Exotic Yet Often Colourless the Imported Place Names Ofkwazulu-Natal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ETHEKWINI MEDICAL HEALTH Facilitiesmontebellomontebello Districtdistrict Hospitalhospital CC 88 MONTEBELLOMONTEBELLO

&& KwaNyuswaKwaNyuswaKwaNyuswa Clinic ClinicClinic MontebelloMontebello DistrictDistrict HospitalHospital CC 88 ETHEKWINI MEDICAL HEALTH FACILITIESMontebelloMontebello DistrictDistrict HospitalHospital CC 88 MONTEBELLOMONTEBELLO && MwolokohloMwolokohlo ClinicClinic (( NdwedweNdwedweNdwedwe CHC CHCCHC && GcumisaGcumisa ClinicClinic CC MayizekanyeMayizekanye ClinicClinic BB && && ThafamasiThafamasiThafamasi Clinic ClinicClinic WosiyaneWosiyane ClinicClinic && HambanathiHambanathiHambanathi Clinic ClinicClinic && (( TongaatTongaatTongaat CHC CHCCHC CC VictoriaVictoriaVictoria Hospital HospitalHospital MaguzuMaguzu ClinicClinic && InjabuloInjabuloInjabuloInjabulo Clinic ClinicClinicClinic A AAA && && OakfordOakford ClinicClinic OsindisweniOsindisweni DistrictDistrict HospitalHospital CC EkukhanyeniEkukhanyeniEkukhanyeni Clinic ClinicClinic && PrimePrimePrime Cure CureCure Clinic ClinicClinic && BuffelsdraaiBuffelsdraaiBuffelsdraai Clinic ClinicClinic && RedcliffeRedcliffeRedcliffe Clinic ClinicClinic && && VerulamVerulamVerulam Clinic ClinicClinic && MaphephetheniMaphephetheni ClinicClinic AA &’&’ ThuthukaniThuthukaniThuthukani Satellite SatelliteSatellite Clinic ClinicClinic TrenanceTrenanceTrenance Park ParkPark Clinic ClinicClinic && && && MsunduzeMsunduze BridgeBridge ClinicClinic BB && && WaterlooWaterloo ClinicClinic && UmdlotiUmdlotiUmdloti Clinic ClinicClinic QadiQadi ClinicClinic && OttawaOttawa ClinicClinic && &&AmatikweAmatikweAmatikwe Clinic ClinicClinic && CanesideCanesideCaneside Clinic ClinicClinic AmaotiAmaotiAmaoti Clinic -

From Mission School to Bantu Education: a History of Adams College

FROM MISSION SCHOOL TO BANTU EDUCATION: A HISTORY OF ADAMS COLLEGE BY SUSAN MICHELLE DU RAND Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in the Department of History, University of Natal, Durban, 1990. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Page i ABSTRACT Page ii ABBREVIATIONS Page iii INTRODUCTION Page 1 PART I Page 12 "ARISE AND SHINE" The Founders of Adams College The Goals, Beliefs and Strategies of the Missionaries Official Educational Policy Adams College in the 19th Century PART II Pase 49 o^ EDUCATION FOR ASSIMILATION Teaching and Curriculum The Student Body PART III Page 118 TENSIONS. TRANSmON AND CLOSURE The Failure of Mission Education Restructuring African Education The Closure of Adams College CONCLUSION Page 165 APPENDICES Page 170 BIBLIOGRAPHY Page 187 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Paul Maylam for his guidance, advice and dedicated supervision. I would also like to thank Michael Spencer, my co-supervisor, who assisted me with the development of certain ideas and in supplying constructive encouragement. I am also grateful to Iain Edwards and Robert Morrell for their comments and critical reading of this thesis. Special thanks must be given to Chantelle Wyley for her hard work and assistance with my Bibliography. Appreciation is also due to the staff of the University of Natal Library, the Killie Campbell Africana Library, the Natal Archives Depot, the William Cullen Library at the University of the Witwatersrand, the Central Archives Depot in Pretoria, the Borthwick Institute at the University of York and the School of Oriental and African Studies Library at the University of London. -

The Legacy of Inkosi Albert John Luthuli's Christian-Centred Political

Faith and politics in the context of struggle: the legacy of Inkosi Albert John Luthuli’s Christian-centred political leadership Simangaliso Kumalo Ministry, Education & Governance Programme, School of Religion and Theology, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa Abstract Albert John Mvumbi Luthuli, a Zulu Inkosi and former President-General of the African National Congress (ANC) and a lay-preacher in the United Congregational Church of Southern Africa (UCCSA) is a significant figure as he represents the last generation of ANC presidents who were opposed to violence in their execution of the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. He attributed his opposition to violence to his Christian faith and theology. As a result he is remembered as a peace-maker, a reputation that earned him the honour of being the first African to win the Nobel Peace Prize. Also central to Luthuli’s leadership of the ANC and his people at Groutville was democratic values of leadership where the voices of people mattered including those of the youth and women and his teaching on non-violence, much of which is shaped by his Christian faith and theology. This article seeks to examine Luthuli’s legacy as a leader who used peaceful means not only to resist apartheid but also to execute his duties both in the party and the community. The study is a contribution to the struggle of maintaining peace in the political sphere in South Africa which is marked by inter and intra party violence. The aim is to examine Luthuli’s legacy for lessons that can be used in a democratic South Africa. -

List of Outstanding Trc Beneficiaries

List of outstanding tRC benefiCiaRies JustiCe inVites tRC benefiCiaRies to CLaiM tHeiR finanCiaL RePaRations The Department of Justice and Constitutional Development invites individuals, who were declared eligible for reparation during the Truth and Reconciliation Commission(TRC), to claim their once-off payment of R30 000. These payments will be eff ected from the President Fund, which was established in accordance with the Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act and regulations outlined by the President. According to the regulations the payment of the fi nal reparation is limited to persons who appeared before or made statements to the TRC and were declared eligible for reparations. It is important to note that as this process has been concluded, new applications will not be considered. In instance where the listed benefi ciary is deceased, the rightful next-of-kin are invited to apply for payment. In these cases, benefi ciaries should be aware that their relationship would need to be verifi ed to avoid unlawful payments. This call is part of government’s attempt to implement the approved TRC recommendations relating to the reparations of victims, which includes these once-off payments, medical benefi ts and other forms of social assistance, establishment of a task team to investigate the nearly 500 cases of missing persons and the prevention of future gross human rights violations and promotion of a fi rm human rights culture. In order to eff ectively implement these recommendations, the government established a dedicated TRC Unit in the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development which is intended to expedite the identifi cation and payment of suitable benefi ciaries. -

Policy Name Promotion of Access to Information (PAIA) Policy & Procedure Manual Policy Number 1/2/P/2014/1 Status Policy

UGU DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY Policy Name Promotion of Access to Information (PAIA) Policy & Procedure Manual Policy Number 1/2/P/2014/1 Status Policy Date Approved by COUNCIL Date Approved 28 JUNE 2018 Date Last Amended 28 JUNE 2018 Date for Next Review Date Published on Intranet JULY 2018 & Website 1 Contents PREAMBLE .......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 2. DEFINITIONS .................................................................................................................................................................. 3 3. POLICY OBJECTIVES........................................................................................................................................................ 4 3.1 Information and Deputy Information Officer’s details ................................................................................................ 4 3.2 Description of Ugu District Municipality’s Structure .................................................................................................... 4 3.3 Description of Ugu District Municipality’s functions .................................................................................................... 4 3.4 Policy and its availability .......................................................................................................................................... -

African Postal Heritage; African Studies Centre Leiden; APH Paper 15 (Part 2); Ton Dietz South Africa: NATAL: Part 2: Postmarks a -D; Version January 2017

African Postal Heritage; African Studies Centre Leiden; APH Paper 15 (Part 2); Ton Dietz South Africa: NATAL: Part 2: Postmarks A -D; Version January 2017 African Studies Centre Leiden African Postal Heritage APH Paper Nr 15, part 2 Ton Dietz NATAL: POSTMARKS A-D Version January 2017 Introduction Postage stamps and related objects are miniature communication tools, and they tell a story about cultural and political identities and about artistic forms of identity expressions. They are part of the world’s material heritage, and part of history. Ever more of this postal heritage becomes available online, published by stamp collectors’ organizations, auction houses, commercial stamp shops, online catalogues, and individual collectors. Virtually collecting postage stamps and postal history has recently become a possibility. These working papers about Africa are examples of what can be done. But they are work-in-progress! Everyone who would like to contribute, by sending corrections, additions, and new area studies can do so by sending an email message to the APH editor: Ton Dietz ([email protected]). You are welcome! Disclaimer: illustrations and some texts are copied from internet sources that are publicly available. All sources have been mentioned. If there are claims about the copy rights of these sources, please send an email to [email protected], and, if requested, those illustrations will be removed from the next version of the working paper concerned. 96 African Postal Heritage; African Studies Centre Leiden; APH Paper 15 (Part 2); Ton Dietz South Africa: NATAL: Part 2: Postmarks A -D; Version January 2017 African Studies Centre Leiden P.O. -

R603 (Adams) Settlement Plan & Draft Scheme

R603 (ADAMS) SETTLEMENT PLAN & DRAFT SCHEME CONTRACT NO.: 1N-35140 DEVELOPMENT PLANNING ENVIRONMENT AND MANAGEMENT UNIT STRATEGIC SPATIAL PLANNING BRANCH 166 KE MASINGA ROAD DURBAN 4000 2019 FINAL REPORT R603 (ADAMS) SETTLEMENT PLAN AND DRAFT SCHEME TABLE OF CONTENTS 4.1.3. Age Profile ____________________________________________ 37 4.1.4. Education Level ________________________________________ 37 1. INTRODUCTION _______________________________________________ 7 4.1.5. Number of Households __________________________________ 37 4.1.6. Summary of Issues _____________________________________ 38 1.1. BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT ____________________________________ 7 4.2. INSTITUTIONAL AND LAND MANAGEMENT ANALYSIS ___________________ 38 1.2. PURPOSE OF THE PROJECT ______________________________________ 7 4.2.1. Historical Background ___________________________________ 38 1.3. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES ________________________________________ 7 4.2.2. Land Ownership _______________________________________ 39 1.4. MILESTONES/DELIVERABLES ____________________________________ 8 4.2.3. Institutional Arrangement _______________________________ 40 1.5. PROFESSIONAL TEAM _________________________________________ 8 4.2.4. Traditional systems/practices _____________________________ 41 1.6. STUDY AREA _______________________________________________ 9 4.2.5. Summary of issues _____________________________________ 42 1.7. OUTLINE OF THE REPORT ______________________________________ 10 4.3. SPATIAL TRENDS ____________________________________________ 42 2. LEGISLATIVE -

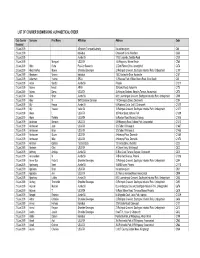

List of Courier Submissions: Alphabetical Order

LIST OF COURIER SUBMISSIONS: ALPHABETICAL ORDER Date Courier Surname First Name Affiliation Address Code Received 21 Jan 2009 eThekwini Transport Authority No address given C84 21 Jan 2009 Individual Chatsworth Circle, Montford C663 21 Jan 2009 Aunde SA 17032 Luganda, Zwelabo Road C730 21 Jan 2009 Manguni USCATA 148 Kingsway, Warner Beach C780 21 Jan 2009 Abbu Ruba Pac-Con Research 22 Dan Pienaar Drive, Amanzimtoti C376 21 Jan 2009 Abdul Gaffoor Moosa Shoreline Beverages 23 Palmgate Crescent, Southgate Industrial Park, Umbogintwini C 397 21 Jan 2009 Abrahams Virsinia Individual 158C Austerville Drive, Austerville C161 21 Jan 2009 Ackerman Yvonne SPCA 10 Riversea Flats, William Brown Road, Illovo Beach C66 21 Jan 2009 Adam Sandra Aunde SA Phoenix C1211 21 Jan 2009 Adams Ismail ARRA 28 Rooks Road, Austerville C170 21 Jan 2009 Adams Berna USCATA 26 Kingsley Gardens, Kingsley Terrace, Amanzimtoti C970 21 Jan 2009 Allan Sham Aunde SA 8-12 Lavendergate Crescent, Southgate Industrial Park, Umbogintwini C599 21 Jan 2009 Alley N SATI Container Services 114 Demograts Street, Chatsworth C294 21 Jan 2009 Ally Feroza Aunde SA 54 Rainbow Circle, Unit 9, Chatsworth C1019 21 Jan 2009 Ally Yaseen Volvo SA 16 Palmgate Crescent, Southgate Industrial Park, Umbogintwini C1277 21 Jan 2009 Alwar L USCATA 38 Prince Street, Athlone Park C1009 21 Jan 2009 Alwar Reshika USCATA 55 Postum Road, Malagazi, Isipingo C1015 21 Jan 2009 Anderson Brennan USCATA 659 Kingsway Road, Athlone Park, Amanzimtoti C1312 21 Jan 2009 Andreasen Joan USCATA 323 Tabor, Winklespruit C1467 -

Journal of Natal and Zulu History, Vol. 28 (2010) 8 – 22

JOURNAL OF NATAL AND ZULU HISTORY, VOL. 28 (2010) The Economic Experimentation of Nembula Duze/Ira Adams Nembula, 1845 – 1886 Eva Jackson University of KwaZulu-Natal Abstract: This paper gives a short biography of Ira Adams Nembula, the Natal sugarcane manufacturer. Nembula's business and his family have been often mentioned but not fully described before in accounts of Natal's nineteenth-century economy and mission stations. This paper draws on historians' narratives and missionary writings on Nembula from the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (American Board), and incorporates information from the archives of the Secretary for Native Affairs (SNA), to look at the life of a man who was described by missionaries as one of the “first fruits” or very first converts to Christianity in Natal, and was a preacher, a pioneering sugarcane producer, and also a transport rider. The paper outlines Nembula's and his mother Mbalasi's position and portrayal as initial converts in the American Board, his sugar milling business, and his plans to farm on a large scale. Nembula's steps towards buying a large tract of land left an impression in the procedures government followed around black land ownership; and may also have contributed to the formulation of colonial laws around black land ownership and exemption from “native law”. Nembula's story in many ways exemplifies the amakholwa experience of what Norman Etherington has called “economic experimentation” and the frustration of that vision. Nembula kaDuze, or Nembula Makhanya, was at one time an important figure in the social and economic world of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (American Board) established in Natal from 1835. -

10. Visual Impact Assessment 10-10

Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for the Proposed Construction, Operation and Decommissioning of a Sea Water Reverse Osmosis FINAL EIA REPORT Plant and Associated Infrastructure Proposed at Lovu on the KwaZulu-Natal South Coast This report presents the visual specialist study prepared by Henry Holland as part of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for the Lovu Sea Water Reverse Osmosis Plant proposed by Umgeni Water in the Lovu area, KwaZulu-Natal. The landscape proposed for the desalination plant sites is predominantly rural-agricultural but it is in close proximity, and surrounded by, an urban landscape with a mixture of landscape character types. West of sites are rural, informal settlements spread out over the rugged terrain of Vulamehlo Municipality, while to the immediate north is the Illovu Village with low- and medium income residential areas as well as a light industrial zone. Further north are residential areas of Kingsburgh and Lovu North. Beyond the N2 in the east are coastal resort towns such as Winklespruit and Illovo Beach. All these landscape types are to some extent visible from the proposed sites. The desalination plant will however introduce a more industrial development type into a landscape that is mostly agricultural in character. A moderate sensitivity to the proposed development is expected for the surrounding landscape character. Key issues and visual receptors The following highly sensitive visual receptors will potentially be affected by the proposed desalination project: . Residents of Mother of Peace Illovo orphanage will potentially be affected by the desalination plant at either site, any of the pipeline routes during construction (particularly the southern route that passes by their property), the pipe bridge and the power line from the desalination plant to the Kingsburgh Major Substation; . -

Province Physical Town Physical Suburb Physical Address Practice Name Contact Number Speciality Practice Number Kwazulu-Natal Am

PROVINCE PHYSICAL TOWN PHYSICAL SUBURB PHYSICAL ADDRESS PRACTICE NAME CONTACT NUMBER SPECIALITY PRACTICE NUMBER KWAZULU-NATAL AMANZIMTOTI AMANZIMTOTI 390 KINGSWAY ROAD JORDAN N 031 903 2335 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 110752 KWAZULU-NATAL AMANZIMTOTI AMANZIMTOTI 388 KINGSWAY ROAD ESTERHUYSEN L 031 903 2351 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 5417341 KWAZULU-NATAL AMANZIMTOTI AMANZIMTOTI 390 KINGSWAY ROAD BOTHA D H 031 903 2335 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 5433169 KWAZULU-NATAL AMANZIMTOTI AMANZIMTOTI 6 IBIS STREET BOS M T 031 903 2188 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 5435838 KWAZULU-NATAL AMANZIMTOTI ATHLONE PARK 392 KINGS ROAD VAN DER MERWE D J 031 903 3120 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 5440068 KWAZULU-NATAL AMANZIMTOTI WINKLESPRUIT 8A MURRAY SMITH ROAD OOSTHUIZEN K M 031 916 6625 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 5451353 KWAZULU-NATAL BERGVILLE TUGELA SQUARE TATHAM ROAD DR DN BLAKE 036 448 1112 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 5430275 KWAZULU-NATAL BLUFF BLUFF 881 BLUFF ROAD Dr SIMONE DHUNRAJ 031 467 8515 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 624292 KWAZULU-NATAL BLUFF FYNNLAND 19 ISLAND VIEW ROAD VALJEE P 031 466 1629 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 5450926 KWAZULU-NATAL CHATSWORTH ARENA PARK 231 ARENA PARK ROAD Dr MAHENDRA ROOPLAL 031 404 8711 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 5449049 KWAZULU-NATAL CHATSWORTH ARENA PARK 249 ARENA PARK ROAD LOKADASEN V 031 404 9095 DENTAL THERAPISTS 9500200 KWAZULU-NATAL CHATSWORTH CHATSWORTH 265 LENNY NAIDU ROAD DR D NAIDOO 031 400 0230 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 116149 KWAZULU-NATAL CHATSWORTH CHATSWORTH 265 LENNY NAIDU ROAD DR K NAIDOO 031 400 0230 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 116149 KWAZULU-NATAL -

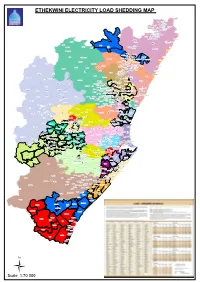

Ethekwini Electricity Load Shedding Map

ETHEKWINI ELECTRICITY LOAD SHEDDING MAP Lauriston Burbreeze Wewe Newtown Sandfield Danroz Maidstone Village Emona SP Fairbreeze Emona Railway Cottage Riverside AH Emona Hambanathi Ziweni Magwaveni Riverside Venrova Gardens Whiteheads Dores Flats Gandhi's Hill Outspan Tongaat CBD Gandhinagar Tongaat Central Trurolands Tongaat Central Belvedere Watsonia Tongova Mews Mithanagar Buffelsdale Chelmsford Heights Tongaat Beach Kwasumubi Inanda Makapane Westbrook Hazelmere Tongaat School Jojweni 16 Ogunjini New Glasgow Ngudlintaba Ngonweni Inanda NU Genazano Iqadi SP 23 New Glasgow La Mercy Airport Desainager Upper Bantwana 5 Redcliffe Canelands Redcliffe AH Redcliff Desainager Matata Umdloti Heights Nellsworth AH Upper Ukumanaza Emona AH 23 Everest Heights Buffelsdraai Riverview Park Windermere AH Mount Moreland 23 La Mercy Redcliffe Gragetown Senzokuhle Mt Vernon Oaklands Verulam Central 5 Brindhaven Riyadh Armstrong Hill AH Umgeni Dawncrest Zwelitsha Cordoba Gardens Lotusville Temple Valley Mabedlane Tea Eastate Mountview Valdin Heights Waterloo village Trenance Park Umdloti Beach Buffelsdraai Southridge Mgangeni Mgangeni Riet River Southridge Mgangeni Parkgate Southridge Circle Waterloo Zwelitsha 16 Ottawa Etafuleni Newsel Beach Trenance Park Palmview Ottawa 3 Amawoti Trenance Manor Mshazi Trenance Park Shastri Park Mabedlane Selection Beach Trenance Manor Amatikwe Hillhead Woodview Conobia Inthuthuko Langalibalele Brookdale Caneside Forest Haven Dimane Mshazi Skhambane 16 Lower Manaza 1 Blackburn Inanda Congo Lenham Stanmore Grove End Westham