ABSTRACT a Director's Approach to Schoolhouse Rock Live

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Every Light in the House Is on Trace Adkins Free Mp3 Download

Every light in the house is on trace adkins free mp3 download CLICK TO DOWNLOAD “Every Light in the House” is a song written by Kent Robbins and recorded by American country music artist Trace Adkins. It was released in August as the second single from his debut. Check out Every Light In The House by Trace Adkins on Amazon Music. Stream ad-free or purchase CD's and MP3s now on renuzap.podarokideal.ru(26). 10/26/ · Every Light In The House Trace Adkins [Intro] F C A# [Verse] F I told you I d leave a light on C In case you ever wanted to come back home A# F C You smiled and said you appreciate the gesture F I took you every word to heart C Cause I can t stand us being apart A# F C And just to show how much I really miss ya [Chorus] F Every light in the house is on C The backyard s bright as the . Trace Adkins Every Light in the House Lyrics More music MP3 download song lyrics: How High the Moon Lyrics, Take Me Back Lyrics, Fools Fall in Love Lyrics, Shooting Star Lyrics, Love Up Lyrics, I'm from the CO Lyrics, Hammer of God Lyrics, Kansas City Lyrics, Few Hours of Light Lyrics, My Devotion Lyrics, Donna the Prima Donna. Download the karaoke of Every Light in the House as made famous by Trace Adkins in the genre Country on Karaoke Version. Every Light in the House Karaoke - Trace Adkins. All MP3 instrumental tracks Instrumentals on demand Latest MP3 instrumental tracks MP3 instrumental tracks Free karaoke files. -

December 1992

VOLUME 16, NUMBER 12 MASTERS OF THE FEATURES FREE UNIVERSE NICKO Avant-garde drummers Ed Blackwell, Rashied Ali, Andrew JEFF PORCARO: McBRAIN Cyrille, and Milford Graves have secured a place in music history A SPECIAL TRIBUTE Iron Maiden's Nicko McBrain may by stretching the accepted role of When so respected and admired be cited as an early influence by drums and rhythm. Yet amongst a player as Jeff Porcaro passes metal drummers all over, but that the chaos, there's always been away prematurely, the doesn't mean he isn't as vital a play- great discipline and thought. music—and our lives—are never er as ever. In this exclusive interview, Learn how these free the same. In this tribute, friends find out how Nicko's drumming masters and admirers share their fond gears move, and what's tore down the walls. memories of Jeff, and up with Maiden's power- • by Bill Milkowski 32 remind us of his deep ful new album and tour. 28 contributions to our • by Teri Saccone art. 22 • by Robyn Flans THE PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY For thirty years the Percussive Arts Society has fostered credibility, exposure, and the exchange of ideas for percus- sionists of every stripe. In this special report, learn where the PAS has been, where it is, and where it's going. • by Rick Mattingly 36 MD TRIVIA CONTEST Win a Sonor Force 1000 drumkit—plus other great Sonor prizes! 68 COVER PHOTO BY MICHAEL BLOOM Education 58 ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC Back To The Dregs BY ROD MORGENSTEIN Equipment Departments 66 BASICS 42 PRODUCT The Teacher Fallacy News BY FRANK MAY CLOSE-UP 4 EDITOR'S New Sabian Products OVERVIEW BY RICK VAN HORN, 8 UPDATE 68 CONCEPTS ADAM BUDOFSKY, AND RICK MATTINGLY Tommy Campbell, Footwork: 6 READERS' Joel Maitoza of 24-7 Spyz, A Balancing Act 45 Yamaha Snare Drums Gary Husband, and the BY ANDREW BY RICK MATTINGLY PLATFORM Moody Blues' Gordon KOLLMORGEN Marshall, plus News 47 Cappella 12 ASK A PRO 90 TEACHERS' Celebrity Sticks BY ADAM BUDOFSKY 146 INDUSTRY FORUM AND WILLIAM F. -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Schoolhouse Rock Live!

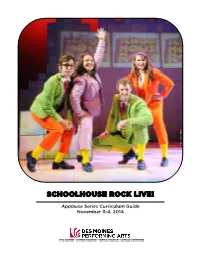

Tim Trumble Photo Photo Trumble Tim SCHOOLHOUSE ROCK LIVE! Applause Series Curriculum Guide November 3-4, 2014 Dear Teachers, Thank you for joining us for the Applause Series presentation of GUIDE CONTENTS Schoolhouse Rock Live! We are thrilled to present this popular Childsplay production for the first time in Des Moines. This high-energy show, packed with catchy, memorable songs, may About Des Moines have you remembering your childhood and watching the original Performing Arts Schoolhouse Rock cartoons that aired on Saturday mornings. Page 3 This time, these songs explode onto the stage for a whole new generation, creating excitement for a variety of academic Going to the Theater and subjects. Theater Etiquette Page 4 We thank you for sharing this very special experience Civic Center Field Trip with your students and Information for Teachers hope this study guide Page 5 helps to connect the performance to your Vocabulary in-classroom Pages 6-7 curriculum in ways that you find valuable. In the About the Performance following pages, you will Pages 8-9 find contextual information about the performance and About Childsplay and the related subjects, as well as a variety of discussion Creative Team questions and assessment activities. Some pages are Page 10 appropriate to reproduce for your students; others are designed more specifically with you, their teacher, in mind. As such, we About Schoolhouse Rock hope that you are able to “pick and choose” material and ideas Page 11 from the study guide to meet your class’s unique needs. Pre-Show -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

Inside Lorton Central Prison: Experiences of Punishment Justified Robert Blecker New York Law School, [email protected]

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Articles & Chapters 1990 Haven or Hell? Inside Lorton Central Prison: Experiences of Punishment Justified Robert Blecker New York Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Law Enforcement and Corrections Commons Recommended Citation Stanford Law Review, Vol. 42, Issue 5 (May 1990), pp. 1149-1250 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. Haven or Hell? Inside Lorton Central Prison: Experiences of Punishment Justified Robert Blecker* I. INTRODUCTION The great challenge of crime and its punishment has produced solu- tions through the ages, ranging from furiously torturing the body of the evil wrongdoer, to compassionately ministering to the soul of the poor wretch. Moved by the gravity of the problem, anguished reformers have given the grand pendulum momentum to swing back and forth over familiar paths, successively claimed as new wisdom but anchored always by a fixed point: the abject failure of the institution of punishment. By 1984, having long since concluded that its own system of punish- ment was not working, Congress had rejected rehabilitation as an out- moded philosophy, abolished parole, and established the United States Sentencing Commission to fix sentences for a vast array of federal crimes, based largely on a philosophy of giving each criminal his just deserts.I On January 18, 1989, rejecting separation-of-powers objec- tions, the United States Supreme Court sustained the Legislature's right to implement its new penal philosophy by delegating power to the Commission. -

Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection

Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection Recordings are on vinyl unless marked otherwise marked (* = Cassette or # = Compact Disc) KEY OC - Original Cast TV - Television Soundtrack OBC - Original Broadway Cast ST - Film Soundtrack OLC - Original London Cast SC - Studio Cast RC - Revival Cast ## 2 (OC) 3 GUYS NAKED FROM THE WAIST DOWN (OC) 4 TO THE BAR 13 DAUGHTERS 20'S AND ALL THAT JAZZ, THE 40 YEARS ON (OC) 42ND STREET (OC) 70, GIRLS, 70 (OC) 81 PROOF 110 IN THE SHADE (OC) 1776 (OC) A A5678 - A MUSICAL FABLE ABSENT-MINDED DRAGON, THE ACE OF CLUBS (SEE NOEL COWARD) ACROSS AMERICA ACT, THE (OC) ADVENTURES OF BARON MUNCHHAUSEN, THE ADVENTURES OF COLORED MAN ADVENTURES OF MARCO POLO (TV) AFTER THE BALL (OLC) AIDA AIN'T MISBEHAVIN' (OC) AIN'T SUPPOSED TO DIE A NATURAL DEATH ALADD/THE DRAGON (BAG-A-TALE) Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection ALADDIN (OLC) ALADDIN (OC Wilson) ALI BABBA & THE FORTY THIEVES ALICE IN WONDERLAND (JANE POWELL) ALICE IN WONDERLAND (ANN STEPHENS) ALIVE AND WELL (EARL ROBINSON) ALLADIN AND HIS WONDERFUL LAMP ALL ABOUT LIFE ALL AMERICAN (OC) ALL FACES WEST (10") THE ALL NIGHT STRUT! ALICE THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS (TV) ALL IN LOVE (OC) ALLEGRO (0C) THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN AMBASSADOR AMERICAN HEROES AN AMERICAN POEM AMERICANS OR LAST TANGO IN HUAHUATENANGO .....................(SF MIME TROUPE) (See FACTWINO) AMY THE ANASTASIA AFFAIRE (CD) AND SO TO BED (SEE VIVIAN ELLIS) AND THE WORLD GOES 'ROUND (CD) AND THEN WE WROTE... (FLANDERS & SWANN) AMERICAN -

Fresh Off the Most Successful Album of His Prolific Career, I'm Comin' Over

Fresh off the most successful album of his prolific career, I’m Comin’ Over, which earned him a #1 debut and numerous industry accolades, Chris Young says he kept getting asked the same question about his hotly anticipated follow up: “Are you feeling the pressure?” But in truth, he wasn’t. Back in the co-producer’s chair with Corey Crowder for the second time (third if you count the 2016 holiday classic, It Must Be Christmas), Young felt completely at ease working on his seventh studio album, Losing Sleep. “I would argue there was less pressure,” says the star, who was just inducted as the newest member of the Grand Ole Opry. “We were even more comfortable than we were last time, and instead of it being like ‘We have to nail this,’ now it was like ‘OK, we did something really cool last time. Let’s try and build on that.’” Young is no stranger to building on success. Over his nearly 12 years with RCA Nashville, he’s steadily taken on more and more responsibility with each project, writing a few more songs each time, staying immersed in his craft and eventually taking the reins completely. With his last project, I’m Comin’ Over, the Tennessee native funneled his wide range of influences into a sound that miXed reverence for country’s past with a sense of eXcitement about its future – and it connected with fans like never before. “I’m Comin’ Over,” “Think of You” (featuring Cassadee Pope), and “Sober Saturday Night” (featuring Vince Gill) all reached the top of the country radio charts, while the first two singles from the project have both earned Platinum-record status. -

Danny Daniels Papers LSC.1925

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8tm7h6q No online items Finding Aid for the Danny Daniels Papers LSC.1925 Finding aid prepared by Douglas Johnson, 2017; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 October 16. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding Aid for the Danny Daniels LSC.1925 1 Papers LSC.1925 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Danny Daniels papers Creator: Daniels, Danny Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1925 Physical Description: 36.2 Linear Feet(61 boxes, 3 cartons, 2 shoe boxes, 16 flat boxes, 2 oversize flat boxes) Date (inclusive): 1925-2004 Date (bulk): 1947-2004 Abstract: Danny Daniels was a tap dancer, choreographer, and entrepreneur. The collection consists primarily of material from his long career on stage and in film and television. There are also records from his eponymous dance school, as well as other business ventures. There is a small amount of personal material, including his collection of theater programs spanning five decades. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: Materials are primarily in English, with a very small portion in French and Italian. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Physical Characteristics and Technical Requirements COLLECTION CONTAINS AUDIOVISUAL MATERIALS: This collection contains both processed and unprocessed audiovisua materials. -

PA Jazz Idol V & the Seventh Annual Jazz Awards

Pennsylvania Jazz Collective presents PA Jazz Idol V & the Seventh Annual Jazz Awards Foy Hall | Moravian College | Bethlehem, Pennsylvania April 18, 2018 Wednesday 7:30pm 1 t Place Spons Firs or Pennsylvania Jazz Collective sincerely thanks Nazareth Music for their support 2 t Place Spons Firs or Pennsylvania Jazz Collective is especially glad to thank all of our sponsors, patrons, and supporters. We know that we cannot do it without you, and we are grateful. Please enjoy this program you made possible. Please join the PA Jazz Collective - your membership and support enables us to present the finest Jazz artists, educate students and develop an audience for America’s music- Jazz online now @ pajazzcollective.org Moravian College encourages persons with disabilities to participate in its programs and activities. If you anticipate needing any type of accommodation or have questions about the physical access provided, please contact Department of Music at [email protected], or call 610-861-1650 at least one week prior to the event. 3 More Events! More Jazz! June 3, 2018: PAJAZZ & Wine Festival Cherry Valley Winery 130 Lower Cherry Valley Rd, Saylorsburg PA 2:00PM-5:00PM 5th Anniversary of Jerry Kozic Memorial Jazz Scholarship Event to honor Bob Dorough-Lifetime Achievement WINNER July 21, 2018: The Third Annual Christmas City Jazz Festival Bethlehem Municipal Ice Rink 345 Illick’s Mill Rd 12:00 – 10:00 pm $15 VIP Seating | $10 General Admission | $5 Students | 17 and under FREE October 14, 2018: Annual “Fall for Jazz” Party 2:00 – 5:00 pm FREE party – Renew membership or become a member Open jam session 52 River St.