Grice's Theory of Conversational Implicatures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies

Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies Working with Autism Spectrum Disorders & Related Communication & Social Skill Challenges Linda Hodgdon, M.Ed., CCC-SLP Speech-Language Pathologist Consultant for Autism Spectrum Disorders [email protected] Learning effective conversation skills ranks as one of the most significant social abilities that students with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) need to accomplish. Educators and parents list the challenges: “Steve talks too much.” “Shannon doesn’t take her turn.” “Aiden talks when no one is listening.” “Brandon perseverates on inappropriate topics.” “Kim doesn’t respond when people try to communicate with her.” The list goes on and on. Difficulty with conversation prevents these students from successfully taking part in social opportunities. What makes learning conversation skills so difficult? Conversation requires exactly the skills these students have difficulty with, such as: • Attending • Quickly taking in and processing information • Interpreting confusing social cues • Understanding vocabulary • Comprehending abstract language Many of those skills that create skillful conversation are just the ones that are difficult as a result of the core deficits in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Think about it. From the student’s point of view, conversation can be very puzzling. Conversation is dynamic. .fleeting. .changing. .unpredictable. © Linda Hodgdon, 2007 1 All Rights Reserved This article may not be duplicated, -

Cooperative Principle in Oral English Teaching

Vol. 2, No. 3 International Education Studies Cooperative Principle in Oral English Teaching Mai Zhou School of Foreign Languages, Zhejiang Gongshang University 18 Xue Zheng Street, Hangzhou 310018, China E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The Cooperative Principle by American linguist Grice is one of the major principles guiding people’s communication. Observing the Cooperative Principle will be helpful for people to improve the flexibility and accuracy of language communication. The ultimate aim of spoken English teaching is to develop students’ communicative competence. Therefore, it is significant to apply the Cooperative Principle to oral English teaching. This paper tries to prove the applicability of Cooperative Principle in spoken English teaching. Keywords: Cooperative Principle, Oral English teaching, Communicative competence, Pragmatics 1. Introduction Grice’s concept of the Cooperative Principle and its four associated maxims are considered a major contribution to the area of pragmatics, which not only plays an indispensable role in the generation of conversational implications, but also is a successful example showing how human communication is governed by the principle. In foreign language teaching, the four basic skills have been greatly improved for Chinese college students in the past decades. However, these skills have not been developed at the same pace, especially the ability in speaking. Some college students can understand what others say in English but cannot express themselves effectively in English, and some even cannot catch others’ meaning conveyed by spoken English. Speaking still remains the most difficult skill for the majority of college students, who remain poor in oral communication in English after years of study in universities. -

Application of Cooperative Principle and Politeness Principle in Class Question-Answer Process

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 7, No. 7, pp. 563-569, July 2017 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0707.10 Application of Cooperative Principle and Politeness Principle in Class Question-answer Process Lulu Liu Shanxi Normal University, Linfen, China Abstract—Question-answer method of teaching is one of the common ways of classroom interaction and it is also a bridge of communication and cooperation between teachers and students. Teachers can check and know students’ understanding of the knowledge and guide students to think of problems activity by asking questions. The paper is justified by correlational theories of Cooperative Principle and Politeness Principle. Research method of literature is conducted. That is, teachers should pay attention to the way and method of asking questions in class question-answer process, who express to euphemism and accurate as soon as possible and give affirmation and encouragement for students answer to improve the amount of language output. The teachers should be skillful in using of the major principles of Cooperative Principle and Politeness Principle in the English Classroom quiz. These theories not only help to establish a harmonious teacher-students relationship, but also improve the effect of classroom teaching. Index Terms—class question-answer, Cooperative Principle, English, Politeness Principle I. INTRODUCTION Cooperative Principle and Politeness Principle are the most important theories in the field of pragmatics. Both of the two principles have attracted the researcher’s attention. Grace put forward the theory of “Cooperative Principle” in the late 1960s who was a famous American philosopher Linguists. Leech proposed the theory of “Politeness Principle in 1983”. -

A Study of Principle of Conversation in Advertising Language

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 2, No. 12, pp. 2619-2623, December 2012 © 2012 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.2.12.2619-2623 A Study of Principle of Conversation in Advertising Language Fang Liu Changchun University of Science and Technology, Changchun, China Email: [email protected] Abstract—Principle of Conversation includes Grice’s Cooperative Principle (CP) and Leech’s Politeness Principle (PP). Advertising language can produce conversational implicatures and exert stronger persuasive effect by observing and violating the Cooperative Principle. At the same time, some public service advertisements comply with the Politeness Principle. The paper offers a wider way for advertising designers to create excellent advertisements and also make them pay attention to some problems existing in ads. On the other hand, it is also of great help for consumers to understand the implied meaning of advertisements and avoid being tempted into buying some poor quality products by some deceptive advertising. Index Terms—the Cooperative Principle, the Politeness Principle, advertising language, conversational implicature, influencing factors I. INTRODUCTION In modern society, advertising has invaded every aspect of our life. It has exerted great impact on modern people’s lifestyles. We are surrounded by various kinds of advertisements. Whenever we open a newspaper or a magazine, turn on the TV or the radio, or look at the billboards in subways or on buildings, we are exposed to various advertisements. Since advertisements have penetrated our lives deeply, studies on it have been carried on before and more attention on it also appears necessary. As a special form of communication, most commercial advertisements are actually a kind of persuasive speech act with an aim to persuade consumers into buying or accepting certain product or service. -

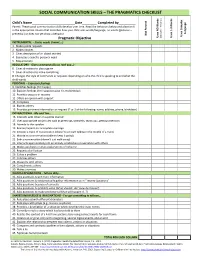

Social Communication Skills – the Pragmatics Checklist

SOCIAL COMMUNICATION SKILLS – THE PRAGMATICS CHECKLIST Child’s Name Date .Completed by . Words Preverbal) Parent: These social communication skills develop over time. Read the behaviors below and place an X - 3 in the appropriate column that describes how your child uses words/language, no words (gestures – - Language preverbal) or does not yet show a behavior. Present Not Uses Complex Uses Complex Gestures Uses Words NO Uses 1 Pragmatic Objective ( INSTRUMENTAL – States needs (I want….) 1. Makes polite requests 2. Makes choices 3. Gives description of an object wanted 4. Expresses a specific personal need 5. Requests help REGULATORY - Gives commands (Do as I tell you…) 6. Gives directions to play a game 7. Gives directions to make something 8. Changes the style of commands or requests depending on who the child is speaking to and what the child wants PERSONAL – Expresses feelings 9. Identifies feelings (I’m happy.) 10. Explains feelings (I’m happy because it’s my birthday) 11. Provides excuses or reasons 12. Offers an opinion with support 13. Complains 14. Blames others 15. Provides pertinent information on request (2 or 3 of the following: name, address, phone, birthdate) INTERACTIONAL - Me and You… 16. Interacts with others in a polite manner 17. Uses appropriate social rules such as greetings, farewells, thank you, getting attention 18. Attends to the speaker 19. Revises/repairs an incomplete message 20. Initiates a topic of conversation (doesn’t just start talking in the middle of a topic) 21. Maintains a conversation (able to keep it going) 22. Ends a conversation (doesn’t just walk away) 23. -

Grice's Theory of Implicature and the Meaning of the Sentential

Gergely Bottyán The operationality of Grice’s tests for implicature 1. Introduction In less than a decade after its first publication in 1975, Herbert Paul Grice’s paper Logic and conversation becomes one of the classic treatises of the linguistic subdiscipline now standardly referred to as pragmatics. There are at least two reasons for the paper’s success: (i) it can be regarded as the first truly serious attempt to clarify the intuitive difference between what is expressed literally in a sentence and what is merely suggested by an utterance of the same string of words, (ii) the components of the notional and inferential framework that Grice set up to characterize various kinds of utterance content are intuitively appealing (cf. Haberland & Mey 2002). The present paper has two related aims: (i) to give a comprehensive overview of Grice’s theory of implicature, and (ii) to investigate whether it is possible to test the presence of a conversational implicature on the basis of some or all of the properties that Grice attributes to this construct. It will be argued that of the six characteristics listed by Grice, only cancellability is a practical criterion. However, cancellability is not a sufficient condition of the presence of a conversational implicature. Therefore, additional criteria are needed to arrive at an adequate test. 2. Overview of Grice’s theory of implicature Most of the body of Grice 1975=1989a consists in an attempt to clarify the intuitive difference between what is expressed literally in a sentence and what is merely suggested or hinted at by an utterance of the same string of words. -

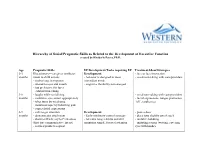

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills As Related to the Development of Executive Function Created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills as Related to the Development of Executive Function created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D. Age Pragmatic Skills EF Development/Tasks requiring EF Treatment Ideas/Strategies 0-3 Illocutionary—caregiver attributes Development: - face to face interaction months intent to child actions - behavior is designed to meet - vocal-turn-taking with care-providers - smiles/coos in response immediate needs - attends to eyes and mouth - cognitive flexibility not emerged - has preference for faces - exhibits turn-taking 3-6 - laughs while socializing - vocal turn-taking with care-providers months - maintains eye contact appropriately - facial expressions: tongue protrusion, - takes turns by vocalizing “oh”, raspberries. - maintains topic by following gaze - copies facial expressions 6-9 - calls to get attention Development: - peek-a-boo months - demonstrates attachment - Early inhibitory control emerges - place toys slightly out of reach - shows self/acts coy to Peek-a-boo - tolerates longer delays and still - imitative babbling (first true communicative intent) maintains simple, focused attention - imitating actions (waving, covering - reaches/points to request eyes with hands). 9-12 - begins directing others Development: - singing/finger plays/nursery rhymes months - participates in verbal routines - Early inhibitory control emerges - routines (so big! where is baby?), - repeats actions that are laughed at - tolerates longer delays and still peek-a-boo, patta-cake, this little piggy - tries to restart play maintain simple, -

A Communication Aid Which Models Conversational Patterns

A communication aid which models conversational patterns. Norman Alm, Alan F. Newell & John L. Arnott. Published in: Proc. of the Tenth Annual Conference on Rehabilitation Technology (RESNA ‘87), San Jose, California, USA, 19-23 June 1987, pp. 127-129. A communication aid which models conversational patterns Norman ALM*, Alan F. NEWELL and John L. ARNOTT University of Dundee, Dundee DD1 4HN, Scotland, U.K. The research reported here was published in: Proceedings of the Tenth Annual Conference on Rehabilitation Technology (RESNA ’87), San Jose, California, USA, 19-23 June 1987, pp. 127-129. The RESNA (Rehabilitation Engineering and Assistive Technology Society of North America) site is at: http://www.resna.org/ Abstract: We have developed a prototype communication system that helps non-speakers to perform communication acts competently, rather than concentrating on improving the production efficiency for specific letters, words or phrases. The system, called CHAT, is based on patterns which are found in normal unconstrained dialogue. It contains information about the present conversational move, the next likely move, the person being addressed, and the mood of the interaction. The system can move automatically through a dialogue, or can offer the user a selection of conversational moves on the basis of single keystrokes. The increased communication speed which is thus offered can significantly improve both the flow of the conversation and the disabled person’s control of the dialogue. * Corresponding author: Dr. N. Alm, University of Dundee, Dundee DD1 4HN, Scotland, UK. A communication aid which models conversational patterns INTRODUCTION The slow rate of communication of people using communication aids is a crucial problem. -

Conversational Implicatures (And How to Spot Them)

Conversational Implicatures (and How to Spot Them) Michael Blome-Tillmann McGill University Abstract In everyday conversations we often convey information that goes above and beyond what we strictly speaking say: exaggeration and irony are obvious examples. H.P. Grice intro- duced the technical notion of a conversational implicature in systematizing the phenom- enon of meaning one thing by saying something else. In introducing the notion, Grice drew a line between what is said, which he understood as being closely related to the conventional meaning of the words uttered, and what is conversationally implicated, which can be inferred from the fact that an utterance has been made in context. Since Grice’s seminal work, conversational implicatures have become one of the major re- search areas in pragmatics. This article introduces the notion of a conversational implica- ture, discusses some of the key issues that lie at the heart of the recent debate, and expli- cates tests that allow us to reliably distinguish between semantic entailments and conven- tional implicatures on the one hand and conversational implicatures on the other.1 Conversational Implicatures and their Cancellability In everyday conversations our utterances often convey information that goes above and beyond the contents that we explicitly assert or—as Grice puts it—beyond what is said by our utterances. Consider the following examples:2 (1) A: Can I get petrol somewhere around here? B: There’s a garage around the corner. [A can get petrol at the garage around the corner.] (2) A: Is Karl a good philosopher? B: He’s got a beautiful handwriting. -

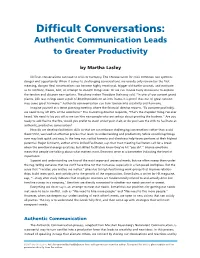

Difficult Conversations: Authentic Communication Leads to Greater Productivity

Difficult Conversations: Authentic Communication Leads to Greater Productivity by Martha Lasley Difficult conversations can lead to crisis or harmony. The Chinese word for crisis combines two symbols: danger and opportunity. When it comes to challenging conversations, we usually only remember the first meaning, danger. Real conversations can become highly emotional, trigger old battle wounds, and motivate us to confront, freeze, bolt, or attempt to smooth things over. Or we can choose lively discussions to explore the tension and discover new options. The piano maker Theodore Steinway said, “In one of our concert grand pianos, 243 taut strings exert a pull of 40,000 pounds on an iron frame. It is proof that out of great tension may come great harmony.” Authentic communication can turn tension into creativity and harmony. Imagine yourself at a tense planning meeting where the financial director reports, “To compete profitably, we need to lay off 20% of the workforce.” The marketing director responds, “That’s the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard. We need to lay you off so we can hire new people who are serious about growing the business.” Are you ready to add fuel to the fire, would you prefer to crawl under your chair, or do you have the skills to facilitate an authentic, productive conversation? How do we develop facilitation skills so that we can embrace challenging conversations rather than avoid them? First, we need an effective process that leads to understanding and productivity. While smoothing things over may look quick and easy, in the long run, radical honesty and directness help teams perform at their highest potential. -

How We Talk About How We Talk: Communication Theory in the Public Interest by Robert T

20042004 ICA ICAPresidential Presidential Address Address How We Talk About How We Talk: Communication Theory in the Public Interest by Robert T. Craig This article is a revision of the author’s presidential address to the 54th annual conference of the International Communication Association, presented May 29, 2004, in New Orleans, Louisiana. Using recent public discourse on talk and drugs as an example, it reflects on our culture’s preoccupation with communication and the pervasiveness of metadiscourse (talk about talk for practical purposes) in pri- vate, public, and academic discourses. It argues that communication theory can be used to describe and analyze the common vocabularies of public metadiscourse, critique assumptions about communication embedded in those vocabularies, and contribute useful new ways of talking about talk in the public interest. “Talk to your kids.” “Talk to your kids about drugs.” “Talk to your doctor.” “Talk to your doctor about Ambien.” “Ask you doctor if Lipitor is right for you.” “Ask your doctor if Advair is right for you.” “Talk. Know. Ask.” “Questions: The antidrug.” This collage of quotations selected from recent drug company commercials and antidrug public service announcements highlights a well-known irony in the pub- lic discourse on drugs that is not, however, my main point. Yes, the culture that produced these ads is rather obsessed with drugs. That culture is also rather obsessed with talk or, more generally, with communication. Both obsessions are on display in these ads in interesting juxtaposition. Drugs, in this cultural logic, are powerful and therefore as dangerous as they are desirable. They solve problems and they cause problems. -

The Phrasal Implicature Theory of Metaphors and Slurs

THE PHRASAL IMPLICATURE THEORY OF METAPHORS AND SLURS Alper Yavuz A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2018 Full metadata for this thesis is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this thesis: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/13189 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence The Phrasal Implicature Theory of Metaphors and Slurs Alper Yavuz This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) at the University of St Andrews March 2018 Abstract This thesis develops a pragmatic theory of metaphors and slurs. In the pragmatic literature, theorists mostly hold the view that the framework developed by Grice is only applicable to the sentence-level pragmatic phenomena, whereas the subsenten- tial pragmatic phenomena require a different approach. In this thesis, I argue against this view and claim that the Gricean framework, after some plausible revisions, can explain subsentential pragmatic phenomena, such as metaphors and slurs. In the first chapter, I introduce three basic theses I will defend and give an outline of the argument I will develop. The second chapter discusses three claims on metaphor that are widely discussed in the literature. There I state my aim to present a theory of metaphor which can accommodate these three claims. Chapter3 introduces the notion of \phrasal implicature", which will be used to explain phrase- level pragmatic phenomena with a Gricean approach. In Chapter4, I present my theory of metaphor, which I call \phrasal implicature theory of metaphor" and discuss certain aspects of the theory.