The Scientist : Physics Meets the Brain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Boltzmann Machine Implementation for the D-Wave

A Boltzmann Machine Implementation for the D-Wave John E. Dorband Ph.D. Dept. of Computer Science and Electrical Engineering University of Maryland, Baltimore County Baltimore, Maryland 21250, USA [email protected] Abstract—The D-Wave is an adiabatic quantum computer. It is an understatement to say that it is not a traditional computer. It can be viewed as a computational accelerator or more precisely a computational oracle, where one asks it a relevant question and it returns a useful answer. The question is how do you ask a relevant question and how do you use the answer it returns. This paper addresses these issues in a way that is pertinent to machine learning. A Boltzmann machine is implemented with the D-Wave since the D-Wave is merely a hardware instantiation of a partially connected Boltzmann machine. This paper presents a prototype implementation of a 3-layered neural network where the D-Wave is used as the middle (hidden) layer of the neural network. This paper also explains how the D-Wave can be utilized in a multi-layer neural network (more than 3 layers) and one in which each layer may be multiple times the size of the D- Wave being used. Keywords-component; quantum computing; D-Wave; neural network; Boltzmann machine; chimera graph; MNIST; I. INTRODUCTION The D-Wave is an adiabatic quantum computer [1][2]. Its Figure 1. Nine cells of a chimera graph. Each cell contains 8 qubits. function is to determine a set of ones and zeros (qubits) that minimize the objective function, equation (1). -

Spring 2013 Mapping (CBAM)

UBATOR http://inc.uscd.edu/ In this Issue: UCSD Creates Center for Brain Activity Mapping On the Cover UCSD Creates Responding to President Barack Obama’s “grand challenge” to chart Center for Brain the function of the human brain in unprecedented detail, the University Activity Mapping of California, San Diego has established the Center for Brain Activity Spring 2013 Mapping (CBAM). The new center, under the aegis of the interdisciplinary Kavli Institute for Brain and Sejnowski Elected to Mind, will tackle the technological and biological challenge of developing a new American Academy generation of tools to enable recording of neuronal activity throughout the brain. It of Arts and Sciences will also conduct brain-mapping experiments and analyze the collected data. Pg 3 Ralph Greenspan–one of the original architects of a visionary proposal that eventually led to the national BRAIN Initiative launched by President Obama in April–has been named CBAM’s founding director. (cont on page 2) Faculty Spotlight: Garrison W. Cottrell Pg 4 Faculty Spotlight: Patricia Gorospe Pg 7 INC Events Pg 9 INC at a glance Pg 10 From left, Nick Spitzer, Ralph Greenspan, and Terry Sejnowski. (Photos by Erik Jepsen/UC San Diego Publications) 1 INSTITUTE FOR NEURAL COMPUTATION Brain Activity Mapping, cont from page 1 UC San Diego Chancellor Pradeep K. Khosla, who attended Obama’s unveiling of the BRAIN Initiative, said: “I am pleased to announce the launch of the Spring 2013 Center for Brain Activity Mapping. This new center will require the type of in-depth and impactful research that we are so good at producing at UC San Diego. -

SFR27 13 Harris Et Al.Indd

From “The Neocortex,” edited by W. Singer, T. J. Sejnowski and P. Rakic. Strüngmann Forum Reports, vol. 27, J. R. Lupp, series editor. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-04324-3 13 Functional Properties of Circuits, Cellular Populations, and Areas Kenneth D. Harris, Jennifer M. Groh, James DiCarlo, Pascal Fries, Matthias Kaschube, Gilles Laurent, Jason N. MacLean, David A. McCormick, Gordon Pipa, John H. Reynolds, Andrew B. Schwartz, Terrence J. Sejnowski, Wolf Singer, and Martin Vinck Abstract A central goal of systems neuroscience is to understand how the brain represents and processes information to guide behavior (broadly defi ned as encompassing perception, cognition, and observable outcomes of those mental states through action). These con- cepts have been central to research in this fi eld for at least sixty years, and research efforts have taken a variety of approaches. At this Forum, our discussions focused on what is meant by “functional” and “inter-areal,” what new concepts have emerged over the last several decades, and how we need to update and refresh these concepts and ap- proaches for the coming decade. In this chapter, we consider some of the historical conceptual frameworks that have shaped consideration of neural coding and brain function, with an eye toward what aspects have held up well, what aspects need to be revised, and what new concepts may foster future work. Conceptual frameworks need to be revised periodically lest they become counter- productive and actually blind us to the signifi cance of novel discoveries. -

Breakthroughs in Brain Research with High Performance Computing 1 High Performance Computing Case Study

Breakthroughs in Brain Research with High Performance Computing 1 High Performance Computing Case Study. Breakthroughs in Brain Research with High Performance Computing Breakthroughs in Brain Research with High Performance Computing This publication may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form be- yond copying permitted by sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. copyright law and excerpts by reviewers for the public press, without written permission from the publishers. The Council on Competitiveness is a nonprofit, 501 (c) (3) organization as recognized by the U.S. Internal Revenue Service. The Council’s activities are funded by contributions from its members, foundations, and project contributions. To learn more about the Council on Competitiveness, visit us at www.compete.org. Copyright © 2008 Council on Competitiveness Design: Soulellis Studio This work was supported by The National Science Foundation under grant award #0456129. Printed in the United States of America Breakthroughs in Brain Research with High Performance Computing 1 Breakthroughs in Brain Research with High Performance Computing Researchers at the Salk Institute are using supercomputers at the nearby NSF-funded San Diego Supercomputer Center to investigate how the synapses of the brain work. Their research has the potential to help people suffering from mental disorders such as Alzheimer’s, schizophrenia and manic depressive disorders. In addition, the use of supercomputers is helping to change the very nature of biology – from a science that has relied primarily on observation to a science that relies on high performance computing to achieve previously impossible in-depth quantitative results. To paraphrase Yogi Berra, You can see a lot just by like those in a muscle or gland. -

In the Beginning Please Turn to Page 28

FROM THE EDITOR Mariette DiChristina is editor in chief of Scientific American. Follow her on Twitter @mdichristina sounds so harsh have been beneficial, you ask? To find out, In the Beginning please turn to page 28. The sun’s rays provided vitality for this world. Seeing them There was light. But then what happened? dim temporarily, as they do during a solar eclipse, is aweinspir How did life arise on the third rocky planet orbiting the un ing. It’s been nearly a century since a total solar eclipse has remarkable star at the center of our solar system? Humans crossed the U.S. from coast to coast. Starting on page 54, you’ll have been wondering about the answer to that question prob find that “The Great Solar Eclipse of 2017,” by Jay M. Pasachoff, ably almost as long as we’ve been able to wonder. In recent tells you everything you need to know about this rare event. And decades scientists have made some a companion piece, “1,000 Years of gains in understanding the conceiv Solar Eclipses,” by senior editor Mark able mechanisms, gradually settling Fischetti, with illustrations by senior on a possible picture of our origins graphics editor Jen Christiansen and in the oceans. The idea was that designer Jan Willem Tulp, tells you hydrothermal vents at the bottom of what you will need to know as well. I the seas, protected from cataclysms like to think that the readers of Scien - rending the surface four billion tific American,which turns 172 this years ago, delivered the necessary month, will be enjoying the solar energy and could have sustained the shows well into the future. -

Talking Nets: an Oral History of Neural Networks 6

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Artificial Intelligence 119 (2000) 287–293 Book Review J.A. Anderson and E. Rosenfeld (Eds.), Talking Nets: An Oral History of Neural Networks ✩ Noel E. Sharkey 1 University of Sheffield, Department of Computer Science, Regent Court, 221 Portobello Street, Sheffield S1 4DP, UK Drugs, tragedy, romance, success, misfortune, luck, pathos, bitterness, jealousy and struggle are not words that we expect in a review of an academic book of interviews with some of the great and good of neural network research. But this book is not just concerned with the science and engineering of neural network research as seen in the literature; it deals with the motivation from the childhood and early developments of each of the 17 interviewees and with informal accounts of their scientific endeavours. This is an attempt to get to an understanding of the science through an understanding of the scientists themselves, their schooling, their interests, and their major influences. It is a wonderfully charming book and well worth reading. To maintain the historical sequence of events, the editors have placed the interviews in the order of the birth dates of the interviewees. This works well in many cases but there are some notable exceptions. For example, the Werbos interview is sandwiched between Sejnowski and Hinton when he had actually carried out significant work much earlier. Then there is Leon Cooper who, although fourth oldest, should really belong, historically, at position 12 because he first had a Nobel winning career in Physics. -

Francis Crick's Legacy for Neuroscience

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PubMed Central Open access, freely available online Obituary Francis Crick’s Legacy for Neuroscience: Between the α and the Ω Ralph M. Siegel*, Edward M. Callaway ‘You’, your joys and your sorrows, your memories Hubel and Wiesel wrote of functional new ideas of a theoretical neurology and your ambitions, your sense of personal architectures, embedded in beautiful, to the brain (Marr 1969, 1970). And identity and free will, are in fact no more than almost crystalline structure. The he saw the tragedy of Marr being cut the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells…” comprehension of mind invoked by a off from solving the big problems for —Crick (1994, p. 3) biological mechanism appeared ripe which he was so clearly destined. for the sort of thoughtful, theoretical During those early years, Francis rancis Crick was an evangelical science he had applied to DNA. Francis must have thought that consciousness atheist. He believed that scientifi c was now sixty years old and moved from was tractable—if only the right way of Funderstanding removed the need Cambridge to the Salk Institute in La thinking was brought to bear on it. for religious explanations of natural Jolla, California. Francis began with the Francis’s brain was capable of collecting phenomena. From James Watson’s brightest young minds he could fi nd. and fi ling away many disparate and his early work, the structure of David Marr was a young data, which he could then combine DNA explained the α, the origins of mathematician and physiologist uniquely and imaginatively, leading life. -

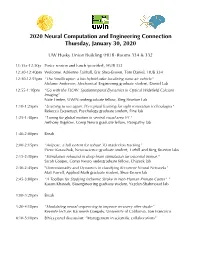

2020 Neural Computation and Engineering Connection Thursday, January 30, 2020

2020 Neural Computation and Engineering Connection Thursday, January 30, 2020 UW Husky Union Building (HUB) Rooms 334 & 332 11:15a-12:30p Poster session and lunch (provided), HUB 332 12:30-12:40pm Welcome: Adrienne Fairhall, Eric Shea-Brown, Tom Daniel, HUB 334 12:40-12:55pm “The Smellicopter: a bio-hybrid odor localizing nano-air vehicle" Melanie Anderson, Mechanical Engineering graduate student, Daniel Lab 12:55-1:10pm "Go with the FLOW: Spatiotemporal Dynamics in Optical Widefield Calcium Imaging” Nate Linden, UWIN undergraduate fellow, Bing Brunton Lab 1:10-1:25pm "Learning to see again: Perceptual learning for sight restoration technologies" Rebecca Esquenazi, Psychology graduate student, Fine lab 1:25-1:40pm "Tuning for global motion in ventral visual area V4 " Anthony Bigelow, Comp Neuro graduate fellow, Pasupathy lab 1:40-2:00pm Break 2:00-2:15pm "Anipose: a full system for robust 3D markerless tracking” Pierre Karaschuk, Neuroscience graduate student, Tuthill and Bing Brunton labs 2:15-2:30pm "Stimulation rebound in deep brain stimulation for essential tremor." Sarah Cooper, Comp Neuro undergraduate fellow, Chizeck lab 2:30-2:45pm "Dimensionality and Dynamics in classifying Recurrent Neural Networks" Matt Farrell, Applied Math graduate student, Shea-Brown lab 2:45-3:00pm "A Toolbox for Studying Ischemic Stroke in Non-Human Primate Cortex" " Karam Khateeb, Bioengineering graduate student, Yazdan-Shahmorad lab 3:00-3:20pm Break 3:20-4:10pm "Modulating neural sequencing to improve recovery after stroke” Keynote lecture: Karunesh -

Developing a 21St Century Neuroscience Workforce: Workshop Summary

This PDF is available from The National Academies Press at http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=21697 Developing a 21st Century Neuroscience Workforce: Workshop Summary ISBN Sheena M. Posey Norris, Christopher Palmer, Clare Stroud, and Bruce M. 978-0-309-36874-2 Altevogt, Rapporteurs; Forum on Neuroscience and Nervous System Disorders; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Institute of Medicine 130 pages 6 x 9 PAPERBACK (2015) Visit the National Academies Press online and register for... Instant access to free PDF downloads of titles from the NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES NATIONAL ACADEMY OF ENGINEERING INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL 10% off print titles Custom notification of new releases in your field of interest Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Request reprint permission for this book Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Developing a 21st Century Neuroscience Workforce: Workshop Summary DEVELOPING A 21ST CENTURY NEUROSCIENCE WORKFORCE WORKSHOP SUMMARY Sheena M. Posey Norris, Christopher Palmer, Clare Stroud, and Bruce M. Altevogt, Rapporteurs Forum on Neuroscience and Nervous System Disorders Board on Health Sciences Policy PREPUBLICATION COPY: UNCORRECTED PROOFS Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Developing a 21st Century Neuroscience Workforce: Workshop Summary THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS • 500 Fifth Street, NW • Washington, DC 20001 NOTICE: The workshop that is the subject of this workshop summary was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine. -

NIH and the BRAIN Initiative Francis S

NIH and the BRAIN Initiative Francis S. Collins, M.D., Ph.D. Director, National Institutes of Health Meeting of the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology May 3, 2013 A Bold New Initiative in American science Learning the language of the brain The Need Is Great . Brain disorders: #1 source of disability in U.S. – > 100 million Americans affected . Rates are increasing: autism, Alzheimer’s disease, and in our soldiers PTSD and TBI The Need Is Great . Brain disorders: #1 source of disability in U.S. – > 100 million Americans affected . Rates are increasing: autism, Alzheimer’s disease, and in our soldiers PTSD and TBI . Costs are increasing: annual cost of dementia ~$200B – Already equals cost of cancer and heart disease The Science Is Ready . Progress in neuroscience is yielding new insights into brain structure, function . Progress in optics, genetics, nanotechnology, informatics, etc. is rapidly advancing design of new tools Advances in Understanding Brain Structure Brainbow (Livet et al., 2007) Human Connectome Before After CLARITY After CLARITY (Wedeen et al., 2012) CLARITY (Chung et al., 2013) Advances in Understanding Brain Structure: CLARITY 3D analysis of an intact mouse hippocampus Advances in Understanding Brain Function Zebra fish larvae (Ahrens et al., 2013) Advances in Understanding Brain Function Zebra fish larvae (Ahrens et al., 2013) 1202 hipp neurons (Schnitzer laboratory) Advances in Understanding Brain Function Zebra fish larvae (Ahrens et al., 2013) 21 transient functional modes (K. Ugurbil 2012) 1202 hipp neurons (Schnitzer laboratory) Making the Next Leap . Today: despite advances, we are still limited in our understanding of how the brain processes information . -

A Timeline of Artificial Intelligence

A Timeline of Artificial Intelligence by piero scaruffi | www.scaruffi.com All of these events are explained in my book "Intelligence is not Artificial". TM, ®, Copyright © 1996-2019 Piero Scaruffi except pictures. All rights reserved. 1960: Henry Kelley and Arthur Bryson invent backpropagation 1960: Donald Michie's reinforcement-learning system MENACE 1960: Hilary Putnam's Computational Functionalism ("Minds and Machines") 1960: The backpropagation algorithm 1961: Melvin Maron's "Automatic Indexing" 1961: Karl Steinbuch's neural network Lernmatrix 1961: Leonard Scheer's and John Chubbuck's Mod I (1962) and Mod II (1964) 1961: Space General Corporation's lunar explorer 1962: IBM's "Shoebox" for speech recognition 1962: AMF's "VersaTran" robot 1963: John McCarthy moves to Stanford and founds the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (SAIL) 1963: Lawrence Roberts' "Machine Perception of Three Dimensional Solids", the birth of computer vision 1963: Jim Slagle writes a program for symbolic integration (calculus) 1963: Edward Feigenbaum's and Julian Feldman's "Computers and Thought" 1963: Vladimir Vapnik's "support-vector networks" (SVN) 1964: Peter Toma demonstrates the machine-translation system Systran 1965: Irving John Good (Isidore Jacob Gudak) speculates about "ultraintelligent machines" (the "singularity") 1965: The Case Institute of Technology builds the first computer-controlled robotic arm 1965: Ed Feigenbaum's Dendral expert system 1965: Gordon Moore's Law of exponential progress in integrated circuits ("Cramming more components -

How to Represent Part-Whole Hierarchies in a Neural Network

How to represent part-whole hierarchies in a neural network Geoffrey Hinton Google Research & The Vector Institute & Department of Computer Science University of Toronto February 22, 2021 Abstract This paper does not describe a working system. Instead, it presents a single idea about representation which allows advances made by several different groups to be combined into an imaginary system called GLOM1. The advances include transformers, neural fields, contrastive representa- tion learning, distillation and capsules. GLOM answers the question: How can a neural network with a fixed architecture parse an image into a part- whole hierarchy which has a different structure for each image? The idea is simply to use islands of identical vectors to represent the nodes in the parse tree. If GLOM can be made to work, it should significantly improve the interpretability of the representations produced by transformer-like systems when applied to vision or language. 1 Overview of the idea arXiv:2102.12627v1 [cs.CV] 25 Feb 2021 There is strong psychological evidence that people parse visual scenes into part- whole hierarchies and model the viewpoint-invariant spatial relationship be- tween a part and a whole as the coordinate transformation between intrinsic coordinate frames that they assign to the part and the whole [Hinton, 1979]. If we want to make neural networks that understand images in the same way as people do, we need to figure out how neural networks can represent part-whole 1GLOM is derived from the slang "glom together" which may derive from the word "ag- glomerate". 1 hierarchies. This is difficult because a real neural network cannot dynamically allocate a group of neurons to represent a node in a parse tree2.