As You Like It

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Masculinity and Effeminacy in Early Modern Drama

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Dissertations 2020 “THE SKIPPING KING”: MASCULINITY AND EFFEMINACY IN EARLY MODERN DRAMA Danielle Johanna Sanfilippo University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss Recommended Citation Sanfilippo, Danielle Johanna, “THE" SKIPPING KING”: MASCULINITY AND EFFEMINACY IN EARLY MODERN DRAMA" (2020). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 1166. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/1166 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THE SKIPPING KING”: MASCULINITY AND EFFEMINACY IN EARLY MODERN DRAMA BY DANIELLE JOHANNA SANFILIPPO A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2020 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DISSERTATION OF DANIELLE JOHANNA SANFILIPPO APPROVED: Dissertation Committee: Major Professor Travis Williams Jean Walton Rachel Walshe Nasser H. Zawia DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2020 Abstract This dissertation analyzes depictions of effeminacy and anxiety surrounding masculinity in early modern drama. Effeminacy is a frequently used term in the literature of the period, occurring seven times in Shakespeare alone. For my research, I combine literary analysis and performance criticism. I consulted the National Theatre Archives in London and the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust in Stratford to analyze performances of early modern plays. Effeminacy is a wide-reaching mode of being that makes several layers of meaning. For royals and men of rank, the presumption of effeminacy is a danger to the realm. -

2016 Study Guide 2016 Study Guide

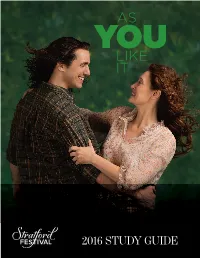

2016 STUDY GUIDE 2016 STUDY GUIDE EDUCATION PROGRAM PARTNER AS YOU LIKE IT BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE DIRECTOR JILLIAN KEILEY TOOLS FOR TEACHERS sponsored by PRODUCTION SUPPORT is generously provided by M. Fainer and by The Harkins/Manning Families In Memory of James & Susan Harkins INDIVIDUAL THEATRE SPONSORS Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 season of the Festival season of the Avon season of the Tom season of the Studio Theatre is generously Theatre is generously Patterson Theatre is Theatre is generously provided by provided by the generously provided by provided by Claire & Daniel Birmingham family Richard Rooney & Sandra & Jim Pitblado Bernstein Laura Dinner CORPORATE THEATRE PARTNER Sponsor for the 2016 season of the Tom Patterson Theatre Cover: Cyrus Lane, Petrina Bromley. Photography by Don Dixon. Table of Contents The Place The Stratford Festival Story ........................................................................................ 1 The Play The Playwright: William Shakespeare ........................................................................ 3 A Shakespearean Timeline ......................................................................................... 4 Plot Synopsis ............................................................................................................... 6 Cast of Characters ...................................................................................................... 7 Sources, Origins and Production History .................................................................. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

-

English Productions of Measure for Measure on Stage and Screen

English Productions of Measure for Measure on Stage and Screen: The Play’s Indeterminacy and the Authority of Performance Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Department of English and Creative Writing Lancaster University March, 2016 Rachod Nusen Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work, and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere. Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my supervisor, Professor Alison Findlay. Without her advice, kindness and patience, I would be completely lost. It is magical how she could help a man who knew so little about Shakespeare in performance to complete this thesis. I am forever indebted to her. I am also indebted to Dr. Liz Oakley-Brown, Professor Geraldine Harris, Dr. Karen Juers-Munby, Dr. Kamilla Elliott, Professor Hilary Hinds and Professor Stuart Hampton-Reeves for their helpful suggestions during the annual, upgrade, mock viva and viva panels. I would like to acknowledge the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive, the National Theatre Archive, the Shakespeare’s Globe Library and Archives, the Theatre Collection at the University of Bristol, the National Art Library and the Folger Shakespeare Library on where many of my materials are based. Moreover, I am extremely grateful to Mr. Phil Willmott who gave me an opportunity to interview him. I also would like to take this opportunity to show my appreciation to Thailand’s Office of the Higher Education Commission for finically supporting my study and Chiang Mai Rajabhat University for allowing me to pursue it. -

Foxtel Arts Celebrates William Shakespeare's 400

Media release: Friday April 1, 2016 FOXTEL ARTS CELEBRATES WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE’S 400 YEAR LEGACY IN APRIL Foxtel Arts, Foxtel’s High Definition dedicated arts channel commemorates the prolific playwright William Shakespeare throughout the month of April dedicating its programming to the extraordinary world and works of The Bard and their still vivid impact today, 400 years after his death. Foxtel Arts continues to bring extraordinary experiences in Australian arts and the world’s finest performing artists from the greatest opera houses, concert halls and festival stages and, this month, the channel celebrates the legacy of Shakespeare with 16 live recorded performances of Shakespeare’s best works from the iconic Globe Theatre, London airing Sunday to Wednesday evenings at 8.30pm throughout April. Foxtel Arts’ presenter Leo Schofield hosts all 16 Shakespeare Globe Theatre performances from this Sunday April 3 featuring a raft of Royal Shakespeare Company alumni and showcasing the best of Shakespeare's comedies, tragedies and historical plays including Romeo and Juliet, Macbeth, Love Labour's Lost, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Othello and Twelfth Night featuring an all-male cast including Stephen Fry as Malvolio, Sunday April 10 at 8.30pm. Shakespeare Uncovered, an extraordinary six-part documentary series combines new analysis of some of Shakespeare’s most famous works with the personal passion of the actors who have starred in them. Interviews with directors, actors and scholars are combined with clips from some of the most celebrated productions to offer a captivating insight for both those new to Shakespeare and those familiar with his plays. The series also features clips from some of the most celebrated productions and excerpts from the plays especially rehearsed and performed at Shakespeare’s Globe. -

37 Plays 37 Films 37 Screens

the complete walk 37 PLAYS 37 FILMS 37 SCREENS A celebratory journey through Shakespeare’s plays along the South Bank and Bankside Credits and Synopses shakespearesglobe.com/400 #TheCompleteWalk 1 contents 1 THE TWO GENTLEMEN OF VERONA 3 20 HENRY V 12 2 HENRY VI, PART 3 3 21 AS YOU LIKE IT 13 3 THE TAMING OF THE SHREW 4 22 JULIUS CAESAR 13 4 HENRY VI, PART 4 23 OTHELLO 14 5 TITUS ANDRONICUS 5 24 MEASURE FOR MEASURE 14 6 HENRY VI, PART 2 5 25 TWELFTH NIGHT 15 7 ROMEO & JULIET 6 26 TROILUS AND CRESSIDA 15 8 RICHARD III 6 27 ALL’S WELL THAT ENDS WELL 16 9 LOVE’S LABOUR’S LOST 7 28 TIMON OF ATHENS 16 10 KING JOHN 7 29 ANTONY AND CLEOPATRA 17 11 THE COMEDY OF ERRORS 8 30 KING LEAR 17 12 RICHARD II 8 31 MACBETH 18 13 A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM 9 32 CORIOLANUS 18 14 THE MERCHANT OF VENICE 9 33 HENRY VIII 19 15 HENRY IV, PART 1 10 34 PERICLES 19 16 MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING 10 35 CYMBELINE 20 17 HENRY IV, PART 2 11 36 THE WINTER’S TALE 20 18 THE MERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR 11 37 THE TEMPEST 21 19 HAMLET 12 2 THE TWO GENTLEMEN HENRY VI, PART 3 OF VERONA Filmed at Towton Battlefield, England Filmed at Scaligero Di Torri Del Benaco, St Thomas’ Hospital Garden Verona, Italy St Thomas’ Hospital Garden CREDITS Father DAVID BURKE CREDITS Son TOM BURKE Julia TAMARA LAWRANCE Henry VI ALEX WALDMANN Lucetta MEERA SYAL Director NICK BAGNALL Director of Photography ALISTAIR LITTLE Director CHRISTOPHER HAYDON Sound Recordist WILL DAVIES Director of Photography IONA FIROUZABADI Sound Recordist JUAN MONTOTO UGARTE ON-STAGE PRODUCTION (GLOBE TO GLOBE FESTIVAL) ON-STAGE PRODUCTION Performed in Macedonian by the National Theatre (GLOBE ON SCREEN) of Bitola, Macedonia A Midsummer Night’s Dream Twelfth Night Director JOHN BLONDELL As You Like It Othello SYNOPSIS Romeo and Juliet As the War of the Roses rages, Richard, Duke of Measure for Measure York, promises King Henry to end his rebellion if his All’s Well That Ends Well sons are named heirs to the throne. -

The Footprints Festival We Are Reopening with a Celebration of Theatre and the People Who Make It

Live on stage. Enjoy from home or at our theatre. 17 May - 1 August 2021 Drama Solo Cabaret Classics Showcases Poetry FESTIVAL Welcome to the Footprints Festival We are reopening with a celebration of theatre and the people who make it. Over 40 productions feature in the Footprints Festival, encompassing drama, music, poetry, and comedy; shows to make us laugh, think, and perhaps shed a tear or two. If, like us, you can’t wait to be back in the unique atmosphere of our theatre, our doors are open! We will take every precaution to keep you safe from the moment you enter the building and come downstairs. Social distancing means our maximum audience size is 25 - so book early. But if you prefer to watch from home, we’ll be live-streaming every single event of the Footprints Festival so you can watch on your computer or television. The Footprints Festival has six strands: Drama, Solo, Cabaret, Classics, Poetry and Showcases. Three fabulous plays are at its heart: Two Horsemen, Lone Flyer and Mr and Mrs Nobody. With a Festival Pass, tickets are cheaper than ever before. The Footprints Festival features too many great actors, writers and directors to list here - but as always at Jermyn Street Theatre, household names share the bill with exciting newcomers. Come to see the people you’ve missed, and discover the stars of tomorrow. Whether you join us in our theatre, or from your home, we’re To book, visit jermynstreettheatre.co.uk overjoyed to welcome you back. Or call the Box Office 020 7287 2875 Tom Littler and Penny Horner Artistic and Executive Directors Live on stage. -

National Theatre

National Theatre Annual ReportAnnual 2013–2014 Annual Report 2013–2014 Annual Report For the 52 weeks ended 30 March 2014 2 Board and Advisers 4 Purpose, Vision and Objectives 6 John Makinson, Chairman 8 Nicholas Hytner, Director 12 Nick Starr, Executive Director 15 The National Theatre on tour 16 Plays and Artists 21 National Theatre Productions 25 Awards 26 National Theatre 50th Anniversary celebrations 30 Audiences 33 National Theatre Live, Digital Innovation and Broadcast 37 Learning 40 Public Engagement 42 National Theatre Future 44 NT Studio 46 Leadership 48 Finance and Sustainability 55 Fundraising 56 Supporters 64 Performers 68 NT Associates, Committee Membership and Heads of Departments 69 Photo captions In this document, The Royal National Theatre is referred to as If you would like to receive it in large print, “the NT”, “the National”, and “the National Theatre”. or you are visually impaired and would The full Financial Review and Financial Statements (and this like a member of staff to talk through the Annual Report) are available to download at www.nationaltheatre. org.uk/annualreport The Trustees’ Report comprises those items publication with you, please contact the on pages 2 – 5 and12 – 69 of the Annual Report and pages Board Secretary at the National Theatre. 1 – 20 of the Financial Statements. National Theatre Annual Report 2013–2014 1 Board and Advisers Board Members Executive Chairman John Makinson Director* Peter Bennett-Jones Nicholas Hytner Dame Ursula Brennan DCB Executive Director Dominic Casserley Nick Starr -

NT Annual Report 0405 0.Pdf

The Royal National Theatre Annual Report & South Bank, London SE1 9PX Financial Statements + 44 (0)20 7452 3333 For the 53 weeks ended 3 April 2005 www.nationaltheatre.org.uk 2 Aims and Objectives 3 Nicholas Hytner, Artistic Director Company registration number 749504 4 Sir Hayden Phillips, Chairman Registered charity number 224223 5 Overview of 2004-05 & Future Plans Registered office Upper Ground, 8 The Year in Photographs I London SE1 9PX 12 Studio Board 13 Education & Training Chairman Sir Hayden Phillips GCB 14 Productions Opening in 2004-05 Anjali Arya Susan Chinn 16 Touring, Transfers & Awards Nicola Horlick 17 Acting company Rachel Lomax 18 Musicians & Watch This Space Caragh Merrick Grahame Morris 19 Platforms, Exhibitions & Publications Caro Newling 20 Archive, Website & Access Ben Okri OBE 21 Development & Fundraising André Ptaszynski Rt Hon Lord Smith of Finsbury 22 Development Supporters Edward Walker-Arnott 25 Personnel Nicholas Wright 28 The Year in Photographs II Company Secretary Menna McGregor 32 Structure, Governance & Management Executive 36 Financial Review Artistic Director Nicholas Hytner Executive Director Nick Starr 40 Report of the Board General Manager Maggie Whitlum 41 Independent Auditors' Report Finance Director Lisa Burger 42 Financial Statements and Notes Associate Directors 58 Associates & Committees Howard Davies Tom Morris Bankers Coutts & Co 440 Strand, London WC2R 0QS Auditors PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP This Annual Report & Financial 1 Embankment Place, London WC2N 6RH Statements is available to download at www.nationaltheatre.org.uk If you would like to receive it in large print, or you are a visually-impaired person and would like a member of staff to talk through the publication with you, please contact the Company Secretary at the National Theatre.