY: STATE OF THE ART ~ INTRODUCTION hat is the current state of space history as the 21st century commences Wand the Space Age reaches its 50th anniversary? Is it a vibrant marketplace of ideas and stimulating perspectives? Is it a moribund backwater of historical inquiry with little of interest to anyone and nothing to offer the wider historical discipline? As the four essays in this section demonstrate, space history is at neither extreme of this dichotomy. It has been energized in the last quarter century by a constant stream of new practitioners and a plethora of new ideas and points of view. A fundamental professionalization of the discipline has brought to fruition a dazzling array of sophisticated studies on all manner of topics in the history of spaceflight.Y et, as the collective authors of the section argue, there is much more to be done, and each offers suggestions for how historians might approach the field in new and different ways, each enriching what already exists. This section opens with an essay by Asif A. Siddiqi assessing the state of U.S. space history. He asserts that scholars have concentrated their work in one of four subfields that collectively may be viewed as making up the whole. As Siddiqi writes, “Some saw the space program as indicative of Americans’ ‘natural’ urge to explore the frontier; some believed that the space program was a surrogate for a larger struggle between good and evil; others wrote of a space program whose main force was modern American technology; and oth- ers described a space program whose central actors were hero astronauts, rep- resenting all that was noble in American culture.” He notes that space history started as a nonprofessional activity undertaken by practitioners and enthu- siasts, always viewing the field from the top down and producing an excep- tionally “Whiggish” perspective on the past. -

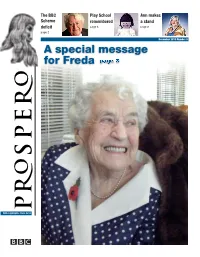

A Special Message for Freda Page 3

The BBC Play School Ann makes Scheme remembered a stand deficit page 6 page 8 page 2 December 2010 Number 9 A special message for Freda page 3 With highlights from Ariel BBC Pensions How big is & why do we have Throughout the debate over the proposed pension scheme changes, they’ve been the two questions that just won’t go away. Here Jeremy PROSPERO Peat, chairman of the Pension Fund Trustees, explains the complex December 2010 process necessary for a full valuation of the Scheme. many members the Scheme has and whether What is the valuation there is any change in the life expectancy of Prospero is provided free to members since the last valuation. But we can’t about? do some of the calculations until the retired BBC employees. It can consultation on the BBC’s pension proposals We are legally obliged to have a full actuarial ends and the way forward is clear. Agreeing all also be sent to spouses or valuation of the Pension Fund at least once the relevant details after that will take some time. dependants who want to keep every three years to help ensure that the Scheme has ‘sufficient and appropriate assets to cover its in touch with the BBC. liabilities’. This involves reviewing the Scheme’s The importance of the It includes news about financial position, to determine the appropriate level of contributions for the years ahead. assumptions former colleagues, pension Assumptions need to be made about uncertain issues, and developments at When will we know the future events such as the effect of inflation, the BBC. -

The Literature of Aeronautics, Astronautics, and Air Power

THE LITERATURE OF AERONAUTICS, ASTRONAUTICS, AND AIR POWER Richard P Hallion Air Force Flight Test Center OFFICE OF AIR FORCE HISTORY UNITED STATES AIR FORCE WASHINGTON, D.C. 1984 r ~ ~ THE LITERATURE OF AERONAUTICS, ASTRONAUTICS, AND AIR POWER Richard P. Hallion Air Force Flight Test Center THIS DOCUMENT CONTAINED BLANK PAGES THAT HAVE BEEN DELETED OFFICE OF AIR FORCE HISTORY UNITED STATES AIR FORCE WASHINGTON, D.C. 1984 c900O e%003L4 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Hallion, Richard. The Literature of Aeronautics, Astronautics, and Air Power. (USAF warrior studies) 1. Aeronautics. Military-Bibliography. 2. Air powcr-Bihliography. 3. Astronautics. Mili- tary-Bibliography. 1. United States. Air Forcec. Offie of Air Force History. If. Title. Z6724.A25H34 1984 (UG63Oi 016.3584 84-2322 ISBN 0-912799-14-5 Project Warrior Studies are published by the Office of Air Force History. The author is responsible for the scholarly judgments expressed herein, and his views should not be construed to be the official position of the United States Air Force or the Department of Defense. For sale by the Supernftendent of Documents. U.S. GoverrnmenPrinting Office Washington. D.C. 20402 iv USAF WARRIOR STUDIES Richard H. Kohn and Joseph P. Harahan General Editors Foreword The publication of The Literature of Aeronautics, Astronautics, and Air Power is part of a continuing series of historical studies from the Office of Air Force History in support of Project Warrior. Project Warrior seeks to create and maintain within the Air Force an environment where Air Force people at all levels can learn from the past and apply the warfighting experiences of past generations to the present. -

Attenborough at 90 Page 2

The newspaper for BBC pensioners Attenborough at 90 Page 2 June 2016 • Issue 3 Reporting on Life before Apollo 13 the referendum Auntie remembered Page 3 Page 6 Page 8 NEWS • MEMORIES • CLASSIFIEDS • YOUR LETTERS • OBITUARIES • CROSPERO 02 BACK AT THE BBC Attenborough at 90 Bringing back Teamwork, collaboration and the Natural History Unit some sunshine Victoria Cowan, To mark his 90th birthday, Ariel spoke to the legendary broadcaster. Senior Media Manager, Archives, talks to Ariel about two precious comic discoveries. Previously missing recordings of The Morecambe and Wise Show and The Frankie Howerd Show – both broadcast 50 years ago on the Light Programme – have recently been recovered. The items were on reel-to-reel tapes owned by listener Ken Newberry who offered a whole list of items that he had recorded in the 1960s and 70s. Victoria said: ‘Mr Newberry contacted us Sunday 24 July 1966, one week before through audience services and we asked The World Cup Final. him to send his material through. Ninety- Victoria explained that archiving policy nine per cent of what he offered us we was very different in the 1960s: ‘Back then, either already had or the information about it it was very, very selective, especially for was so vague we could not tell what it was. things like comedy. It wasn’t perceived as We can only take in material we know for important and was also quite expensive and sure we definitely broadcast. difficult to capture. The thinking then was ‘Even if we don’t have something in that it would not hold much future interest.’ our archive we have to decide whether to Victoria said she found listening to ir David Attenborough’s back It is this teamwork which has been a vital commit the time and resource to bringing the tapes ‘intriguing’ although confessed catalogue looks like a greatest ingredient in producing the consistently it in. -

Issue #94 of the Lunar and Planetary

CCONTENTSONTENTS 34th34th LPSCLPSC inin ReviewReview NewsNews fromfrom SpaceSpace SpotlightSpotlight onon EducationEducation MeetingMeeting HighlightsHighlights MilestonesMilestones NewNew and and Noteworthy Noteworthy CalendarCalendar PPreviousrevious IssuesIssues LUNAR AND PLANETARY INFORMATION BULLETIN 1 3434THTH LPSCLPSC ININ RREVIEWEVIEW SETTING NEW ATTENDANCE RECORDS IN 2003 The 34th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC) marked yet another 34th LPSC at a Glance record-breaking year, with 1179 participants from 25 countries attending the conference held at the South Shore Harbour Resort and Conference Center in Total number of attendees: 1179 League City, Texas, on March 17–21, 2003. This year’s attendance statistics Graduate student attendees: 241 (see inset) reflect NASA’s commitment to education, as well as a positive outlook Undergraduate student attendees: 70 for the future health of planetary science, as more than 25% of participants were Abstracts received: 1132 graduate or undergraduate students. Abstracts accepted: 1105 LPSC has long been recognized among the international science community as the Oral presentations: 448 most important planetary conference in the world, and this year’s meeting was no Poster presentations: 516 exception. Hundreds of planetary scientists attended both oral and poster sessions focusing on such diverse topics as meteorites; the Moon, Mars, Mercury, and Venus; impacts; outer planets and satellites; comets, asteroids, and other small bodies; interplanetary dust particles; origins of planetary systems; planetary formation and early evolution; astrobiology; and education and public outreach. Sunday night’s registration and reception were held at the Center for Advanced Space Studies, which houses the Lunar and Planetary Institute. Sunday night’s events also featured an open house for the display of education and public outreach activities and programs. -

The Moonlandings

The Moonlandings An Eyewitness Account reginald turnill Foreword by Dr Buzz Aldrin published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org © Reginald Turnill 2003 Foreword © Buzz Aldrin 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Trump Medieval 9.5/15 pt System QuarkXPress™ [se] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Turnill, Reginald. The moonlandings : an eye witness account / Reginald Turnill. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0 521 81595 9 1. Project Apollo (U.S.) 2. Space flight to the moon–History. I. Title. TL789.8.U6 A5844 2002 629.45Ј4Ј0973–dc21 2002023374 ISBN 0 521 81595 9 hardback Contents Foreword dr buzz aldrin page ix Growing Up with Space – Sources and Acknowledgments xiii 1 The Context: A Twentieth-century Faust 1 2 Preparing for Manned Spaceflight 14 3 Gagarin Puts -

97 Reg Turnill.Pdf

4 10 August 18, 2010 KM Extra (FE) ontest brings out best story writers AN APPEAL for entries for a in total from which we will short- festival is being held from Sep- writing competition with a £1,000 list five in the junior category tember 17 to 19. prize has had a good respons and five in the senior. Penguin Books, which i The short story contest is “We were concerned about the ebrating its 75th anniver: organised by the HG Wells Fes- lack of junior entries but now we has donated boxed sets of tival, which is being held in have had quite a few, some from published works of Wells as Folkestone for the second year children as young as nine. prizes for the festival. running. “Some are really very good. It is The weekend focuses on books After the deadline for entries extraordinary what good quality written by Wells when he lived was extended, more have been they are from such young writ- in the area. submitted. er Highlights include a dinner, a Reg Turnill, of the festival com- Mr Turnill has donated £1,000 history walk and art show. mittee, said: “It is now going very as the prize for the junior win- It will be opened by HG Wells’ well. ner. The senior winner will get great-great-grandson Alex “We have had around 30 entries £250 from The Grand, where the Wells. Reg Turnill at the launch of HG Wells Festival and short story HG Wells Titles by the late author HG Wells competition Picture: Gary BrownePD1555135 \ugust 13, 2010 9 , ary Glitter KING Henry VIII would probably have felt at home seeing children from Folkestone taking a step back in time at a Tudor festival 't be served’ in Dover. -

SATURN V Charles First in a Kohlhase New Series Space Milestones to Explorer the Moon

Spaceflight A British Interplanetary Society Publication Also in this issue GEOsats in peril th 50anniversary of Falcon HEAVY SATURN V Charles First in a Kohlhase new series space Milestones to explorer the Moon Vol 59 No 11 November 2017 £4.50 www.bis-space.com CONTENTS Editor: Published by the British Interplanetary Society David Baker, PhD, BSc, FBIS, FRHS Sub-editor: Volume 59 No. 11 November 2017 Ann Page Production Assistant: 411 Sizing launch vehicles Ben Jones Superlatives reign supreme when manufacturers and launch vehicle providers speak of their rockets but just what are the parameters that Spaceflight Promotion: define, small, medium, heavy or super-heavy rockets? FACTCHECKER Gillian Norman answers that question and asks just how do the claims add up? Spaceflight Arthur C. Clarke House, 27/29 South Lambeth Road, 412-415 Countdown to Falcon Heavy London, SW8 1SZ, England. SpaceX is getting set to fly its super-heavy rocket, as audacious in its Tel: +44 (0)20 7735 3160 goal as anything launched to date by this entrepreneurial company. We Fax: +44 (0)20 7582 7167 assess the challenge and the risk and rate it against competitors as Elon Email: [email protected] Musk boasts bold new objectives. www.bis-space.com ADVERTISING 416-423 Thunder at the Cape Tel: +44 (0)1424 883401 Fifty years ago, in November 1967, Email: [email protected] NASA took a giant leap forward with DISTRIBUTION the launch of the world’s biggest Spaceflight may be received worldwide by mail through membership of the British rocket, the Saturn V. -

A Space Policy

House of Commons Science and Technology Committee 2007: A Space Policy Seventh Report of Session 2006–07 Volume I Report, together with formal minutes Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 4 July 2007 HC 66-I Published on 17 July 2007 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Science and Technology Committee The Science and Technology Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Office of Science and Innovation and its associated public bodies. Current membership Mr Phil Willis MP (Liberal Democrat, Harrogate and Knaresborough)(Chairman) Adam Afriyie MP (Conservative, Windsor) Mrs Nadine Dorries MP (Conservative, Mid Bedfordshire) Mr Robert Flello MP (Labour, Stoke-on-Trent South) Linda Gilroy MP (Labour, Plymouth Sutton) Dr Evan Harris MP (Liberal Democrat, Oxford West & Abingdon) Dr Brian Iddon MP (Labour, Bolton South East) Chris Mole MP (Labour/Co-op, Ipswich) Dr Bob Spink MP (Conservative, Castle Point) Graham Stringer MP (Labour, Manchester, Blackley) Dr Desmond Turner MP (Labour, Brighton Kemptown) Previous Members of the Committee during the inquiry Mr Brooks Newmark MP (Conservative, Braintree) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental Select Committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No.152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at www.parliament.uk/s&tcom A list of Reports from the Committee in this Parliament is included at the back of this volume.