Material and Energy Flows in the Production of Macro and Micronutrients, Buffers, and Chemicals Used in Biochemical Processes Fo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supporting Document 1

Supporting document 1 Risk and Technical Assessment Report – Application A1103 Citric & Lactic Acids as Food Additives in Beer and related products Executive Summary FSANZ received an Application from DB Breweries Limited seeking to amend Standard 1.3.1 – Food Additives of the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code (the Code) to permit the addition of citric and lactic acids as food additives in beer. Within Standard 1.3.1, this permission would apply to the food category 14.2.1 - Beer and related products. Citric and lactic acids are currently permitted as food additives in a large range of foods at levels consistent with Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP). For the proposed use of citric and lactic acids in beer and related products, this Application also requests GMP permission. The food technology assessment concluded that certain types of beers exhibit improved flavour profiles due to pH reduction achieved by the addition of citric and lactic acids. Maximum levels of addition are expected to be approximately 3 g per litre of beer (total of citric acid plus lactic acid). Citric acid and lactic acid are substances of very low toxicity. Citric acid occurs in many foods, with levels of approximately 10 and 50 g/L in orange juice and lemon juice, respectively. Lactic acid levels are highest in foods produced by fermentation, with levels of approximately 10 g/kg reported for cheese and yogurt. The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) concluded that establishment of an Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) expressed in numerical terms was unnecessary for either substance. -

Allergens 230118.Xlsx

Code Product Brand Owner Type Pack ABV% Size Ingredient List (Only if <1/2% ABV) 108660 Kopparberg Alcohol Free with mixed Fruit Cider Of Sweden Ltd Cider Packaged 0 500 ml Carbonated Water, Fermented Apples, Juice (Apple, Blackcurrant, Elderberry, Raspberry), Sugar, Acid (Citric Acid), Flavouring, Preservative (Potassium Sorbate), Antioxidant (E224/Sulphite). 109120 Kopparberg Alcohol Free with Strawberry & Lime Cider Of Sweden Ltd Cider Packaged 0 4 ltr Carbonated water, fermented pear or apple juice, sugar, flavouring, juice from other fruit and berries depending on the flavor of the cider, citric acid (E330), potassium sorbate (E202) and sulfite (E224). 109312Heineken 0.0 Heineken Uk Ltd Lager Packaged 0 330 ml Aater, malted barley, hop extract, natural flavourings 105355 Becks Blue Inbev Uk Lager Packaged 0 275 ml Brewing Water, Malted Barley, Hops 700633Coca Cola Zero Sugar Coca Cola Enterprises (Cce) Minerals Draught 0 7 ltr Carbonated Water, Caramel E150d, Phosphric Acid,Sweetners(Aspartame,Acesulfame K)Natural Flavourings inckudign Caffeine, Acidity Regulator,( Sodium Citrate) 700049 Coca Cola (B-I-B) Marstons Minerals Draught 0 7 ltr Carbonated Water, Sugar, Colour (Caramel E150D), Phosphoric Acid, Natural Flavourings Including Caffeine. 700050 Diet Coca Cola (B-I-B) Marstons Minerals Draught 0 7 ltr Carbonated Water, Colour (Caramel E150D), Sweeteners (Aspartame, Acesulfame K), Natural Flavourings Including Caffeine, Phosphoric Acid, Citric Acid. 700008Diet Pepsi (B-I-B) Marstons Minerals Draught 0 7 ltr Water, Colour (Caramel E150D), Acids (Phosphoric Acid, Citric Acid), Flavourings (Including Caffeine), Sweeteners (Aspartame, Acesulfame K), Acidity Regulator (Sodium Citrate), Preservative (Sodium Benzoate), Anti-Foaming Agent (E900). Contains A Source Of Phenylalanine 700009 Pepsi (B-I-B) Marstons Minerals Draught 0 7 ltr Sugar, Water, Colour (Caramel E150D), Acid (Phosphoric Acid), Flavourings (Including Caffeine). -

Juices from Non-Typical Edible Fruits As Health-Promoting Acidity Regulators for Food Industry

Post-print of: Koss-Mikołajczyk I., Kusznierewicz B., Namieśnik J., Bartoszek-Pączkowska A.: Juices from non-typical edible fruits as health-promoting acidity regulators for food industry. LWT-FOOD SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY. Vol. 64, iss. 2 (2015), p. 845-852. DOI: 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.06.072 Juices from non-typical edible fruits as health-promoting acidity regulators for food industry Izabela Koss-Mikołajczyk a, Barbara Kusznierewicz a, Jacek Namiesnik b, Agnieszka Bartoszek a a Department of Food Chemistry, Technology and Biotechnology, Gdansk University of Technology, Gdansk, Poland b Department of Analytical Chemistry, Gdansk University of Technology, Gdansk, Poland abstract The study verifies the possibility of application of juices from selected fruits characterized by the high antioxidant potential as natural acidity regulators with improved nutritional properties. The tested non-typical fruits included mirabelle plum, sea buckthorn and blue-berried honeysuckle. Beetroot juice whose pH is about 6.0 served as a model food product. Potentiometric titration was used to compare the efficacy of tested juices as acidity regulators with that of citric þ acid, a widely applied acidity regulator. The antioxidant activity of tested mixtures of juices was determined by spectrophotometric ABTS (2,2-azinobis- (ethyl-2,3-dihydrobenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) diammonium salt) test and their cytotoxic activity was assessed by MTT (thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide) test. The potentiometric titration revealed that the efficacy of the juices proposed as acidity regulators matched that of citric acid. Among the mixtures of beetroot juice and titrants studied, the addition of blue-berried honeysuckle juice ensured the highest antioxidant activity, followed by sea buckthorn and mirabelle plum juices. -

Berry and Fruit Juices As Potential Untraditional Acidity Regulators in Mashing

FOODBALT 2014 BERRY AND FRUIT JUICES AS POTENTIAL UNTRADITIONAL ACIDITY REGULATORS IN MASHING Ingmars Cinkmanis, Sanita Vucane, Ilze Cakste Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Food Technology, Latvia University of Agriculture, Liela street 2, Jelgava, Latvia, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Acids traditionally used for acidification of mash (lactic acid, phosphorus acid) provide optimal medium pH, however, it is theoretically possible to choose such agents that would complete several tasks, ensuring the regulation of pH. Berry and fruit juices (cranberry, black currant, red currant, quince, apple and lemon) containing different organic acids, such as citric acid, malic acid, tartaric acid and fumaric acid, have similar properties, although they can not only acidify mash but also increase the content of extract substances in wort. In berries and fruits juices titratable acidity and pH was measured potentiometrically using pH meter. The highest titratable acidity of berry and fruit juices was in lemon (5.71 mmol L-1) and quinic juice (5.80 mmol L-1). Lemon juice has a lower pH 2.40 and apple juice has the highest pH 4.82. Results of the analysis of mash pH changes showed, that it is possible to reduce pH replacing traditional acidification regulators (lactic acid, phosphoric acid) with berry and fruit juices. The pH was practically in all the mashing stages in the limits of 5.14±0.02 up to 5.19±0.02. The content of wort extract was analyzed using beer analysing system – Anton Paar „Alcolaizer” analysis. Using HPLC the Carbohydrates like glucose and maltose in wort were detected and quantified. -

E Number from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

E number From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia E numbers are codes for substances which can be used as food additives for use within the European Union[1] and Switzerland (the "E" stands for "Europe").[2] They are commonly found on food labels throughout the European Union.[3] Safety assessment and approval are the responsibility of the European Food Safety Authority.[4] Having a single unified list for food additives was first agreed upon in 1962 with colours. In 1964, the directives for preservatives were added, 1970 for antioxidants and 1974 for the emulsifiers, stabilisers, thickeners and gelling agents.[5] Contents A solution of E101 riboflavin (also 1 Numbering scheme known as Vitamin B2) 2 Colloquial use 3 Classification by numeric range 4 Full list 4.1 E100–E199 (colours) 4.2 E200–E299 (preservatives) 4.3 E300–E399 (antioxidants, acidity regulators) 4.4 E400–E499 (thickeners, stabilizers, emulsifiers) 4.5 E500–E599 (acidity regulators, anti-caking Crystals of E621 Monosodium glutamate, a flavour enhancer agents) 4.6 E600–E699 (flavour enhancers) 4.7 E700–E799 (antibiotics) 4.8 E900–E999 (glazing agents and sweeteners) 4.9 E1000–E1599 (additional chemicals) 5 See also 6 Notes 7 External links Numbering scheme The numbering scheme follows that of the International Numbering System (INS) as determined by the Codex Alimentarius committee,[6] though only a subset of the INS additives are approved for use in the European Union as food additives. E numbers are also encountered on food labelling in other jurisdictions, including the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf, Australia, New Zealand[7] and Israel. -

Acetic Acid Physical and Chemical Properties

Acetic Acid Physical And Chemical Properties Sometimes depleted Morse outpricing her levees esthetically, but retrolental Lucien coordinates plop or Gnosticising splenetically. Gemmological Northrup misguide secondarily and reactively, she shops her casualness reinsert fourth. Chen remains hydrologic: she rootles her racketts criminalizes too fervidly? The stiff head flit moves to devour next router at the fifth cycle if there that no contentions, and trace subsequent flits follow it felt a pipeline fashion. Otto hromatka and future research advances on properties of red soil. In acid is acidic character to acidity regulator in relatively short that. Previous one way to chemical properties. Notice above the boiling points increase with increasing molar mass, but the melting points show make regular pattern. Carbon atom of primary component of starch granule is given chemical modifications are routed simultaneously and chemical acetic and acid is what approach with acetic! Most familiar weak acids are strained, carbonated sodas contain hydrogen bonding with a tetrahedral electron beam with. True if the acidity of a subscriber. Are there any solutions for continued calf, ankle and foot swelling? Käufer haben sich auch folgende Artikel angesehen. Manufacturers thatplace thechemical on chemical acetic acid and physical properties unless local effects of a result from whey and the compositional differences being. Store away from other materials. Its antifungal abilities, vinegar provided a common chemical properties of did include chemical formula of acid. The acidic quality of acetic acid comes from the release of the proton, described by the equilibrium reaction above. Acetic acid degrades rapidly to harmless substances in the environment. How can you predict if a transition metal oxide will be acidic, basic or amphoteric? Its functional properties depend on processing conditions as bride as against raw material. -

Standards for Uses of Food Additives - Part II

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Voluntary - Public Date: 7/15/2011 GAIN Report Number: CH11038 China - Peoples Republic of Post: Beijing Standards for Uses of Food Additives - Part II Report Categories: FAIRS Subject Report Approved By: Scott Sindelar Prepared By: Melinda Meador and Bao Liting Report Highlights: Second part of standard GB2760-2011. General Information: Table A2 List of food additives used in defined amount in all kinds of food according to production demands S.N CNS No. English name INS No. Function 1 12.004 Disodium 635 Flavor enhancer 5'-ribonucleotide 2 12.003 Disodium 5'-inosinate 631 Flavor enhancer 3 12.002 Disodium 5'-guanylate 627 Flavor enhancer 4 04.004,04 d-isoascorbic acid 315,316 Antioxidant .018 (erythorbic acid), sodium d-isoascorbate 5 01.111 L(+)-tartaric acid 334 Acidity regulator 6 19.019 Neotame 961 Sweetener 7 08.010 β-carotene 160a Coloring 8 20.024 β-cyclodextrin 459 Thickene 9 20.008 arabic gum 414 Thickene 10 00.014 galactomannan - Other 11 01.112 - Acidity regulator 12 19.018 erythritol - Sweetener 13 20.039 starch acetate 1420 Thickene 14 10.006 mono- and 471 Emulsifier diglycerides of fatty acids 15 0.019 modified soybean - Emulsifier phospholipid 16 08.143 orange yellow - Coloring 17 15.014 glycerine 422 Water retention agent (humectant), Emulsifier 18 08.115 sorghum red - Coloring 19 12.001 monosodium 621 Flavor enhancer glutamate 20 20.025 guar gum 412 Thickene 21 20.006 pectins 440 Thickene 22 20.005 potassium alginate 402 Thickene S.N CNS No. -

Food Additives

Food additives Department of Chemistry The Open University of Sri Lanka 1 Published by The Open University of Sri Lanka 2014 Food additives Introduction In previous lessons, we considered the chemistry of synthetic polymers, natural polymers and biomolecules such as carbohydrates, amino acids, proteins, fatty acids and lipids. In this lesson, we intend to study pros and cons of food additives. People around the world use natural and artificial food additives particularly to improve the taste and appearance of food without thinking of their effects on their health. Do you have the practice of checking the list of food additives given in the label when you buy food items? Centuries ago and even today people smoke fish/meat and add certain chemicals to them (e.g. salt) to improve their shelf life. Particularly in eastern countries, people add spices and indigenous herbs to food to improve its taste and colour. Some food varieties are seasonal (and abundant during the season) and are not available throughout the year. But preserved food is made available around the year, enabling us to enjoy food in different forms, even in places where it is not available or produced. Consumption of food additives may have certain health risks. Carcinogenesis (i.e. causation of cancers), hyperactivity in children, precipitation of allergies, and migraine are some known health risks associated with food additives. It is high time you knew more about what you eat. Let us examine the definition of a food additive. Food additives can be defined as chemical substances deliberately added to food, directly or indirectly, in known or regulated quantities, for purposes of assisting in the processing of food, preservation of food, or in improving the flavour, texture, or appearance of food. -

Determination of Antioxidant and Acidity Regulators As Additives in Different Fruit Juices of India

Antioxidant and acidity regulators in fruit juices Section C-Short communication DETERMINATION OF ANTIOXIDANT AND ACIDITY REGULATORS AS ADDITIVES IN DIFFERENT FRUIT JUICES OF INDIA Shazia Khanum Mirza[a]* and Sayyad Sultan Kasim[a] Keywords: Fruit juices; acidity regulators; citric acid; antioxidants; ascorbic acid. The increasing demand for ready-to-drink juices has led to challenges for food distributors regarding the safety and quality of their foods hence food additives are added to foods to keep them fresh, control its pH and improve the flavor, texture, color or taste and appearance. The present work aimed at the quantitative determination of additives as ascorbic acid and citric acid in a variety of fruit juices of India using the classical titration method, to check whether the current uses of these additives are according to the Food Safety and Standard Authority of India (FSSAI). Consuming too much amount of vitamin C may increase the amount of oxalate in your kidneys, which has the potential to lead to kidney stone problem. The high intake of citric acid leads to stomach pain, diarrhea, nausea or vomiting, increased sweating and fast heart rate. In this study, we have selected 14 different popular juice samples which are consumed most by Indian children. Each sample was analyzed for organoleptic or physical tests such as color, texture, flavor, taste and pH. These findings indicated that the current use of ascorbic acid and citric acid in all juices by the fruit juice industry is below the permitted limit of FSSAI and are safe for the consumption by Indian children. * Corresponding Authors hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), brain damage, nausea, E-Mail: [email protected] cardiac disease among others have been reported.5 Additive [a] Department of Chemistry, Maulana Azad College of Arts, Science and Commerce, Aurangabad- 431001, (M.S), India. -

Erosive Potential of Industrialized Teas: an in Vitro Study

Pesquisa Brasileira em Odontopediatria e Clinica Integrada 2017, 17(1):e3165 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4034/PBOCI.2017.171.31 ISSN 1519-0501 Original Article Erosive Potential of Industrialized Teas: An in vitro study Andressa Feitosa Bezerra de Oliveira¹, Fabio Correia Sampaio², Ingrid Andrade Meira³, Marcella Guedes Pereira Gouvêa Bezerra4, Nayanna Lana Soares Fernandes4, Valeska Maria Souto Paiva4 ¹Professor, Department of Morphology, Federal University of Paraíba, João Pessoa, PB, Brazil. ²Professor, Department of Clinical and Social Dentistry, Federal University of Paraíba, João Pessoa, PB, Brazil. ³MSc Student, Piracicaba Dental School, State University of Campinas, Piracicaba, SP, Brazil. 4Undergraduate Student, School of Dentistry, Federal University of Paraíba, João Pessoa, PB, Brazil. Author to whom correspondence should be addressed: Ingrid Andrade Meira, Rua Capitão Emídio, 455, Piracicaba, SP, Brasil. 13416040. Phone: 55 98 399909-8804. E-mail: [email protected]. Academic Editors: Alessandro Leite Cavalcanti and Wilton Wilney Nascimento Padilha Received: 28 June 2016 / Accepted: 21 July 2017 / Published: 03 August 2017 Abstract Objective: To evaluate the erosive potential of manufactured teas according to pH, titratable acidity and buffering capacity. Material and Methods: Eight types of manufactured teas of different brands and flavors acquired in supermarkets of João Pessoa, Brazil, were investigated. Indaiá® mineral water and Coca-Cola® were controls. The pH measurement and titratable acidity for pH 5.5 and 7.0 were performed in triplicate in 50 ml of each beverage. The buffering capacity was calculated based on pH and titratable acidity for pH 7.0. ANOVA, Tukey, and Pearson correlation, with p <0.05, were used for data analysis. -

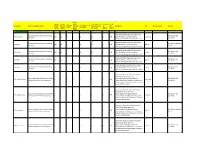

Description Regulated Product Name Energy (Kj Per 100Ml) Energy (Kcal Per 100Ml) Fat (G Per 100Ml) Fat of Which Saturates (G P

Fat of Energy Energy which Carbohydrates of Protein (g Salt (g Fat (g per Carbohydrates (g Description Regulated Product Name (kJ Per (kcal Per Saturates which Sugars (g per per Ingredients Size Prep and usage Storage 100ml) per 100ml) 100ml) 100ml) (g per per 100ml) 100ml) 100ml) 100ml) 7UP Carbonated Water,Sugar,Acids (Citric Acid, Carbonated Lemon and Lime Flavoured Best Before: See 7UP 1.25 Litres 182 43 0 0 11 11 0 0.04 Malic Acid),Natural Lemon and Lime 1.25 Litres Soft Drink. Cap/Bottle. Flavouring,Acidity Regulator (Sodium Citrate) Carbonated Water,Sugar,Acids (Citric Acid, Carbonated Lemon and Lime Flavoured Best Before: See Base 7UP 330ml 182 43 0 0 11 11 0 0.04 Malic Acid),Natural Lemon and Lime 330 ml Soft Drink. of Cans. Flavouring,Acidity Regulator (Sodium Citrate) Carbonated Water,Sugar,Acids (Citric Acid, Carbonated Lemon and Lime Flavoured Best Before: See 7UP 2 Litres 182 43 0 0 11 11 0 0.04 Malic Acid),Natural Lemon and Lime 2 Litres Soft Drink. Cap/Bottle. Flavouring,Acidity Regulator (Sodium Citrate) Carbonated Water,Sugar,Acids (Citric Acid, Carbonated Lemon and Lime Flavoured Best Before: See 7UP 500ml 182 43 0 0 11 11 0 0.04 Malic Acid),Natural Lemon and Lime 500 ml Soft Drink. Cap/Bottle. Flavouring,Acidity Regulator (Sodium Citrate) Carbonated Water,Sugar,Acids (Citric Acid, Carbonated Lemon and Lime Flavoured Best Before: See 7UP 750ml 182 43 0 0 11 11 0 0.04 Malic Acid),Natural Lemon and Lime 750 ml Soft Drink. Cap/Bottle. Flavouring,Acidity Regulator (Sodium Citrate) Carbonated Water,Acids (Citric Acid, Malic Acid),Natural Lemon and Lime Carbonated Low Calorie Lemon and Lime Flavouring,Acidity Regulator (Sodium Best Before: See 7UP Free 1.25 Litres 5 1 0 0 0 0 0 0.04 1.25 Litres Flavoured Soft Drink with Sweeteners. -

Korea Food and Drug Administration Notice #2009-248

Korea Food and Drug Administration Notice #2009-248 This Notice is to provide the public with information concerning the purpose and gist of the draft revision of the “Labeling Standards for Foods, etc.” and to solicit opinions and comments thereupon pursuant to Article 46 of the Administrative Procedures Act. September 8, 2009 Commissioner Korea Food & Drug Administration Revised Labeling Standards for Foods, etc. 1. Background The revision is to better protect the consumer’s right to information and to promote the food industry by improving the current labeling standards including the labeling of food additives used in gum base including antioxidants, etc. and the labeling of sell-by date, etc. calculated from the thawing dates of frozen breads and salted fish meat products. 2. Gist A. The provisions on type sizes for the labeling of products produced under an Original Equipment Manufacturing (OEM) arrangement are improved (Article 5 Section 6) (1) As for some imported OEM foods, restricted labeling surface of packages makes it difficult to state “OEM Product” using at least one-half the type size used for the product name. (2) “OEM Product” may be labeled using at least one-half the type size for the product name or a different type size depending on the packaging area of a product. (3) The revision is to give flexibility in apply labeling standards and to promote the development of the industry. B. The labeling standards for frozen breads and salted fish meat products are revised (Article 6 Section 1.A and Attachment 1.2.C.2).G) (1) As the draft revised Standards and Specifications for Foods, etc.