A Triangulation of Relationships

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forum on 'Urban Anthropology'

Urbanities, Vol. 3 · No 2 · November 2013 © 2013 Urbanities DISCUSSIONS AND COMMENTS Forum on ‘Urban Anthropology’ Anthropological research in urban settings – often referred to as ‘urban anthropology’, for short – and its attendant ethnographically-based findings are increasingly attracting attention from anthropologists and non-anthropologists alike, including other professionals and decision-makers. In view of its growing importance, this Issue of Urbanities carries a Forum on the topic, which we hope will be of interest to our readers. This Forum opens with the reproduction of an essay by Giuliana B. Prato and Italo Pardo recently published in the UNESCO Encyclopaedia EOLSS, which forms the basis for the discussion that follows in the form of comments and reflections by a number of scholars, in alphabetical order. This special section of Urbanities closes with a brief Report on a round-table Conference on ‘Placing Urban Anthropology: Synchronic and Diachronic Reflections’ held last September at the University of Fribourg and the transcript of the Address given by the Rector of that University during the Conference. 79 Urbanities, Vol. 3 · No 2 · November 2013 © 2013 Urbanities ‘Urban Anthropology’1 Giuliana B. Prato and Italo Pardo (University of Kent, U.K.) [email protected] – [email protected] Established academic disciplinary distinctions led early anthropologists to study tribal societies, or village communities, while ignoring the city as a field of research. Thus, urban research became established in some academic disciplines, particularly sociology, but struggled to achieve such a status in anthropology. Over the years, historical events and geo-political changes have stimulated anthropologists to address processes of urbanization in developing countries; yet, urban research in western industrial societies continued to be left out of the mainstream disciplinary agenda. -

William Wilson Page 1

William Wilson Page 1 William WILSON +Unknown William WILSON b. 1611, d. 1720, Accident In Hayfield At Water Crook +Anne STOUTE Thomas WILSON b. 29 Feb 1664, Kendal, d. 15 Sep 1719, Water Crook +Rachel d. 14 Nov 1704, Kendal William WILSON b. 24 May 1677, d. 1734, bur. 6 Jun 1734 +Sarah BLAYKLING b. 25 Jun 1689, m. 4 May 1710, Brigflatts, d. 27 Jul 1754, par. Thomas BLAYKLING and Mary Thomas WILSON b. 18 Apr 1711, Kendal, bur. 5 Nov 1727, Kendal William WILSON b. 9 Feb 1717, Kendal, bur. 23 Aug 1721, Kendal John WILSON b. 2 Jul 1718, Kendal, bur. 7 Sep 1718, Kendal James WILSON b. 20 Aug 1719, Kendal, d. 3 Dec 1786, Kendal +Lydia BRAITHWAITE b. 28 May 1717, Kendal, m. 2 Mar 1744, Kendal, d. Jul 1769, bur. 30 Jul 1769, Kendal, par. George BRAITHWAITE and Sarah BARNES William WILSON b. 11 Aug 1749, Kendal, d. Sep 1749, Kendal, bur. 6 Sep 1749, Kendal Sarah WILSON b. 14 Jun 1747, Kendal, d. 6 Dec 1818, Scotby, Carlisle +Thomas SUTTON b. 6 May 1741, Scotby, m. 2 Nov 1772, Kendal, d. 10 Jul 1783, Carlisle, par. William SUTTON and Mary Wilson SUTTON b. 4 Feb 1781 Thomnas SUTTON b. 25 Mar 1782 Lydia SUTTON b. 6 Jul 1774 Sarah SUTTON b. 25 Jul 1777, d. 16 Jan 1780 Sarah SUTTON b. 10 Mar 1780, d. 9 Dec 1801 +John IRWIN b. 8 Feb 1742, Moorside, Carlisle, m. 2 Jan 1785, Scotby, Carlisle, d. 24 Feb 1822, Scotby, Carlisle, par. Joseph IRWIN and Sarah Tabitha IRWIN b. -

Letters to Africa

[2OZ] LETTERS TO AFRICA Letters to the Editor should refer to matters raised in the journal and should be signed and give the full address and position of the writer. The Editor reserves the right to shorten letters or to decline them. From Dr. Monica Wilson, Helen Cam Research Fellow,1972: 157) that the Lwembe had not been pre- Girton College, Cambridge eminent as divine king of the Nyakyusa before 1891: Sir, Within recent years three writers, Marcia Wright, "The spiritual authority of the Lwembes which in fart S. R. Charsley, and Michael G. McKenny have dis- probably existed to a limited extent before the 1890s, cussed what they think Nyakyusa society was like is assumed for a much earlier period' (my italics). before the colonial period. Two of them, Marcia She quoted the Berlin missionaries who described Wright and S. R. Charsley, working on mission the challenge to the Lwembe of one claiming to be a correspondence and journals, have provided in- priest of Mbasi in 1893 and concludes: 'it was from valuable material on the interaction between this victory, so it seems, that the wide influence of missions, administration, and Nyakyusa from 1887, Lwembe dated' (Wright, 1972: 158, my italics). In but they have also speculated on what Nyakyusa fact she has no evidence on what existed at Lubaga society was like before the records they use began, before 1891, whereas the accounts given in Communal and the distinction between record and speculation Rituals (1959a) and Divine Kings (M. Wilson, 1959^) is blurred. Moreover, the information given on what came from men who were already holding office as Nyakyusa society was like at the end of last century, priests and chiefs in 1891. -

Clare Univ AR Cover

Annual Report 2011 Clare College Cambridge Contents Master’s Introduction . 3 Teaching and Research . 4–5 Selected Publications by Clare Fellows . 6–7 College Life . 8–9 Financial Report . 10–11 Development . 12–13 Access and Outreach . 14 Captions . 15 2 Master’s Introduction For the second year in a row I am very pleased to report excellent The academic achievements have not been at the expense of a rich College life in music, the arts, and exam results. The College rose from 6 th to 4 th in the Baxter Tables student societies. But I would particularly draw attention to unprecedented sporting success with Blues (17 th in 2009). I received the first inkling of another good run of in rowing, rugby union and hockey as well as a host of other sports. results when I chaired the Part II examiners in History. After Thanks to the support of our alumni, the Development Office, the Investments Committee and our classifying all the students with only the candidates ’ numbers in front Conference Office , the College is well-placed to respond to the financial challenges that are ahead. of the examiners, the Board finally sees a list of the candidates by I should pay particular tribute to Toby Wilkinson’s efforts. Toby has moved to head the University’s name and college. It was only then that I could see that six of the International Strategy Office. Before Toby’s arrival the College raised £400,0 00 in 2002-3 from alumni, Firsts (including one of the starred Firsts ) in History came from Clare, in recent years it has averaged over £2 million a year. -

Anthropology in Northern Rhodesia 1930-1960 Gewald, J.B

Researching and writing in the twilight of an imagined conquest: anthropology in Northern Rhodesia 1930-1960 Gewald, J.B. Citation Gewald, J. B. (2007). Researching and writing in the twilight of an imagined conquest: anthropology in Northern Rhodesia 1930-1960. Asc Working Paper Series, (75). Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12875 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12875 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). African Studies Centre Leiden, The Netherlands Researching and writing in the twilight of an imagined conquest: Anthropology in Northern Rhodesia 1930 - 1960 Jan-Bart Gewald ASC Working Paper 75 / 2007 1 African Studies Centre P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden The Netherlands Telephone +31-71-5273372 Fax +31-71-5273344 E-mail [email protected] Website http://www.ascleiden.nl © Jan-Bart Gewald, 2007 2 Abstract The rich corpus of material produced by the anthropologists of the Rhodes Livingstone Institute (RLI) has come to dominate our understanding of Zambian societies and Zambia's past. The RLI was primarily concerned with the socio-cultural effects of migrant labour. The paper argues that the anthropologists of the RLI worked from within a paradigm that was dominated by the experience of colonial conquest in South Africa. RLI anthropologists transferred their understanding of colonial conquest in South Africa to the Northern Rhodesian situation, without ever truly analysing the manner in which colonial rule had come to be established in Northern Rhodesia. As such the RLI anthropologists operated within a flawed understanding of the past. -

Wilson Booklet.Indd

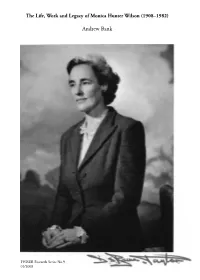

The Life, Work and Legacy of Monica Hunter Wilson (1908–1982) Andrew Bank FHISER Research Series No.9 01/2008 Published by Fort Hare Institute of Social and Economic Research (FHISER) University of Fort Hare 4 Hill Street East London South Africa 5201 Printed in South Africa by Headline Media ISBN 1 86810 029 6 Design and layout: Jenny Sandler Cover design: Headline Media Copyright: Fort Hare Institute of Social and Economic Research All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means; electronic, mechanical, photocopied, recorded or otherwise without prior permission from the publisher. Contents Foreword by Leslie Bank 4 Introduction 6 Childhood: 1 The Hogsback and Alice, 1908–18 8 From History to Anthropology: 2 Girton College, Cambridge, 1927–29 10 A Passion for Fieldwork: 3 Pondoland and the Eastern Cape, 1931–32 14 Reaction to Conquest 1936 16 4 Working with Godfrey among the Nyakyusa: 5 South-western Tanganyika, 1935–38 18 Returning to One’s Roots: 6 Fort Hare, 1944–46 20 Revisiting the Nyakyusa: 7 South-western Tanganyika, 1955 22 African Assistants in the Field: 8 1931-2, 1935-8, 1955 24 Leaving a Legacy: 9 UCT and the Hogsback, 1960–82 26 Endnotes 28 Appendix Monica Hunter Wilson: Awards and Publications 29 4 Foreword The idea of holding a conference to commemorate the life and work of Monica Hunter Wilson was hatched in March 2007 in the rolling hills of Pondoland, where my brother, Andrew Bank, and I had embarked on an exploratory field trip to find Monica Hunter’s original Pondoland field sites. -

Whose Knowledge? the Politics of Scholarship in South(Ern) Africa: A

Book Review Inside African anthropology Page 1 of 4 Whose knowledge? The politics of scholarship BOOK TITLE: in South(ern) Africa: A critical review of Inside Inside African anthropology: Monica Wilson and African Anthropology her interpreters In this review, I raise the critically important issue of scholarly knowledge production among a range of scientific disciplines, particularly those in both the humanities and the sciences that rely on extended periods of fieldwork, through a critical reflection on the book by Andrew and Leslie Bank on the impressive work of the late Professor Monica Wilson. The Bank brothers have put together an important and impressive collection of chapters devoted to two critical issues: in part an initial assessment of Monica Wilson’s work over her entire career, but more critically, a perspective of her interpreters – her field assistants and students, as well as various political interlocutors, friends, colleagues and of course her family, particularly her father. The book traces a chronological, perhaps a genealogical, intellectual development of Monica Wilson, alongside that of her many co-workers, in the production of a series of books, journal publications, presentations of various kinds and talks of hers. It begins with her Cambridge days – where she converted from studying history to anthropology, through to her fieldwork in Pondoland and East London and then her years of fieldwork with her husband Godfrey Wilson in Tanzania, and later to her work in Lovedale, Fort Hare and Rhodes University and finally her move to the University of Cape Town. The key focus of the book is on her co-workers and co-producers of anthropological knowledge. -

History and Theory in Anthropology

History and Theory in Anthropology Anthropology is a discipline very conscious of its history, and Alan Barnard has written a clear, balanced, and judicious textbook that surveys the historical contexts of the great debates in the discipline, tracing the genealogies of theories and schools of thought and con- sidering the problems involved in assessing these theories. The book covers the precursors of anthropology; evolutionism in all its guises; diVusionism and culture area theories, functionalism and structural- functionalism; action-centred theories; processual and Marxist perspec- tives; the many faces of relativism, structuralism and post-structuralism; and recent interpretive and postmodernist viewpoints. alan barnard is Reader in Social Anthropology at the University of Edinburgh. His previous books include Research Practices in the Study of Kinship (with Anthony Good, 1984), Hunters and Herders of Southern Africa (1992), and, edited with Jonathan Spencer, Encyclopedia of Social and Cultural Anthropology (1996). MMMM History and Theory in Anthropology Alan Barnard University of Edinburgh The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org © Alan Barnard 2004 First published in printed format 2000 ISBN 0-511-01616-6 eBook (netLibrary) -

The Objects of Life in Central Africa

The Objects of Life in Central Africa For use by the Author only | © 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV Afrika-Studiecentrum Series Editorial Board Dr Piet Konings (African Studies Centre, Leiden) Dr Paul Mathieu (FAO-SDAA, Rome) Prof. Deborah Posel (University of Cape Town) Prof. Nicolas van de Walle (Cornell University, USA) Dr Ruth Watson (Clare College, Cambridge) VOLUME 30 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/asc For use by the Author only | © 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV The Objects of Life in Central Africa The History of Consumption and Social Change, 1840–1980 Edited by Robert Ross Marja Hinfelaar Iva Peša LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 For use by the Author only | © 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV Cover illustration: Returning to village, Livingstone, Photograph by M.J. Morris, Leya, 1933 (Source: Livingstone Museum). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The objects of life in Central Africa : the history of consumption and social change, 1840-1980 / edited by Robert Ross, Marja Hinfelaar and Iva Pesa. pages cm. -- (Afrika-studiecentrum series ; volume 30) Includes index. ISBN 978-90-04-25490-9 (pbk. : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-25624-8 (e-book) 1. Material culture-- Africa, Central. 2. Economic anthropology--Africa, Central. 3. Africa, Central--Commerce--History. 4. Africa, Central--History I. Ross, Robert, 1949 July 26- II. Hinfelaar, Marja. III. Pesa, Iva. GN652.5.O24 2013 306.3--dc23 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities.