BECKET by Jean Anouilh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jerold Frederic Presents Concert of Gripping Music Philharmonic

THE% ECHO VOL. XXV TAYLOR UNIVERSITY, UPLAND, INDIANA, SATURDAY. FEBRUARY 5, 1938 NO. 9 Judge Fred Bale Jerold Frederic Mystery Abounds Philharmonic Orchestra Coming Discusses Vital Presents Concert When Dramatists Issues at T. U. Of Gripping Music Thrill Audience All Taylor music lovers were A phantom tiger, a death light, thrilled at the masterful playing a haunted house, a terrific storm of Jehold Frederic as he was pre — an ideal setting for a mystery! sented by the Lyceum Committee, In Spiers Hall on January 29th Tuesday evening, January 18th, one of the hit programs of the in Shreiner Auditorium. year was the presentation of His graduation from the "Tiger House", Robert St. Clair's thundering londs to the soft, popular three act. novel comedy. sweet passages, his brilliant tech In the minds of the audience nique, excellent tone quality and which crowded the little audi keen sense of rhythm held the torium to its capacity, the play audience enthralled during the | ranks high among Taylor's Magic of Murdock G. H. Shapiro and entire program. His powerful, literary productions. No one was His Orchestra to yet gentle fingers brought forth disappointed in the thrilling en Provides Thrills his notable creative ability in his tertainment. Appear at Taylor interpretation of Chopin. His Weird fantastical sounds, For Large Group presentation of Liszt himself, tricky movable panels, cruel On February 19, the Lyceum rather than his music, it was as | clutching claws! Was it any Even the "front" seats of Committee is presenting the next if his listeners were for the time wonder onlookers sat on the Shreiner Auditorium were oc in the series of programs. -

Classics 3: Program Notes Overture to Candide Leonard Bernstein Born in Lawrence, Massachusetts, August 25, 1918

Classics 3: Program Notes Overture to Candide Leonard Bernstein Born in Lawrence, Massachusetts, August 25, 1918; died in New York, October 14, 1990 After collaborating on The Lark, a play with incidental music about Joan of Arc, Leonard Bernstein and Lillian Hellman turned their attention in 1954 to Voltaire’s novella Candide. They thought it the perfect vehicle to make an artistic statement against political intolerance in American society, just as Voltaire had done in eighteenth-century France. After bringing in poet Richard Wilbur to write the lyrics, they worked intermittently on Candide for two years. Enormous amounts of money were spent on the production, which opened in Boston on October 29, 1956. Though many critics called it brilliant, the production failed financially; after moving to New York in December, it was shut down after just seventy-three performances. Everyone had someone to blame, but many thought it failed because of audience confusion about its hybrid nature—was it an opera, operetta, or a musical? Leonard Bernstein: celebrating his The story revolves around the illegitimate Candide, who centennial loves and is loved in return by Cunegonde, daughter of nobility. They are plagued by myriad disasters, which lead them from Westphalia to Lisbon, Paris, Cadiz, Buenos Aires, Eldorado, Surinam, and finally Venice, where they are united at last. Bernstein’s often witty, sometimes tender music has been considered the work’s greatest asset, both in the initial failed production and in later successful versions. The Overture, possibly Bernstein’s most frequently performed piece, perfectly captures the mockery and satire as well as the occasional introspective moment of Voltaire’s masterful creation. -

Surviving Antigone: Anouilh, Adaptation, and the Archive

SURVIVING ANTIGONE: ANOUILH, ADAPTATION AND THE ARCHIVE Katelyn J. Buis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2014 Committee: Cynthia Baron, Advisor Jonathan Chambers ii ABSTRACT Dr. Cynthia Baron, Advisor The myth of Antigone has been established as a preeminent one in political and philosophical debate. One incarnation of the myth is of particular interest here. Jean Anouilh’s Antigone opened in Paris, 1944. A political and then philosophical debate immediately arose in response to the show. Anouilh’s Antigone remains a well-known play, yet few people know about its controversial history or the significance of its translation into English immediately after the war. It is this history and adaptation of Anouilh’s contested Antigone that defines my inquiry. I intend to reopen interpretive discourse about this play by exploring its origins, its journey, and the archival limitations and motivations controlling its legacy and reception to this day. By creating a space in which multiple readings of this play can exist, I consider adaptation studies and archival theory and practice in the form of theatre history, with a view to dismantle some of the misconceptions this play has experienced for over sixty years. This is an investigation into the survival of Anouilh’s Antigone since its premiere in 1944. I begin with a brief overview of the original performance of Jean Anouilh’s Antigone and the significant political controversy it caused. The second chapter centers on the changing reception of Anouilh’s Antigone beginning with the liberation of Paris to its premiere on the Broadway stage the following year. -

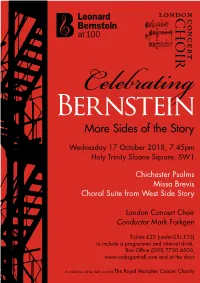

Bernsteincelebrating More Sides of the Story

BernsteinCelebrating More Sides of the Story Wednesday 17 October 2018, 7.45pm Holy Trinity Sloane Square, SW1 Chichester Psalms Missa Brevis Choral Suite from West Side Story London Concert Choir Conductor Mark Forkgen Tickets £25 (under-25s £15) to include a programme and interval drink. Box Office (020) 7730 4500, www.cadoganhall.com and at the door A collection will be held in aid of The Royal Marsden Cancer Charity One of the most talented and successful musicians in American history, Leonard Bernstein was not only a composer, but also a conductor, pianist, educator and humanitarian. His versatility as a composer is brilliantly illustrated in this concert to celebrate the centenary of his birth. The Dean of Chichester commissioned the Psalms for the 1965 Southern Cathedrals Festival with the request that the music should contain ‘a hint of West Side Story.’ Bernstein himself described the piece as ‘forthright, songful, rhythmic, youthful.’ Performed in Hebrew and drawing on jazz rhythms and harmonies, the Psalms Music Director: include an exuberant setting of ‘O be joyful In the Lord all Mark Forkgen ye lands’ (Psalm 100) and a gentle Psalm 23, ‘The Lord is my shepherd’, as well as some menacing material cut Nathan Mercieca from the score of the musical. countertenor In 1988 Bernstein revisited the incidental music in Richard Pearce medieval style that he had composed in 1955 for organ The Lark, Anouilh’s play about Joan of Arc, and developed it into the vibrant Missa Brevis for unaccompanied choir, countertenor soloist and percussion. Anneke Hodnett harp After three contrasting solo songs, the concert is rounded off with a selection of favourite numbers from Sacha Johnson and West Side Story, including Tonight, Maria, I Feel Pretty, Alistair Marshallsay America and Somewhere. -

ARSC Journal

LEONARD BERNSTEIN, A COMPOSER DISCOGRAPHY" Compiled by J. F. Weber Sonata for clarinet and piano (1941-42; first performed 4-21-42) David Oppenheim, Leonard Bernstein (recorded 1945) (78: Hargail set MW 501, 3ss.) Herbert Tichman, Ruth Budnevich (rec. c.1953} Concert Hall Limited Editions H 18 William Willett, James Staples (timing, 9:35) Mark MRS 32638 (released 12-70, Schwann) Stanley Drucker, Leonid Hambro (rec. 4-70) (10:54) Odyssey Y 30492 (rel. 5-71) (7) Anniversaries (for piano) (1942-43) (2,5,7) Leonard Bernstein (o.v.) (rec. 1945) (78: Hargail set MW 501, ls.) (1,2,3) Leonard Bernstein (rec. c.1949) (4:57) (78: RCA Victor 12 0683 in set DM 1278, ls.) Camden CAL 214 (rel. 5-55, del. 2-58) (4,5) Leonard Bernstein (rec. c.1949) (3:32) (78: RCA Victor 12 0228 in set DM 1209, ls.) (vinyl 78: RCA Victor 18 0114 in set DV 15, ls.) Camden CAL 214 (rel. 5-55, del. 2-58); CAL 351 (6,7) Leonard Bernstein (rec. c.1949) (2:18) Camden CAL 214 (rel. 5-55, del. 2-58); CAL 351 Jeremiah symphony (1941-44; f.p. 1-28-44) Nan Merriman, St. Louis SO--Leonard Bernstein (rec. 12-1-45) ( 23: 30) (78: RCA Victor 11 8971-3 in set DM 1026, 6ss.) Camden CAL 196 (rel. 2-55, del. 6-60) "Single songs from tpe Broadway shows and arrangements for band, piano, etc., are omitted. Thanks to Jane Friedmann, CBS; Peter Dellheim, RCA; Paul de Rueck, Amberson Productions; George Sponhaltz, Capitol; James Smart, Library of Congress; Richard Warren, Jr., Yael Historical Sound Recordings; Derek Lewis, BBC. -

Christopher Plummer

Christopher Plummer "An actor should be a mystery," Christopher Plummer Introduction ........................................................................................ 3 Biography ................................................................................................................................. 4 Christopher Plummer and Elaine Taylor ............................................................................. 18 Christopher Plummer quotes ............................................................................................... 20 Filmography ........................................................................................................................... 32 Theatre .................................................................................................................................... 72 Christopher Plummer playing Shakespeare ....................................................................... 84 Awards and Honors ............................................................................................................... 95 Christopher Plummer Introduction Christopher Plummer, CC (born December 13, 1929) is a Canadian theatre, film and television actor and writer of his memoir In "Spite of Myself" (2008) In a career that spans over five decades and includes substantial roles in film, television, and theatre, Plummer is perhaps best known for the role of Captain Georg von Trapp in The Sound of Music. His most recent film roles include the Disney–Pixar 2009 film Up as Charles Muntz, -

JEAN ANOUILH the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Tru St

, .. ., ...I I I 1 • ,,~- • i' JEAN ANOUILH The Australian Elizabethan Theatre Tru st when you fly with Trans-AustraliaAirlines PAT RON : H ER MAJESTY T H E QUEE N P RE SIDE T The Rt. H on . Sir John Latham, G.C.M.G., Q .C. CH AIRM A1 Dr. H . C. Coombs EXECUTIVE Dffi ECTOR Hu gh Hunt HO . SECRETARY :l,faurire Parker STATE REPRESE , TAT JVES: , ew South \,Vales Mr. C. J. A. lvloscs, C.B .E. Qu eensland Prof esso r F. J . Schone II Western Australia Pr ofessor F. Alexander Victoria Mr . A . H. L. Gibson Sou tit Australia Mr. L. C. Waterm an Tasmania Mr . G. F. Davies In presenting TIME REMEMBERED , we are paying tribute to a dramatist whose contribution to the contemporary theatre scene is a11 outstanding one and whose influence has been most strongly felt during the post-war years in Europe. The J1lays of Jean An ouilh have not been widely produced in Cao raln and First Officer at the co mrol s of a TA A Viscount . Australia , and his masterly qualities as a playwright are not TAA pilots are well experi years of flying the length and sufficiently k11011·n. enced and maintain a high breadth of Australia. standard of efficiency in flying TAA 's Airmanship is the total TIME REME1vlBERED htippily contains some of the the nation's finest fleet of skill of many people-in the most typical aspects of his work . .. a sense of the comic, modern aircraft. air and on the ground-w ork ing toward s a common goal: almost biza1'1'e,and tl haunting nostalgia which together pro When you and your family fly your safety, satisfaction and T AA, you get with your ticket peace of mind. -

ANTA Theater and the Proposed Designation of the Related Landmark Site (Item No

Landmarks Preservation Commission August 6, 1985; Designation List 182 l.P-1309 ANTA THFATER (originally Guild Theater, noN Virginia Theater), 243-259 West 52nd Street, Manhattan. Built 1924-25; architects, Crane & Franzheim. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1024, Lot 7. On June 14 and 15, 1982, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the ANTA Theater and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 5). The hearing was continued to October 19, 1982. Both hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Eighty-three witnesses spoke in favor of designation. Two witnesses spoke in opposition to designation. The owner, with his representatives, appeared at the hearing, and indicated that he had not formulated an opinion regarding designation. The Commission has received many letters and other expressions of support in favor of this designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The ANTA Theater survives today as one of the historic theaters that symbolize American theater for both New York and the nation. Built in the 1924-25, the ANTA was constructed for the Theater Guild as a subscription playhouse, named the Guild Theater. The fourrling Guild members, including actors, playwrights, designers, attorneys and bankers, formed the Theater Guild to present high quality plays which they believed would be artistically superior to the current offerings of the commercial Broadway houses. More than just an auditorium, however, the Guild Theater was designed to be a theater resource center, with classrooms, studios, and a library. The theater also included the rrost up-to-date staging technology. -

Composition Catalog

1 LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 New York Content & Review Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. Marie Carter Table of Contents 229 West 28th St, 11th Floor Trudy Chan New York, NY 10001 Patrick Gullo 2 A Welcoming USA Steven Lankenau +1 (212) 358-5300 4 Introduction (English) [email protected] Introduction 8 Introduction (Español) www.boosey.com Carol J. Oja 11 Introduction (Deutsch) The Leonard Bernstein Office, Inc. Translations 14 A Leonard Bernstein Timeline 121 West 27th St, Suite 1104 Straker Translations New York, NY 10001 Jens Luckwaldt 16 Orchestras Conducted by Bernstein USA Dr. Kerstin Schüssler-Bach 18 Abbreviations +1 (212) 315-0640 Sebastián Zubieta [email protected] 21 Works www.leonardbernstein.com Art Direction & Design 22 Stage Kristin Spix Design 36 Ballet London Iris A. Brown Design Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Limited 36 Full Orchestra Aldwych House Printing & Packaging 38 Solo Instrument(s) & Orchestra 71-91 Aldwych UNIMAC Graphics London, WC2B 4HN 40 Voice(s) & Orchestra UK Cover Photograph 42 Ensemble & Chamber without Voice(s) +44 (20) 7054 7200 Alfred Eisenstaedt [email protected] 43 Ensemble & Chamber with Voice(s) www.boosey.com Special thanks to The Leonard Bernstein 45 Chorus & Orchestra Office, The Craig Urquhart Office, and the Berlin Library of Congress 46 Piano(s) Boosey & Hawkes • Bote & Bock GmbH 46 Band Lützowufer 26 The “g-clef in letter B” logo is a trademark of 47 Songs in a Theatrical Style 10787 Berlin Amberson Holdings LLC. Deutschland 47 Songs Written for Shows +49 (30) 2500 13-0 2015 & © Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. 48 Vocal [email protected] www.boosey.de 48 Choral 49 Instrumental 50 Chronological List of Compositions 52 CD Track Listing LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 2 3 LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 A Welcoming Leonard Bernstein’s essential approach to music was one of celebration; it was about making the most of all that was beautiful in sound. -

Leonard Bernstein

chamber music with a modernist edge. His Piano Sonata (1938) reflected his Leonard Bernstein ties to Copland, with links also to the music of Hindemith and Stravinsky, and his Sonata for Clarinet and Piano (1942) was similarly grounded in a neoclassical aesthetic. The composer Paul Bowles praised the clarinet sonata as having a "tender, sharp, singing quality," as being "alive, tough, integrated." It was a prescient assessment, which ultimately applied to Bernstein’s music in all genres. Bernstein’s professional breakthrough came with exceptional force and visibility, establishing him as a stunning new talent. In 1943, at age twenty-five, he made his debut with the New York Philharmonic, replacing Bruno Walter at the last minute and inspiring a front-page story in the New York Times. In rapid succession, Bernstein Leonard Bernstein photo © Susech Batah, Berlin (DG) produced a major series of compositions, some drawing on his own Jewish heritage, as in his Symphony No. 1, "Jeremiah," which had its first Leonard Bernstein—celebrated as one of the most influential musicians of the performance with the composer conducting the Pittsburgh Symphony in 20th century—ushered in an era of major cultural and technological transition. January 1944. "Lamentation," its final movement, features a mezzo-soprano He led the way in advocating an open attitude about what constituted "good" delivering Hebrew texts from the Book of Lamentations. In April of that year, music, actively bridging the gap between classical music, Broadway musicals, Bernstein’s Fancy Free was unveiled by Ballet Theatre, with choreography by jazz, and rock, and he seized new media for its potential to reach diverse the young Jerome Robbins. -

BEYOND the BASICS Supplemental Programming for Leonard Bernstein at 100

BEYOND THE BASICS Supplemental Programming for Leonard Bernstein at 100 BEYOND THE BASICS – Contents Page 1 of 37 CONTENTS FOREWORD ................................................................................. 4 FOR FULL ORCHESTRA ................................................................. 5 Bernstein on Broadway ........................................................... 5 Bernstein and The Ballet ......................................................... 5 Bernstein and The American Opera ........................................ 5 Bernstein’s Jazz ....................................................................... 6 Borrow or Steal? ...................................................................... 6 Coolness in the Concert Hall ................................................... 7 First Symphonies ..................................................................... 7 Romeos & Juliets ..................................................................... 7 The Bernstein Beat .................................................................. 8 “Young Bernstein” (working title) ........................................... 9 The Choral Bernstein ............................................................... 9 Trouble in Tahiti, Paradise in New York .................................. 9 Young People’s Concerts ....................................................... 10 CABARET.................................................................................... 14 A’s and B’s and Broadway .................................................... -

Sophocles' Elektra

DATE: August 12, 2010 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ABOUT THE COMPANY Sophocles' Elektra Thursdays, Fridays, Saturdays, September 9—October 2, 2010 Carey Perloff (Director) Carey Perloff is celebrating her nineteenth season as artistic director of Tony Award-winning American Conservatory Theater (A.C.T.) in San Francisco, where she is known for directing innovative productions of classics, championing new writing for the theater, and creating international collaborations with such artists as Robert Wilson and Tom Stoppard. Before joining A.C.T., Perloff was artistic director of Classic Stage Company (CSC) in New York. She is a recipient of France’s Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres and the National Corporate Theatre Fund’s 2007 Artistic Achievement Award. Perloff received a B.A. Phi Beta Kappa in classics and comparative literature from Stanford University and was a Fulbright fellow at the University of Oxford. She has taught at the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University and in the Master of Fine Arts Program in Acting at A.C.T., in addition to authoring numerous plays. This is Perloff’s second encounter with Sophocles’ Elektra, having directed the world premiere of Ezra Pound’s version of the play at CSC in 1988. Timberlake Wertenbaker (Translator/Adaptor) Timberlake Wertenbaker is an acclaimed playwright who grew up in the Basque Country in southwest France. Plays include The Grace of Mary Traverse (Royal Court Theatre); Our Country's Good (Royal Court Theatre and Broadway), which won the Laurence Olivier Play of the Year