Three Uses of the Knife

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edmond Press

International Press International Sales Venice: wild bunch The PR Contact Ltd. Venice Phil Symes - Mobile: 347 643 1171 Vincent Maraval Ronaldo Mourao - Mobile: 347 643 0966 Tel: +336 11 91 23 93 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Fax: 041 5265277 Carole Baraton 62nd Mostra Venice Film Festival: Tel: +336 20 36 77 72 Hotel Villa Pannonia Email: [email protected] Via Doge D. Michiel 48 Gaël Nouaile 30126 Venezia Lido Tel: +336 21 23 04 72 Tel: 041 5260162 Email: [email protected] Fax: 041 5265277 Silva Simonutti London: Tel: +33 6 82 13 18 84 The PR Contact Ltd. Email: [email protected] 32 Newman Street London, W1T 1PU Paris: Tel: + 44 (0) 207 323 1200 Wild Bunch Fax: + 44 (0) 207 323 1070 99, rue de la Verrerie - 75004 Paris Email: [email protected] tel: + 33 1 53 01 50 20 fax: +33 1 53 01 50 49 www.wildbunch.biz French Press: French Distribution : Pan Européenne / Wild Bunch Michel Burstein / Bossa Nova Tel: +33 1 43 26 26 26 Fax: +33 1 43 26 26 36 High resolution images are available to download from 32 bd st germain - 75005 Paris the press section at www.wildbunch.biz [email protected] www.bossa-nova.info Synopsis Cast and Crew “You are not where you belong.” Edmond: William H. Macy Thus begins a brutal descent into a contemporary urban hell Glenna: Julia Stiles in David Mamet's savage black comedy, when his encounter B-Girl: Denise Richards with a fortune-teller leads businessman Edmond (William H. -

Ebook Download the Plays, Screenplays and Films of David

THE PLAYS, SCREENPLAYS AND FILMS OF DAVID MAMET PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Steven Price | 192 pages | 01 Oct 2008 | MacMillan Education UK | 9780230555358 | English | London, United Kingdom The Plays, Screenplays and Films of David Mamet PDF Book It engages with his work in film as well as in the theatre, offering a synoptic overview of, and critical commentary on, the scholarly criticism of each play, screenplay or film. You get savvy industry tips and strategies for getting your screenplay noticed! Mamet is reluctant to be specific about Postman and the problems he had writing it, explaining. He shrugs off the whispers floating up and down the Great White Way about him selling out and going Hollywood. Contemporary playwright David Mamet's thought-provoking plays and screenplays such as Wag the Dog , Glengarry Glen Ross for which he won the Pulitzer Prize , and Oleanna have enjoyed popular and critical success in the past two decades. The Winslow Boy, Mamet's revisitation of Terence Rattigan's classic play, tells of a thirteen-year-old boy accused of stealing a five-shilling postal order and the tug of war for truth that ensues between his middle-class family and the Royal Navy. House of Games is a psychological thriller in which a young woman psychiatrist falls prey to an elaborate and ingenious con game by one of her patients who entraps her in a series of criminal escapades. Paul Newman plays Frank Calvin, an alcoholic and disgraced Boston lawyer who finds a shot at redemption with a malpractice case. I Just Kept Writing. The impressive number of essays , novels , screenplays , and films that Mamet has produced They might be composed and awesome on the battlefield, but there is a price, and that is their humanity. -

Transcript Sidney Lumet

TRANSCRIPT A PINEWOOD DIALOGUE WITH SIDNEY LUMET Sidney Lumet’s critically acclaimed 2007 film Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, a dark family comedy and crime drama, was the latest triumph in a remarkable career as a film director that began 50 years earlier with 12 Angry Men and includes such classics as Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon, and Network. This tribute evening included remarks by the three stars of Before the Devil Knows Your Dead, Ethan Hawke, Marissa Tomei, and Philip Seymour Hoffman, and a lively conversation with Lumet about his many collaborations with great actors and his approach to filmmaking. A Pinewood Dialogue with Sidney Lumet shooting, “I feel that there’s another film crew on moderated by Chief Curator David Schwartz the other side of town with the same script and a (October 25, 2007): different cast, and we’re trying to beat them.” (Laughter) “You know, trying to wrap the movie DAVID SCHWARTZ: (Applause) Thank you, and ahead of them. It’s like a race.” I remember welcome, everybody. Sidney Lumet, as I think all saying that “you know if this movie works, then of you know, has received a number of salutes I’m going to have to rethink my whole idea of and awards over the years that could be process, because I can not imagine that this will considered lifetime achievement awards—which work!” (Laughter) I’ve never seen such a might sometimes imply that they’re at the end of deliberate—I’m going to steal your words, Phil, their career. But that’s certainly far from the case, but—a focus of energy, and use of energy. -

David Mamet - Edited by Christopher Bigsby Excerpt More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521894689 - The Cambridge Companion to David Mamet - Edited by Christopher Bigsby Excerpt More information 1 CHRISTOPHER BIGSBY David Mamet In 1974, a play set in part in a singles bar, laced with obscene language and charged with a seemingly frenetic energy, was voted Best Chicago Play. Transferred to Off Off and Off Broadway it picked up an Obie Award. Sexual Perversity in Chicago was not David Mamet’s first play, but it did mark the beginning of a career that would astonish in both its range and depth. The following year American Buffalo opened at Chicago’s Goodman The- atre in an “alternative season.” It was well received and opened on Broadway fifteen months later where it won the New York Drama Critics Circle Award. It ran for 135 performances, hardly a failure but in the hit or miss world of New York, not a copper-bottomed success either. Nonetheless, in three years he had announced his arrival in unequivocal terms. David Mamet came as something of a shock, not least because his first public success, Sexual Perversity in Chicago, seemed brutally direct in terms of its language and subject, as did American Buffalo. But it was already clear to many that here was a distinctive talent, albeit one that some critics found difficult to assess, not least because of his characters’ scatological language and fractured syntax, along with the apparent absence, in his plays, of a conventional plot. They praised what they took to be his linguistic naturalism, as though his intent had been to offer an insight into the cultural lower depths while capturing the precise rhythms of contemporary speech (though he did invoke Gorky’s The Lower Depths as being, like a number of his own plays, a study in stasis). -

David Mamet in Conversation

David Mamet in Conversation David Mamet in Conversation Leslie Kane, Editor Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2001 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ∞ Printed on acid-free paper 2004 2003 2002 2001 4 3 2 1 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data David Mamet in conversation / Leslie Kane, editor. p. cm. — (Theater—theory/text/performance) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-472-09764-4 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-472-06764-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Mamet, David—Interviews. 2. Dramatists, American—20th century—Interviews. 3. Playwriting. I. Kane, Leslie, 1945– II. Series. PS3563.A4345 Z657 2001 812'.54—dc21 [B] 2001027531 Contents Chronology ix Introduction 1 David Mamet: Remember That Name 9 Ross Wetzsteon Solace of a Playwright’s Ideals 16 Mark Zweigler Buffalo on Broadway 22 Henry Hewes, David Mamet, John Simon, and Joe Beruh A Man of Few Words Moves On to Sentences 27 Ernest Leogrande I Just Kept Writing 31 Steven Dzielak The Postman’s Words 39 Dan Yakir Something Out of Nothing 46 Matthew C. Roudané A Matter of Perception 54 Hank Nuwer Celebrating the Capacity for Self-Knowledge 60 Henry I. Schvey Comics -

American Repertory Theater Presents ROMANCE by David Mamet

News Release April 23, 2009 Contact: Kati Mitchell 617-496-2000 x8841 American Repertory Theater presents ROMANCE by David Mamet directed by Scott Zigler WHAT: American Repertory Theater presents David Mamet’s Romance, a courtroom farce that takes no prisoners in its quest for total political incorrectness. WHEN: May 9 - June 7, 2009 Tues–Thurs, Sun @ 7:30pm; Fri–Sat @ 8:00pm; Sat & Sun matinees @ 2:00pm Opening Night/Press Review Night: Wednesday, May 13 @ 7:30pm WHERE: Loeb Drama Center, 64 Brattle Street, Cambridge TICKETS: $25-79. Student discounts include single tickets at $25 advance purchase, and $15 day of performance. Other discounts include 50 @ 15 at noon ($15 tickets on sale at noon on the day of performance; in person only, based on availability) and Pay What You Can (50 tickets available for every Saturday matinee performance of the season at the Loeb Drama Center for patrons to purchase at whatever amount they can afford (based on availability). Group rates, with extra savings for senior citizens and student groups are also available. Tickets can be purchased online at www.americanrepertorytheater.org, by phone at 617-547-8300, or in person at the A.R.T. Box office. RATING: “R” — Ridiculous, Rude, Raunchy, Raucous. SOUNDBITE: “A Jewish chiropractor, a Catholic defense lawyer, a gay prosecutor, and a pill-popping judge walk into a courtroom... “ It's ROMANCE...Mamet-style CRITICAL ACCLAIM: “ A joy — a fiesta of forbidden laughter...glorious.” – Newsday “...an exhilarating spectacle. Mamet is a connoisseur of fiasco, knows all abut legal punctilio, and has great fun bringing mayhem to the ritual.” The New Yorker “It made me weep with delight. -

Adaptive Collaboration, Collaborative Adaptation: Filming the Mamet Canon

Adaptation Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 82–98 doi: 10.1093/adaptation/apq004 Advance Access publication 8 April 2010 Adaptive Collaboration, Collaborative Adaptation: Filming the Mamet Canon CHRISTOPHE COLLARD* Downloaded from Abstract Every migration across referential and expressive frameworks entails formal, struc- tural, and cognitive consequences too complex for a ‘traditionalist’ comparative posture. More- over, the intertextuality and intermediality of the ‘transmedial screenplay’ make it incompatible with ‘static’ concepts such as ‘fidelity’ and ‘originality’ precisely on behalf of the film medium’s adaptation.oxfordjournals.org poly-systemic nature. Bringing together the analogous concerns of collaborative creation, adap- tation, and authorship, this essay therefore discusses David Mamet’s screen adaptations of per- sonal and other work from a process-based perspective as a means of attaining a more constructive understanding of so-called ‘interaesthetic passages’. Keywords David Mamet, collaborative creation, adaptation, authorship, semiology. at Funda??o Coordena??o de Aperfei?oamento Pessoal N?vel Superior on June 3, 2011 All train compartments smell vaguely of shit. It gets so you don’t mind it. That’s the worst thing that I can confess. (Mamet, Glengarry Glen Ross) INTRODUCTION Every single film producer, Hollywood veteran Art Linson has claimed, knows that at the inception of the movie-making process stands ‘an idea’ derived from ‘A book. A play. A song. A news event. A magazine article. A historic event or character. A personal experience. -

David Mamet's Drama, Glengarry Glen Ross, and Three Iconic Forerunners

Ad Americam. Journal of American Studies 20 (2019): 5-14 ISSN: 1896-9461, https://doi.org/10.12797/AdAmericam.20.2019.20.01 Robert J. Cardullo University of Kurdistan, Hewlêr [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0816-9751 The Death of Salesmen: David Mamet’s Drama, Glengarry Glen Ross, and Three Iconic Forerunners This essay places Glengarry Glen Ross in the context of David Mamet’s oeuvre and the whole of American drama, as well as in the context of economic capitalism and even U.S. for- eign policy. The author pays special attention here (for the first time in English-language scholarship) to the subject of salesmen or selling as depicted in Mamet’s drama and earlier in Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh, and Tennes- see Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire—each of which also features a salesman among its characters. Key words: David Mamet; Glengarry Glen Ross; American drama; Selling/salesmanship; Americanism; Death of a Salesman; The Iceman Cometh; A Streetcar Named Desire. Introduction: David Mamet’s Drama This essay will first placeGlengarry Glen Ross (1983) in the context of David Mamet’s oeuvre and then discuss the play in detail, before going on to treat the combined subject of salesmen or selling, economic capitalism, and even U.S. foreign policy as they are depicted or intimated not only in Glengarry but in earlier American drama (a subject previously undiscussed in English-language scholarship). I am thinking here of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman (1949), Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Co- meth (1946), and Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire (1947)—each of which also features a salesman among its main characters. -

Cambridge Marriage: Mamet at the A.R.T

far left: William H. Macy and David Mamet in rehearsal for Mamet’s Oleanna, photo: Brigitte Cambridge Marriage: Lacombe; bottom left: Felicity Huffman and Shelton Dane in the A.R.T.’s production of The Crytogram, photo: Henry Horenstein; left: Felicity Huffman and Rebecca Pidgeon in the Mamet at the A.R.T. A.R.T.’s production of Boston Marriage, photo: Richard Feldman; below: Brooke Adams and Tony Shalhoub in the A.R.T.’s production of The By Sean Bartley Old Neighborhood, photo: Richard Feldman Times and engaged academics in heated of the most fascinating women on the debate. No other Mamet play has inspired contemporary American stage. As Felicity critics to spill so much ink. Huffman, who played the mother, told the After a performance, a female student Boston Herald: asked the playwright whose side he was on, the strutting macho professor’s or “He writes difficult, challenging roles the guerilla feminist’s. “I’m an artist,” for women, but he also writes difficult, Mamet replied. “I write plays, not political challenging roles for men. No one’s the propaganda. If you want easy solutions, hero. There wasn’t a hero in The Cryp- turn on the boob tube. Social and political togram, but it has a brilliant part for a issues on TV are cartoons; the good guy woman. No one’s the hero in Speed-the- wears a white hat, the bad guy a black hat. Plow. He gives his women, along with Cartoons don’t interest me.” the men, really difficult jobs to do, and DAVID MAMET’S MARRIAGE with the “I write plays, not political propaganda. -

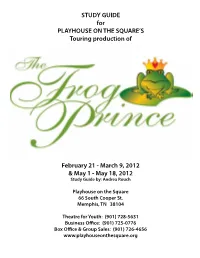

STUDY GUIDE for PLAYHOUSE on the SQUARE's

STUDY GUIDE for PLAYHOUSE ON THE SQUARE’S Touring production of February 21 - March 9, 2012 & May 1 - May 18, 2012 Study Guide by: Andrea Rouch Playhouse on the Square 66 South Cooper St. Memphis, TN 38104 Theatre for Youth: (901) 728-5631 Business Office: (901) 725-0776 Box Office & Group Sales: (901) 726-4656 www.playhouseonthesquare.org table of contents Part One: The Play.................................................................1 Synopsis................................................................................................................................................1 Vocabulary...................................................................................................................................................2 Part Two: Background...........................................................3 About the Playwright......................................................................................................................3 Origins of the Play..............................................................................................................................3 About Brothers Grimm....................................................................................................................4 Part Three: Activities and Discussion.................................5 Before Seeing the Play...................................................................................................................5 After Seeing the Play......................................................................................................................5 -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Dafina Mcmillan January 16, 2013 [email protected] 212-609-5955

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Dafina McMillan January 16, 2013 [email protected] 212-609-5955 New from TCG Books: The Anarchist by David Mamet NEW YORK, NY – Theatre Communications Group (TCG) is pleased to announce the publication of the newest play by Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright David Mamet: The Anarchist. Just having completed its world premiere on Broadway under the direction of the playwright and starring Patti LuPone and Debra Winger, Mr. Mamet’s work is also currently represented on Broadway with the revival of his award-winning Glengarry Glen Ross starring Al Pacino and Bobby Cannavale. “Mamet remains the American theatre’s most urgent five-letter word.” ― Guardian (London) Nothing is quite what it seems in Mamet’s latest work. Set in a female penitentiary, David Mamet's two-woman drama is about Cathy, a longtime inmate with ties to a violent political organization, who pleads for parole from the warden, Ann. With a nod to his mentor, Harold Pinter, Mamet once again employs his signature verbal jousting in this battle of two women over freedom, power, money, religion – and the lack thereof. “Students of Mamet won’t want to miss it. I was engaged and compelled throughout. Indeed, The Anarchist is a counterweight to the conventional dramatic tropes of family, love and death.” ― Chicago Tribune David Mamet is a playwright, essayist and screenwriter who directs for both the stage and film. He was awarded the Pulitzer Prize and New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award for Glengarry Glen Ross. His other plays include Race, American Buffalo, Speed-the-Plow, November, The Cryptogram, Sexual Perversity in Chicago, Lakeboat, The Water Engine, The Duck Variations, Reunion, The Blue Hour, The Shawl, Bobby Gould in Hell, Edmond, Romance, The Old Neighborhood and his adaptation of The Voysey Inheritance. -

Liener Temerlin Zooms Off on a Segway | Dallas Morning News | News For…Llas, Texas | Lifestyles Columnist Alan Peppard | Dallas Morning News 3/17/08 6:21 AM

Liener Temerlin zooms off on a Segway | Dallas Morning News | News for…llas, Texas | Lifestyles Columnist Alan Peppard | Dallas Morning News 3/17/08 6:21 AM Liener Temerlin zooms off on a Segway 12:00 AM CDT on Monday, March 17, 2008 By ALAN PEPPARD / The Dallas Morning News [email protected] Segway inventor Dean Kamen needs to send a fleet of his gyroscopically stabilized transporters to Dallas advertising executive Liener Temerlin and make him the company's new spokesman. Liener is the founder of the AFI Dallas International Film Festival. Last week, AFI Dallas had a party at the Current Energy store on Knox Street. In 10 days, Liener will be 80 years old. But after a short lesson from Current Energy co-founder Joseph Harberg, Liener was up and riding one of the store's Segways and proclaiming that he wanted to buy a couple. Among those on hand for the gathering were Dallas Film Commission director Janis Burklund; director Russ Pond, who will show his film Fissure at AFI Dallas; AFI Dallas board members Stephanie and Hunter Hunt; and literary agent David Hale Smith. Preparing for Mamet When playwright and filmmaker David Mamet gives the keynote address at the Dallas Institute's Hiett Prize dinner on April 8, he will face a uniquely prepared audience. As a prelude to the event, the Dallas Institute of Humanities and Culture is presenting a two- session series, "Dark and Light: The Genius of David Mamet" on March 18 and April 1. University of Dallas drama chairman Patrick Kelly and book and stage critic Jerome Weeks will lead the discussions.