Public Spaces in the Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPCEN Report No. 3.Pdf

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 3 22001155 CCeennssuuss ooff PPooppuullaattiioonn PPooppuullaattiioonn,, LLaanndd AArreeaa,, aanndd PPooppuullaattiioonn DDeennssiittyy Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) conducted the 2015 Census of Population (POPCEN 2015) in August 2015 primarily to update the country’s population and its demographic characteristics, such as the size, composition, and geographic distribution. Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density is among the series of publications that present the results of the POPCEN 2015. This publication provides information on the population size, land area, and population density by region, province, highly urbanized city, and city/municipality based on the data from population census conducted by the PSA in the years 2000, 2010, and 2015; and data on land area by city/municipality as of December 2013 that was provided by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Also presented in this report is the percent change in the population density over the three census years. The population density shows the relationship of the population to the size of land where the population resides. -

Case Study of Metro Manila

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Manasan, Rosario G.; Mercado, Ruben G. Working Paper Governance and Urban Development: Case Study of Metro Manila PIDS Discussion Paper Series, No. 1999-03 Provided in Cooperation with: Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Philippines Suggested Citation: Manasan, Rosario G.; Mercado, Ruben G. (1999) : Governance and Urban Development: Case Study of Metro Manila, PIDS Discussion Paper Series, No. 1999-03, Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Makati City This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/187389 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Philippine Institute for Development Studies Governance and Urban Development: Case Study of Metro Manila Rosario G. -

Priestly Formation in the Asian Contexts

173 ❚Special Issues❚ □ Priestly Formation in the Asian Contexts Priestly Formation in the Asian Contexts: Application of the Church’s Teachings to the Philippine Church and Society* 1 Fr. Rodel E. Aligan, O.P. 〔Pontifical and Royal University of Santo Tomas, Philippines〕 A. The Philippine Situation as a Catholic Nation 1. Evangelization Context 2. Socio-Cultural Context 3. Economic and Political Context 4. The Present Situation of the Catholic Church in the Philippines B. Priestly Formation in the Philippine Context: Application of the Church Teachings to Philippine Church and Society 1. Circumstances of Present-Day Asia 2. Priesthood in the Asian Contexts 3. Priesthood in the Philippine Context 4. The Vision-Mission Statement of the Church in the Philippines 5. Nine Pastoral Priorities of the Church in the Philippines in the Light of PCP II and the National Pastoral Consultation on Church Renewal 6. New Pastoral Priorities of the Church in the Light of the New Evangelization in the Philippines 7. The Implications of the Pastoral Priorities to Priestly Formation in the Philippines 8. The Role of Inculturation on Filipino Priestly Formation *1이 글은 2015년 ‘재단법인 신학과사상’의 연구비 지원을 받아 연구·작성된 논문임. 174 Priestly Formation in the Asian Contexts More than twenty years ago the Philippine Church held the Second Plenary Council of the Philippines on January 20-February 17, 1991, the first being held 38 years ago (1953). It was to take a stock of where the Philippine Church was; to look at where it was going; to reanimate its life in Jesus Christ; and to unite all things in Him.1 During its conclusion after four weeks of discerning it was hoped to be another Pentecost; Christ descending upon the Filipino people, going forth spirited to renew the face of the world ― the Filipinos world first, and through this little world, the wider world of Asia and beyond, giving of ourselves unto the renewal and unity of God’s creation.2 PCP II in the Spirit has looked back in wonder over the Filipinos’ journey as a Christian nation. -

Land Use Planning in Metro Manila and the Urban Fringe: Implications on the Land and Real Estate Market Marife Magno-Ballesteros DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO

Philippine Institute for Development Studies Land Use Planning in Metro Manila and the Urban Fringe: Implications on the Land and Real Estate Market Marife Magno-Ballesteros DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO. 2000-20 The PIDS Discussion Paper Series constitutes studies that are preliminary and subject to further revisions. They are be- ing circulated in a limited number of cop- ies only for purposes of soliciting com- ments and suggestions for further refine- ments. The studies under the Series are unedited and unreviewed. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not neces- sarily reflect those of the Institute. Not for quotation without permission from the author(s) and the Institute. June 2000 For comments, suggestions or further inquiries please contact: The Research Information Staff, Philippine Institute for Development Studies 3rd Floor, NEDA sa Makati Building, 106 Amorsolo Street, Legaspi Village, Makati City, Philippines Tel Nos: 8924059 and 8935705; Fax No: 8939589; E-mail: [email protected] Or visit our website at http://www.pids.gov.ph TABLE of CONTENTS Page 1. Introduction 1 2. The Urban Landscape: Metro Manila and its 2 Peripheral Areas The Physical Environment 2 Pattern of Urban Settlement 4 Pattern of Land Ownership 9 3. The Institutional Environment: Urban Management and Land Use Planning 11 The Historical Precedents 11 Government Efforts Toward Comprehensive 14 Urban Planning The Development Control Process: 17 Centralization vs. Decentralization 4. Institutional Arrangements: 28 Procedural Short-cuts and Relational Contracting Sources of Transaction Costs in the Urban 28 Real Estate Market Grease/Speed Money 33 Procedural Short-cuts 36 5. -

FOI Manuals/Receiving Officers Database

National Government Agencies (NGAs) Name of FOI Receiving Officer and Acronym Agency Office/Unit/Department Address Telephone nos. Email Address FOI Manuals Link Designation G/F DA Bldg. Agriculture and Fisheries 9204080 [email protected] Central Office Information Division (AFID), Elliptical Cheryl C. Suarez (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 2158 [email protected] Road, Diliman, Quezon City [email protected] CAR BPI Complex, Guisad, Baguio City Robert L. Domoguen (074) 422-5795 [email protected] [email protected] (072) 242-1045 888-0341 [email protected] Regional Field Unit I San Fernando City, La Union Gloria C. Parong (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4111 [email protected] (078) 304-0562 [email protected] Regional Field Unit II Tuguegarao City, Cagayan Hector U. Tabbun (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4209 [email protected] [email protected] Berzon Bldg., San Fernando City, (045) 961-1209 961-3472 Regional Field Unit III Felicito B. Espiritu Jr. [email protected] Pampanga (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4309 [email protected] BPI Compound, Visayas Ave., Diliman, (632) 928-6485 [email protected] Regional Field Unit IVA Patria T. Bulanhagui Quezon City (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4429 [email protected] Agricultural Training Institute (ATI) Bldg., (632) 920-2044 Regional Field Unit MIMAROPA Clariza M. San Felipe [email protected] Diliman, Quezon City (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4408 (054) 475-5113 [email protected] Regional Field Unit V San Agustin, Pili, Camarines Sur Emily B. Bordado (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4505 [email protected] (033) 337-9092 [email protected] Regional Field Unit VI Port San Pedro, Iloilo City Juvy S. -

Music in the Heart of Manila: Quiapo from the Colonial Period to Contemporary Times: Tradition, Change, Continuity Ma

Music in The Heart of Manila: Quiapo from the Colonial Period to Contemporary Times: Tradition, Change, Continuity Ma. Patricia Brillantes-Silvestre A brief history of Quiapo Quiapo is a key district of Manila, having as its boundaries the winding Pasig River and the districts of Sta. Cruz, San Miguel and Sampaloc. Its name comes from a floating water lily specie called kiyapo (Pistia stratiotes), with thick, light-green leaves, similar to a tiny, open cabbage. Pre-1800 maps of Manila show Quiapo as originally a cluster of islands with swampy lands and shallow waters (Andrade 2006, 40 in Zialcita), the perfect breeding place for the plant that gave its name to the district. Quiapo’s recorded history began in 1578 with the arrival of the Franciscans who established their main missionary headquarters in nearby Sta. Ana (Andrade 42), taking Quiapo, then a poor fishing village, into its sheepfold. They founded Quiapo Church and declared its parish as that of St. John the Baptist. The Jesuits arrived in 1581, and the discalced Augustinians in 1622 founded a chapel in honor of San Sebastian, at the site where the present Gothic-style basilica now stands. At about this time there were around 30,000 Chinese living in Manila and its surrounding areas, but the number swiftly increased due to the galleon trade, which brought in Mexican currency in exchange for Chinese silk and other products (Wickberg 1965). The Chinese, noted for their business acumen, had begun to settle in the district when Manila’s business center shifted there in the early 1900s (originally from the Parian/Chinese ghetto beside Intramuros in the 1500s, to Binondo in the 1850s, to Sta.Cruz at the turn of the century). -

GML QUARTERLY JANUARY-MARCH 2012 Magazine District 3800 MIDYEAR REVIEW

ROTARY INTERNATIONAL DISTRICT 3800 GML QUARTERLY JANUARY-MARCH 2012 Magazine dISTRICT 3800 MIDYEAR REVIEW A CELEBRATION OF MIDYEAR SUCCESSES VALLE VERDE COUNTRY CLUB JANUARY 21, 2012 3RD QUARTER CONTENTS ROTARY INTERNATIONAL District 3800 The Majestic Governor’s Message 3 Rafael “Raffy” M. Garcia III District Governor District 3800 Midyear Review 4 District Trainer PDG Jaime “James” O. Dee District 3800 Membership Status District Secretary 6 PP Marcelo “Jun” C. Zafra District Governor’s Aide PP Rodolfo “Rudy” L. Retirado District 3800 New Members Senior Deputy Governors 8 PP Bobby Rosadia, PP Nelson Aspe, February 28, 2012 PP Dan Santos, PP Luz Cotoco, PP Willy Caballa, PP Tonipi Parungao, PP Joey Sy Club Administration Report CP Marilou Co, CP Maricris Lim Pineda, 12 CP Manny Reyes, PP Roland Garcia, PP Jerry Lim, PP Jun Angeles, PP Condrad Cuesta, CP Sunday Pineda. District Service Projects Deputy District Secretary 13 Rotary Day and Rotary Week Celebration PP Rudy Mendoza, PP Tommy Cua, PP Danny Concepcion, PP Ching Umali, PP Alex Ang, PP Danny Valeriano, The RI President’s Message PP Augie Soliman, PP Pete Pinion 15 PP John Barredo February 2011 Deputy District Governor PP Roger Santiago, PP Lulu Sotto, PP Peter Quintana, PP Rene Florencio, D’yaryo Bag Project of RCGM PP Boboy Campos, PP Emy Aguirre, 16 PP Benjie Liboro, PP Lito Bermundo, PP Rene Pineda Assistant Governor RY 2011-2012 GSE Inbound Team PP Dulo Chua, PP Ron Quan, PP Saldy 17 Quimpo, PP Mike Cinco, PP Ruben Aniceto, PP Arnold Divina, IPP Benj Ngo, District Awards Criteria PP Arnold Garcia, PP Nep Bulilan, 18 PP Ramir Tiamzon, PP Derek Santos PP Ver Cerafica, PP Edmed Medrano, PP Jun Martinez, PP Edwin Francisco, PP Cito Gesite, PP Tet Requiso, PP El The Majestic Team Breakfast Meeting Bello, PP Elmer Baltazar, PP Lorna 19 Bernardo, PP Joy Valenton, PP Paul January 2011 Castro, Jr., IPP Jun Salatandre, PP Freddie Miranda, PP Jimmy Ortigas, District 3800 PALAROTARY PP Akyat Sy, PP Vic Esparaz, PP Louie Diy, 20 PP Mike Santos, PP Jack Sia RC Pasig Sunrise PP Alfredo “Jun” T. -

LIFE of FOREST STEWARDS (Part 1) August 7, 2021

LIFE OF FOREST STEWARDS (Part 1) August 7, 2021 What is it like to be a Forest Ranger or a Forest Extension Officer? How do you bear patrolling on foot the 10,000 hectares per month target? Or what are the challenges in assisting communities that implements the government’s flagship greening program? There are a lot of interesting facts about being forest stewards. Let us listen to their stories. It’s a hard, tough climb to the second highest peak at 2,117 meters above sea level (masl) in Western Visayas. As majestic as it looks, Mt. Madja-as also holds diverse biological treasures yet to be discovered but more to be protected. Formatted: Font: (Default) Open Sans, 13 pt, Font color: Custom Color(RGB(238,238,238)) Mila Portaje walks inside Bulabog Puti-an National Park. In this beautiful mountain landscape works Margarito Manalo, Jr., one of the Forest Rangers assigned to the Community Environment and Natural Resources Office (CENRO) in Culasi, Antique which covers the jurisdictional upland territories of the municipalities of Culasi, Sebaste, Barbaza, Caluya, Tibiao, Pandan and Libertad. Manalo is one of the team leaders who patrol the forestland areas spanning 64,669.00 hectares. Armed with loving courage and knowledge on forestry laws, Forest Rangers like Margarito would face consequences along their patrol trails that sometimes surprise them and challenge their innovation skills. At one time during their LAWIN patrol, he and his team found abandoned lumbers in the timberland area of Alojipan, Culasi. Regretfully, they could not ask for reinforcement to haul the forest products since it was a dead spot area, and they could neither send a text message nor make a call. -

Landbank of the Philippines Post-Contract Award Disclosure As of March 15, 2021

Landbank of the Philippines Post-Contract Award Disclosure As of March 15, 2021 APPROVED AMOUNT OF NAME OF WINNING OFFICIAL BUSINESS ADDRESS CONTRACT DATE OF DATE OF IMPLEMENTING OFFICE/UNIT OF PROJECT NAME BUDGET FOR THE CONTRACT BIDDER OF THE WINNING BIDDER PERIOD AWARD ACCEPTANCE THE BANK CONTRACT AWARDED TWO (2) YEARS SUBSCRIPTION TO 816,000.00 816,000.00 CONVERGE INFORMATION Reliance Center Annex 1, 99 E. Rodriguez Jr. 10CD/NTP 05-Jan-21 05-Jan-21 NETWORK OPERATIONS DEPARTMENT (NOD) TWO (2) UNITS CONVERGE IBIZ AND COMMUNICATIONS Ave., Ugong, Pasig City (BROADBAND) INTERNET FOR TECHNOLOGY SOLUTIONS, T - 8667-0888 LANDBANK DIOSDADO MACAPAGAL INC. F - 8667-0895 HALL AND ADJACENT ROOMS E - [email protected] MS. PAMELA C. DEL ROSARIO AIRCONDITIONINIG UNITS 555,600.00 522,410.59 MARCO, INC. 12 Matatag Street, Diliman, Quezon City 30CD/NTP AND 05-Jan-21 05-Jan-21 C/O PROJECT MANAGEMENT & ENGINEERING T - 8929-3767 ADVICE FROM DEPARTMENT (PMED) F - 8920-4598 PMED - HIMAMAYLAN BR. E - [email protected] MR. OLIVERT Y. DUYA ONE (1) YEAR HARDWARE 47,000,000.00 47,000,000.00 IBM PHILIPPINES, INC. 28/F One World Place, 32nd Street, ONE (1) YEAR 05-Jan-21 05-Jan-21 DATA CENTER MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT MAINTENANCE SERVICES FOR IBM Bonifacio Global City, Taguig City BEGINNING ON (DCMD) MACHINES T - 8995-2426 THE RECEIPT OF CP - 0917-6344723 NTP E - [email protected] MR. RAMIL D. CABODIL VARIOUS VAULTS AND SAFES 627,710.00 341,500.00 MOSLER PHILIPPINES, INC. 8011 Elisco Road, Ibayo, Tipas, Taguiig City 30CD/NTP AND 06-Jan-21 06-Jan-21 C/O PROJECT MANAGEMENT & ENGINEERING T - 8641-4054 ADVICE FROM DEPARTMENT (PMED) E - [email protected] PMED - BALINGASAG BRANCH MR. -

The Ateneo De Manila University Sustainability Report for School Year 2012 - 2014 Contents GRI Report Profile

ATENEO DE MANILA UNIVERSITY SUSTAINABILITY REPORT JULY 2014 The Ateneo de Manila University Sustainability Report for School Year 2012 - 2014 Contents GRI Report Profile Strategic Thrust of Ateneo de Manila University 2011-2016 Reporting Period April 2012 – March 2014 Statement from the President Introduction to the Report Date of Most Recent Previous Report - Reporting Cycle Biennial The Ateneo de Manila University 10 Contact Point Ma. Assunta C. Cuyegkeng, Ph.D. History Population Director Vision and Mision Entities Ateneo Institute of Sustainability Ethics and Integrity Centers and Units [email protected] The Ateneo Community Stakeholder Engagement The Campuses Surveys In Accordance Option Core, not externally assured International Linkages University Activities and University Linkages Operations Stakeholders What Matters to Us The Ateneo Sustainability Report 2014 was prepared in accordance with the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) G4 Guidelines. Economic Impacts 27 Economic Performance Indirect Economic Impacts Credits Environmental Impact Writers Contributors Layout Artist 33 Energy Effluents and Waste Assunta Cuyegkeng Jon Bilog Earl Juanico Aaron Corpuz Biodiversity Materials Abigail Favis Enrico Bunyi Carlie Labaria Social Impact Kendra Gotangco Katrina Cabanos Anna Mendiola 43 Marion Tan Trinket Canlas-Constantino Roi Victor Pascua Employment Local Communities Labor/Management Relations Rachel Consunji Carissa Quintana Andreas Dorner Jervy Robles Index 53 Zachery Feinberg Chuck Tibayan Sustainability Policies About the Ateneo Institue of Hendrick Freitag Aaron Vicencio Acknowledgements Sustainability Additional Photo Credits: Reuben L. Justo, http://reubenjusto.tripod.com (Old Manila Observatory) Manila Observatory Website, http://www.observatory.ph (Father Federico Faura, SJ) Aegis 2014 The heart of sustainability lives ‘‘ in the people, who choose to be ‘‘ responsible for themselves and the greater society, for the present and the future. -

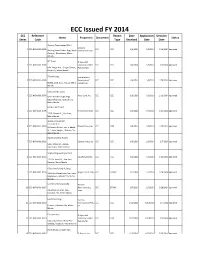

ECC Issued FY 2014 ECC Reference Report Date Application Decision Name Proponent Document Status Series Code Type Received Date Date

ECC Issued FY 2014 ECC Reference Report Date Application Decision Name Proponent Document Status Series Code Type Received Date Date Alabang Town Center BPO 1 Alabang 1 ECC-NCR-1401-0001 ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/16/2014 Approved Alabang Town Center, Brgy. Ayala, Commercial Corp. Alabang,, Muntinlupa, Metro Manila IBP Tower Ortigas and 2 ECC-NCR-1401-0003 Company Limited ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 2/6/2014 Approved Julia Vargas Ave., Ortigas Center,, Partnershipp Pasig City, Metro Manila T-Park Project Fort Bonifacio 3 ECC-NCR-1401-0005 Development ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/28/2014 Approved B18,L4, 26th, BGC,, Taguig, Metro Corporation Manila Vertis North Towers 4 ECC-NCR-1401-0006 Ayala Land, Inc. ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/16/2014 Approved Vertis North Triangle, Brgy. Bagong Pag-asa,, Quezon City, Metro Manila Fortune Hill Project 5 ECC-NCR-1401-0008 Filinvest Land, Inc. ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/20/2014 Approved 173 P. Gomez St.,, San Juan, Metro Manila Studio A Residential Condominium 6 ECC-NCR-1401-0009 Filinvest Land, Inc. ECC IEER 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/20/2014 Approved 99 Xavierville Ave., cor. E. Abada St., Loyola Heights,, Quezon City, Metro Manila Plastic Recycling Project 7 ECC-NCR-1401-0011 Sanplas Industries ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 2/7/2014 Approved 6390 Tatalon St., Ugong,, Valenzuela, Metro Manila Shipbuilding and Repair Yard 8 ECC-NCR-1401-0013 Sas Shipyard, Inc. -

20 October 2010 Philippine Stock Exchange Disclosures Department 3/F, Tower One and Exchange Plaza Ayala Triangle, Ayala Avenue

20 October 2010 Philippine Stock Exchange Disclosures Department 3/F, Tower One and Exchange Plaza Ayala Triangle, Ayala Avenue Makati City Attention : Ms. Janet Encarnacion Head – Disclosures Department Re : ROXAS AND COMPANY, INC. (Formerly CADP GROUP CORPORATION) ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ Gentlemen: We respectfully submit the Annual List of Stockholders of Roxas and Company, Inc. (formerly CADP Group Corporation and herein referred to as the “Company”) as of Record Date, 15 October 2010, prepared by Unionbank Stock Transfer Unit, the Company’s stock transfer agent. Very truly yours, FRITZIE P. TANGKIA‐FABRICANTE Asst. Corporate Secretary/Compliance Officer 7th Floor Cacho Gonzales Building 101 Aguirre Street, Legaspi Village 1229 Makati City Tel No.: (02) 810‐8901 www.roxascompany.com.ph ROXAS AND COMPANY, INC. List of Stockholders as of Record Date 15 October 2010 SN STOCKHOLDERS NAME ADDRESS SHARES 10082856 A. SORIANO CORPORATION SORIANO BUILDING, MAKATI CITY 2,710 10082014 ABAD AURORA C/O BANK OF ASIA, DASMARINAS MANILA 40 10071504 ABAQUIN GIL 3666-C GEN. A. LUNA ST. BANOKAL, MAKATI, MM 402 10071514 ABAQUIN LOURDES M. #6 RIZAL ST., AYALA HEIGHTS QUEZON CITY 742 10079516 ABAT NESTOR A. PASIG BOULEVARD,BARRIO PINEDA PASIG CITY 538 10082024 ABAYA AMELIA R. 153 LT., ARTIAGA, SAN JUAN, MM 3,340 10082034 ABAYA MELCHOR R. 153 LT., ARTIAGA, SAN JUAN, MM 1,560 10082044 ABAYA VICENTE R. 153 LT., ARTIAGA, SAN JUAN, MM 3,340 C/O CADP CG BUILDING, 101 AGUIRRE STREET 10079637 ABELEDA ANASTACIO 18 LEGASPI VILLAGE, MAKATI CITY C/O CADP CG BUILDING, 101 AGUIRRE STREET 10079647 ABELLERA ERNESTO 179 LEGASPI VILLAGE, MAKATI CITY C/O CADP CG BUILDING, 101 AGUIRRE STREET 10079657 ABELLERA SUSAN C.