Cutaneous Branch of the Obturator Nerve Extending to the Medial Ankle and Foot: a Report of Two Cadaveric Cases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study of Anatomical Pattern of Lumbar Plexus in Human (Cadaveric Study)

54 Az. J. Pharm Sci. Vol. 54, September, 2016. STUDY OF ANATOMICAL PATTERN OF LUMBAR PLEXUS IN HUMAN (CADAVERIC STUDY) BY Prof. Gamal S Desouki, prof. Maged S Alansary,dr Ahmed K Elbana and Mohammad H Mandor FROM Professor Anatomy and Embryology Faculty of Medicine - Al-Azhar University professor of anesthesia Faculty of Medicine - Al-Azhar University Anatomy and Embryology Faculty of Medicine - Al-Azhar University Department of Anatomy and Embryology Faculty of Medicine of Al-Azhar University, Cairo Abstract The lumbar plexus is situated within the substance of the posterior part of psoas major muscle. It is formed by the ventral rami of the frist three nerves and greater part of the fourth lumbar nerve with or without a contribution from the ventral ramus of last thoracic nerve. The pattern of formation of lumbar plexus is altered if the plexus is prefixed (if the third lumbar is the lowest nerve which enters the lumbar plexus) or postfixed (if there is contribution from the 5th lumbar nerve). The branches of the lumbar plexus may be injured during lumbar plexus block and certain surgical procedures, particularly in the lower abdominal region (appendectomy, inguinal hernia repair, iliac crest bone graft harvesting and gynecologic procedures through transverse incisions). Thus, a better knowledge of the regional anatomy and its variations is essential for preventing the lesions of the branches of the lumbar plexus. Key Words: Anatomical variations, Lumbar plexus. Introduction The lumbar plexus formed by the ventral rami of the upper three nerves and most of the fourth lumbar nerve with or without a contribution from the ventral ramous of last thoracic nerve. -

Neurotization of Femoral Nerve Using the Anterior Branch of the Obturator Nerve

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Eur. J. Anat. 21 (1): 129-133(2017) Neurotization of femoral nerve using the anterior branch of the obturator nerve Francisco Martínez-Martínez1, María Ll. Guerrero-Navarro2, Miguel Sáez- Soto1, José M. Moreno-Fernández1, Antonio García-López3 1Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia (Spain) 2Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía, Cartagena (Spain) 3Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Hospital General Universitario de Alicante (Spain) SUMMARY INTRODUCTION Nerve transfer is nowadays a standard proce- Femoral nerve injuries are an infrequent patholo- dure for motor reinnervation. There is a vast num- gy but quite invalidating. These might be second- ber of articles in the literature which describe dif- ary to trauma or abdominal surgery. ferent techniques of neurotization performed after The aim of the surgical treatment is to achieve brachial plexus injuries. Although lower limb nerve muscle reinnervation through a nerve transfer or transfers have also been studied, the number of nerve graft in order to regain adequate gait. articles are much limited. The sacrifice of a donor Nerve transfer or neurotization is a surgical tech- nerve to reinnervate a disrupted one causes mor- nique which consists on sectioning a nerve or a bidity of whichever structures that healthy nerve fascicle of it and then anastomose it to a distal innervated before the transfer. New studies are stump of an injured nerve. The donor nerve will focused on isolating branches or fascicles of the necessarily lose its function in order to provide in- main donor trunk that can also be useful for rein- nervation to the receptor nerve (Narakas, 1984). -

A Cadaveric Study of Ultrasound-Guided Subpectineal Injectate Spread Around the Obturator Nerve and Its Hip Articular Branches

REGIONAL ANESTHESIA AND ACUTE PAIN Regional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine: first published as 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000587 on 1 May 2017. Downloaded from ORIGINAL ARTICLE A Cadaveric Study of Ultrasound-Guided Subpectineal Injectate Spread Around the Obturator Nerve and Its Hip Articular Branches Thomas D. Nielsen, MD,* Bernhard Moriggl, MD, PhD, FIACA,† Kjeld Søballe, MD, DMSc,‡ Jens A. Kolsen-Petersen, MD, PhD,* Jens Børglum, MD, PhD,§ and Thomas Fichtner Bendtsen, MD, PhD* such high-volume blocks the most appropriate nerve blocks for Background and Objectives: The femoral and obturator nerves are preoperative analgesia in patients with hip fracture, because both assumed to account for the primary nociceptive innervation of the hip joint the femoral and obturator nerves have been found to innervate capsule. The fascia iliaca compartment block and the so-called 3-in-1-block the hip joint capsule.5 have been used in patients with hip fracture based on a presumption that local Several authors have since questioned the reliability of the anesthetic spreads to anesthetize both the femoral and the obturator nerves. FICB and the 3-in-1-block to anesthetize the obturator nerve.6–10 Evidence demonstrates that this presumption is unfounded, and knowledge Recently, a study, using magnetic resonance imaging to visualize about the analgesic effect of obturator nerve blockade in hip fracture patients the spread of the injectate, refuted any spread of local anesthetic to presurgically is thus nonexistent. The objectives of this cadaveric study were the obturator nerve after either of the 2 nerve block techniques.11 to investigate the proximal spread of the injectate resulting from the admin- Consequently, knowledge of the analgesic effect of an obturator istration of an ultrasound-guided obturator nerve block and to evaluate the nerve block in preoperative patients with hip fracture is nonexis- spread around the obturator nerve branches to the hip joint capsule. -

ANATOMICAL VARIATIONS and DISTRIBUTIONS of OBTURATOR NERVE on ETHIOPIAN CADAVERS Berhanu KA, Taye M, Abraha M, Girma A

https://dx.doi.org/10.4314/aja.v9i1.1 ORIGINAL COMMUNICATION Anatomy Journal of Africa. 2020. Vol 9 (1): 1671 - 1677. ANATOMICAL VARIATIONS AND DISTRIBUTIONS OF OBTURATOR NERVE ON ETHIOPIAN CADAVERS Berhanu KA, Taye M, Abraha M, Girma A Correspondence to Berhanu Kindu Ashagrie Email: [email protected]; Tele: +251966751721; PO Box: 272 Debre Tabor University , North Central Ethiopia ABSTRACT Variations in anatomy of the obturator nerve are important to surgeons and anesthesiologists performing surgical procedures in the pelvic cavity, medial thigh and groin regions. They are also helpful for radiologists who interpret computerized imaging and anesthesiologists who perform local anesthesia. This study aimed to describe the anatomical variations and distribution of obturator nerve. The cadavers were examined bilaterally for origin to its final distribution and the variations and normal features of obturator nerve. Sixty-seven limbs sides (34 right and 33 left sides) were studied for variation in origin and distribution of obturator nerve. From which 88.1% arises from L2, L3 and L4 and; 11.9% from L3 and L4 spinal nerves. In 23.9%, 44.8% and 31.3% of specimens the bifurcation levels of obturator nerve were determined to be intrapelvic, within the obturator canal and extrapelvic, respectively. The anterior branch subdivided into two, three and four subdivisions in 9%, 65.7% and 25.4% of the specimens, respectively, while the posterior branch provided two subdivisions in 65.7% and three subdivisions in 34.3% of the specimens. Hip articular branch arose from common obturator nerve in 67.2% to provide sensory innervation to the hip joint. -

The Nerves of the Adductor Canal and the Innervation of the Knee: An

REGIONAL ANESTHESIA AND ACUTE PAIN Regional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine: first published as 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000389 on 1 May 2016. Downloaded from ORIGINAL ARTICLE The Nerves of the Adductor Canal and the Innervation of the Knee An Anatomic Study David Burckett-St. Laurant, MBBS, FRCA,* Philip Peng, MBBS, FRCPC,†‡ Laura Girón Arango, MD,§ Ahtsham U. Niazi, MBBS, FCARCSI, FRCPC,†‡ Vincent W.S. Chan, MD, FRCPC, FRCA,†‡ Anne Agur, BScOT, MSc, PhD,|| and Anahi Perlas, MD, FRCPC†‡ pain in the first 48 hours after surgery.3 Femoral nerve block, how- Background and Objectives: Adductor canal block contributes to an- ever, may accentuate the quadriceps muscle weakness commonly algesia after total knee arthroplasty. However, controversy exists regarding seen in the postoperative period, as evidenced by its effects on the the target nerves and the ideal site of local anesthetic administration. The Timed-Up-and-Go Test and the 30-Second Chair Stand Test.4,5 aim of this cadaveric study was to identify the trajectory of all nerves that In recent years, an increased interest in expedited care path- course in the adductor canal from their origin to their termination and de- ways and enhanced early mobilization after TKA has driven the scribe their relative contributions to the innervation of the knee joint. search for more peripheral sites of local anesthetic administration Methods: After research ethics board approval, 20 cadaveric lower limbs in an attempt to preserve postoperative quadriceps strength. The were examined using standard dissection technique. Branches of both the adductor canal, also known as the subsartorial or Hunter canal, femoral and obturator nerves were explored along the adductor canal and has been proposed as one such location.6–8 Early data suggest that all branches followed to their termination. -

Lumbar Plexus Block Anatomy

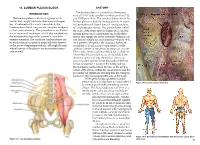

14. LUMBAR PLEXUS BLOCK ANATOMY INTRODUCTION The lumbar plexus is formed from the ventral rami of L1–L4 with variable contributions from T12 The lumbar plexus consists of a group of six and L5 (Figure 14-1). The peripheral branches of the nerves that supply the lower abdomen and upper lumbar plexus include the iliohypogastric, ilioingui- leg. Combined with a sciatic nerve block, the nal, genitofemoral, lateral femoral cutaneous, femo- lumbar plexus block can provide complete analgesia ral, and obturator nerves. The plexus forms within to the lower extremity. This procedure is an alterna- the body of the psoas muscle (Figure 14-2), and the tive to neuraxial anesthesia, which also anesthetizes lumbar plexus block consistently blocks the three the nonoperative leg and occasionally results in nerves that supply the lower extremity (femoral, lat- urinary retention. The complete lumbar plexus can eral femoral cutaneous, and obturator—Figure 14-3). be blocked from a posterior approach (also known As it passes to the pelvis, the obturator has more as the psoas compartment block), although the indi- variability of location and is separated from the vidual nerves of the plexus can be accessed anteri- other two nerves of the plexus by the psoas muscle. orly as well. This is why the femoral nerve block (also called the “3-in-1 block”) often fails to successfully block the obturator nerve and why the lumbar plexus ap- proach is often selected when blockade of all three nerves is required. However, the lumbar plexus block remains controversial because of the deep lo- cation of the plexus within the psoas muscle and the possibility for significant bleeding into the retroperi- toneum in this noncompressible area of the body. -

A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Hip Capsule Innervation and Its Clinical Implications

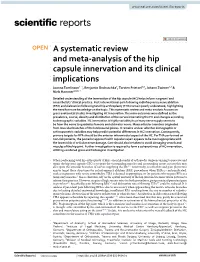

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN A systematic review and meta‑analysis of the hip capsule innervation and its clinical implications Joanna Tomlinson1*, Benjamin Ondruschka2, Torsten Prietzel3,5, Johann Zwirner1,2 & Niels Hammer4,5,6* Detailed understanding of the innervation of the hip capsule (HC) helps inform surgeons’ and anaesthetists’ clinical practice. Post‑interventional pain following radiofrequency nerve ablation (RFA) and dislocation following total hip arthroplasty (THA) remain poorly understood, highlighting the need for more knowledge on the topic. This systematic review and meta‑analysis focuses on gross anatomical studies investigating HC innervation. The main outcomes were defned as the prevalence, course, density and distribution of the nerves innervating the HC and changes according to demographic variables. HC innervation is highly variable; its primary nerve supply seems to be from the nerve to quadratus femoris and obturator nerve. Many articular branches originated from muscular branches of the lumbosacral plexus. It remains unclear whether demographic or anthropometric variables may help predict potential diferences in HC innervation. Consequently, primary targets for RFA should be the anterior inferomedial aspect of the HC. For THA performed on non‑risk patients, the posterior approach with capsular repair appears to be most appropriate with the lowest risk of articular nerve damage. Care should also be taken to avoid damaging vessels and muscles of the hip joint. Further investigation is required to form a coherent map of HC innervation, utilizing combined gross and histological investigation. When performing total hip arthroplasty (THA), one philosophy of orthopedic surgeons aiming to preserve and repair the hip joint capsule (HC) is to spare the surrounding muscles and surrounding tissue, in turn this may also spare the articular branches of nerves supplying the HC 1,2. -

The Anatomy and Clinical Implications of the Obturator Nerve and Its Branches

The anatomy and clinical implications of the obturator nerve and its branches by Zithulele Nkosinathi Tshabalala Dissertation submitted in full fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Anatomy In the Faculty of Health Science University of Pretoria Supervisor: Dr A-N van Schoor Co-supervisor: Mrs R Human-Baron Co-supervisor: Mrs S van der Walt 2015 DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA The Department of Anatomy places great emphasis upon integrity and ethical conduct in the preparation of all written work submitted for academic evaluation. While academic staff teach you about referencing techniques and how to avoid plagiarism, you too have a responsibility in this regard. If you are at any stage uncertain as to what is required, you should speak to your lecturer before any written work is submitted. You are guilty of plagiarism if you copy something from another author’s work (e.g. a book, an article or a website) without acknowledging the source and pass it off as your own. In effect you are stealing something that belongs to someone else. This is not only the case when you copy work word-for-word (verbatim), but also when you submit someone else’s work in a slightly altered form (paraphrase) or use a line of argument without acknowledging it. You are not allowed to use work previously produced by another student. You are also not allowed to let anybody copy your work with the intention of passing if off as his/her work. Students who commit plagiarism will not be given any credit for plagiarised work. -

Lab 5—Gluteal and Posterior Thigh 1 1. Abduction of the Hip Joint Is

Lab 5—Gluteal and Posterior Thigh Muscles; Tendons — Questions 1 of 1 1. Abduction of the hip joint is performed with the aid of: 5. An elderly woman fell at home and fractured the great- A. The iliopsoas, rectus femoris, and sartorius, along with er trochanter of her femur. Which of the following muscles adductor muscles would continue to function normally? B. Gluteus maximus and the hamstring muscles A. Piriformis C. Gluteus medius and minimus, assisted by the sartori- B. Obturator internus us, tensor fasciae latae, and piriformis C. Gluteus medius D. Adductor longus and brevis and the adductor fibers of D. Gluteus maximus the adductor magnus; assisted by the pectineus and the E. Gluteus minimus gracilis E. Piriformis, obturator internus and externus, superior and inferior gemelli, and quadratus femoris, assisted by the gluteus maximus 2. The Piriformis muscle is primarily involved in 6. A 49-year-old Vietnamese man is diagnosed with tu- A. External rotation of the hip joint berculosis. On physical examination, large flocculent B. Abduction of the hip joint masses are noted over the lateral lumbar back, and a C. Hip adduction and knee flexion similar mass is located in the ipsilateral groin. This pattern D. Internal rotation of the hip joint of involvement strongly suggests an abscess tracking E. Thigh extension and knee flexion along which of the following muscles? A. Adductor longus B. Gluteus maximus C. Gluteus minimus D. Piriformis E. Psoas major 3. A 24-year-old woman complains of weakness when 7. An 8-year-old boy returns to your pediatric clinic be- she extends her thigh and rotates it laterally. -

Gluteal Region-I

Gluteal Region-I Dr Garima Sehgal Associate Professor King George’s Medical University UP, Lucknow Intramuscular (IM) gluteal injections are a commonly used method of administering medication within clinical medicine. Learning Objectives By the end of this teaching session on Gluteal region – I all the MBBS 1st year students must be able to: • Enumerate the boundaries of gluteal region • Enumerate the foramina of gluteal region • Describe the cutaneous innervation of gluteal region • Enumerate the structures in the gluteal region (bones, ligaments, muscles, vessels , nerves) • Describe the origin, insertion, nerve supply & actions of gluteal muscles • Name the key muscle of gluteal region • Describe the origin, insertion, nerve supply & actions of short muscles of the gluteal region • Discuss applied anatomy of muscles of gluteal region Gluteal region BOUNDARIES: Superior: Iliac crest S3 Inferior : Gluteal fold (lower limit of rounded buttock) Lateral : Line joining ASIS to front of greater trochanter Medial : natal cleft between buttocks Structures in the Gluteal region • Bones & joints • Ligaments Thickest muscle- • Muscles Gluteus maximus • Vessels • Nerves Thickest nerve Sciatic nerve • Bursae Bones & Joints of the gluteal region • Dorsal surface of sacrum • Coccyx • Gluteal surface of Ilium • Ischium (ischial tuberosity) • Upper end of femur • Posterior aspect of hip joint • Sacrococcygeal & sacroiliac joint Skeletal background features- Gluteal lines on hip bone Skeletal background features- Features on posterior surface of upper -

Chapter 16 – Individual Nerve Blocks of the Lumbar Plexus

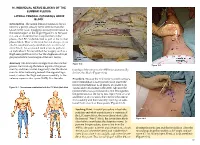

16. INDIVIDUAL NERVE BLOCKS OF THE LUMBAR PLEXUS LATERAL FEMORAL CUTANEOUS NERVE BLOCK Introduction. The lateral femoral cutaneous (LFC) nerve is a purely sensory nerve derived from the L2–L3 nerve roots. It supplies sensory innervation to the lateral aspect of the thigh (Figure 16-1). Because it is one of six nerves that comprise the lumbar plexus, the LFC can be blocked as part of the lumbar plexus block. Most of the time, but not always, it can also be simultaneously anesthetized via a femoral nerve block. An occasional need arises to perform an individual LFC nerve block for surgery such as a thigh skin graft harvest or for the diagnosis of myal- gia paresthetica (a neuralgia of the LFC nerve). Anatomy. The LFC nerve emerges from the lumbar Figure 16-2 Figure 16-3 plexus, travels along the lateral aspect of the psoas muscle, and then crosses diagonally over the iliacus tionship of the nerve to the ASIS that anatomically muscle. After traversing beneath the inguinal liga- defines this block (Figure 16-2). ment, it enters the thigh and passes medially to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). It is the rela- Procedure. Because the LFC nerve is purely sensory, nerve stimulation is not typically used. Insert the needle perpendicular to all planes at a point 2 cm Figure 16-1. Dermatomes anesthetized with the LFC block (dark blue) caudal and 2 cm medial to the ASIS. Advance the needle until a loss-of-resistance is felt; this signifies the penetration of the fascia lata. Inject 5 mL of local anesthetic at this location, then redirect the needle first medially and then laterally, injecting an addi- tional 5 mL at each of these points (Figure 16-3). -

Lower Limb: Gluteal and Thigh Regions

Unit 34: Lower limb: gluteal and thigh regions Chapter 5 (Lower limb): (p. 545-583) GENERAL OBJECTIVES: - Muscles of gluteal and thigh regions of the lower limb - Supply of gluteal and thigh regions of the lower limb SPECIFIC OBJECTIVES: 1. Muscles of gluteal region and thigh Deep Fascia Iliac Fascia Inguinal Ligament --> Pectineal Part (Lacunar Ligament) Fascia Lata --> Iliotibial Tract Intermuscular Septa (3) --> Compartments (3) Muscles of Hip and Thigh Iliac Muscles (From Posterior Abdominal Wall): Psoas Major & Iliacus (-> ‘Ilio-Psoas’) Muscles of Gluteal Region Tensor Fascia Lata Gluteus Maximus Gluteus Medius Gluteus Minimus Piriformis Obturator Internus Superior Gemellus Inferior Gemellus Quadratus Femoris Anterior Compartment of Thigh Sartorius Rectus Femoris,Vastus Lateralis/Medialis/Intermedius(‘Quadriceps’) Pectineus Medial Compartment of Thigh Gracilis Adductor Longus Adductor Brevis Adductor Magnus Obturator Externus Posterior Compartment of Thigh Semitendinosus Semimembranosus Biceps Femoris 2. Topographic anatomy of gluteal region and posterior thigh Boundaries: Roof (Gluteus Maximus) Floor (with Greater and Lesser Sciatic Foraminae) Contents: Sciatic Nerve Other Branches of Sacral Plexus: Superior & Inferior Gluteal Nerves, Posterior Cutaneous Nerve of Thigh Nerves to Obturator Internus & Quadratus Femoris, Pudendal Nerve Superior & Inferior Gluteal Vessels, Internal Pudendal Artery Branches of Medial Circumflex Femoral Artery, Anastomoses around Hip Joint Posterior Compartment of Thigh Sciatic Nerve 3. Topographic anatomy