Marisa Guida

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developing an Intergovernmental Nuclear Regulatory Organization

Developing an Intergovernmental Nuclear Regulatory Organization: Lessons Learned from the International Civil Aviation Organization, the International Maritime Organization, and the International Telecommunication Union Clarence Eugene Carpenter, Jr. Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering, May 1988 Seattle University, Seattle, WA Master of Science in Technical Management, May 1997 The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD Master of Arts in International Science and Technology Policy, May 2009 The George Washington University, Washington, DC A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 10, 2020 Dissertation directed by Kathryn Newcomer Professor of Public Policy and Public Administration The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Clarence Eugene Carpenter, Jr. has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of November 26, 2019. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Developing an Intergovernmental Nuclear Regulatory Organization: Lessons Learned from the International Civil Aviation Organization, the International Maritime Organization, and the International Telecommunication Union Clarence Eugene Carpenter, Jr. Dissertation Research Committee: Kathryn Newcomer, Professor of Public Policy and Public Administration, Dissertation Director Philippe Bardet, Assistant Professor, -

Chapter 4. CLASSIFICATION UNDER the ATOMIC ENERGY

Chapter 4 CLASSIFICATION UNDER THE ATOMIC ENERGY ACT INTRODUCTION The Atomic Energy Act of 1946 was the first and, other than its successor, the Atomic Energy Act of 1954, to date the only U.S. statute to establish a program to restrict the dissemination of information. This Act transferred control of all aspects of atomic (nuclear) energy from the Army, which had managed the government’s World War II Manhattan Project to produce atomic bombs, to a five-member civilian Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). These new types of bombs, of awesome power, had been developed under stringent secrecy and security conditions. Congress, in enacting the 1946 Atomic Energy Act, continued the Manhattan Project’s comprehensive, rigid controls on U.S. information about atomic bombs and other aspects of atomic energy. That Atomic Energy Act designated the atomic energy information to be protected as “Restricted Data” and defined that data. Two types of atomic energy information were defined by the Atomic Energy Act of 1954, Restricted Data (RD) and a type that was subsequently termed Formerly Restricted Data (FRD). Before discussing further the Atomic Energy Act of 1946 and its unique requirements for controlling atomic energy information, some of the special information-control activities that accompanied the research, development, and production efforts that led to the first atomic bomb will be mentioned. Realization that an atomic bomb was possible had a profound impact on the scientists who first became aware of that possibility. The implications of such a weapon were so tremendous that the U.S. scientists conducting the initial, basic research related to nuclear fission voluntarily restricted the publication of their scientific work in this area. -

Grappling with the Bomb: Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

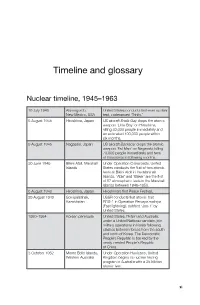

Timeline and glossary Nuclear timeline, 1945–1963 16 July 1945 Alamogordo, United States conducts first-ever nuclear New Mexico, USA test, codenamed ‘Trinity .’ 6 August 1945 Hiroshima, Japan US aircraft Enola Gay drops the atomic weapon ‘Little Boy’ on Hiroshima, killing 80,000 people immediately and an estimated 100,000 people within six months . 9 August 1945 Nagasaki, Japan US aircraft Bockscar drops the atomic weapon ‘Fat Man’ on Nagasaki, killing 70,000 people immediately and tens of thousands in following months . 30 June 1946 Bikini Atoll, Marshall Under Operation Crossroads, United Islands States conducts the first of two atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. ‘Able’ and ‘Baker’ are the first of 67 atmospheric tests in the Marshall Islands between 1946–1958 . 6 August 1948 Hiroshima, Japan Hiroshima’s first Peace Festival. 29 August 1949 Semipalatinsk, USSR conducts first atomic test Kazakhstan RDS-1 in Operation Pervaya molniya (Fast lightning), dubbed ‘Joe-1’ by United States . 1950–1954 Korean peninsula United States, Britain and Australia, under a United Nations mandate, join military operations in Korea following clashes between forces from the south and north of Korea. The Democratic People’s Republic is backed by the newly created People’s Republic of China . 3 October 1952 Monte Bello Islands, Under Operation Hurricane, United Western Australia Kingdom begins its nuclear testing program in Australia with a 25 kiloton atomic test . xi GRAPPLING WITH THE BOMB 1 November 1952 Bikini Atoll, Marshall United States conducts its first Islands hydrogen bomb test, codenamed ‘Mike’ (10 .4 megatons) as part of Operation Ivy . -

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy And

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy and Anglo-American Relations, 1939 – 1958 Submitted by: Geoffrey Charles Mallett Skinner to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, July 2018 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) ……………………………………………………………………………… 1 Abstract There was no special governmental partnership between Britain and America during the Second World War in atomic affairs. A recalibration is required that updates and amends the existing historiography in this respect. The wartime atomic relations of those countries were cooperative at the level of science and resources, but rarely that of the state. As soon as it became apparent that fission weaponry would be the main basis of future military power, America decided to gain exclusive control over the weapon. Britain could not replicate American resources and no assistance was offered to it by its conventional ally. America then created its own, closed, nuclear system and well before the 1946 Atomic Energy Act, the event which is typically seen by historians as the explanation of the fracturing of wartime atomic relations. Immediately after 1945 there was insufficient systemic force to create change in the consistent American policy of atomic monopoly. As fusion bombs introduced a new magnitude of risk, and as the nuclear world expanded and deepened, the systemic pressures grew. -

Trinity Scientific Firsts

TRINITY SCIENTIFIC FIRSTS THE TRINITY TEST was perhaps the greatest scientifi c experiment ever. Seventy-fi ve years ago, Los Alamos scientists and engineers from the U.S., Britain, and Canada changed the world. July 16, 1945 marks the entry into the Atomic Age. PLUTONIUM: THE BETHE-FEYNMAN FORMULA: Scientists confi rmed the newly discovered 239Pu has attractive nuclear Nobel Laureates Hans Bethe and Richard Feynman developed the physics fi ssion properties for an atomic weapon. They were able to discern which equation used to estimate the yield of a fi ssion weapon, building on earlier production path would be most effective based on nuclear chemistry, and work by Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls. The equation elegantly encapsulates separated plutonium from Hanford reactor fuel. essential physics involved in the nuclear explosion process. PRECISION HIGH-EXPLOSIVE IMPLOSION FOUNDATIONAL RADIOCHEMICAL TO CREATE A SUPER-CRITICAL ASSEMBLY: YIELD ANALYSIS: Project Y scientists developed simultaneously-exploding bridgewire detonators Wartime radiochemistry techniques developed and used at Trinity with a pioneering high-explosive lens system to create a symmetrically provide the foundation for subsequent analyses of nuclear detonations, convergent detonation wave to compress the core. both foreign and domestic. ADVANCED IMAGING TECHNIQUES: NEW FRONTIERS IN COMPUTING: Complementary diagnostics were developed to optimize the implosion Human computers and IBM punched-card machines together calculated design, including fl ash x-radiography, the RaLa method, -

The Question of Reducing the Threat Posed by Nations Possessing

Mesaieed International School Model United Nations Forum: General Assembly 1 Issue: The Question of reducing threat posed by nations possessing nuclear Weapons. Student Officer: Subhan Khan Position: Deputy Chair Introduction The issue of nuclear weapons has been an ever-present issue within the world and was the first issue adopted by the UN (United Nations) in 1946. Nuclear armaments when detonated have devastating effects both environmentally and socio-economically via the fallout that it left behind from the bomb exploded. Many nations throughout the world are working to combat the issue, and the dismantling of all these weapons would be the perfect solution to all these issues, but this would be very difficult to do. Over 14,900 reported missiles remain on the Earth, and the decommissioning of all these weapons would be a feat for the human race. There is also the issue that nuclear weapons provide a sense of security and defence to a nation as they can pose a severe threat to any potential adversaries looking to harm a country. The decommissioning of nuclear weapons is an effort to preserve peace in the world and eradicate further complications that are to arise due to the threat of atomic weapons. Nations such as the US (United States) and formally the Soviet Union are unwilling to decommission their nuclear arsenals due to the risk of an attack that may occur at any point with the invention of ICBM’s (Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles). Definition of Key Terms WMD (Weapons of Mass Destruction) Regarded as a chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear weapon that is capable of causing great damage to humans, infrastructure and biological systems in the vicinity of its deployment. -

My Time with Sir Rudolf Peierls

ARTICLE-IN-A-BOX My Time with Sir Rudolf Peierls Professor Peierls took up the Wykeham Professorship at Oxford in October 1963. I started as his research assistant in the Department of Theoretical Physics at the beginning of November the same year. I had just ¯nished my PhD with Mel Preston, a former student of Peierls at Birmingham. Theoretical Physics, which Peierls headed, was a large department housed at 12-14 Parks Road. It had many faculty members, graduate students, post-doctoral fellows, and visiting foreign professors. The faculty included R H Dalitz, the Royal Society professor lured from Chicago, Roger Elliott, D ter Haar, David Brink, L Castillejo, amongst others. In addition to his administrative duties, Peierls lectured on nuclear theory, supervised students, and actively participated in seminars and colloquia. The latter took place at the Clarendon laboratory nearby, where the experimentalists worked. In addition, nuclear physics was also housed at 9 Keble Road. We all took afternoon tea at the Clarendon, thereby bringing some cohesion amongst the diverse groups. At this time, Divakaran and Rajasekaran were both at Oxford ¯nishing their doctoral work with Dalitz. K Chandrakar (plasma physics) and E S Rajagopal (low-temperature physics) were at the Clarendon. As will be clear from Professor Baskaran's article, Peierls was a versatile physicist, having made fundamental contributions in condensed matter physics, statistical mechanics, quantum ¯eld theory and nuclear physics. I think it is fair to say that in the mid-sixties his focus was mostly in nuclear theory, in addition to his work in the Pugwash movement on nuclear disarmament. -

Nonlinear Luttinger Liquid: Exact Result for the Green Function in Terms of the Fourth Painlevé Transcendent

SciPost Phys. 2, 005 (2017) Nonlinear Luttinger liquid: exact result for the Green function in terms of the fourth Painlevé transcendent Tom Price1,2*, Dmitry L. Kovrizhin1,3,4 and Austen Lamacraft1 1 TCM Group, Cavendish Laboratory, University of Cambridge, J.J. Thomson Ave., Cambridge CB3 0HE, UK 2 Institute for Theoretical Physics, Centre for Extreme Matter and Emergent Phenomena, Utrecht University, Princetonplein 5, 3584 CC Utrecht, The Netherlands 3 National Research Centre Kurchatov Institute, 1 Kurchatov Square, Moscow 123182, Russia 4 The Rudolf Peierls Centre for Theoretical Physics, Oxford University, Oxford, OX1 3NP,UK * [email protected] Abstract We show that exact time dependent single particle Green function in the Imambekov– Glazman theory of nonlinear Luttinger liquids can be written, for any value of the Lut- tinger parameter, in terms of a particular solution of the Painlevé IV equation. Our expression for the Green function has a form analogous to the celebrated Tracy–Widom result connecting the Airy kernel with Painlevé II. The asymptotic power law of the exact solution as a function of a single scaling variable x=pt agrees with the mobile impurity results. The full shape of the Green function in the thermodynamic limit is recovered with arbitrary precision via a simple numerical integration of a nonlinear ODE. Copyright T. Price et al. Received 03-01-2017 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Accepted 13-02-2017 Check for Attribution 4.0 International License. Published 21-02-2017 updates Published by the SciPost Foundation. doi:10.21468/SciPostPhys.2.1.005 Contents 1 Introduction2 2 Fredholm determinant3 3 Riemann–Hilbert problem and differential equations4 3.1 Lax equation6 3.2 Painlevé IV6 3.3 Boundary conditions and final result7 3.4 Mobile Impurity Asymptotics8 4 Conclusion 8 A Lax pair 9 B Exact solution to RHP for the Luttinger liquid9 C Numerical solution of differential equations 10 1 SciPost Phys. -

28. Metal - Insulator Transitions

Institute of Solid State Physics Technische Universität Graz 28. Metal - Insulator Transitions Jan. 28, 2018 Metal-insulator transition Atoms far apart: insulator Atoms close together: metal Mott transition (low electron density) There are bound state solutions to the unscreened potential (hydrogen atom) The 1s state of a screened Coulomb potential becomes unbound at ks = 1.19/a0. Bohr radius 1/3 2 43n Mott argued that the transition should be sharp. ks a0 High-temperature oxide superconductors / antiferromagnets Nevill Francis Mott Nobel prize 1977 Mott transition The number of bound states in a finite potential well depends on the width of the well. There is a critical width below which the valence electrons are no longer bound. Semiconductor conductivity at low temperature P in Si degenerate semiconductor Kittel Vanadium sesquioxide V2O3 PM paramagnetic metal PI paramagnetic insulator AFI Antiferromagnetic insulator (2008) 77, 113107 B et al., Phys. Rev. L. Baldassarre, CR crossover regime (poor conductor) Metal-insulator transition Clusters far apart: insulator Clusters close together: metal Charging effects After screening, the next most simple approach to describing electron- electron interactions are charging effects. ee quantum dot The motion of electrons through a single quantum dot is correlated. Q = CV Single electron transistor 2 nA 1 0 mV 0.5 Coulomb blockade Vb Vg -3-2 -1 0 1 2 3 I [pA] 2 nm room temperature SET Pashkin/Tsai NEC Coulomb blockade suppressed by thermal and quantum fluctuations e2 Thermal fluctuations kTB Quantum fluctuations Et 2C 2C Duration of a quantum fluctuation: t ~ e2 RC charging time of the capacitance: RC 2C Charging faster than a quantum fluctuation RC e2 2 R 8 k e2 h 25.5 k Resistance quantum e2 Single electron effects Single-electron effects will be present in any molecular scale circuit Usually considered undesirable and are avoided by keeping the resistance below the resistance quantum. -

Leonard Abdale and Others

IN THE FIRST-TIER TRIBUNAL WPAFCC Refs: as below WAR PENSIONS AND ARMED FORCES COMPENSATION CHAMBER Sitting at Royal Courts of Justice, Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 16th December 2016 TRIBUNALS COURTS AND ENFORCEMENT ACT 2007 TRIBUNAL PROCEDURE (FIRST-TIER TRIBUNAL) (WAR PENSIONS AND ARMED FORCES COMPENSATION CHAMBER) RULES 2008 BEFORE: THE HON MR JUSTICE BLAKE MRS I MCCORD DR J RAYNER BETWEEN 1. LEONARD ABDALE (Deceased) ENT/00203/2015 2. DARRYL BEETON ENT/00202/2015 3. TREVOR BUTLER (Deceased) ENT/00258/2015 4. DEREK HATTON (Deceased) ENT/00200/2015 5. ERNEST HUGHES ENT/00254/2015 6. BRIAN LOVATT ENT/00201/2015 7. DAWN PRITCHARD (Deceased) ENT/00258/2015 8. LAURA SELBY ENT/00199/2015 9. DENIS SHAW (Deceased) ENT/00253/2015 10. JEAN SINFIELD ENT/00204/2015 11. DONALD BATTERSBY (Deceased) ENT/00250/2015 12. ANNA SMITH ENT/00251/2015 Appellants - and - SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE Respondent Hearing Dates: 13 to 30 June 2016 Representation: Roger Ter Haar QC and Richard Sage (instructed pro bono by HOGAN LOVELLS) for Appellants 1 to 10. Christopher Busby, Hugo Charlton and Cecilia Busby acting as pro bono lay representatives for Appellants 11-12. Adam Heppinstall and Abigail Cohen instructed by the Government Legal Department for the Respondent. TRIBUNAL’S DECISION AND REASONS The unanimous DECISION of the Tribunal is: the appeal of each appellant is dismissed save for the appeal of Leonard Abdale deceased in respect of his claim for cataracts. On this issue his appeal is allowed. INDEX TO DETERMINATION PART ONE INTRODUCTION p.5 Outline -

Nuclear Weapons Technology 101 for Policy Wonks Bruce T

NUCLEAR WEAPONS TECHNOLOGY FOR POLICY WONKS NUCLEAR WEAPONS TECHNOLOGY 101 FOR POLICY WONKS BRUCE T. GOODWIN BRUCE T. GOODWIN BRUCE T. Center for Global Security Research Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory August 2021 NUCLEAR WEAPONS TECHNOLOGY 101 FOR POLICY WONKS BRUCE T. GOODWIN Center for Global Security Research Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory August 2021 NUCLEAR WEAPONS TECHNOLOGY 101 FOR POLICY WONKS | 1 This work was performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in part under Contract W-7405-Eng-48 and in part under Contract DE-AC52-07NA27344. The views and opinions of the author expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC. ISBN-978-1-952565-11-3 LCCN-2021907474 LLNL-MI-823628 TID-61681 2 | BRUCE T. GOODWIN Table of Contents About the Author. 2 Introduction . .3 The Revolution in Physics That Led to the Bomb . 4 The Nuclear Arms Race Begins. 6 Fission and Fusion are "Natural" Processes . 7 The Basics of the Operation of Nuclear Explosives. 8 The Atom . .9 Isotopes . .9 Half-life . 10 Fission . 10 Chain Reaction . 11 Critical Mass . 11 Fusion . 14 Types of Nuclear Weapons . 16 Finally, How Nuclear Weapons Work . 19 Fission Explosives . 19 Fusion Explosives . 22 Staged Thermonuclear Explosives: the H-bomb . 23 The Modern, Miniature Hydrogen Bomb . 25 Intrinsically Safe Nuclear Weapons . 32 Underground Testing . 35 The End of Nuclear Testing and the Advent of Science-Based Stockpile Stewardship . 39 Stockpile Stewardship Today . 41 Appendix 1: The Nuclear Weapons Complex . -

Historic Barriers to Anglo-American Nuclear Cooperation

3 HISTORIC BARRIERS TO ANGLO- AMERICAN NUCLEAR COOPERATION ANDREW BROWN Despite being the closest of allies, with shared values and language, at- tempts by the United Kingdom and the United States to reach accords on nuclear matters generated distrust and resentment but no durable arrangements until the Mutual Defense Agreement of 1958. There were times when the perceived national interests of the two countries were unsynchronized or at odds; periods when political leaders did not see eye to eye or made secret agreements that remained just that; and when espionage, propaganda, and public opinion caused addi- tional tensions. STATUS IMBALANCE The Magna Carta of the nuclear age is the two-part Frisch-Peierls mem- orandum. It was produced by two European émigrés, Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls, at Birmingham University in the spring of 1940. Un- like Einstein’s famous letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, with its vague warning that a powerful new bomb might be constructed from uranium, the Frisch-Peierls memorandum set out detailed technical arguments leading to the conclusion that “a moderate amount of U-235 [highly enriched uranium] would indeed constitute an extremely effi- cient explosive.” Like Einstein, Frisch and Peierls were worried that the Germans might already be working toward an atomic bomb against which there would be no defense. By suggesting “a counter-threat with a similar bomb,” they first enunciated the concept of mutual deterrence and recommended “start[ing] production as soon as possible, even if 36 Historic Barriers to Anglo-American Nuclear Cooperation 37 it is not intended to use the bomb as a means of attack.”1 Professor Mark Oliphant from Birmingham convinced the UK authorities that “the whole thing must be taken rather seriously,”2 and a small group of senior scientists came together as the Maud Committee.