The Determinants of Women's Work: a Case Study from Three Urban Low-Income Communities in Amman, Jordan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The United Nations and Its Agencies: Unequal Financial Allocations, Mistreatment of Israel, and Straying from Its Mandates

The United Nations and its Agencies: Unequal Financial Allocations, Mistreatment of Israel, and Straying from its Mandates Ran Bar-Yoshafat Tevet 5779 – January 2019 Policy Paper no. 44 Attorney Ran Bar-Yoshafat Deputy Director of the Kohelet Policy Forum Ran is active in the fields of constitutional and international law, and public diplomacy. Ran received a Law degree from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, a Masters in Business from Tel-Aviv University, and a Masters in American Jewish History from Haifa University. The United Nations and its Agencies: Unequal Financial Allocations, Mistreatment of Israel, and Straying from its Mandates Ran Bar-Yoshafat Tevet 5779 – January 2019 Policy Paper no. 44 The United Nations and Its Agencies: Unequal Financial Allocations, Mistreatment of Israel, and Straying from its Mandates Attorney Ran Bar-Yoshafat Printed in Israel, January 2019 ISBN 978-965-7674-55-0 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................3 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 5 United Nations General Assembly (GA) .................................................................. 7 United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) ............................................ 11 Security Council Peacekeeping Operations and Political Missions .........13 Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process (UNSCO) ............17 Economic -

The Values, Beliefs, and Attitudes of Elites in Jordan Towards Political, Social, and Economic Development

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 6-3-2014 The Values, Beliefs, and Attitudes of Elites in Jordan towards Political, Social, and Economic Development Laila Huneidi Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Public Affairs Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Huneidi, Laila, "The Values, Beliefs, and Attitudes of Elites in Jordan towards Political, Social, and Economic Development" (2014). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 2017. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.2016 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Values, Beliefs, and Attitudes of Elites in Jordan towards Political, Social, and Economic Development by Laila Huneidi A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public Affairs and Policy Dissertation Committee: Masami Nishishiba, Chair Bruce Gilley Birol Yesilada Grant Farr Portland State University 2014 i Abstract This mixed-method study is focused on the values, beliefs, and attitudes of Jordanian elites towards liberalization, democratization and development. The study aims to describe elites’ political culture and centers of influence, as well as Jordan’s viability of achieving higher developmental levels. Survey results are presented. The study argues that the Jordanian regime remains congruent with elites’ political culture and other patterns of authority within the elite strata. -

Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia

Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia The Committee at the National Model United Nations Conference The United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) operates under the supervision of the United Nations Economic and Social Council, along with four other United Nations Regional Commissions.1 De facto, ESCWA is a framework for cooperation which aims to promote economic and social development in the region. As of 2012, the Commission is comprised of 17 predominantly Arab member states.2 It currently has 7 subsidiary bodies, which, but for the Committee on Transport who meets each year, meet biannually.3 The other six are the Statistical Committee; the Committee on Social Development; the Committee on Energy; the Committee on Water Resources; the Technical Committee on Liberalization of Foreign Trade, Economic Globalization and Financing for Development; and the Committee on Women.4 Format: The ESCWA is a Resolution Writing Committee. Voting: Each Member State in the ESCWA has one vote.5 The Voting Rights do not allow any Member State within the Commission veto power. Substantive decisions are made based on a majority vote of Member States who are present and voting.6 Recent Developments Since September 2012, the Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia has started a new phase in its attempt to promote the Digital Arabic Content (DAC) Industry through Technology Incubators.7 In 2003 ESCWA organized the first Expert Group Meeting (EGM) on Promotion of DAC with the objective of helping develop a DAC -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Acclaimed Leaders, Including Former Canadian Prime Minister and Nobel Laureate, to Jury Inaugural Global Pluralism Award

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Acclaimed leaders, including former Canadian Prime Minister and Nobel Laureate, to jury inaugural Global Pluralism Award Ottawa, Canada – August 17, 2016 – A jury of international leaders, chaired by the Rt. Hon. Joe Clark, former Canadian Prime Minister, has been named to select the winners of the first inaugural Global Pluralism Award. The Award recognizes individuals and organisations whose high-impact, innovative initiatives are tackling the challenge of living peacefully and productively with diversity. The Award is a program of the Global Centre for Pluralism, an international research and education centre founded by His Highness the Aga Khan in partnership with the Government of Canada. The members of the jury represent a range of sectors, including local government, the business world and civil society. Through their own work on inclusive citizenship, social welfare and community development, the jury members all appreciate first-hand the extraordinary effort it takes to build societies where differences are valued and respected. Their expertise will inform the selection process for the top three awardees, who will be named at a ceremony in Ottawa, Canada in November 2017 at the Global Centre for Pluralism’s new international headquarters. The jury includes: o The Right Honourable Joe Clark, former Prime Minister and Foreign Affairs Minister of Canada, Canada (Chair) o Rima Khalaf, Executive Secretary, United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, Jordan o Naheed Nenshi, Mayor of Calgary, Canada o Bience Gawanas, Lawyer & Special Advisor to the Minister of Poverty Eradication and Social Welfare, Namibia o Rigoberta Menchú, Indigenous rights activist & Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, Guatemala o Pascale Thumerelle, Vice-president, Head of Corporate Social Responsibility, Vivendi, France Bio notes for jury members are attached. -

The Israel Apartheid Analogy

The Israel Apartheid Analogy Contests over Meaning in a War over Words Student: Isabel de Kanter Student Number: 5697271 University: Utrecht University Faculty: Humanities Department: Philosophy and Religious Studies Bachelor: Islam and Arabic Thesis Advisor: Dr. Eric Ottenheijm Second Reader: Dr. Joas Wagemakers PLAGIARISM DECLARATION I confirm that I have read and understood the plagiarism guidelines as described in the Education and Examination Regulations of Utrecht University. I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work, that it has not been copied from any published or unpublished work and that it has not previously been submitted for assessment either at Utrecht University or elsewhere. Each contribution and quotation in this thesis from the work of other people has been appropriately cited and referenced, using the Chicago Manual of Style 17th Edition. ABSTRACT In the wake of the Six Day War in 1967, Israel became an occupying power with the conquest of the Golan Heights, Sinai Peninsula, Gaza Strip and West Bank, including East Jerusalem. Since the 1970s, comparisons have increasingly been drawn by authorities in the UN, human rights organisations, political commentators and protest movements, between the South African system of apartheid and Israeli policies in the occupied territories. This thesis explores the historical development of the Israel apartheid analogy and its use in public discourse. Not only by analysing secondary literature, but also by conducting a case study, in which articles are examined from high circulation Israeli and Palestinian centrist newspapers the Jerusalem Post and Al-Quds, in the period between January 1st 2017 and May 15th 2018. -

9. Palestine‒Israel Doaa’ Elnakhala

9. Palestine‒Israel Doaa’ Elnakhala BACKGROUND Palestine is an area of about 26 000 km², located to the southeast of the Mediterranean, and is comprised of modern-day Israel, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. This area contains sacred sites for Jews, Christians and Muslims. Since the late 19th century, it has been subjected to conflicting claims by Jewish and Arab national movements. Jewish claims are based on the biblical promise to Abraham and his descendants that Palestine was the site of the Jewish kingdom of Israel, destroyed by the Romans. Palestinian claims are based on continuous residence for hundreds of years, and on constituting the majority of the population at various times in the conflict, including the end of the British Mandate and the creation of the State of Israel, in 1948. Some also add that, since Abraham’s son Ishmael is the forefather of the Arabs, then God’s promise to the children of Abraham also includes the Arabs (Beinin and Hajjar, 2014, p. 1). Waves of Jewish immigration arrived in Palestine during the Ottoman Rule and the British Mandate.1 In 1917, the British promised a Jewish homeland in Palestine through the Balfour Declaration (Balfour, 1917), which contradicted their promise to the Arabs of Palestine, of their own independent state on the same land (Antonius, 2010).2 Concerned over a demographic threat and a gradual loss of land to the Jewish migrants, the Palestinian Arabs rioted against the British Authorities, accusing them of conspiring with the Jews. With support from different sources, the influence of the Jewish population expanded as tensions continued to escalate (Pappé, 2006; Elnakhala, 2014). -

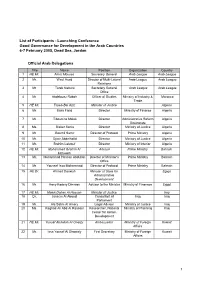

Final List of Participants 6-7 Feb 05

List of Participants - Launching Conference Good Governance for Development in the Arab Countries 6-7 February 2005, Dead Sea, Jordan Official Arab Delegations Title Name Position Organization Country 1 HE Mr. Amro Moussa Secretary General Arab League Arab League 2 Mr. Wael Asad Director of Multi-Lateral Arab League Arab League Relations 3 Mr. Tarek Nabulsi Secretary General Arab League Arab League Office 4 Mr. Abdelazez Rabah Officer of Studies Ministry of Industry & Morocco Trade 5 HE Mr. Tayeb Bel Aziz Minister of Justice Algeria 6 Mr. Baka Farid Director Ministry of Finance Algeria 7 Mr. Tiboutrine Malek Director Administrative Reform Algeria Directorate 8 Ms. Bisker Sonia Director Ministry of Justice Algeria 9 Mr. Bourhil Samir Director of Protocol Prime Ministry Algeria 10 Mr. Djarir Abdelhafid Director Ministry of Justice Algeria 11 Mr. Brahim Lakrouf Director Ministry of Interior Algeria 12 HE Mr. Mohammad Ibrahim Al Advisor Prime Ministry Bahrain Motaweh 13 Mr. Mohammad Hassan Abdullah Director of Minister's Prime Ministry Bahrain Office 14 Mr. Youssef Issa Mohammad Director of Protocol Prime Ministry Bahrain 15 HE Dr. Ahmad Darwish Minister of State for Egypt Administrative Development 16 Mr. Hany Kadery Dimnian Advisor to the Minister Ministry of Finanace Egypt 17 HE Mr. Malek Dahan Al Hassan Minister of Justice Iraq 18 Dr. Jassem Al Aboudi Consultant of Iraq Iraq Parliament 19 Mr. Ala Salim Al Amery Legal Advisor Ministry of Justice Iraq 20 Ms. Raghad Ali Abd Al Rassoul Researcher, National Ministry of Planning Iraq Center for Admin. Development 21 HE Mr. Yousef Abdullah Al Onaizy Ambassador Ministry of Foreign Kuwait Affairs 22 Mr. -

The Information Revolution in the Middle East and North Africa

National Defense Research Institute THE INFORMATION REVOLUTION IN THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA Grey E. Burkhart Susan Older R Prepared for the National Intelligence Council Approved for public release; distribution unlimited The research described in this report was sponsored by the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD). The research was conducted in RAND’s National Defense Research Institute, a federally funded research and development center supported by the OSD, the Joint Staff, the unified commands, and the defense agencies under Contract DASW01-01-C-0004. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Burkhart, Grey E. The information revolution in the Middle East and North Africa : MR-1653 / Grey E. Burkhart, Susan Older. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-8330-3323-9 (pbk.) 1. Information technology—Economic aspects—Middle East. 2. Information technology—Economic aspects—Africa, North. 3. Information technology—Social aspects—Middle East. 4. Information technology—Social aspects—Africa, North. 5. Information technology—Government policy—Middle East. 6. Information technology—Government policy—Africa, North. 7. Globalization. I. Older, Susan. II.Title. HC415.15.Z9I552 2003 303.48'33'0956—dc21 2002154572 RAND is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND® is a registered trademark. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of its research sponsors. © Copyright 2003 RAND All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from RAND. Published 2003 by RAND 1700 Main Street, P.O. -

Conference of the States Parties

OPCW Conference of the States Parties Fourteenth Session C-14/DEC.2 30 November – 4 December 2009 30 November 2009 Original: ENGLISH DECISION ATTENDANCE BY NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANISATIONS AT THE FOURTEENTH SESSION OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE STATES PARTIES The Conference of the States Parties, Bearing in mind Rule 33 of its Rules of Procedure, Hereby: Approves the participation of the non-governmental organisations (NGOs) whose names appear in the list annexed hereto in the Fourteenth Session of the Conference of the States Parties (hereinafter “the Conference”), and decides on the following arrangements with respect to the representatives of these NGOs: (a) They will be invited, subject to the decision of the Conference, to attend open meetings of its plenary sessions; (b) They will be issued with name tags, which must be worn within the World Forum Convention Centre (WFCC); (c) They may place literature for distribution at designated sites; and (d) They will be provided, on request, with all documents referred to in the annotated agenda for the Fourteenth Session of the Conference and distributed during that session, except for conference room papers and other draft documents. Annex (English only): List of Non-Governmental Organisations Entitled to Participate in the Fourteenth Session of the Conference of the States Parties CS-2009-6207(E) distributed 04/12/2009 *CS-2009-6207.E* C-14/DEC.2 Annex page 2 Annex LIST OF NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANISATIONS ENTITLED TO PARTICIPATE IN THE FOURTEENTH SESSION OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE STATES PARTIES 1. Arms Control Association (ACA) 2. American University in Cairo (AUC) 3. -

Secretariats and Executive Secretaries of the UN Regional Commissions: an Exploration

Secretariats and Executive Secretaries of the UN Regional Commissions: An Exploration Paper for the ACUNS Annual Meeting in New York, 16-18 June 2016 Panel: Executive Heads, Secretariats, NGOs, and Civil Society: Evolution and Change in the UN System Bob Reinalda Radboud University Nijmegen, Netherlands, [email protected] IO BIO Editor, www.ru.nl/fm/iobio Please do not quote this uncorrected draft Meeting the challenges of development and dignity is the topic of this ACUNS Annual Meeting. This paper focuses on the so-called Regional Commissions of the United Nations (UN), which – generally speaking – have not received much attention. They are not particularly recognizable as institutions, but do function as bridges between the universal organization (the UN) and its major ‘regions’ (mostly continents), given the objectives of discussing economic and social issues in specific regions and of strengthening regional cooperation as well as cooperation with the rest of the world. These Regional Commissions are ECA for Africa, ECE for Europe, ECLAC for Central and Latin America, ESCAP for Asia and the Pacific and ESCWA for Western Asia. They have a small joint Office in New York. The paper furthermore focuses on a specific organ of these Regional Commissions, namely their Secretariats. We know relatively little about the Secretariats of international organizations (IOs), mainly due to the fact that the general focus of research is on the entire organization and its actions, rather than on this and other specific organs. The Secretariat however is an entity that follows the mandate of the organization and the decisions of the assembly of member states, but it also is the place where IO actorness originates. -

Women's Political Representation in the Arab Region

Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia Women’s Political Representation in the Arab Region E/ESCWA/ECW/2017/3 Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) Women’s Political Representation in the Arab Region United Nations Beirut, 2017 © 2017 United Nations All rights reserved worldwide Photocopies and reproductions of excerpts are allowed with proper credits. All queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA), e-mail: [email protected]. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations or its officials or Member States. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the status of any country, territory, city or area, its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Links contained in this publication are provided for the convenience of the reader and are correct at the time of issue. The United Nations takes no responsibility for the continued accuracy of that information or for the content of any external website. References have, wherever possible, been verified. Mention of company names and commercial products does not imply the endorsement of the United Nations Secretariat. References to dollars ($) are to United States dollars, unless otherwise stated. Symbols of the United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. -

Curriculum Vitae Address Education Current and Past Positions

January 2013 Curriculum Vitae Djavad Salehi-Isfahani Address Department of Economics (0316) Office: (540) 231-7697 Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Fax: (540) 231-5097 3016 Pamplin Hall e-mail: [email protected] Blacksburg, VA 24061 Education 1971 B.Sc. in Economics, University of London (Queen Mary College) 1974 M.A. in Economics, Harvard University 1977 Ph.D. in Economics, Harvard University Current and past positions 2001-present Professor, Department of Economics, Virginia Tech 2009-present Non-resident Senior Fellow, Global Economy and Development, the Brookings Institution 2010-2011 Research Associate, Dubai Initiative, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University 2009-2010 Research Fellow, Dubai Initiative, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University 2008-2009 Nonresident Guest Scholar, Wolfensohn Center for Development, the Brookings Institution 2007-2008 Visiting Fellow, Wolfensohn Center for Development, the Brookings Institution 2001 (spring) Visiting Professor, Institute for Research in Planning and Development, Tehran, Iran. 1996-2000 Head, Department of Economics, Virginia Tech 1995-96 Interim Department Head, Department of Economics, Virginia Tech 1991-92 Visiting Professor, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, and Senior Associate Member, St. Anthony's College, the University of Oxford 1990-2001 Associate Professor of Economics, Virginia Tech 1984-90 Assistant Professor of Economics, Virginia Tech 1977-84 Assistant Professor of Economics, University of Pennsylvania 1979-80 Economist, Department of Economic Research, the Central Bank of Iran 1981-84 Research Associate, Middle East Research Institute, University of Pennsylvania 1977-84 Research Associate, Center for Population Studies, University of Pennsylvania 2 Other Professional Appointments 2011- Associate Editor, Middle East Development Journal.