An Examination of the Executive Tools Used To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Items-In-United Nations Associations (Unas) in the World

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page 14 Date 21/06/2006 Time 11:29:23 AM S-0990-0002-07-00001 Expanded Number S-0990-0002-07-00001 Items-in-United Nations Associations (UNAs) in the World Date Created 22/12/1973 Record Type Archival Item Container S-0990-0002: United Nations Emergency and Relief Operations Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit *RA/IL/SG bf .KH/ PMG/ T$/ MP cc: SG 21 October 75 X. Lehmann/sg 38O2 87S EOSG OMNIPRESS LONDON (ENGLAND) \ POPOVIC REFERENCE YOUR 317 TO HENUIG, MESSAGE PROM SECGEH ON ANNIVERSARY OF WINSCHOTElJt UK ^TOWKf WAS MAILED BY US OCTOBER 17 MSD CABLED TO DE BOER BY NETHERLANDS PERMANENT MISSION DODAY AS TELEPHONE MESSAGE FROM SECGEN NOT POSSIBLE. REGARDS, AHMED Rafeeuddin Ahmed ti at r >»"• f REFCREHCX & SEPfSMiS!? LETTS8 ' AS80CXATXOK COPIES Y0BR OFFICE PB0P8SW f © ¥IJI$0H0TE8 IfH 10^8* &fJT£H AMBASSADOR KADFE1AW UNDSETAKIMG sur THEY ®0^i APPRI OIATI sn©Hf SABLS& SECSSH es OS WITS ®&M XKSTlATS9ff GEREf&DtES LAST 88 BAY IF M01E COKVEltXEtir atrEETx ti&s TIKI at$« BEKALr« — -— S • Sit ' " 9, 20 osfc&fee* This is the text of the Secretary-General's message sent to Ms. Gerry M. de Boer on October £ waa very interested to learn of your plans to celebsrate United Nations Bay on S4 October, and the first anniversary of Winschoten ti«H. Town. I would like to congratulate the Hetlierlanfis United Nations Association and the Winschoten Committee on this imaginative programme. It is particularly rewarding and encouraging when citizens involve themselves positively ani constructively in the concerns of the United Nations. -

July 2021.Cdr

St. Norbert Campus Chronicles Vol -2, Issue 2 St. Norbert School, CBSE Affliation No: 831041, Chowhalli, T. Narasipura - 571124 July - 2021 World Day for International Justice - By Amruth world as part of an effort to recognize fact that on the same day the year 2010 decided to celebrate July the system of international criminal International Criminal Court was 17 as World Day for International justice and for the people to pay established. The International Justice. In addition, 'Social Justice in attention to serious crimes happening Criminal Court which was the Digital Economy' has been around the world. This day is also established on this day along with adopted as this year's theme to known as international criminal ratification of the Rome Statute is a celebrate the World Day for "True peace is not merely the absence justice day, which aims at the mechanism to bring to book grave International Justice. The theme of of tension but it is the presence of importance of bringing justice to crimes and ensure harsh punishment Social Justice in the Digital Justice", famous quotation by Martin people against crimes, wars and for criminals resorting to crimes at Economy also points to the large Luther King which means that genocides. The world celebrates the the international level. Apart from digital divide between haves and genuine peace requires the presence World Day for International Justice paying homage to the people and have nots. The topic is extremely of Justice, but the absence of conflict celebrating the virtues of justice organisations committed to the cause relevant for this year as with the swift and violence. -

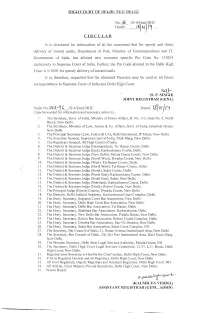

Dat~D: ~: -~--L~I~(I' ~- CIRCULAR

HIGH COURT OJ1' DELHI: NEW DELHI No.3G IG-4/GcnllDHC Dat~d: ~: -~--L~I~(I' ~- CIRCULAR It is circulated for information of all the concerned that for speedy and direct delivery of inward mails, Department of Post, Ministry of Communications and IT, Government of India, has allotted new customer specific Pin Code No. 11020 1 exclusively 10 Supreme Court of India. Further, the Pin Code allotted to the Delhi High Court is 110503 for speedy delivery of inward mails. It is, therefore, requested that the aforesaid Pincodes may be used in all future corrcspontlence to Supreme Court of India and Delhi High Court. ~/- (S. P. SINGH) JOINT REGISTRAR (GENL) Endst No. '(~~3 ~_/G-4/Genl/DHC Dated. (8)6j ) '- ~ _ Copy forwarded for information and necessary action to: l. The Secretary, Govt. of India, Ministry of Home Affairs, R. No. 113, Gate No.4, North Block, New Delhi. 2. The Secretary, M,inistry of Law, Justice & Co. Affairs, Govt. ofIndia, Jaisalmer Housc, New Delhi. ,., ..1. The Principal Secretary (Law, Justice & LA), Delhi Secretariat, IP Estate, New Delhi. 4. The Secretary General, Supreme COllli ofIndia, Tilak Marg, New Delhi. 5. The Registrars General, All High Courts of India. 6. The District & Sessions Judge (Headqualicrs), Tis Hazari Courts, Delhi. 7. The District & Sessions Judge (East), Karkardooma COLllis, Delhi. 8. The District & Sessions Judge (New Delhi), Patiala House COLllis, New Delhi. 9. The District & Sessions Judge (South West), Dwarka Co Lllis, New Delhi. 10. The District & Sessions Judge (West), Tis Hazari COLllis, Delhi. ll. The District & Sessions Judge (NOlib West), Tis Hazari COlllis, Delhi. -

Speech by Shri Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed, the President of India 13Th Convocation of the INDIAN ACADEMY of MEDICAL SCIENCES, New Delhi, January 03, 1976

Speech by Shri Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed, The President of India 13th Convocation of the INDIAN ACADEMY OF MEDICAL SCIENCES, New Delhi, January 03, 1976 I deem it a privilege to have been invited to be the Chief Guest at the 13th Convocation of the Indian Academy of Medical Sciences. The Indian Academy of Medical Sciences is an association of the highest talents in the field of medical sciences. I am happy to note that the Academy is zealously striving to promote excellence in the field of medical research and education and that it plays a significant role in establishing an intellectual climate for the conduct of research in the specialized areas of medical science. India is committed to improving the quality of life and raising the standard of living of its people. To bring about this social transformation, we have adopted that method of planned development. Development, to my mind, means more the development of human quality and mental and physical resources rather than merely of material resources. If we wish individuals to have a qualitatively better life, the basic amenities incorporated in the scheme of development must cover areas of public health and health education. Science and technology will help us in solving the formidable problems facing us in the field of health and medical care only if we use them in the proper matrix and adapt them to our needs. Fight against death and disease has today become a global concern and the scientific communities of the developing world have to collectively evolve a strategy to face the spectra of disease, under‐nourishment and over population. -

India Freedom Fighters' Organisation

A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of Political Pamphlets from the Indian Subcontinent Part 5: Political Parties, Special Interest Groups, and Indian Internal Politics UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of POLITICAL PAMPHLETS FROM THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT PART 5: POLITICAL PARTIES, SPECIAL INTEREST GROUPS, AND INDIAN INTERNAL POLITICS Editorial Adviser Granville Austin Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfiche project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Indian political pamphlets [microform] microfiche Accompanied by printed guide. Includes bibliographical references. Content: pt. 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups—pt. 2. Indian Internal Politics—[etc.]—pt. 5. Political Parties, Special Interest Groups, and Indian Internal Politics ISBN 1-55655-829-5 (microfiche) 1. Political parties—India. I. UPA Academic Editions (Firm) JQ298.A1 I527 2000 <MicRR> 324.254—dc20 89-70560 CIP Copyright © 2000 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-829-5. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................. vii Source Note ............................................................................................................................. xi Reference Bibliography Series 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups Organization Accession # -

FOREWORD the Need to Prepare a Clear and Comprehensive Document

FOREWORD The need to prepare a clear and comprehensive document on the Punjab problem has been felt by the Sikh community for a very long time. With the release of this White Paper, the S.G.P.C. has fulfilled this long-felt need of the community. It takes cognisance of all aspects of the problem-historical, socio-economic, political and ideological. The approach of the Indian Government has been too partisan and negative to take into account a complete perspective of the multidimensional problem. The government White Paper focusses only on the law and order aspect, deliberately ignoring a careful examination of the issues and processes that have compounded the problem. The state, with its aggressive publicity organs, has often, tried to conceal the basic facts and withhold the genocide of the Sikhs conducted in Punjab in the name of restoring peace. Operation Black Out, conducted in full collaboration with the media, has often led to the circulation of one-sided versions of the problem, adding to the poignancy of the plight of the Sikhs. Record has to be put straight for people and posterity. But it requires volumes to make a full disclosure of the long history of betrayal, discrimination, political trickery, murky intrigues, phoney negotiations and repression which has led to blood and tears, trauma and torture for the Sikhs over the past five decades. Moreover, it is not possible to gather full information, without access to government records. This document has been prepared on the basis of available evidence to awaken the voices of all those who love justice to the understanding of the Sikh point of view. -

Development of Regional Politics in India: a Study of Coalition of Political Partib in Uhar Pradesh

DEVELOPMENT OF REGIONAL POLITICS IN INDIA: A STUDY OF COALITION OF POLITICAL PARTIB IN UHAR PRADESH ABSTRACT THB8IS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF fioctor of ^IHloKoplip IN POLITICAL SaENCE BY TABRBZ AbAM Un<l«r tht SupMvMon of PBOP. N. SUBSAHNANYAN DEPARTMENT Of POLITICAL SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALI6ARH (INDIA) The thesis "Development of Regional Politics in India : A Study of Coalition of Political Parties in Uttar Pradesh" is an attempt to analyse the multifarious dimensions, actions and interactions of the politics of regionalism in India and the coalition politics in Uttar Pradesh. The study in general tries to comprehend regional awareness and consciousness in its content and form in the Indian sub-continent, with a special study of coalition politics in UP., which of late has presented a picture of chaos, conflict and crise-cross, syndrome of democracy. Regionalism is a manifestation of socio-economic and cultural forces in a large setup. It is a psychic phenomenon where a particular part faces a psyche of relative deprivation. It also involves a quest for identity projecting one's own language, religion and culture. In the economic context, it is a search for an intermediate control system between the centre and the peripheries for gains in the national arena. The study begins with the analysis of conceptual aspect of regionalism in India. It also traces its historical roots and examine the role played by Indian National Congress. The phenomenon of regionalism is a pre-independence problem which has got many manifestation after independence. It is also asserted that regionalism is a complex amalgam of geo-cultural, economic, historical and psychic factors. -

Dated 9Th October, 2018 Reg. Elevation

SUPREME COURT OF INDIA This file relates to the proposal for appointment of following seven Advocates, as Judges of the Kerala High Court: 1. Shri V.G.Arun, 2. Shri N. Nagaresh, 3. Shri P. Gopal, 4. Shri P.V.Kunhikrishnan, 5. Shri S. Ramesh, 6. Shri Viju Abraham, 7. Shri George Varghese. The above recommendation made by the then Chief Justice of the th Kerala High Court on 7 March, 2018, in consultation with his two senior- most colleagues, has the concurrence of the State Government of Kerala. In order to ascertain suitability of the above-named recommendees for elevation to the High Court, we have consulted our colleagues conversant with the affairs of the Kerala High Court. Copies of letters of opinion of our consultee-colleagues received in this regard are placed below. For purpose of assessing merit and suitability of the above-named recommendees for elevation to the High Court, we have carefully scrutinized the material placed in the file including the observations made by the Department of Justice therein. Apart from this, we invited all the above-named recommendees with a view to have an interaction with them. On the basis of interaction and having regard to all relevant factors, the Collegium is of the considered view that S/Shri (1) V.G.Arun, (2) N. Nagaresh, and (3) P.V.Kunhikrishnan, Advocates (mentioned at Sl. Nos. 1, 2 and 4 above) are suitable for being appointed as Judges of the Kerala High Court. As regards S/Shri S. Ramesh, Viju Abraham, and George Varghese, Advocates (mentioned at Sl. -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

Oram, Shri Jual

For official use only LOK SABHA DEBATES ON THE CONSTITUTION (ONE HUNDRED AND TWENTY FIRST AMENDMENT) BILL, 2014 (Insertion of new articles 124A, 124B and 124C) AND THE NATIONAL JUDICIAL APPOINTMENTS COMMISSION BILL, 2014 (Seal) LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI EDITORIAL BOARD P.K. Grover Secretary General Lok Sabha R.K. Jain Joint Secretary Vandna Trivedi Director Parmjeet Karolia Additional Director J.B.S. Rawat Joint Director Pratibha Kashyap Assistant Editor © 2014 Lok Sabha Secretariat None of the material may be copied, reproduced, distributed, republished, downloaded, displayed, posted or transmitted in any form or by any means, including but not limited to, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Lok Sabha Secretariat. However, the material can be displayed, copied, distributed and downloaded for personal, non-commercial use only, provided the material is not modified and all copyright and other proprietary notices contained in the material are retained. CONTENTS Tuesday/Wednesday, August 12/13, 2014/Shravana 21/22, 1936 (Saka) Pages THE CONSTITUTION (ONE HUNDRED AND TWENTY- 1-105 FIRST AMENDMENT) BILL, 2014 (Insertion of new articles 124A, 124B and 124C) AND THE NATIONAL JUDICIAL APPOINTMENTS COMMISSION BILL, 2014 Motion to consider 1-2 Shri Ravi Shankar Prasad 2-13, 77-99 Shri M. Veerappa Moily 16-26 Shri S.S. Ahluwalia 26-31 Dr. M. Thambidurai 31-38 Shri Kalyan Banerjee 39-46 Shri Bhartruhari Mahtab 46-52 Shri Anandrao Adsul 52-53 Shri B. Vinod Kumar 53-55 Dr. A. Sampath 55-59 Shri Ram Vilas Paswan 60-63 Shri Dharmendra Yadav 63-64 Shri Rajesh Ranjan 65-66 Dr. -

Securing the Independence of the Judiciary-The Indian Experience

SECURING THE INDEPENDENCE OF THE JUDICIARY-THE INDIAN EXPERIENCE M. P. Singh* We have provided in the Constitution for a judiciary which will be independent. It is difficult to suggest anything more to make the Supreme Court and the High Courts independent of the influence of the executive. There is an attempt made in the Constitutionto make even the lowerjudiciary independent of any outside or extraneous influence.' There can be no difference of opinion in the House that ourjudiciary must both be independent of the executive and must also be competent in itself And the question is how these two objects could be secured.' I. INTRODUCTION An independent judiciary is necessary for a free society and a constitutional democracy. It ensures the rule of law and realization of human rights and also the prosperity and stability of a society.3 The independence of the judiciary is normally assured through the constitution but it may also be assured through legislation, conventions, and other suitable norms and practices. Following the Constitution of the United States, almost all constitutions lay down at least the foundations, if not the entire edifices, of an * Professor of Law, University of Delhi, India. The author was a Visiting Fellow, Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and Public International Law, Heidelberg, Germany. I am grateful to the University of Delhi for granting me leave and to the Max Planck Institute for giving me the research fellowship and excellent facilities to work. I am also grateful to Dieter Conrad, Jill Cottrell, K. I. Vibute, and Rahamatullah Khan for their comments. -

(Ph. D. Thesis) March, 1990 Takako Hirose

THE SINGLE DOMINANT PARTY SYSTEM AND POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT: CASE STUDIES OF INDIA AND JAPAN (Ph. D. Thesis) March, 1990 Takako Hirose ABSTRACT This is an attempt to compare the processes of political development in India and Japan. The two states have been chosen because of some common features: these two Asian countries have preserved their own cultures despite certain degrees of modernisation; both have maintained a system of parliamentary democracy based on free electoral competition and universal franchise; both political systems are characterised by the prevalence of a single dominant party system. The primary objective of this analysis is to test the relevance of Western theories of political development. Three hypotheses have been formulated: on the relationship between economic growth and social modernisation on the one hand and political development on the other; on the establishment of a "nation-state" as a prerequisite for political development; and on the relationship between political stability and political development. For the purpose of testing these hypotheses, the two countries serve as good models because of their vastly different socio-economic conditions: the different levels of modernisation and economic growth; the homogeneity- heterogeneity dichotomy; and the frequency of political conflict. In conclusion, Japan is an apoliticised society in consequence of the imbalance between its political and economic development. By contrast, the Indian political system is characterised by an ever-increasing demand for - 2 - participation, with which current levels of institutionalisation cannot keep pace. The respective single dominant parties have thus played opposing roles, i.e. of apoliticising society in the case of Japan while encouraging participation in that of India.