ZULFAQAR Journal of Defence Management, Social Science & Humanities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Larian Merdeka Tentera Darat Tahunan - Nasional - Utusan Online

Larian Merdeka Tentera Darat tahunan - Nasional - Utusan Online http://www.utusan.com.my/berita/nasional/larian-merdeka-tentera... CC aa r i aa nn BERITA RENCANA HIBURAN BISNES KOTA PENDIDIKAN S & T GAYA HIDUP SUKAN KL 2017 BERITA › NASIONAL TERKINI UTAMA POLITIK PARLIMEN WILAYAH LUAR NEGARA JENAYAH MAHKAMAH KOMUNITI Larian Merdeka Tentera Darat tahunan HISHAMMUDDIN TUN HUSSEIN menyempurnakan program penyerahan bendera Larian Merdeka Tentera Darat Zon Timur di Kuantan, Pahang, semalam. Turut hadir, Mohamed Affandi Raja Mohamed Noor (kiri) dan Zulkiple Kassim (dua dari kanan). BERNAMA 20 Ogos 2017 3:00 AM KUANTAN 19 Ogos – Tentera Darat akan menjadikan Larian Merdeka yang ketika ini sedang berlangsung melibatkan tiga penjuru iaitu laluan Pantai Timur, Utara dan Selatan, sebagai acara tahunan bagi memeriahkan sambutan Hari Kebangsaan. Panglima Tentera Darat, Jeneral Datuk Seri Zulkiple Kassim berkata, Menteri Pertahanan, Datuk Seri Hishammuddin Tun Hussein yang menyempurnakan larian itu di daerah ini hari ini turut menyatakan hasrat supaya larian itu dijadikan acara tahunan. Kata beliau, larian itu melibatkan jarak keseluruhan 1,413 kilometer yang mana bagi laluan Pantai Timur, acara tersebut bermula pada 12 Mac lalu di Tumpat, Kelantan dan masing-masing Khamis lalu untuk laluan Utara yang bermula di Bukit Kayu Hitam, Kedah serta Selatan yang bermula di Tanjung Piai, Johor. 1 of 5 10/09/2017, 19:16 Larian Merdeka Tentera Darat tahunan - Nasional - Utusan Online http://www.utusan.com.my/berita/nasional/larian-merdeka-tentera... “Larian Merdeka Tentera Darat bertujuan membangkitkan semangat patriotik kepada negara dalam kalangan masyarakat di negara ini. “Kita melihat orang ramai teruja dengan larian ini sekali gus membangkitkan semangat patriotik, perpaduan dan bersatu dalam kalangan mereka untuk menyambut Bulan Kemerdekaan,” katanya dalam sidang akhbar selepas Program Penyerahan Bendera Larian Merdeka Tentera Darat 2017 Zon Timur yang disempurnakan Hishammuddin di Padang Kemunting di sini, hari ini. -

Blue Ocean Strategy

Berita Bukit Aman • Bil. 2-2011 Bil. 2/2011 www.rmp.gov.my ISSN 1394 - 8687 BOS BLUE OCEAN STRATEGY 1 TAHNIAH Berita Bukit Aman • Bil. 2-2011 TUANKU MIZAN ANUGERAH PINGAT KEPADA 256 WARGA PDRM Oleh : Kpl. Noorlidia Mamun uala Lumpur, 19 Mei 2011 – Seri (PSPP). Di antara penerimanya ialah SAC Insp. Rusnah Md. Isa, Sub Insp. Jaafar Paduka Baginda Yang di-Pertuan Datuk Mazlan Mansor, SAC Dato’ Azman Nordin, Sub Insp. Bustami Wahab dan Sub KAgong Al-Wathiqu Billah Tuanku Yusof, SAC Dato’ Yong Lei Choo, ACP Insp. Mohd Isa Simbok. Mizan Zainal Abidin Ibni Al-Marhum Adzman Mohd Jan, ACP Lim Leong Hock, Seterusnya, SM/D Liew Pong Lan, SM Sultan Mahmud Al-Muktafi Billah ACP Rasdi Ramli, ACP Datin Laila Ali, ACP Salim Bah Chi, SM Kumar Mohan, Sjn/D Shah, berkenan menganugerahkan Mohd Azli Abdullah dan ACP Raja Shahrom Ahmad Tamizi Mat Lazim, Sjn. Erip Larong, pingat kepada 256 pegawai dan Raja Abdullah. Sjn. Mohd Turi Mohd She, Sjn. Sharudin anggota Polis Diraja Malaysia Darjah Pahlawan Pasukan Polis (PPP) Mohd Isa dan Sjn. Yok Kasan Yok Keh. (PDRM). Istiadat Penganugerahan pula dianugerahkan kepada 60 pegawai, Diikuti Kpl/D Sidin Marthotikromo, Kpl. Darjah Kepahlawanan Pasukan antaranya Supt. Baharom Abu, Supt. Paul Singaram Karuppiah, L/Kpl. Sorudin Nan, Polis Dan Pingat Keberanian Polis Khiu Khon Chiang, DSP Hajah Noraini Haji L/Kpl. Hun Ak Siong dan L/Kpl. Ahmad itu diadakan sempena Sambutan Othman, DSP Muniandy Ramasamy, ASP Ab. Ghani. Peringatan Hari Polis Ke-204. Istiadat Che Azmi Bidin, ASP Selamat Sainayune, Turut hadir di istiadat yang bersejarah itu berlangsung di Balairong Seri, Istana ASP Turiman Ahmad Tabon, ASP Napri ialah, Inspektor Jeneral Tan Sri Haji Ismail Negara, Kuala Lumpur. -

Malaysia-Racial-Disc

MALAYSIA RACIAL DISCRIMINATION REPORT 2017 Launched on March 21, 2018 in conjunction with the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination Compiled and prepared by: PUSAT KOMAS Malaysia Contact: PUSAT KOMAS A-2-10, 8 Avenue, Jalan Sungai Jernih 8/1, Seksyen 8, 46050, Petaling Jaya, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia. Tel/Fax: +603-79685415 Email: [email protected] Web: www.komas.org TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE Glossary 1 Foreword 2 Executive Summary 4 Definition of Racial Discrimination 5 Racial Discrimination in Malaysia Today 6 Efforts to Promote National Unity in Malaysia in 2017 7 Incidences of Racial Discrimination in Malaysia in 2017 1. Racial and Religious Discrimination 13 2. Racial Discrimination in Other Industries 17 3. Groups, Agencies and Individuals that use Provocative Racial Sentiments 18 4. Political Groups, Hate Speech and Racial Statements 24 5. Entrenched Racism among Malaysians 32 6. Xenophobic Behaviour 33 Special Report: Social Disparity in Sports and the Malaysian Experience 35 Malaysia Federal Constitution 39 Malaysia’s International Human Rights Commitment in Eliminating Racial Discrimination 40 Conclusion and Recommendations 44 GLOSSARY ASWAJA Pertubuhan Ahli Sunnah Wal Jamaah Malaysia (Malaysia Ahli Sunnah Waljamaah Organisation) Bersatu Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia (United Native Party of Malaysia) Bertindak Badan Bertindak Melayu Islam (Malay Islam Action Body) BN Barisan Nasional (National Front) ATM Angkatan Tentera Malaysia (Malaysian Arm Forces) DAP Democratic Action Party Hindraf Hindu -

Academic Calendar 2014/2015 Session

0 ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2014/2015 SESSION Semester I Orientation 1 week 01.09.2014 - 07.09.2014 Lecture 6 week* 08.09.2014 - 17.10.2014 Mid-Semester Break 1 week* 18.10.2014 - 26.10.2014 Lecture 8 week 27.10.2014 - 19.12.2014 Revision Break 1 week * 20.12.2014 - 28.12.2014 Examination 3 week * 29.12.2014 - 16.01.2014 Semester Break 5 week * 17.01.2015 - 22.02.2015 25 week Semester II Lecture 7 week 23.02.2015 - 10.04.2015 Mid-Semester Break 1 week 11.04.2015 - 19.04.2015 Lecture 7 week 20.04.2015 - 05.06.2015 Revision Break 1 week 06.06.2015 - 14.06.2015 Examination 3 week 15.06.2015 - 03.07.2015 19 week Break / Special Semester Break 9 week 04.07.2015 - 06.09.2015 or Lecture & Examination 8 week 04.07.2015 - 28.08.2015 * Malaysian Day (16 September 2014) Hari Raya Aidil Adha (5 October 2014) Deepavali (23 October 2014) Maal Hijrah (25 October 2014) Christmas (25 December 2014) New Year (1 January 2015) Maulidur Rasul (3 January 2015) Thaipusam (3 February 2015) Chinese New Year (19 & 20 February 2015) 1 Opening Message Welcome to all new undergraduates! Congratulations on your successful admission to the faculty. In line with the university’s aspirations to scale the world university rankings, the entry bar for students applying to pursue a degree at the faculty has been raised. Hence, you should regard your admission as an achievement in itself. Aggressive but carefully crafted initiatives since 2009 will only enhance the already glittering record the university had established in producing quality graduates at all levels. -

Top Military Award Conferred on Chief of the Malaysian Armed Forces

Top Military Award Conferred on Chief of the Malaysian Armed Forces 20 Mar 2018 General (GEN) Tan Sri' Raja Mohamed Affandi Bin Raja Mohamed Noor (right) paying compliments after receiving the award from President Halimah Yacob (left) at the Istana. Chief of the Malaysian Armed Forces, General (GEN) Tan Sri' Raja Mohamed Affandi bin Raja Mohamed Noor was conferred Singapore's highest military award, the Darjah Utama Bakti Cemerlang (Tentera) [Distinguished Service Order (Military)], by President Halimah Yacob at the Istana this afternoon. Guests at the investiture included Minister for Defence Dr Ng Eng Hen, Chief of Defence Force Lieutenant-General (LG) Perry Lim, Permanent 1 Secretary for Defence Development Mr Neo Kian Hong, Chief of Army MG Melvyn Ong, as well as other senior government officials and military officers from Singapore and Malaysia. GEN Tan Sri' Affandi was conferred the award for his significant contributions in strengthening the relationship between the Malaysian Armed Forces and the Singapore Armed Forces. Under his leadership, the defence cooperation between the two armed forces has grown from strength to strength. Other than flagship bilateral exercises such as Semangat Bersatu and Malapura, the two armed forces enjoy a wide range of interactions such as high- level visits, officers exchange programmes, and mutual attendance of courses. At the multilateral level, GEN Tan Sri' Affandi has promoted closer military-to-military relations and cooperation between our armed forces under the Five Power Defence Arrangements and the ASEAN Defence Ministers' Meeting. Both armed forces also work together closely in operations such as the Malacca Straits Patrol. These frequent interactions have contributed to regional peace and stability, and strengthened the rapport and camaraderie among the officers and men of both armed forces. -

Ice Skating Short Track Speed Skating

TECHNICAL HANDBOOK FOR ICE SKATING SHORT TRACK SPEED SKATING The information in this Technical Handbook was correct at the time of publication; however, please note that these details may change between this date and the Games. Changes to schedules, procedures, facilities and services, and any other essential information will be communicated to all relevant parties by the organising committee if required. NOCs are advised to check the NOC Relation page (http://www.kualalumpur2017.com.my/noc-relation) for important updates on topics, such as to the competition schedule. Technical Handbook: Ice Skating – Short Track Speed Skating V9: 26.04.2017 1 CONTENTS Page Messages (i) The Honourable Brigadier General Khairy Jamaluddin, Minister of Youth & Sports Malaysia and Chairman of Malaysia SEA Games Kuala Lumpur 2017 Organising Committee (MASOC) ..................................................... 5 (ii) H.R.H. Tunku Tan Sri Imran ibni Almarhum Tuanku Ja’afar, President, South East Asian Games Federation (SEAGF) and Olympic Council of Malaysia .................. 6 (iii) Dato’ Seri Zolkples Embong, Chief Executive Officer, Malaysia SEA Games Kuala Lumpur 2017 Organising Committee (MASOC) ..................................................... 7 1 Competition Information .............................................. 8 1.1 Competition Dates................................................... 8 1.2 Competition Venue ................................................. 8 1.3 Field of Play ........................................................... 8 2 -

Pena Ketua Pengarang

1 PENA KETUA PENGARANG “Selaku penyambung warisan, harus memainkan karakter sebagai pembela nusa dan bangsa dengan terus berjuang, terus bekorban dan terus berusaha mengekalkan apa yang dikecapi kini” lhamdulillah merafak kesyukuran kepada Yang Maha Esa di atas nikmat kesihatan yang baik seraya rezeki yang dilimpah- Akan kepada kita dalam menongkah arus perjalanan kehidupan dalam mencari keredhaanNya. Sebagaimana telah kita sedia maklum, dalam tempoh ini pelbagai hari peristiwa yang mencalit tentang pergorbanan telah kita raikan seperti Hari Raya Aidil Adha, Hari Kemerdekaan, Hari Pahlawan, Hari Penubuhan Malaysia dan tidak dilupakan juga Hari Angkatan Tentera Malaysia. Hatta, bersempena dengan peristiwa-peristiwa tersebut, terpalit diri untuk menyampaikan serta memperingatkan akan semangat perjuangan yang harus terus dipupuk dalam jiwa selaku warganegara juga sebagai anggota badan beruniform. Keamanan dan keharmonian yang dikecapi kini umum diketahui adalah hasil keperihan dan pengorbanan insan-insan terdahulu, selayaknya digelar pejuang, bermati-matian dalam usaha untuk mengembalikan kedaulatan Tanah Melayu pada suatu ketika dahulu. Semangat kepahlawanan serta keberanian jelas terpampang di setiap bait tuturcara, tingkah laku serta pemikiran setiap individu dengan tujuan yang satu iaitu demi mengembalikan senyuman serta gelak tawa pada generasi mendatang. Oleh hal yang sedemikian, pengorbanan pejuang-pejuang ter- dahulu janganlah dipersia begitu sahaja. Usai sudah peranan mer- eka dan kini kita selaku penyambung warisan, harus memainkan karakter sebagai pembela nusa dan bangsa dengan terus berjuang, terus bekorban dan terus berusaha mengekalkan apa yang dikecapi kini. Benar, ada mungkin kita tidak punyai kekentalan seumpama Lt Adnan, tidak punyai keberanian seumpama Kapt Hassan serta tidak segagah pejuang-pejuang lagenda pada masa dahulu. Namun, tidak mustahil untuk kita miliki semua itu sekiranya semangat pengor- banan telah kita pupuk dan pujuk dalam jiwa ini dari masa ke semasa. -

TECHNICAL HANDBOOK for EQUESTRIAN the Information

TECHNICAL HANDBOOK FOR EQUESTRIAN The information in this Technical Handbook was correct at the time of publication; however, please note that these details may change between this date and the Games. Changes to schedules, procedures, facilities and services, and any other essential information will be communicated to all relevant parties by the organising committee if required. NOCs are advised to check the NOC Relation page (http://www.kualalumpur2017.com.my/noc-relation) for important updates on topics, such as to the competition schedule. Technical Handbook: Equestrian VERSION BC-V7C: 05.05.2017 1 CONTENTS Page Messages (i) The Honourable Brigadier General Khairy Jamaluddin, Minister of Youth & Sports Malaysia and Chairman of Malaysia SEA Games Kuala Lumpur 2017 Organising Committee (MASOC) ..................................................... 6 (ii) H.R.H. Tunku Tan Sri Imran ibni Almarhum Tuanku Ja’afar, President, South East Asian Games Federation (SEAGF) and Olympic Council of Malaysia ................. 7 (iii) Dato’ Seri Zolkples Embong, Chief Executive Officer, Malaysia SEA Games Kuala Lumpur 2017 Organising Committee (MASOC)...................................................... 8 1 Competition Information ............................................. 9 1.1 Competition Dates .................................................. 9 1.2 Competition Venues ............................................... 9 2 Events ............................................................................. 9 3 Quotas .......................................................................... -

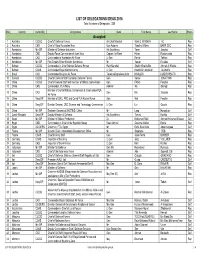

Panglima Setia Mahkota (P.S.M)

TERHAD SENARAI NAMA PENERIMA DARJAH KEBESARAN, BINTANG DAN PINGAT PERSEKUTUAN TAHUN 2014 PANGLIMA SETIA MAHKOTA (P.S.M.) (Membawa Gelaran "Tan Sri") PERKHIDMATAN AWAM 1 YA Dato' Hasan bin Lah Hakim Mahkamah Persekutuan Mahkamah Persekutuan Malaysia Aras 5, Istana Kehakiman, Presint 3 62506 PUTRAJAYA 2 YBhg. Dato' Sri Idrus bin Harun Peguam Cara Negara Pejabat Peguam Cara Negara Jabatan Peguam Negara No. 45, Persiaran Perdana, Presint 4 62100 PUTRAJAYA 3 YBhg. Datuk Dr. Madinah binti Mohamad Ketua Setiausaha Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia Pejabat Ketua Setiausaha Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia Aras 8, Blok E8, Kompleks E Pusat Pentadbiran Kerajaan Persekutuan 62604 PUTRAJAYA 4 YA Dato' Sri Haji Mohamed Apandi bin Haji Ali Hakim Mahkamah Persekutuan Mahkamah Persekutuan Malaysia Aras 5, Istana Kehakiman, Presint 3 62506 PUTRAJAYA 5 YA Dato' Tan Kok Wha Hakim Mahkamah Persekutuan Mahkamah Persekutuan Malaysia Aras 5, Istana Kehakiman, Presint 3 62506 PUTRAJAYA TERHAD TERHAD PERKHIDMATAN AWAM 6 YBhg. Prof. Emeritus Dato' Sri Dr. Zakri bin Abdul Hamid Ahli Lembaga Penasihat Mengenai Sains, Teknologi dan Inovasi kepada Setiausaha Agung dan Ketua-Ketua Eksekutif Agensi-Agensi Pertubuhan Bangsa-bangsa Bersatu (PBB) Pejabat YAB Perdana Menteri Aras 3, Blok Barat, Bangunan Perdana Putra 62502 PUTRAJAYA 7 YA Dato' Sri Zaleha binti Zahari Hakim Mahkamah Persekutuan Mahkamah Persekutuan Malaysia Aras 5, Istana Kehakiman Presint 3 62506 PUTRAJAYA PIHAK BERKUASA TEMPATAN / BADAN BERKANUN 8 YBhg. Datuk Prof. Ir. Dr. Haji Ahmad Zaidee bin Laidin Pengerusi Lembaga Pengarah Universiti Teknikal Malaysia Melaka (UTeM) Hang Tuah Jaya 76100 DURIAN TUNGGAL, MELAKA 9 YBhg. Dato' Paduka Ismee bin Ismail Pengarah Urusan Kumpulan/Ketua Pegawai Eksekutif Lembaga Tabung Haji Lantai 38, Bangunan Tabung Haji No. -

Technical Handbook for Bowling (Tenpin)

TECHNICAL HANDBOOK FOR BOWLING (TENPIN) The information in this Technical Handbook was correct at the time of publication; however, please note that these details may change between this date and the Games. Changes to schedules, procedures, facilities and services, and any other essential information will be communicated to all relevant parties by the organising committee if required. NOCs are advised to check the NOC Relation page (http://www.kualalumpur2017.com.my/noc-relation) for important updates on topics, such as to the competition schedule. Technical Handbook: Bowling (Tenpin) V9: 10.04.2017 1 CONTENTS Page Messages (i) The Honourable Brigadier General Khairy Jamaluddin, Minister of Youth & Sports Malaysia and Chairman of Malaysia SEA Games Kuala Lumpur 2017 Organising Committee (MASOC) ..................................................... 6 (ii) H.R.H. Tunku Tan Sri Imran ibni Almarhum Tuanku Ja’afar, President, South East Asian Games Federation (SEAGF) and Olympic Council of Malaysia .................. 7 (iii) Dato’ Seri Zolkples Embong, Chief Executive Officer, Malaysia SEA Games Kuala Lumpur 2017 Organising Committee (MASOC) ..................................................... 8 1 Competition Information .............................................. 9 1.1 Competition Dates................................................... 9 1.2 Competition Venue ................................................. 9 2 Events .............................................................................. 9 3 Quotas ............................................................................ -

List of All Delegations Updated 12-11-16

LIST OF DELEGATIONS IDEAS 2016 Total Numbers of Delegation : 339 SNo Country Invited By Designation Rank First Name Last Name Status Accepted 1 Australia CJCSC Chief of Defence Forces Air Chief Marshal Mark D. BINSKIN, AC Rep 2 Australia CNS Chief of Royal Australian Navy Vice Admiral Timothy William BARR CSC Rep 3 Azerbaijan Min DP Minister of Defence Industries His Excellency Yaver Jamalov Self 4 Azerbaijan CNS Deputy Force Commander of Azeri Navy Captain 1st Rank Hijran Rustamzada Rep 5 Azerbaijan CAS Commander of Azerbaijan Air Force Lt Gen Ramiz Tahirov Rep 6 Azerbaijan Min DP First Deputy Prime Minister Azerbaijan Mr Yaqub Eyyubov Self 7 Bahrain CJCSC Commander-in-Chief Bahrain Defence Forces Field Marshal Shaikh Khalifa Bin Ahmed Al Khalifa Rep 8 Bahrain COAS Commander Royal Bahraini Army Lt Gen Khalifa Bin Abdullah Al-Khalifa Rep 9 Brazil CAS Commander Brazilian Air Force Tenente-Brigadiero do Ar NIVALDO LUIZ ROSSATO Rep 10 Canada CJCSC Chief of Defence Staff Canadian Defence Forces Gen Vance JONATHAN Rep 11 China CJCSC Chief of General Staff and member of Military Commission Gen FANG Fenghui Rep 12 China CNS Commander, PLA (Navy) Admiral Wu Shengli Rep Member of Central Military Commission & Commander PLA 13 China CAS Gen Ma Xiaotian Rep Air Force 14 China Secy DP Member of CMC, PRC and Comd PLA Rocket Force Gen Wei Fenghe Rep 15 China Secy DP Director General, CMC Science and Technology Commission Lt Gen Liu Gouzhi Rep 16 China Min DP Engineer General of SASTIND, China Mr Long Hongshan Self 17 Czech Republic Secy DP Deputy Minister -

Singapore and Malaysian Armies Conclude Bilateral Military Exercise

Singapore and Malaysian Armies Conclude Bilateral Military Exercise 17 Nov 2015 Chief of Army of the Malaysian Armed Forces (MAF), General Tan Sri Raja Mohamed Affandi bin Raja Mohamed Noor (left), and Chief of Army, Brigadier-General Melvyn Ong (right), co-officiating at the closing ceremony of Exercise Semangat Bersatu. The Chief of Army of the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF), Brigadier-General (BG) Melvyn Ong, and the Chief of Army of the Malaysian Armed Forces, General Tan Sri Raja Mohamed Affandi bin Raja Mohamed Noor, co- officiated at the closing ceremony of Exercise Semangat Bersatu this morning. 1 This year's exercise, conducted in Singapore from 2 to 17 November, is the 21st edition in the series and involved around 575 personnel from both the 3rd Battalion, Singapore Infantry Regiment, and the 10th Royal Malay Regiment. The exercise included professional exchanges and culminated in a combined battalion field exercise. In his closing speech, BG Ong commended the participants for building the "professionalism, friendship and good spirit of the soldiers from both countries", and highlighted that "the mutual understanding among commanders and soldiers will strengthen our bilateral defence relationship". BG Ong added that the SAF is looking forward to the next edition of the exercise in Malaysia next year. First held in 1989, Exercise Semangat Bersatu provides an excellent opportunity for both armies to strengthen their professional interactions and underscores the warm and long-standing defence relations between Singapore and Malaysia. SAF and MAF soldiers interacting over weapons technical handling during the exercise. 2 SAF and MAF soldiers training together during the finale mission of the battalion field training exercise.