Elizabeth F. Emens Aggravating Youth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Homeschooling and the Question of Socialization Revisited

Homeschooling and the Question of Socialization Revisited Richard G. Medlin Stetson University This article reviews recent research on homeschooled children’s socialization. The research indicates that homeschooling parents expect their children to respect and get along with people of diverse backgrounds, provide their children with a variety of social opportunities outside the family, and believe their children’s social skills are at least as good as those of other children. What homeschooled children think about their own social skills is less clear. Compared to children attending conventional schools, however, research suggest that they have higher quality friendships and better relationships with their parents and other adults. They are happy, optimistic, and satisfied with their lives. Their moral reasoning is at least as advanced as that of other children, and they may be more likely to act unselfishly. As adolescents, they have a strong sense of social responsibility and exhibit less emotional turmoil and problem behaviors than their peers. Those who go on to college are socially involved and open to new experiences. Adults who were homeschooled as children are civically engaged and functioning competently in every way measured so far. An alarmist view of homeschooling, therefore, is not supported by empirical research. It is suggested that future studies focus not on outcomes of socialization but on the process itself. Homeschooling, once considered a fringe movement, is now widely seen as “an acceptable alternative to conventional schooling” (Stevens, 2003, p. 90). This “normalization of homeschooling” (Stevens, 2003, p. 90) has prompted scholars to announce: “Homeschooling goes mainstream” (Gaither, 2009, p. 11) and “Homeschooling comes of age” (Lines, 2000, p. -

03-04 Dean's Report

Dean’s Report 2003 - 2004 CONTENTS 2 Carter Named Alumna of the Year DEAN BOARD OF DIRECTORS 3 Anthony A. Tarr 2002-2005 Craig Borowski ‘00 Program on Law and State ASSOCIATE DEAN FOR ACADEMIC AFFAIRS James Gilday ‘86 Government Symposium Andrew R. Klein Amy E. Hamilton ‘89 ASSOCIATE DEAN FOR GRADUATE STUDIES Scott D. Yonover ‘89 4 Jeffrey W. Grove Fall Semester Lectures 2003-2006 ASSOCIATE DEAN FOR STUDENT SERVICES Page Gifford ‘75 AND ADMISSIONS Gilbert L. Holmes ‘99 5 Angela M. Espada Linda L. Meier ‘87 Inaugural Leibman Forum Hon. Margret G. Robb ‘78 ASSOCIATE DEAN FOR TECHNOLOGY Patrick J. Schauer ‘79 Thomas Allington 8 Donald L. Simkin ‘74 Kennedy Scholars Program ASSISTANT DEAN FOR EXTERNAL AFFAIRS Hon. G. Michael Witte ‘82 Jonna M. Kane MacDougall, ’86 2004-2007 9 DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT Hon. Cynthia Ayers ‘82 Scholarship and Award Recipients Carol Neary Richard N. Bell ‘75 James Hernandez ‘85 DIRECTOR OF PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT Victor Ippoliti ‘99 16 AND PRO BONO PROGRAMS Tandra Johnson ‘98 Annual Report of Private Giving Shannon L. Williams John Maley ‘88 Tammy J. Meyer ‘89 DIRECTOR OF ADMINISTRATION AND FINANCE 17 Hon. Gary L. Miller ‘80 Jo-Ann B. Feltman Partners in Progress Mariana Richmond ‘91 Hon. Robert H. Staton ‘55 19 SCHOOL OF LAW ALUMNI ASSOCIATION Jerome Withered ‘80 John Holt 2004-2005 Sally F. Zweig ‘86 PRESIDENT 20 Robert W. Wright ’90 Dean’s Council VICE PRESIDENT Mary F. Panzi ’88 21 Law School Associates SECRETARY Nathan Feltman ’94 26 TREASURER Law Firm and Corporate Campaign Eric Riegner ’88 EXECUTIVE COUNCIL -

Child Labor Rules for Employing Youth in Restaurants and Quick-Service Establishments Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)

U.S. Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division (July 2010) Fact Sheet #2A: Child Labor Rules for Employing Youth in Restaurants and Quick-Service Establishments Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) This fact sheet provides general information concerning the application of the federal child labor provisions to restaurants and quick-service establishments that employ workers who are less than 18 years of age. For detailed information about the federal youth provisions, please read Regulations, 29 CFR Part 570. The Department of Labor is committed to helping young workers find positive, appropriate, and safe employment experiences. The child labor provisions of the FLSA were enacted to ensure that when young people work, the work does not jeopardize their health, well-being, or educational opportunities. Working youth are generally entitled to the same minimum wage and overtime protections as older adults. For information about the minimum wage and overtime e requirements in the restaurant and quick-service industries, please see Fact Sheet # 2 in this series, Restaurants and Quick Service Establishment under the Fair Labor Standards Act. Minimum Age Standards for Employment The FLSA and the child labor regulations, issued at 29 CFR Part 570, establish both hours and occupational standards for youth. Youth of any age are generally permitted to work for businesses entirely owned by their parents, except those under 16 may not be employed in mining or manufacturing and no one under 18 may be employed in any occupation the Secretary of Labor has declared to be hazardous. 18 Years Once a youth reaches 18 years of age, he or she is no longer subject to the federal of Age child labor provisions. -

Appeal from the Juvenile Court for Robertson County No

IN THE COURT OF APPEALS OF TENNESSEE AT NASHVILLE Assigned on Briefs September 10, 2002 TENNESSEE DEPARTMENT OF CHILDREN’S SERVICES v. FLORENCE HOFFMEYER, ET AL. Appeal from the Juvenile Court for Robertson County No. D-18308 Max Fagan, Judge No. M2002-00076-COA-R3-JV- Filed March 13, 2003 The natural parents of a seventeen year old girl appeal the action of the Juvenile Court of Robertson County terminating their parental rights based upon a finding of severe child abuse under Tennessee Code Annotated section 36-1-113(g)(4). Because the appellate record is incomplete, we vacate the judgment and remand the case to the trial court for further proceedings. Tenn. R. App. P. 3 Appeal as of Right; Judgment of the Juvenile Court Vacated and Remanded WILLIAM B. CAIN, J., delivered the opinion of the court, in which BEN H. CANTRELL, P.J., M.S., joined. PATRICIA J. COTTRELL, J., concurring. Mark Walker, Goodlettsville, Tennessee, for the appellant, Florence Hoffmeyer. Bryce C. Ruth, Jr., White House, Tennessee, for the appellant, Larry Hoffmeyer. Paul G. Summers, Attorney General & Reporter and Elizabeth C. Driver, Assistant Attorney General, for the appellee, State of Tennessee, Department of Children’s Services; In the Matter of: A.L.H., child under the age of 18 years. OPINION Larry and Florence Hoffmeyer, husband and wife, are parents of two children, Susan Hoffmeyer, now an adult, and A.H., born August 7, 1985. Following a hearing on November 5 and 10, 1999, upon a petition of the Department of Children’s Services for temporary custody of Susan Hoffmeyer and A.H., the Juvenile Court of Robertson County, on November 30, 1999, entered an Order providing: This cause came to be heard on the 5th and 10th days of November, 1999 before the Honorable Judge Max Fagan upon the petition of the Department of Children Services for temporary custody of SUSAN HOFFMEYER and [A.H.] (hereinafter referred to as ‘minor children’). -

Download Issue

YOUTH &POLICY No. 116 MAY 2017 Youth & Policy: The final issue? Towards a new format Editorial Group Paula Connaughton, Ruth Gilchrist, Tracey Hodgson, Tony Jeffs, Mark Smith, Jean Spence, Naomi Thompson, Tania de St Croix, Aniela Wenham, Tom Wylie. Associate Editors Priscilla Alderson, Institute of Education, London Sally Baker, The Open University Simon Bradford, Brunel University Judith Bessant, RMIT University, Australia Lesley Buckland, YMCA George Williams College Bob Coles, University of York John Holmes, Newman College, Birmingham Sue Mansfield, University of Dundee Gill Millar, South West Regional Youth Work Adviser Susan Morgan, University of Ulster Jon Ord, University College of St Mark and St John Jenny Pearce, University of Bedfordshire John Pitts, University of Bedfordshire Keith Popple, London South Bank University John Rose, Consultant Kalbir Shukra, Goldsmiths University Tony Taylor, IDYW Joyce Walker, University of Minnesota, USA Anna Whalen, Freelance Consultant Published by Youth & Policy, ‘Burnbrae’, Black Lane, Blaydon Burn, Blaydon on Tyne NE21 6DX. www.youthandpolicy.org Copyright: Youth & Policy The views expressed in the journal remain those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Editorial Group. Whilst every effort is made to check factual information, the Editorial Group is not responsible for errors in the material published in the journal. ii Youth & Policy No. 116 May 2017 About Youth & Policy Youth & Policy Journal was founded in 1982 to offer a critical space for the discussion of youth policy and youth work theory and practice. The editorial group have subsequently expanded activities to include the organisation of related conferences, research and book publication. Regular activities include the bi- annual ‘History of Community and Youth Work’ and the ‘Thinking Seriously’ conferences. -

Zero Tolerance and Exclusionary School Discipline Policies Harm Students and Contribute to the Cradle to Prison Pipeline ® the Problem: Pushing Students out of School

ISSUE BRIEF November 2012 Zero Tolerance and Exclusionary School Discipline Policies Harm Students and Contribute to the Cradle to Prison Pipeline ® The Problem: Pushing Students Out of School ut-of-school suspensions and expulsions—discipl ine Opractices that exclude children from school—have increased dramatically in the United States since the 1970s. This increase is largely due to schools’ overre - liance on “zero tolerance” policies. The Dignity in Schools Campaign describes zero tolerance as “a school discipline policy or practice that results in an automatic disciplinary consequence such as in-school or out-of-school suspension, expulsion, or involuntary school transfer for any student who commits one or more listed offenses. A school discipline policy may be a zero tolerance policy even if administrators have some discretion to modify the consequence on a case-by-case basis.” 1 Zero tolerance policies impose automatic and harsh discipline for a wide range of student infractions, s s i L including non-violent disruptive behavior, truancy, e v e dress code violations, and insubordination. Even when t S © o school policies don’t impose automatic suspensions for t o h behavior, the culture of overzealous exclusion from P school that is fostered by the zero tolerance mindset school year involved weapons or drugs, while 64% of has created a situation in which children are being suspensions were for “disobedient or disruptive behavi or,” removed from school for increasingly minor behavior truancy, or “intimidation.” 3 These policies are a issues. An October 2011 report from the National Edu - problem for all children, regardless of background or cation Policy Center found that only 5% of suspensions home-life. -

Youth Participation in Electoral Processes Handbook for Electoral Management Bodies

Youth Participation in Electoral Processes Handbook for Electoral Management Bodies FIRST EDITION: March 2017 With support of: European Commission United Nations Development Programme Global Project Joint Task Force on Electoral Assistance for Electoral Cycle Support II ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Lead authors Ruth Beeckmans Manuela Matzinger Co-autors/editors Gianpiero Catozzi Blandine Cupidon Dan Malinovich Comments and feedback Mais Al-Atiat Julie Ballington Maurizio Cacucci Hanna Cody Kundan Das Shrestha Andrés Del Castillo Aleida Ferreyra Simon Alexis Finley Beniam Gebrezghi Najia Hashemee Regev Ben Jacob Fernanda Lopes Abreu Niall McCann Rose Lynn Mutayiza Chris Murgatroyd Noëlla Richard Hugo Salamanca Kacic Jana Schuhmann Dieudonne Tshiyoyo Rana Taher Njoya Tikum Sébastien Vauzelle Mohammed Yahya Lea ZoriĆ Copyeditor Jeff Hoover Graphic desiger Adelaida Contreras Solis Disclaimer This publication is made possible thanks to the support of the UNDP Nepal Electoral Support Project (ESP), generously funded by the European Union, Norway, the United Kingdom and Denmark. The information and views set out in this publication are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the UN or any of the donors. The recommendations expressed do not necessarily represent an official UN policy on electoral or other matters as outlined in the UN Policy Directives or any other documents. Decision to adopt any recommendations and/or suggestions presented in this publication are a sovereign matter for individual states. Youth -

Youth Voter Participation

Youth Voter Participation Youth Voter Participation Involving Today’s Young in Tomorrow’s Democracy Copyright © International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) 1999 All rights reserved. Applications for permission to reproduce all or any part of this publication should be made to: Publications Officer, International IDEA, S-103 34 Stockholm, Sweden. International IDEA encourages dissemination of its work and will respond promptly to requests for permission for reproduction or translation. This is an International IDEA publication. International IDEA’s publications are not a reflection of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA’s Board or Council members. Art Direction and Design: Eduard âehovin, Slovenia Illustration: Ana Ko‰ir Pre-press: Studio Signum, Slovenia Printed and bound by: Bröderna Carlssons Boktryckeri AB, Varberg ISBN: 91-89098-31-5 Table of Contents FOREWORD 7 OVERVIEW 9 Structure of the Report 9 Definition of “Youth” 9 Acknowledgements 10 Part I WHY YOUNG PEOPLE SHOULD VOTE 11 A. Electoral Abstention as a Problem of Democracy 13 B. Why Participation of Young People is Important 13 Part II ASSESSING AND ANALYSING YOUTH TURNOUT 15 A. Measuring Turnout 17 1. Official Registers 17 2. Surveys 18 B. Youth Turnout in National Parliamentary Elections 21 1. Data Sources 21 2. The Relationship Between Age and Turnout 24 3. Cross-National Differences in Youth Turnout 27 4. Comparing First-Time and More Experienced Young Voters 28 5. Factors that May Increase Turnout 30 C. Reasons for Low Turnout and Non-Voting 31 1. Macro-Level Factors 31 2. -

Resilience Matters: Examining the School to Prison Pipeline Through the Lens of School

Glenn Justice Policy Journal, Spring, 2019 Resilience Matters: Examining the School to Prison Pipeline through the Lens of School- Based Problem Behaviors Jonathan W. Glenn1 Justice Policy Journal Volume 16, Number 1 (Spring, 2019) © Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice 2019 www.cjcj.org/jpj Abstract The school-to-prison pipeline is an expansive issue that impacts the educational and criminal justice systems in the United States. Traditionally, research has linked the prevalence of the pipeline to factors based within school systems. These systemic factors include the use of zero tolerance policies, exclusionary disciplinary practices, and the presence of school resource officers. The present study aims to explore the impact of school-based problem behaviors as a catalyst to the school- to-prison pipeline. A sample of 112 mental health professionals (MPHs) who specialize in working with youth at-risk for justice system involvement were surveyed to assess their perceptions of three theoretical predictors of problem behaviors including parental efficacy, child impulsivity, and child resilience. Results indicate that respondents perceive that child resilience predicts problem behaviors above and beyond any other theoretical predictor. The implications of this finding as well as recommendations are discussed. 1 North Carolina Central University Corresponding Author: Jonathan W. Glenn, [email protected] Resilience Matters 1 Introduction The school-to-prison pipeline refers to the process by which students are funneled from the school system into the juvenile or adult criminal justice system (Winn & Behizadeh, 2011). The pipeline has been an issue for over 20 years, plaguing the education and criminal justice systems in the United States. -

The Political Sociology of Juvenile Punishment: Treating Juvenile Offenders As Adults

THE POLITICAL SOCIOLOGY OF JUVENILE PUNISHMENT: TREATING JUVENILE OFFENDERS AS ADULTS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jason T. Carmichael, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2006 Dissertation Committee Approved by Professor David Jacobs, Adviser Professor J. Craig Jenkins Professor Zhenchao Qian __________________________________ Adviser Graduate Program in Sociology ABSTRACT Numerous studies have investigated the determinants of formal social control employed by the state to control its citizens. Only a small number have used explanations derive from conflict theory and political sociology. I follow this research tradition by hypothesizing that the threat produced by racial and ethnic minorities leads to increases in the demand for formal control mechanisms including more punitive responses to juvenile crime through adult sanctioning. I also consider broader political arguments that link the variation in punitive outcomes to differences in political arraignments across jurisdictions. While the punishment of juvenile offenders has increasingly become an issue of major concern to the public, there are few studies that test the governments coercive response to this particular type of offending. This dissertation addresses this issue by examining the treatment of juvenile offenders in the adult criminal system. First, I use pooled time- series negative binomial regression to analyze raw counts of juveniles admitted to adult prisons. Second, I use multivariate regression to predict the length of sentence that violent juvenile offenders receive in adult criminal courts. Finally, I use zero-inflated negative binomial regression to analyze the probability that states used the death penalty against juvenile when this practice was still constitutional. -

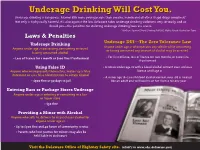

Underage Drinking Will Cost You

UnderageUnderage DrinkingDrinking WillWill CostCost You.You. Underage drinking is dangerous. Alcohol kills more young people than cocaine, heroin and all other illegal drugs combined.* Not only is it physically harmful, it’s also against the law. Delaware takes underage drinking violations very seriously, and so should you—the penalties for violating underage drinking laws are severe. * Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD): Myths About Alcohol for Teens Laws & Penalties Underage DUI—The Zero Tolerance Law Underage Drinking Underage DUI—The Zero Tolerance Law Anyone under age 21 who operates any vehicle while consuming Anyone under age 21 possessing, consuming or found or having consumed any amount of alcohol may be arrested. having consumed alcohol • Loss of license for 1 month or $100 fine if unlicensed • For first offense, loss of license for two months, or $200 fine if unlicensed Using False ID • A minor under age 18 with a blood alcohol content over .08 loses Anyone who misrepresents themselves, makes up a false license until age 21 statement or uses false identification to obtain alcohol • A minor age 18–21 with blood alcohol content over .08 is treated • $500 fine or 30 days in jail like an adult and will lose his or her license for one year Entering Bars or Package Stores Underage Anyone under age 21 entering or remaining in a bar or liquor store • $50 fine Providing a Minor with Alcohol Anyone who sells to, delivers to or purchases alcohol for anyone under age 21 • Up to $500 fine and 40 hours of community service • Parents who host parties for minors may also be held liable in civil court Visit the Delaware Office of Highway Safety site. -

Democracy Studies

Democracy Studies Democracy Studies Program website The goal of the Democracy Studies area (DMST) is to help students explore and critically examine the foundations, structures and purposes of diverse democratic institutions and practices in human experience. Democracy Studies combines a unique appreciation of Maryland’s democratic roots at St. Mary’s City with contemporary social and political scholarship, to better understand the value of democratic practices to human functioning and the contribution of democratic practices to a society’s development. The primary goal of the program of study is to provide students with a deeper understanding of how democracies are established, instituted and improved. Any student with an interest in pursuing the cross-disciplinary minor in Democracy Studies should consult with the study area coordinator or participating faculty member. Students are encouraged to declare their participation and intent to minor in the area as soon as possible, and no later than the end of the first week of the senior year. To successfully complete the cross-disciplinary minor in Democracy Studies, a student must satisfy the following requirements, designed to provide the depth and breadth of knowledge consistent with the goals of the field: Degree Requirements for the Minor General College Requirements General College requirements All requirements in a major field of study Required Courses At least 22 credit hours in courses approved for Democracy Studies, with a grade of C- or higher, including: HIST 200 (U.S. History, 1776-1980) or HIST 276 (20th Century World) or POSC 262 (Introduction to Democratic Political Thought) Additional courses from three different disciplines cross-listed with Democracy Studies to total 12 credit hours.