Rafael Guastavino and the Boston Public Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

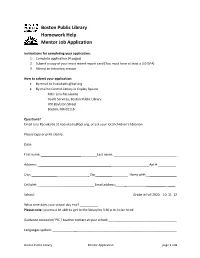

Boston Public Library Homework Help Mentor Job Application

Boston Public Library Homework Help Mentor Job Application Instructions for completing your application: 1. Complete application (4 pages) 2. Submit a copy of your most recent report card (You must have at least a 3.0 GPA) 3. Attend an interview session How to submit your application: • By email to [email protected] • By mail to Central Library in Copley Square Attn: Lina Raciukaitis Youth Services, Boston Public Library 700 Boylston Street Boston, MA 02116 Questions? Email Lina Raciukaitis at [email protected], or ask your local children’s librarian. Please type or print clearly. Date: ______________________________________ First name: ______________________ Last name: ___________________________________ Address: _________________________________________ Apt # __________ City: ______________ _ Zip: _________ Home ph#: _______________ Cell ph#: _______________ Email address: _ ___________ ____ School: ______________________________________________________ Grade in Fall 2020: 10 11 12 What time does your school day end? __________ Please note: you must be able to get to the library by 3:30 p.m. to be hired Guidance counselor/ PIC / teacher contact at your school:______________________________________ Languages spoken: _________________________________________________________ Boston Public Library Mentor Application page 1 of 6 How did you hear about the Homework Help program at the BPL? □ At school □ At the Library □ Online □ A friend who is a mentor □ Other:______________________ Are you available to work at least two days per week for the entire school year, September through May? Yes / No Do you participate in sports? Yes / No During which months?__________________________ Homework Help is offered in most branches Monday-Thursday 3:30-5:30pm. Please rank your preference of work days, starting with 1= first choice, 2=second choice, etc. -

Interpretation

Interpretation Interpretation in Spanish is provided. WEST END BRANCH LIBRARY STUDY CITY OF BOSTON | BOSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY | ANN BEHA ARCHITECTS Zoom Protocol Questions will be answered at the end of the presentation. To speak please: Use the Q&A function at the bottom of the screen. Or use the raise hand function to be unmuted. If calling in by phone, dial *9 to raise your hand to be unmuted. WEST END BRANCH LIBRARY STUDY CITY OF BOSTON | BOSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY | ANN BEHA ARCHITECTS West End Branch Library Study Public Meeting October 22, 2020 Martin J. Walsh, Mayor Patrick Brophy, Chief of Operations Boston Public Library David Leonard, President City of Boston, Public Facilities Department Department of Neighborhood Development Sheila Dillion, Director AnnBehaArchitects WEST END BRANCH LIBRARY STUDY CITY OF BOSTON | BOSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY | ANN BEHA ARCHITECTS Agenda Welcome Introduction of Project Project Team Process and Schedule COB’s Housing With Public Assets Initiative Library Programming Recent BPL Branch Projects Base Branch Program Overview Example HWPA Projects Community Feedback Next Steps WEST END BRANCH LIBRARY STUDY CITY OF BOSTON | BOSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY | ANN BEHA ARCHITECTS Introduction of Project WEST END BRANCH LIBRARY STUDY CITY OF BOSTON | BOSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY | ANN BEHA ARCHITECTS PROJECT SCOPE • Evaluate existing building’s physical condition and its ability to meet programmatic needs and sustainable building systems. • Identification of neighborhood demographic trends. • Develop a building space program base on Boston Public Library’s improved library services and feedback from community. • Strengthen the library’s connection to the West End neighborhood and develop possible expanded program opportunities specific to that community. -

Free Tax Services

IF YOU WORKED IN 2018 & EARNED $55K OR LESS FREE TAX SERVICES JVS CENTER FOR ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITY 75 Federal Street, 3rd Floor, Boston MA 02110 JVS TAX SITE HOURS: TUESDAY & THURSDAY 4:00-8:00 PM JANUARY 29th - APRIL 11th Make your appointment on-line: https://freetaxhelp.us/-/jvs | 617.399.3235 Fast, easy, and free tax preparation IRS certified tax preparers that provide quality returns fast Maximize your refund, get all the credits you deserve EITC, child tax credits, health care tax credits Make the most of your refund Save for emergencies, build credit, and open a bank account https://freetaxhelp.us/-/jvs | 617.399.3235 fb.com/BostonTaxHelp @BosTaxHelp MAKE SURE TO BRING: ALLSTON/BRIGHTON CODMAN SQUARE QUINCY HEALTH CENTER F ABCD: ALLSTON 1199 SEIU Non-expired Photo ID 450 Washington Street required BRIGHTON NOC 108 Myrtle Street 640 Washington Street 617.825.9660 617-284-1199 F Social Security card or 617.903.3640 DOTHOUSE HEALTH Individual Taxpayer ID Letter ROXBURY ALLSTON BRIGHTON CHILD & 1353 Dorchester Avenue (ITIN) for you, your depen- 617.288.3230 ABCD: ROXBURY/ dents and/or your spouse FAMILY SERVICES CENTER NORTH DORCHESTER 406 Cambridge Street DOWNTOWN NEIGHBORHOOD F A copy of last year’s tax 855.687.7345 ABCD: ROBERT M. COARD OPPORTUNITY CENTER return [email protected] BUILDING 565 Warren Street 617.442.5900 F All 1099 forms: BRIGHTON BRANCH BOSTON 178 Tremont Street 617.348.6583 1099-G (unemployment), PUBLIC LIBRARY ROXBURY CENTER FOR 1099-R (pension payments), 40 Academy Hill Road JVS CENTER FOR FINANCIAL EMPOWERMENT 855.687.7345 -

The Art & Architecture of the Basilica of Saint Lawrence

Chapel of Our Lady Exterior Rafael Guastavino The Art & Architecture of The style, chosen by the architect, is Guastavino (1842-1908) an architect and builder of To the left of the main altar is the Chapel of Our Lady. Spanish origin, emigrated to the United States from The white marble statue depicts Our Lady of the Spanish Renaissance. The central figure Barcelona in 1881. There he The Basilica of Assumption, patterned after the famous painting by on the main facade is that of our patron, had been a successful Murillo. Inserted in the upper part of the altar is a faience the 3"I century archdeacon, St. The Guastavino architect and builder, D.M. entitled The Crucifixion, which is attributed to an old Lawrence, holding in one hand a palm system represents a Saint Lawrence, renowned pottery in Capo di Monte, Italy. On either side designing large factories and unique architectural A Roman Catholic Church frond and in the other a gridiron, the homes for the industrialists of the tabernacle are niches containing statues of the treatment that has instrument of his torture. On the left of of the region of Catalan. He following: from the extreme left, Sts. Margaret, Lucia, given America some Cecilia, Catherine of Alexandria, Barbara, Agnes, Agatha, St. Lawrence is the first martyr, St. was also credited there with and Rose of Lima. Framing the base of the altar is a series Stephen, holding a stone, the method of being responsible for the of its most of tiles with some titles his martyrdom. He also holds a palm. -

H. H. Richardson's House for Reverend Browne, Rediscovered

H. H. Richardson’s House for Reverend Browne, Rediscovered mark wright Wright & Robinson Architects Glen Ridge, New Jersey n 1882 Henry Hobson Richardson completed a mod- flowering, brief maturity, and dissemination as a new Amer- est shingled cottage in the town of Marion, overlook- ican vernacular. To abbreviate Scully’s formulation, the Iing Sippican Harbor on the southern coast of Shingle Style was a fusion of imported strains of the Eng- Massachusetts (Figure 1). Even though he had only seen it lish Queen Anne and Old English movements with a con- in a sadly diminished, altered state and shrouded in vines, in current revival of interest in the seventeenth-century 1936 historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock would neverthe- colonial building tradition in wood shingles, a tradition that less proclaim, on the walls of the Museum of Modern Art survived at that time in humble construction up and down (MoMA) in New York, that the structure was “perhaps the the New England seaboard. The Queen Anne and Old most successful house ever inspired by the Colonial vernac- English were both characterized by picturesque massing, ular.”1 The alterations made shortly after the death of its the elision of the distinction between roof and wall through first owner in 1901 obscured the exceptional qualities that the use of terra-cotta “Kent tile” shingles on both, the lib- marked the house as one of Richardson’s most thoughtful eral use of glass, and dynamic planning that engaged func- works; they also caused it to be misunderstood—in some tionally complex houses with their landscapes. -

Structural Assessment of the Guastavino Masonry Dome of the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine

Structural Assessment of the Guastavino Masonry Dome of the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine by Hussam Dugum Bachelor of Engineering in Civil Engineering and Applied Mechanics McGill University, Montreal, 2012 Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Engineering in Civil and Environmental Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2013 c 2013 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Signature of the Author: Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering May 10, 2013 Certified by: John A. Ochsendorf Professor of Building Technology and Civil and Environmental Engineering Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Heidi M. Nepf Chair, Departmental Committee for Graduate Students Structural Assessment of the Guastavino Masonry Dome of the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine by Hussam Dugum Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering on May 10, 2013 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Engineering in Civil and Environmental Engineering Abstract Historic masonry structures have survived many centuries so far, yet there is a need to better understand their history and structural safety. This thesis applies structural analysis techniques to assess the Guastavino masonry dome of the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine. This dome is incredibly thin with a L/t ratio of 200. Thus, it is important to assess this dome and its supporting arches, and confirm they are within adequate safety limits. This thesis gives an overview of the basic principles of masonry structural analysis methods, including equilibrium and elastic methods. Equilibrium methods are well suited to assess masonry structures as their stability is typically a matter of geometry and equilibrium rather than material strength. -

Boston Public Library FY17 Q1 Usage by Location July, August, September 2016

Boston Public Library FY17 Q1 Usage by Location July, August, September 2016 Computer Wireless Location Visitors Location Circulation Location Programs Attendance Location Sessions Location Sessions Reach Central Library 541,208 Central Library 251,225 Central Library 558 21,650 Central Library 55,687 Central Library 93,020 941,698 Digital Borrowing 397,543 397,543 Adams St. 17,507 Adams St. 27,573 Adams St. 78 1,756 Adams St. 2,347 Adams St. 774 48,279 Brighton 19,683 Brighton 36,655 Brighton 35 1,156 Brighton 2,911 Brighton 1,763 61,047 Charlestown 19,331 Charlestown 23,049 Charlestown 87 1,956 Charlestown 1,824 Charlestown 1,356 45,647 Codman Sq. 25,011 Codman Sq. 18,724 Codman Sq. 110 2,422 Codman Sq. 4,796 Codman Sq. 1,391 50,032 Connolly 23,690 Connolly 47,761 Connolly 73 1,446 Connolly 1,838 Connolly 1,933 75,295 Dudley 30,379 Dudley 18,673 Dudley 134 786 Dudley 5,487 Dudley 6,046 60,719 East Boston 38,553 East Boston 54,116 East Boston 105 2,031 East Boston 10,484 East Boston 3,492 106,750 Egleston 13,141 Egleston 17,037 Egleston 72 1,095 Egleston 3,078 Egleston 860 34,188 Faneuil 15,754 Faneuil 25,363 Faneuil 63 994 Faneuil 1,366 Faneuil 910 43,456 Fields Corner 23,134 Fields Corner 26,949 Fields Corner 76 1,040 Fields Corner 4,243 Fields Corner 2,018 56,420 Grove Hall 25,064 Grove Hall 20,133 Grove Hall 202 2,786 Grove Hall 6,643 Grove Hall 1,875 53,917 Honan-Allston 15,436 Honan-Allston 19,616 Honan-Allston 181 2,220 Honan-Allston 2,635 Honan-Allston 2,406 40,274 Hyde Park 27,038 Hyde Park 28,984 Hyde Park 193 4,010 Hyde Park -

The Rhode Island State House

THE RHODE ISLAND STATE HOUSE: The Competition (1890-1892) by Hilary A. Lewis Bachelor of Arts Princeton University Princeton, New Jersey 1984 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY FEBRUARY 1988 (c) Hilary A. Lewis 1988 The Author hereby grants to M.I.T. permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. .Signature of author Hilary A. Lewis artment of Architecture January 15, 1988 Certified by Sta ford Anderson Professor of Architecture Thesis Supervisor Accepted by 'Julian Beinart Chairman Departmental Committee for Graduate Students OF E-THNOLOGY UBMan Rot' CONTENTS A. Contents......... .............................. .1 B. Acknowledgements. ............. ................. .2 C. Abstract......... ...............................3 I. Introduction....................................4 II. Body of the Text: The Beginnings of the Commission.... ........... 8 The Selection of McKim, Mead & White .......... 23 Following the Competition........... .......... 39 III. Conclusion.....................................44 IV. Appendices "A" The Conditions for the Competition. ....... 47 "B" Statements of the Governors........ ....... 57 Letters................................. ....... 79 McKim and Burnham...................... ...... 102 The City Plan Commission Report........ 105 Illustrations of Competing Designs..... ...... 110 V. Bibliography............................ ...... 117 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis was written under the direction of Professor Neil Levine, Chairman of the Fine Arts Department at Harvard University. Professor Levine has not only been extremely helpful with this project; he has been a wonderful teacher who has a gift for instilling his love of the subject in others. I thank him for all of his guidance. H.A.L. Cambridge 2 THE RHODE ISLAND STATE HOUSE: The Competition (1890-1892) by Hilary A. -

Pamela Carver, Clerk of the Board 1 TRUSTEES

TRUSTEES OF THE PUBLIC LIBRARY OF THE CITY OF BOSTON Meeting of the Trustees as a Corporation and Administrative Agency Thursday, March 8, 2018, 5:00 p.m. Boston Public Library, Roslindale Branch 4246 Washington Street, Roslindale, MA 02131 DRAFT MINUTES A Meeting of the Trustees of the Public Library of the City of Boston was held at the Roslindale Branch Library, 4246 Washington Street, Roslindale, MA 02131 on Thursday, March 8, 2018 at 5:00 p.m. Present at the meeting were: Chair, Bob Gallery, Vice-Chair, Evelyn Arana-Ortiz and Trustees: Zamawa Arenas, Cheryl Cronin, Priscilla Douglas, John Hailer, Paul LaCamera, and Representative Byron Rushing. Trustees Ben Bradlee and Priscilla Douglas were not present. Also attending were David Leonard, President, Justin Sterritt, City Budget Director, and Pamela Carver, Clerk of the Board. Several BPL staff and members of the public were also present. Chair Robert Gallery called the meeting to order at 5:01 p.m. and addressed the order of business. Mr. Gallery thanked everyone for attending the meeting and invited Roslindale Branch Librarian, Becky Manos to give welcome remarks. Ms. Manos thanked the Board and President Leonard and introduced her staff. She thanked everyone for coming and expressed her gratitude for Mayor Walsh, Councilor Tim McCarthy, and all of the Friends for their ongoing support. She and her staff are very excited for the branch renovation. She mentioned there was an influx of young families and there has been an added interest in the Roslindale Branch. They are excited to serve the changing needs of the community. -

Guastavino Structural Tile Vaulting in Pittsburgh Spring Semester 2021

The Osher Lifelong Learning Institute University of Pittsburgh, College of General Studies Guastavino Structural Tile Vaulting in Pittsburgh Spring Semester 2021 Instructor: Matthew Schlueb Program Format: Five week course, 90 minute academic lectures and guided tour, with time for questions. Course Objective: To offer a master level survey of the Pittsburgh architectural works by Rafael Guastavino and his son, drawn from their Catalan traditions in masonry vaulting, as interpreted by a practicing architect and author of architecture. Course Description: Architect Rafael Guastavino and his son Rafael Jr. emigrated to the United States in 1881, bringing the traditional construction method of structural tile vaulting from their Catalan homeland, thereby transforming the architectural landscape from Boston to San Francisco. This course will examine their works in Pittsburgh, illustrating the vaults and domes made with structural tiles, innovations in thin shell construction, fire-proofing, metal reinforcing, herringbone patterns, skylighting, acoustical and polychromatic tiles. Lectures supplemented with a guided tour of these local structures, provided logistics and health safety measures permit. Course Outline: Lecture 1: From Valencia to New York [Tuesday, March 16, 2021 3pm-4:30pm] Convent of Santo Domingo Refectory (arches and vaults; Mudéjar style; Zaragoza, Spain; 1283) Monastery of Santo Domingo Refectory (bóveda tabicadas / maó de pla; Juan Franch; Valencia, Spain; 1382) Batlló Textile Factory (vaulted arcade atop metal columns; Rafael Guastavino; Barcelona, Spain; 1868) La Massa Theater (shallow dome vault; Rafael Guastavino; Vilassar de Dalt, Spain; 1880) Boston Public Library (structural tile vaults; Charles McKim; Boston, Massachusetts; 1889-1895) St. Paul’s Chapel (dome; Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes; Columbia University, New York; 1907) Lecture 2: Material Innovations in Building Science [Tuesday, March 23, 2021 3pm-4:30pm] Cathedral of St. -

RAFAEL GUASTAVINO MORENO Inventiveness in 19Th Century Architecture by Jaume Rosell Colomina

RAFAEL GUASTAVINO MORENO Inventiveness in 19th century architecture by Jaume Rosell Colomina This article was published in Catalan in pa. 494-522 by CAMARASA, Josep M.; ROCA, Antoni (dir.): Ciència i Tècnica als Països Catalans : una aproximació biogràfica (2v). Fundació Catalana per a la Recerca. Barcelona, 1995. The English version, revised by the author, was translated by Edward Krasny. An English version of this text was published in pp. 45-49 by TARRAGÓ, Salvador (editor): Guastavino Co. (1885-1962) : Catalogue of works in Catalonia and America. Col·legi d'Arquitectes de Catalunya. Barcelona, 2002. (ISBN 84-88258-65-8). Revised version, January 2010. Catalan and Spanish version in: https://upcommons.upc.edu/e-prints/browse?type=author&value=Rosell%2C+Jaume In memory of my father, Pere Rosell i Millach RAFAEL GUASTAVINO MORENO València, 1842 – Black Mountains, North Carolina, 1908 Key words: architecture, industrial architecture, cement, construction, cohesive construction, iron, brick, flat brick masonry, master builders, Modernisme, fire resistance, vaults. The contribution of Valencian Rafael Guastavino Moreno to Architecture was especially important in the technical area. He was the leading moderniser of an ancient building technique using flat brick masonry techniques, above all to erect vaults. Guastavino would later transfer these techniques from Catalonia to the United States of America, where he founded a family company that built, over two generations, more than one thousand buildings, many of them of great importance. These two accomplishments represent a notable contribution to contemporary Architecture: more so if we take into account a series of technological reflections and proposals that also constitute a contribution to the modernisation of construction, insofar as they entail an effort to understand the behaviour of and ways in which the new materials worked. -

Newport, Rhode Island As Ward Mcallister Found It

“The Glare and Glitter of that Fashionable Resort”: Newport, Rhode Island as Ward McAllister Found It By Emily Parrow A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Liberty University Lynchburg, Virginia April 2021 ‘THE GLARE AND GLITTER OF THAT FASHIONABLE RESORT’: NEWPORT, RHODE ISLAND AS WARD MCALLISTER FOUND IT by Emily Parrow Liberty University APPROVED BY: David Snead, Ph.D., Committee Chair Michael Davis, Ph.D., Committee Member Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1: The Southern Connection ............................................................................................17 Chapter 2: The European Connection ............................................................................................43 Chapter 3: The New York Connection and the Era of Formality ..................................................69 Chapter 4: The New York Connection and the Era of Frivolity ..................................................93 Conclusion ..................................................................................................................................130 1 Introduction “Who the devil is Ward McAllister?” The New York Sun posed to its readers in 1889, echoing “a question that has been asked more times of late than any other by reading men all over the country and even in this city.”1 The journalist observed, “In the