William Marshal a Great Knight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1066-1272 Eastern Sussex Under the Norman and Angevin Kings of England

1066-1272 Eastern Sussex under the Norman and Angevin kings of England From the Battle of Hastings through the accession of William II until the death of Henry II Introduction In this paper the relationships of the post-Conquest kings of England to Battle and eastern Sussex between 1087 and 1272 are explored. The area ‘eastern Sussex’ corresponds to that described as ‘1066 Country’ in modern tourism parlance and covers the area west to east from Pevensey to Kent and south to north from the English Channel coast to Kent. Clearly the general histories of the monarchs and associated events must be severely truncated in such local studies. Hopefully, to maintain relevance, just enough information is given to link the key points of the local histories to the kings, and events surrounding the kings. Also in studies which have focal local interest there can inevitably be large time gaps between events, and some local events of really momentous concern can only be described from very little information. Other smaller events can be overwhelmed by detail, particularly later in the sequence, when more detailed records become available and ‘editing down’ is required to keep some basic perspective. The work is drawn from wide sources and as much as possible the text has been cross referenced between different works. A list of sources is given at the end of the sequence. Throughout the texts ‘Winchelsea’ refers to ‘Old Winchelsea’ which may have only been a small fishing village in 1066, but by the 1200s had become a sizable and important, if somewhat independently minded and anarchic town, which stood on a large shingle bank east of the present Winchelsea, possibly just south of where Camber castle still stands today. -

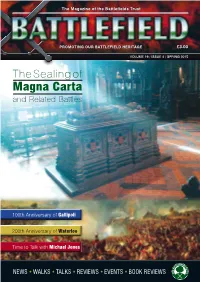

Battlefields 2015 Spring Issue

The Magazine of the Battlefields Trust PROMOTING OUR BATTLEFIELD HERITAGE £3.00 VOLUME 19 / ISSUE 4 / SPRING 2015 The Sealing of Magna Carta and Related Battles 100th Anniversary of Gallipoli 200th Anniversary of Waterloo Time to Talk with Michael Jones NEWS • WALKS • TALKS • REVIEWS • EVENTS • BOOK REVIEWS The Agincourt Archer On 25 October 1415 Henry V with a small English army of 6,000 men, made up mainly of archers, found himself trapped by a French army of 24,000. Although outnumbered 4 to 1 in the battle that followed the French were completely routed. It was one of the most remarkable victories in British history. The Battlefields Trust is commemorating the 600th anniversary of this famous battle by proudly offering a limited edition of numbered prints of well-known actor, longbow expert and Battlefields Trust President and Patron, Robert Hardy, portrayed as an English archer at the Battle of Agincourt. The prints are A4 sized and are being sold for £20.00, including Post & Packing. This is a unique opportunity; the prints are a strictly limited edition, so to avoid disappointment contact Howard Simmons either on email howard@ bhprassociates.co.uk or ring 07734 506214 (please leave a message if necessary) as soon as possible for further details. All proceeds go to support the Battlefields Trust. Battlefields Trust Protecting, interpreting and presenting battlefields as historical and educational The resources Agincourt Archer Spring 2015 Editorial Editors’ Letter Harvey Watson Welcome to the spring 2015 issue of Battlefield. At exactly 11.20 a.m. on Sunday 18 June 07818 853 385 1815 the artillery batteries of Napoleon’s army opened fire on the Duke Wellington’s combined army of British, Dutch and German troops who held a defensive position close Chris May to the village of Waterloo. -

Ncoln Castle and the Battle of Lincoln 1217

Lincoln Castle N 1217 W E A year that shook S Lincoln! Come and meet the characters of the Battle of Lincoln Lady Nichola Sir William Falkes de Edith, a Count of Bishop of de la Haye Marshall Bréauté servant Perche Winchester Take a virtual walk of the walls of Lincoln Castle and find out about the Battle of Lincoln 1217 Start above the East Gate by meeting Lady Nichola de la Haye and then follow the map anti-clockwise to find out about the Battle of Lincoln. ü Look at each symbol on the map and then think about being on the walls at that position. ü Match the symbol with the character. ü At each point on this virtual trail read out the story of the Battle of Lincoln based on the characters. ü Answer the questions about each character. ü There are suggested activities to do at the end of the virtual tour. Lady Nichola de la Haye Early evening on Friday 19th May 2017 Lady Nichola de la Haye greets you as she looks over the battlements of the East Gate of Lincoln Castle. She is the brave sixty year old noble woman and Constable who, just last year, had offered the keys to the castle back to King John. She told him she was too old to continue and thought he would choose someone else to defend the castle in the coming siege. King John refused as he had great faith in her. This proved correct as she gained a truce with the rebel forces in Lincoln in the summer of 1216. -

GENDER in HISTORY

Susan M. Johns - 9781526137555 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/29/2021 10:23:54PM via free access GENDER in HISTORY Series editors: Pam Sharpe, Patricia Skinner and Penny Summerfield The expansion of research into the history of women and gender since the 1970s has changed the face of history. Using the insights of feminist theory and of historians of women, gender historians have explored the configura- tion in the past of gender identities and relations between the sexes. They have also investigated the history of sexuality and family relations, and analysed ideas and ideals of masculinity and femininity. Yet gender history has not abandoned the original, inspirational project of women’s history: to recover and reveal the lived experience of women in the past and the present. The series Gender in History provides a forum for these developments. Its historical coverage extends from the medieval to the modern periods, and its geographical scope encompasses not only Europe and North America but all corners of the globe. The series aims to investigate the social and cultural constructions of gender in historical sources, as well as the gendering of historical discourse itself. It embraces both detailed case studies of spe- cific regions or periods, and broader treatments of major themes. Gender in History titles are designed to meet the needs of both scholars and students working in this dynamic area of historical research. Noblewomen, aristocracy and power in the twelfth-century Anglo-Norman realm i Susan M. Johns - 9781526137555 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/29/2021 10:23:54PM via free access Seal of Alice, Countess of Northampton (1140–60, Egerton Ch.431). -

Strickland, M.J. Against the Lord's Anointed: Aspects of Warfare and Baronial Rebellion in England and Normandy 1075-1265

Strickland, M.J. Against the Lord's anointed: aspects of warfare and baronial rebellion in England and Normandy 1075-1265. In Garnett, G. and Hudson, J. (Eds) Law and government in medieval England and Normandy: essays in honour of Sir James Holt, Chap 3, pages pp. 56-79. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1994) http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/4579/ 28th August 2008 Glasgow ePrints Service https://eprints.gla.ac.uk Against the Lord's anointed: aspects of warfare and baronial rebellion in England and Normandy, 1075-1265 Matthew Strickland For who can stretch forth his hand against the Lord's anointed and be guiltless?1 Within a framework of arbitrary, monarchical government, baronial rebellion formed one of the principal means both of expressing political discontent and of seeking the redress of grievances. So frequent were its manifestations that hostilities arising from armed opposition to the crown account for a large proportion of warfare waged in England, Normandy and the continental Angevin lands in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. The subject of revolt, lying as it does close to the heart of crown- baronial interaction, is as fundamental as it is multifaceted, embracing many issues of central importance, for example the legal status of revolt and its complex relationship with concepts of treason; the nature of homage and fealty, and the question of the revocability of these bonds in relation to the king; the growth in notions of the crown, of maiestas and the influence of Roman Law; political theories of resistance and obedience; the limitations imposed by ties of kinship and of political sympathy among the baronage on the king's ability to suppress revolt and to enforce effective punishment; and the extent of the king's logistical and military superiority. -

Down Upon the Fold: Mercenaries in the Twelfth Century. Steven Wayne Isaac Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1998 Down Upon the Fold: Mercenaries in the Twelfth Century. Steven Wayne Isaac Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Isaac, Steven Wayne, "Down Upon the Fold: Mercenaries in the Twelfth eC ntury." (1998). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6784. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6784 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Lincoln Castle and Magna Carta~ Here at Lincoln Castle We Have the Privilege to Look After One of the Four Remaining 1215 Magna Cartas

~ Lincoln Castle and Magna Carta~ Here at Lincoln Castle we have the privilege to look after one of the four remaining 1215 Magna Cartas. The Magna Carta is a document written in black ink on parchment. Scribes would use feather pens and couldn’t make any mistakes! ~ King John ~ On the 27th May 1199 John became King of England. He was the eighth child of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. As the youngest boy, John had not expected to be king. His father didn't give him much land to rule so he was often called Lackland. He probably thought he would have a career in the Church and was taught by the Abbot of Reading. However, his elder brothers died young and his sisters were unable to inherit, so John became King. His parents had built up a collection of land called the Angevin Empire. When he became King, John lost nearly half of the Angevin Empire, mainly in France. In an attempt to get the land back, John demanded more and more taxes, men and resources from the English barons. ~ Magna Carta ~ The barons were very unhappy and wanted John to treat them fairly. In 1215, with the help of Stephen Langton the Archbishop of Canterbury, they put together a Charter of Liberties and confronted the King. On 15th June 1215 King John accepted the charter by adding his royal seal to it. On the left you can see John’s seal, showing him on horseback. This charter was sent out to all the cathedral cities in England. -

A Lost Abbey in Medieval Senghenydd and the Transformation of the Church in South Wales

The Problem of Pendar: a lost abbey in medieval Senghenydd and the transformation of the church in South Wales ‘A thesis submitted to the University of Wales Lampeter in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy’ 2015 Paul Anthony Watkins The Problem of Pendar: a lost abbey in medieval Senghenydd and the transformation of the church in South Wales List of figures Acknowledgements Introduction Chapter I: The Problem of the Abbey of Pendar: the documentary evidence The ‘problem’ and the historiography The Pendar charters The problem of dating Who was Brother Meilyr? Chapter II: The Problem of Pendar: the evidence of the landscape Mapping the charter The archaeology of the charter area The evidence of place names Conclusion Chapter III: The Native Lords of Glamorgan, Senghenydd and Gwynllwg The native lords of Glamorgan The Lords of Senghenydd The kingdoms of Deheubarth, Caerleon and Gwynllŵg Conclusion: Chapter IV: The Earls of Gloucester and Lands of Glamorgan Robert fitz Hamo and the establishment of Norman power in south Wales The followers of Robert fitz Hamo Robert de la Haye The family of de Londres The earls of Gloucester Robert, earl of Gloucester William, earl of Gloucester King John The de Clare earls Hugh le Despencer Conclusion Chapter V: The changes made by immigrant lordship on the church in South East Wales in the early years of the conquest The Pre-Norman church Changes made by Immigrant Lordships Tewkesbury Abbey Gloucester Abbey and its dependency at Ewenny Glastonbury Abbey The Alien Priories St Augustine’s Abbey, Bristol The church under native lordship Conclusion Conclusion Bibliography Appendices Figures and Maps I.1 Copy of Manuscript Penrice and Margam 10 supplied by the National Library of Wales. -

Battle, Eastern Sussex and the Early Norman and Angevin Kings of England

Battle, eastern Sussex and the early Norman and Angevin kings of England William II - BL Harley 4205 f. 1v From the accession of William II until the death of Henry III 1087-1272 Henry III - BL Harley 4205 f. 4v Introduction In these papers the relationships of the kings of England to Battle and eastern Sussex between 1087 and 1272 are explored. The area ‘eastern Sussex’ corresponds to that described as ‘1066 Country’ in modern tourism parlance and covers the area west to east from Pevensey to Kent and south to north from the English Channel coast to Kent. Clearly the general histories of the monarchs and associated events must be severely truncated in such local studies. Hopefully, to maintain relevance, just enough information is given to link the key points of the local histories to the kings, and events surrounding the kings. Also in studies which have focal local interest there can inevitably be large time gaps between events, and some local events of really momentous concern can only be described from very little information. Other smaller events can be overwhelmed by detail, particularly later in the sequence, when more detailed records become available when ‘editing down’ is required to keep some basic perspective. The work is drawn from wide sources and as much as possible the text has been cross referenced between different works. A list of sources is given at the end of the sequence. Throughout the texts ‘Winchelsea’ refers to ‘Old Winchelsea’ which may have only been a small fishing village in 1066, but by the 1200s had become a sizable and important, if somewhat independently minded and anarchic town, which stood on a large shingle bank east of the present Winchelsea, possibly just south of where Camber castle still stands today. -

Magna Carta Maquettes

Magna Carta and the Canterbury maquettes © Bob Collins 2015 BOB COLLINS APRIL 2011 Magna Carta and the Canterbury maquettes The Magna Carta (Great Charter), issued on June 15th, 1215, is the most famous symbol of the power struggle between John, King of England, and several of the ruling Barons. Sealed by the King at Runnymede near Windsor Castle, it specified that the subject had certain liberties that the state could not interfere with, such as the right of a freeman to be tried by due process of law. The charter was adapted and reissued many times, but some of its conditions still remain part of the law today. King John, the youngest son of King Henry II, and brother to King Richard I “The Lionheart”, succeeded to the throne in 1199. He quickly alienated both the Church and many of the powerful Barons of England due to his arbitrary rule, heavy taxation, and military failures that lost most of the English lands in France. Although a number of the Barons remained loyal, many who had suffered from John’s actions moved against him and forced him to submit to the terms of their charter, which placed limits on the royal authority. Neither side expected to abide by it, and a civil war (known as the First Barons’ War) quickly ensued. The rebel Barons’ ultimate aim was to remove the King, even inviting the French Prince Louis to come and rule in his place, but John’s death in 1216 and a French military defeat at Lincoln by the loyalist camp the following year put paid to the plan. -

Schools Educational Resource Pack Key Stage 3 Acknowledgements

SCHOOLS EDUCATIONAL RESOURCE PACK KEY STAGE 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS These resources have been compiled by Professor Louise Wilkinson of Canterbury Christ Church University as part of The Magna Carta Project, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council of the United Kingdom. Professor Wilkinson is grateful to Dr Sophie Ambler and Dr Henry Summerson for their helpful comments and suggestions. The Magna Carta Project also extends its thanks to Dr Claire Breay of the British Library, for directing the project to the use of images within the public domain on the British Library’s Online Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts: http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/searchSimple.asp. and to Mrs Cressida Williams, the Canterbury Cathedral Archivist, and the staff of Canterbury Cathedral Library and Archives for their assistance and support. The images of King John’s great seal for the Unit 1 worksheet are reproduced here by kind permission of the Dean and Chapter of Canterbury Cathedral. As far as possible, we have tried to ensure that all other images used in these resources are in the public domain or are issued under a Creative Commons licence by their originators. INFORMATION FOR TEACHERS This educational resource pack has been devised with reference to the aims and attainment targets of ‘Programmes of study for History’ at Key Stage 3, which forms part of the National Curriculum in England and are available here: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/239075/SECONDARY_ national_curriculum_-_History.pdf The lesson plans and class activities are designed to assist with teaching on ‘the development of Church, state and society in Medieval Britain 1066-1509’. -

Fighting Norman Bishops and Clergy Timothy Robert Martin St

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Culminating Projects in History Department of History 6-2018 Miter and Sword: Fighting Norman Bishops and Clergy Timothy Robert Martin St. Cloud State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/hist_etds Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Timothy Robert, "Miter and Sword: Fighting Norman Bishops and Clergy" (2018). Culminating Projects in History. 16. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/hist_etds/16 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Culminating Projects in History by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Miter and Sword: Fighting Norman Bishops and Clergy by Timothy R. Martin A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of St. Cloud State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History June, 2018 Thesis Committee: Maureen O’Brien, Chairperson Marie Seong-Hak Kim Glenn Davis 2 Abstract This thesis examines Norman bishops and abbots, and their involvement in warfare, either as armed combatants, or commanders of military forces in Normandy, and later in England after William the Conquerors invasion in 1066. While it focuses primarily on the roles of the secular bishops, other relevant accounts of martial feats by other Norman militant