JES FAN Selected Press Pavel S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Split at the Root: Prostitution and Feminist Discourses of Law Reform

Split at the Root: Prostitution and Feminist Discourses of Law Reform Margaret A. Baldwin My case is not unique. Violette Leduc' Today, adjustment to what is possible no longer means adjustment, it means making the possible real. Theodor Adorno2 This article originated in some years of feminist activism, and a sustained effort to understand two sentences spoken by Evelina Giobbe, an anti- prostitution activist and educator, at a radical feminist conference in 1987. She said: "Prostitution isn't like anything else. Rather, everything else is like prostitution because it is the model for women's condition."' Since that time, t Assistant Professor of Law, Florida State University College of Law. For my family: Mother Marge, Bob, Tim, John, Scharl, Marilynne, Jim, Robert, and in memory of my father, James. This article was supported by summer research grants from Florida State University College of Law. Otherwise, it is a woman-made product. Thanks to Rhoda Kibler, Mary LaFrance, Sheryl Walter, Annie McCombs, Dorothy Teer, Susan Mooney, Marybeth Carter, Susan Hunter, K.C. Reed, Margy Gast, and Christine Jones for the encouragement, confidence, and love. Evelina Giobbe, Kathleen Barry, K.C. Reed, Susan Hunter, and Toby Summer, whose contributions to work on prostitution have made mine possible, let me know I had something to say. The NCASA Basement Drafting Committee was a turning point. Catharine MacKinnon gave me the first opportunity to get something down on paper; she and Andrea Dworkin let me know the effort counted. Mimi Wilkinson and Stacey Dougan ably assisted in the research and in commenting on drafts. -

Ming-Qing Women's Song Lyrics to the Tune Man Jiang Hong

engendering heroism: ming-qing women’s song 1 ENGENDERING HEROISM: MING-QING WOMEN’S SONG LYRICS TO THE TUNE MAN JIANG HONG* by LI XIAORONG (McGill University) Abstract The heroic lyric had long been a masculine symbolic space linked with the male so- cial world of career and achievement. However, the participation of a critical mass of Ming-Qing women lyricists, whose gendered consciousness played a role in their tex- tual production, complicated the issue. This paper examines how women crossed gen- der boundaries to appropriate masculine poetics, particularly within the dimension of the heroic lyric to the tune Man jiang hong, to voice their reflections on larger historical circumstances as well as women’s gender roles in their society. The song lyric (ci 詞), along with shi 詩 poetry, was one of the dominant genres in which late imperial Chinese women writers were active.1 The two conceptual categories in the aesthetics and poetics of the song lyric—“masculine” (haofang 豪放) and “feminine” (wanyue 婉約)—may have primarily referred to the textual performance of male authors in the tradition. However, the participation of a critical mass of Ming- Qing women lyricists, whose gendered consciousness played a role in * This paper was originally presented in the Annual Meeting of the Association for Asian Studies, New York, March 27-30, 2003. I am deeply grateful to my supervisor Grace S. Fong for her guidance and encouragement in the course of writing this pa- per. I would like to also express my sincere thanks to Professors Robin Yates, Robert Hegel, Daniel Bryant, Beata Grant, and Harriet Zurndorfer and to two anonymous readers for their valuable comments and suggestions that led me to think further on some critical issues in this paper. -

Dear Sister Artist: Activating Feminist Art Letters and Ephemera in the Archive

Article Dear Sister Artist: Activating Feminist Art Letters and Ephemera in the Archive Kathy Carbone ABSTRACT The 1970s Feminist Art movement continues to serve as fertile ground for contemporary feminist inquiry, knowledge sharing, and art practice. The CalArts Feminist Art Program (1971–1975) played an influential role in this movement and today, traces of the Feminist Art Program reside in the CalArts Institute Archives’ Feminist Art Materials Collection. Through a series of short interrelated archives stories, this paper explores some of the ways in which women responded to and engaged the Collection, especially a series of letters, for feminist projects at CalArts and the Women’s Art Library at Goldsmiths, University of London over the period of one year (2017–2018). The paper contemplates the archive as a conduit and locus for current day feminist identifications, meaning- making, exchange, and resistance and argues that activating and sharing—caring for—the archive’s feminist art histories is a crucial thing to be done: it is feminism-in-action that not only keeps this work on the table but it can also give strength and definition to being a feminist and an artist. Carbone, Kathy. “Dear Sister Artist,” in “Radical Empathy in Archival Practice,” eds. Elvia Arroyo- Ramirez, Jasmine Jones, Shannon O’Neill, and Holly Smith. Special issue, Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 3. ISSN: 2572-1364 INTRODUCTION The 1970s Feminist Art movement continues to serve as fertile ground for contemporary feminist inquiry, knowledge sharing, and art practice. The California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) Feminist Art Program, which ran from 1971 through 1975, played an influential role in this movement and today, traces and remains of this pioneering program reside in the CalArts Institute Archives’ Feminist Art Materials Collection (henceforth the “Collection”). -

Remembering the Grandmothers: the International Movement to Commemorate the Survivors of Militarized Sexual Abuse in the Asia-Pacific War

Volume 17 | Issue 4 | Number 1 | Article ID 5248 | Feb 15, 2019 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Remembering the Grandmothers: The International Movement to Commemorate the Survivors of Militarized Sexual Abuse in the Asia-Pacific War Vera Mackie, Sharon Crozier-De Rosa It is over seventy years since the issue of systematized sexual abuse in the Asia-Pacific War came to light in interrogations leading up The Australian War Memorial to the post-Second World War Military Tribunals. There was also widespreadThe Australian War Memorial was established vernacular knowledge of the system in the at the end of the First World War as a ‘shrine, a world-class museum, and an extensive early postwar period in Japan and its former 2 occupied territories. The movement for redress archive’. Its mission is to ‘assist Australians to for the survivors of this system gainedremember, interpret and understand the Australian experience of war and its enduring momentum in East and Southeast Asia in the 3 1970s. By the 1990s this had become a global impact on Australian society’. The holdings include ‘relics, official and private records, art, movement, making connections with other photographs, film, and sound’. The physical international movements and political archive is augmented by an extensive on-line campaigns on the issue of militarized sexual archive of digitized materials.4 From the end of violence. These movements have culminated in the First World War to the present, the advances in international law, where Memorial has been the official repository for militarized sexual violence has been addressed the documentation of Australia’s involvement in in ad hoc Military Tribunals on the former military conflicts and peacekeeping operations. -

Rethinking Feminism Across the Taiwan Strait Author

Out of the Closet of Feminist Orientalism: Rethinking Feminism Across the Taiwan Strait Author: Ya-chen Chen Assistant Professor of Chinese Literature and Asian Studies at the CCNY What is Chinese feminism? What is feminism in the Chinese cultural realm? How does one define, outline, understand, develop, interpret, and represent women and feminism in the Chinese cultural realm? These questions are what scholars will always converse over in the spirit of intellectual dialogue.1 However, the question of “which version of [feminist] history is going to be told to the next generation” in the Chinese cultural realm is what cannot wait for diverse scholars to finish arguing over?2 How to teach younger generations about women and feminism in the Chinese cultural realm and how to define, categorize, summarize, or explain women and feminism in the Chinese cultural realm cannot wait for diverse scholars to articulate an answer that satisfies everyone. How women and feminists in the Chinese cultural realm, especially non- Mainland areas, should identify themselves cannot wait until this debate is over. Because anthologies are generally intended for classroom use, I would like to analyze a number of feminist anthologies to illustrate the unbalanced representation of women and feminism in the Chinese cultural realm. In this conference paper, I will examine the following English-language feminist anthologies: Feminisms: An Anthology of Literary Criticism and 327 Theory; The Second Wave: A Reader in Feminist Theory, Western Feminisms: An Anthology of -

The Affective Turn, Or Getting Under the Skin Nerves: Revisiting Stelarc

Medienimpulse ISSN 2307-3187 Jg. 50, Nr. 2, 2012 Lizenz: CC-BY-NC-ND-3.0-AT The Affective turn, or Getting Under the Skin Nerves: Revisiting Stelarc Jan Jagodzinski Jan Jagodzinski konzentriert sich dabei auf das 0,3-Sekunden- Intervall, das aus neurowissenschaftlicher Sicht zwischen einer Empfindung auf der Haut und deren Wahrnehmung durch das Gehirn verstreicht. Dieses Intervall wird derzeit in der Biokunst durch neue Medientechnologien erkundet. Der bekannte Performance-Künstler Stelarc steht beispielhaft für diese Erkundungen. Am Ende des Beitrags erfolgt eine kurze Reflexion über die Bedeutung dieser Arbeiten für die Medienpädagogik. The 'affective turn' has begun to penetrate all forms of discourses. This essay attempts to theorize affect in terms of the 'intrinsic body,' that is, the unconscious body of proprioceptive operations that occur below the level of medienimpulse, Jg. 50, Nr. 2, 2012 1 Jagodzinski The Affective turn, or Getting Under the Skin Nerves: Revisiting Stelarc cognition. I concentrate on the gap of 0.3 seconds that neuroscience posits as the time taken before sensation is registered through the skin to the brain. which I maintain has become the interval that is currently being explored by bioartists through new media technologies. The well-known performance artist Stelarc is the exemplary case for such an exploration. The essay ends with a brief reflection what this means for media pedagogy. The skin is faster than the word (Massumi 2004: 25). medienimpulse, Jg. 50, Nr. 2, 2012 2 Jagodzinski The Affective turn, or Getting Under the Skin Nerves: Revisiting Stelarc The “affective turn” has been announced,[1] but what exactly is it? Basically, it is an exploration of an “implicit” body. -

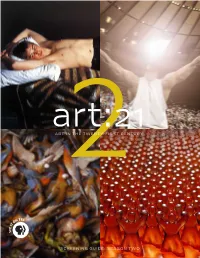

Art in the Twenty-First Century Screening Guide: Season

art:21 ART IN2 THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY SCREENING GUIDE: SEASON TWO SEASON TWO GETTING STARTED ABOUT THIS SCREENING GUIDE ABOUT ART21, INC. This screening guide is designed to help you plan an event Art21, Inc. is a non-profit contemporary art organization serving using Season Two of Art in the Twenty-First Century. This guide students, teachers, and the general public. Art21’s mission is to includes a detailed episode synopsis, artist biographies, discussion increase knowledge of contemporary art, ignite discussion, and inspire questions, group activities, and links to additional resources online. creative thinking by using diverse media to present contemporary artists at work and in their own words. ABOUT ART21 SCREENING EVENTS Public screenings of the Art:21 series engage new audiences and Art21 introduces broad public audiences to a diverse range of deepen their appreciation and understanding of contemporary art contemporary visual artists working in the United States today and and ideas. Organizations and individuals are welcome to host their to the art they are producing now. By making contemporary art more own Art21 events year-round. Some sites plan their programs for accessible, Art21 affords people the opportunity to discover their broad public audiences, while others tailor their events for particular own innate abilities to understand contemporary art and to explore groups such as teachers, museum docents, youth groups, or scholars. possibilities for new viewpoints and self-expression. Art21 strongly encourages partners to incorporate interactive or participatory components into their screenings, such as question- The ongoing goals of Art21 are to enlarge the definitions and and-answer sessions, panel discussions, brown bag lunches, guest comprehension of contemporary art, to offer the public a speakers, or hands-on art-making activities. -

Qiu Jin: an Exemplar of Chinese Feminism, Revolution, and Nationalism at the End of the Qing Dynasty

Qiu Jin: An Exemplar of Chinese Feminism, Revolution, and Nationalism at the End of the Qing Dynasty Jen Kucharski War flames in the north‒when will it all end? I hear the fighting at sea continues unabated. Like the women of Qishi, I worry about my country in vain; It’s hard to trade kerchief and dress for a helmet.1 Qiu Jin is widely hailed as China’s first feminist and is unequivo- cally recognized for her heroic martyrdom at the hands of the Qing dy- nasty in 1907; however, her legacy is far more rich and complicated than being a female revolutionary martyr. In an era in which women had few rights, Qiu Jin chose to doff her kerchief and dress not only to champi- on causes related to women but to fight for her beloved country against tyranny and oppression. Qiu Jin was a well-educated and prolific writer, a self-proclaimed knight-errant, an outspoken critic of the Qing Dynasty and traditional Confucian ideals, a fervent supporter of women’s rights, an outspoken believer in ending the practice of footbinding, a revolutionary martyr, a gifted poet, was skilled in several weapons, and was a skilled 1 Qiu Jin. “War flames in the north‒when will it all end,” in Joan Judge et al. Beyond Exemplar Tales: Women’s Biography in Chinese History (Berkley, California: Global, Area, and International Archive University of California Press, 2011), 1. 94 horseback rider and warrior, trained in several weapons and traditional Chinese martial arts.2 Yet, rarely is she remembered for all of her achieve- ments which diminishes the importance of her rich legacy and demeans the identity she forged for herself. -

Chinese Women in the Early Twentieth Century: Activists and Rebels

Chinese Women in the Early Twentieth Century: Activists and Rebels Remy Lepore Undergraduate Honors Thesis Department of History University of Colorado, Boulder Defended: October 25th, 2019 Committee Members: Primary Advisor: Timothy Weston, Department of History Secondary Reader: Katherine Alexander, Department of Chinese Honors Representative: Miriam Kadia, Department of History Abstract It is said that women hold up half the sky, but what roles do women really play and how do they interact with politics and society? In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries Chinese women reacted in a variety of ways to the social and political changes of the era. Some women were actively engaged in politics while others were not. Some women became revolutionaries and fought for reform in China, other women were more willing to work with and within the established cultural framework. Discussion of reforms and reformers in the late nineteenth-early twentieth centuries are primarily focused on men and male activism; however, some women felt very strongly about reform and were willing to die in order to help China modernize. This thesis explores the life experiences and activism of five women who lived at the end of China’s imperial period and saw the birth of the Republican period. By analyzing and comparing the experiences of Zheng Yuxiu, Yang Buwei, Xie Bingying, Wang Su Chun, and Ning Lao Taitai, this thesis helps to unlock the complex and often hidden lives of Chinese women in modern Chinese history. Lepore 1 Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………..……… 2 Part 1 ………………………………………………………………………………….………… 4 Historiography ……………………………………………………………………………4 Historical Context …………………………..…………………………………………… 8 Part 2: Analysis …………………………………..…………………………..………………. -

Daoist Connections to Contemporary Feminism in China Dessie Miller [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Projects and Capstones Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Spring 5-19-2017 Celebrating the Feminine: Daoist Connections to Contemporary Feminism in China Dessie Miller [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, and the Feminist Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Dessie, "Celebrating the Feminine: Daoist Connections to Contemporary Feminism in China" (2017). Master's Projects and Capstones. 613. https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/613 This Project/Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects and Capstones by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. !1 CELEBRATING THE FEMININE: DAOIST CONNECTIONS TO CONTEMPORARY FEMINISM IN CHINA Dessie D. Miller APS 650: MA Capstone Seminar University of San Francisco 16 May 2017 !2 Acknowledgments I wish to present my special thanks to Professor Mark T. Miller (Associate Professor of Systematic Theology and Associate Director of the St. Ignatius Institute), Professor John K. Nelson (Academic Director and Professor of East Asian religions in the Department of Theology and Religious Studies), Mark Mir (Archivist & Resource Coordinator, Ricci Institute for Chinese-Western Cultural History), Professor David Kim (Associate Professor of Philosophy and Program Director), John Ostermiller (M.A. in Asia Pacific Studies/MAPS Program Peer-Tutor), and my classmates in the MAPS Program at the University of San Francisco for helping me with my research and providing valuable advice. -

Gender, Citizenship and Inequalities Género, Ciudadanía Y Desigualdades

ISSN 1989 - 9572 Gender, citizenship and inequalities Género, ciudadanía y desigualdades Giovanna Campani, University of Florence, Italy Journal for Educators, Teachers and Trainers, Vol. 5 (3) http://www.ugr.es/~jett/index.php Fecha de recepción: 15 de agosto de 2013 Fecha de revisión: 15 de enero de 2014 Fecha de aceptación: 14 de febrero de 2014 Campani, G. (2014). Gender, citizenship and inequalities. Journal for Educators, Teachers and Trainers, Vol. 5(3), pp. 43 – 53. Journal for Educators, Teachers and Trainers JETT, Vol. 5 (3); ISSN: 1989-9572 43 Journal for Educators, Teachers and Trainers, Vol. 5 (3) ISSN 1989 – 9572 http://www.ugr.es/~jett/index.php Gender, citizenship and inequalities Género, ciudadanía y desigualdades Giovanna Campani, University of Florence, Italy [email protected] Resumen La Plataforma de Acción de Beijing y la CEDAW representa un paso importante en la afirmación de los valores comunes y de una opinión compartida sobre la igualdad de género para todas las sociedades humanas, independientemente de sus tradiciones culturales y religiosas. Sin embargo, las fuertes desigualdades de género persisten en prácticamente todo el mundo, como los cuatro parámetros – el trabajo, la educación, la política y la salud, que se utilizan para el Gender Gap indican. El artículo analiza la cuestión de la igualdad de género frente a la persistencia de las desigualdades sociales y económicas, teniendo en cuenta el punto de vista histórico, y enfocando los problemas actuales. El documento plantea una pregunta crucial: ¿es la persistencia -

The Birth of Chinese Feminism Columbia & Ko, Eds

& liu e-yin zHen (1886–1920?) was a theo- ko Hrist who figured centrally in the birth , karl of Chinese feminism. Unlike her contem- , poraries, she was concerned less with China’s eds fate as a nation and more with the relation- . , ship among patriarchy, imperialism, capi- talism, and gender subjugation as global historical problems. This volume, the first translation and study of He-Yin’s work in English, critically reconstructs early twenti- eth-century Chinese feminist thought in a transnational context by juxtaposing He-Yin The Bir Zhen’s writing against works by two better- known male interlocutors of her time. The editors begin with a detailed analysis of He-Yin Zhen’s life and thought. They then present annotated translations of six of her major essays, as well as two foundational “The Birth of Chinese Feminism not only sheds light T on the unique vision of a remarkable turn-of- tracts by her male contemporaries, Jin h of Chinese the century radical thinker but also, in so Tianhe (1874–1947) and Liang Qichao doing, provides a fresh lens through which to (1873–1929), to which He-Yin’s work examine one of the most fascinating and com- responds and with which it engages. Jin, a poet and educator, and Liang, a philosopher e plex junctures in modern Chinese history.” Theory in Transnational ssential Texts Amy— Dooling, author of Women’s Literary and journalist, understood feminism as a Feminism in Twentieth-Century China paternalistic cause that liberals like them- selves should defend. He-Yin presents an “This magnificent volume opens up a past and alternative conception that draws upon anar- conjures a future.