Roots of Modern Arabic Script: from Musnad to Jazm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alif and Hamza Alif) Is One of the Simplest Letters of the Alphabet

’alif and hamza alif) is one of the simplest letters of the alphabet. Its isolated form is simply a vertical’) ﺍ stroke, written from top to bottom. In its final position it is written as the same vertical stroke, but joined at the base to the preceding letter. Because of this connecting line – and this is very important – it is written from bottom to top instead of top to bottom. Practise these to get the feel of the direction of the stroke. The letter 'alif is one of a number of non-connecting letters. This means that it is never connected to the letter that comes after it. Non-connecting letters therefore have no initial or medial forms. They can appear in only two ways: isolated or final, meaning connected to the preceding letter. Reminder about pronunciation The letter 'alif represents the long vowel aa. Usually this vowel sounds like a lengthened version of the a in pat. In some positions, however (we will explain this later), it sounds more like the a in father. One of the most important functions of 'alif is not as an independent sound but as the You can look back at what we said about .(ﺀ) carrier, or a ‘bearer’, of another letter: hamza hamza. Later we will discuss hamza in more detail. Here we will go through one of the most common uses of hamza: its combination with 'alif at the beginning or a word. One of the rules of the Arabic language is that no word can begin with a vowel. Many Arabic words may sound to the beginner as though they start with a vowel, but in fact they begin with a glottal stop: that little catch in the voice that is represented by hamza. -

Arabic Languages (ARAB) 1

Arabic Languages (ARAB) 1 ARAB 2231 (3) Love, Loss and Longing in Classical Arabic Literature ARABIC LANGUAGES (ARAB) Surveys Arabic literature from the sixth through the eighteenth centuries. It offers an introduction to Arabic literature, namely prose and poetry, Courses through its key texts as well as the range of themes and techniques found in this literature, and it lays the groundwork for contextualizing the ARAB 1010 (5) Beginning Arabic 1 literature in the framework of other literary traditions. Taught in English. Introduces students to speaking, listening, reading, and writing skills in Grading Basis: Letter Grade the standard means of communication in the Arab world. This course is Additional Information: Arts Sci Core Curr: Literature and the Arts proficiency-based. All activities within the course are aimed at placing the Arts Sci Gen Ed: Distribution-Arts Humanities student in the context of the native-speaking environment from the very Departmental Category: Arabic Courses in English beginning. Departmental Category: Asia Content Additional Information: Arts Sci Core Curr: Foreign Language Arts Sci Gen Ed: Distribution-Arts Humanities ARAB 2320 (3) The Muslim World, 600-1250 Arts Sci Gen Ed: Foreign Language Focusing on the history of the Muslim World in the age of the caliphates, Departmental Category: Arabic this course takes an interdisciplinary, comparative approach to the Departmental Category: Asia Content development of Islamicate society, focusing on social structure, politics, economics and religion. Students will use primary and secondary sources ARAB 1011 (3) Introduction to Arab and Islamic Civilizations to write a research paper, and make in-class presentations to cultivate Provides an interdisciplinary overview of the cultures of the Arabic- critical thinking, research and writing skills. -

A Study of Kufic Script in Islamic Calligraphy and Its Relevance To

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1999 A study of Kufic script in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century Enis Timuçin Tan University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Tan, Enis Timuçin, A study of Kufic crs ipt in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1999. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/1749 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. A Study ofKufic script in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century. DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by ENiS TIMUgiN TAN, GRAD DIP, MCA FACULTY OF CREATIVE ARTS 1999 CERTIFICATION I certify that this work has not been submitted for a degree to any university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, expect where due reference has been made in the text. Enis Timucin Tan December 1999 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I acknowledge with appreciation Dr. Diana Wood Conroy, who acted not only as my supervisor, but was also a good friend to me. I acknowledge all staff of the Faculty of Creative Arts, specially Olena Cullen, Liz Jeneid and Associate Professor Stephen Ingham for the variety of help they have given to me. -

Language Contact and Identity in Roman Britain

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 5-16-2016 12:00 AM Language Contact and Identity in Roman Britain Robert Jackson Woodcock The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Professor Alexander Meyer The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Classics A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Robert Jackson Woodcock 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Indo- European Linguistics and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Woodcock, Robert Jackson, "Language Contact and Identity in Roman Britain" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3775. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3775 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Language is one of the most significant aspects of cultural identity. This thesis examines the evidence of languages in contact in Roman Britain in order to determine the role that language played in defining the identities of the inhabitants of this Roman province. All forms of documentary evidence from monumental stone epigraphy to ownership marks scratched onto pottery are analyzed for indications of bilingualism and language contact in Roman Britain. The language and subject matter of the Vindolanda writing tablets from a Roman army fort on the northern frontier are analyzed for indications of bilingual interactions between Roman soldiers and their native surroundings, as well as Celtic interference on the Latin that was written and spoken by the Roman army. -

Arabic Language and Literature 1979 - 2018

ARABIC LANGUAGEAND LITERATURE ARABIC LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE 1979 - 2018 ARABIC LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE A Fleeting Glimpse In the name of Allah and praise be unto Him Peace and blessings be upon His Messenger May Allah have mercy on King Faisal He bequeathed a rich humane legacy A great global endeavor An everlasting development enterprise An enlightened guidance He believed that the Ummah advances with knowledge And blossoms by celebrating scholars By appreciating the efforts of achievers In the fields of science and humanities After his passing -May Allah have mercy on his soul- His sons sensed the grand mission They took it upon themselves to embrace the task 6 They established the King Faisal Foundation To serve science and humanity Prince Abdullah Al-Faisal announced The idea of King Faisal Prize They believed in the idea Blessed the move Work started off, serving Islam and Arabic Followed by science and medicine to serve humanity Decades of effort and achievement Getting close to miracles With devotion and dedicated The Prize has been awarded To hundreds of scholars From different parts of the world The Prize has highlighted their works Recognized their achievements Never looking at race or color Nationality or religion This year, here we are Celebrating the Prize›s fortieth anniversary The year of maturity and fulfillment Of an enterprise that has lived on for years Serving humanity, Islam, and Muslims May Allah have mercy on the soul of the leader Al-Faisal The peerless eternal inspirer May Allah save Salman the eminent leader Preserve home of Islam, beacon of guidance. -

The Ogham-Runes and El-Mushajjar

c L ite atu e Vo l x a t n t r n o . o R So . u P R e i t ed m he T a s . 1 1 87 " p r f ro y f r r , , r , THE OGHAM - RUNES AND EL - MUSHAJJAR A D STU Y . BY RICH A R D B URTO N F . , e ad J an uar 22 (R y , PART I . The O ham-Run es g . e n u IN tr ating this first portio of my s bj ect, the - I of i Ogham Runes , have made free use the mater als r John collected by Dr . Cha les Graves , Prof. Rhys , and other students, ending it with my own work in the Orkney Islands . i The Ogham character, the fair wr ting of ' Babel - loth ancient Irish literature , is called the , ’ Bethluis Bethlm snion e or , from its initial lett rs, like “ ” Gree co- oe Al hab e t a an d the Ph nician p , the Arabo “ ” Ab ad fl d H ebrew j . It may brie y be describe as f b ormed y straight or curved strokes , of various lengths , disposed either perpendicularly or obliquely to an angle of the substa nce upon which the letters n . were i cised , punched, or rubbed In monuments supposed to be more modern , the letters were traced , b T - N E E - A HE OGHAM RU S AND L M USH JJ A R . n not on the edge , but upon the face of the recipie t f n l o t sur ace ; the latter was origi al y wo d , s aves and tablets ; then stone, rude or worked ; and , lastly, metal , Th . -

Technical Reference Manual for the Standardization of Geographical Names United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names

ST/ESA/STAT/SER.M/87 Department of Economic and Social Affairs Statistics Division Technical reference manual for the standardization of geographical names United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names United Nations New York, 2007 The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates and analyses a wide range of economic, social and environmental data and information on which Member States of the United Nations draw to review common problems and to take stock of policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member States in many intergovernmental bodies on joint courses of action to address ongoing or emerging global challenges; and (iii) it advises interested Governments on the ways and means of translating policy frameworks developed in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level and, through technical assistance, helps build national capacities. NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of material in the present publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The term “country” as used in the text of this publication also refers, as appropriate, to territories or areas. Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. ST/ESA/STAT/SER.M/87 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. -

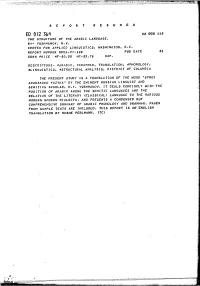

Report Resumes Ed 012 361 the Structure of the Arabic Language

REPORT RESUMES ED 012 361 THE STRUCTURE OF THE ARABIC LANGUAGE. BY- YUSHMANOV; N.V. CENTER FOR APPLIED LINGUISTICS, WASHINGTON,D.C. REPORT NUMBER NDEA-VI-128 PUB DATE EDRS PRICE MF-$0.50 HC-$3.76 94F. DESCRIPTORS- *ARABIC, *GRAMMAR: TRANSLATION,*PHONOLOGY, *LINGUISTICS, *STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS, DISTRICTOF COLUMBIA THE PRESENT STUDY IS A TRANSLATIONOF THE WORK "STROI ARABSK0G0 YAZYKA" BY THE EMINENT RUSSIANLINGUIST AND SEMITICS SCHOLAR, N.Y. YUSHMANOV. IT DEALSCONCISELY WITH THE POSITION OF ARABIC AMONG THE SEMITICLANGUAGES AND THE RELATION OF THE LITERARY (CLASSICAL)LANGUAGE TO THE VARIOUS MODERN SPOKEN DIALECTS, AND PRESENTS ACONDENSED BUT COMPREHENSIVE SUMMARY OF ARABIC PHONOLOGY ANDGRAMMAR. PAGES FROM SAMPLE TEXTS ARE INCLUDED. THIS REPORTIS AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY MOSHE PERLMANN. (IC) w4ur;,e .F:,%ay.47A,. :; -4t N. V. Yushmanov The Structure of the Arabic Language Trar Mated from the Russian by Moshe Perlmann enter for Applied Linguistics of theModern Language Association of America /ashington D.C. 1961 N. V. Yushmanov The Structure of the Arabic Language. Translated from the Russian by Moshe Perlmann Center for Applied Linguistics of the Modern Language Association of America Washington D.C. 1961 It is the policy of the Center for Applied Linguistics to publish translations of linguistic studies and other materials directly related to language problems when such works are relatively inaccessible because of the language in which they are written and are, in the opinion of the Center, of sufficient merit to deserve publication. The publication of such a work by the Center does not necessarily mean that the Center endorses all the opinions presented in it or even the complete correctness of the descriptions of facts included. -

Arabic Alphabet - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Arabic Alphabet from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

2/14/13 Arabic alphabet - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Arabic alphabet From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia َأﺑْ َﺠ ِﺪﯾﱠﺔ َﻋ َﺮﺑِﯿﱠﺔ :The Arabic alphabet (Arabic ’abjadiyyah ‘arabiyyah) or Arabic abjad is Arabic abjad the Arabic script as it is codified for writing the Arabic language. It is written from right to left, in a cursive style, and includes 28 letters. Because letters usually[1] stand for consonants, it is classified as an abjad. Type Abjad Languages Arabic Time 400 to the present period Parent Proto-Sinaitic systems Phoenician Aramaic Syriac Nabataean Arabic abjad Child N'Ko alphabet systems ISO 15924 Arab, 160 Direction Right-to-left Unicode Arabic alias Unicode U+0600 to U+06FF range (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U0600.pdf) U+0750 to U+077F (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U0750.pdf) U+08A0 to U+08FF (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U08A0.pdf) U+FB50 to U+FDFF (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/UFB50.pdf) U+FE70 to U+FEFF (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/UFE70.pdf) U+1EE00 to U+1EEFF (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U1EE00.pdf) Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols. Arabic alphabet ا ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ ع en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arabic_alphabet 1/20 2/14/13 Arabic alphabet - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia غ ف ق ك ل م ن ه و ي History · Transliteration ء Diacritics · Hamza Numerals · Numeration V · T · E (//en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Template:Arabic_alphabet&action=edit) Contents 1 Consonants 1.1 Alphabetical order 1.2 Letter forms 1.2.1 Table of basic letters 1.2.2 Further notes -

The Qur'anic Manuscripts

The Qur'anic Manuscripts Introduction 1. The Qur'anic Script & Palaeography On The Origins Of The Kufic Script 1. Introduction 2. The Origins Of The Kufic Script 3. Martin Lings & Yasin Safadi On The Kufic Script 4. Kufic Qur'anic Manuscripts From First & Second Centuries Of Hijra 5. Kufic Inscriptions From 1st Century Of Hijra 6. Dated Manuscripts & Dating Of The Manuscripts: The Difference 7. Conclusions 8. References & Notes The Dotting Of A Script And The Dating Of An Era: The Strange Neglect Of PERF 558 Radiocarbon (Carbon-14) Dating And The Qur'anic Manuscripts 1. Introduction 2. Principles And Practice 3. Carbon-14 Dating Of Qur'anic Manuscripts 4. Conclusions 5. References & Notes From Alphonse Mingana To Christoph Luxenberg: Arabic Script & The Alleged Syriac Origins Of The Qur'an 1. Introduction 2. Origins Of The Arabic Script 3. Diacritical & Vowel Marks In Arabic From Syriac? 4. The Cover Story 5. Now The Evidence! 6. Syriac In The Early Islamic Centuries 7. Conclusions 8. Acknowledgements 9. References & Notes Dated Texts Containing The Qur’an From 1-100 AH / 622-719 CE 1. Introduction 2. List Of Dated Qur’anic Texts From 1-100 AH / 622-719 CE 3. Codification Of The Qur’an - Early Or Late? 4. Conclusions 5. References 2. Examples Of The Qur'anic Manuscripts THE ‘UTHMANIC MANUSCRIPTS 1. The Tashkent Manuscript 2. The Al-Hussein Mosque Manuscript FIRST CENTURY HIJRA 1. Surah al-‘Imran. Verses number : End Of Verse 45 To 54 And Part Of 55. 2. A Qur'anic Manuscript From 1st Century Hijra: Part Of Surah al-Sajda And Surah al-Ahzab 3. -

In Aswan Arabic

University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 22 Issue 2 Selected Papers from New Ways of Article 17 Analyzing Variation (NWAV 44) 12-2016 Ethnic Variation of */tʕ/ in Aswan Arabic Jason Schroepfer Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl Recommended Citation Schroepfer, Jason (2016) "Ethnic Variation of */tʕ/ in Aswan Arabic," University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: Vol. 22 : Iss. 2 , Article 17. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol22/iss2/17 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol22/iss2/17 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ethnic Variation of */tʕ/ in Aswan Arabic Abstract This study aims to provide some acoustic documentation of two unusual and variable allophones in Aswan Arabic. Although many rural villages in southern Egypt enjoy ample linguistic documentation, many southern urban areas remain understudied. Arabic linguists have investigated religion as a factor influencing linguistic ariationv instead of ethnicity. This study investigates the role of ethnicity in the under-documented urban dialect of Aswan Arabic. The author conducted sociolinguistic interviews in Aswan from 2012 to 2015. He elected to measure VOT as a function of allophone, ethnicity, sex, and age in apparent time. The results reveal significant differences in VOT lead and lag for the two auditorily encoded allophones. The indigenous Nubians prefer a different pronunciation than their Ṣa‘īdī counterparts who trace their lineage to Arab roots. Women and men do not demonstrate distinct pronunciations. Age also does not appear to be affecting pronunciation choice. However, all three variables interact with each other. -

Shahmukhi to Gurmukhi Transliteration System: a Corpus Based Approach

Shahmukhi to Gurmukhi Transliteration System: A Corpus based Approach Tejinder Singh Saini1 and Gurpreet Singh Lehal2 1 Advanced Centre for Technical Development of Punjabi Language, Literature & Culture, Punjabi University, Patiala 147 002, Punjab, India [email protected] http://www.advancedcentrepunjabi.org 2 Department of Computer Science, Punjabi University, Patiala 147 002, Punjab, India [email protected] Abstract. This research paper describes a corpus based transliteration system for Punjabi language. The existence of two scripts for Punjabi language has created a script barrier between the Punjabi literature written in India and in Pakistan. This research project has developed a new system for the first time of its kind for Shahmukhi script of Punjabi language. The proposed system for Shahmukhi to Gurmukhi transliteration has been implemented with various research techniques based on language corpus. The corpus analysis program has been run on both Shahmukhi and Gurmukhi corpora for generating statistical data for different types like character, word and n-gram frequencies. This statistical analysis is used in different phases of transliteration. Potentially, all members of the substantial Punjabi community will benefit vastly from this transliteration system. 1 Introduction One of the great challenges before Information Technology is to overcome language barriers dividing the mankind so that everyone can communicate with everyone else on the planet in real time. South Asia is one of those unique parts of the world where a single language is written in different scripts. This is the case, for example, with Punjabi language spoken by tens of millions of people but written in Indian East Punjab (20 million) in Gurmukhi script (a left to right script based on Devanagari) and in Pakistani West Punjab (80 million), written in Shahmukhi script (a right to left script based on Arabic), and by a growing number of Punjabis (2 million) in the EU and the US in the Roman script.