1 Bruce's Beach Report from the History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legislative, Public Affairs and Media Report

BOARD MEETING DATE: November 2, 2018 AGENDA NO. 14 REPORT: Legislative, Public Affairs and Media Report SYNOPSIS: This report highlights the September 2018 outreach activities of the Legislative, Public Affairs and Media Office, which includes: Major Events, Community Events/Public Meetings, Environmental Justice Update, Speakers Bureau/Visitor Services, Communications Center, Public Information Center, Business Assistance, Media Relations, and Outreach to Community Groups and Federal, State, and Local Government. COMMITTEE: No Committee Review RECOMMENDED ACTION: Receive and file. Wayne Nastri Executive Officer DJA:LTO:DM:jns BACKGROUND This report summarizes the activities of the Legislative, Public Affairs and Media Office for September 2018. The report includes: Major Events, Community Events/Public Meetings; Environmental Justice Update; Speakers Bureau/Visitor Services; Communications Center, Public Information Center; Business Assistance; Media Relations; and Outreach to Community Groups and Governments. MAJOR EVENTS (HOSTED AND SPONSORED) Each year SCAQMD staff engage in holding and sponsoring a number of major events throughout the SCAQMD’s four county area to promote, educate and provide important information to the public regarding reducing air pollution, protecting public health, and improving the air quality and the economy. September 12 SCAQMD hosted the “Seniors Celebrating Healthy Living & Clean Air Fair” at the Riverside Convention Center. The event provided information on SCAQMD, air quality issues and health. The event was attended by more than 350 seniors from the Inland Empire. September 26 Staff organized the Fourth Annual Environmental Justice Community Partnership Conference entitled “Technology’s Role in the Future of Environmental Justice” at the Huffington Center at the St. Sophia Cathedral in Los Angeles. -

2018 California Journalism Awards — Print Contest Finalists

2018 California Journalism Awards — Print Contest Finalists Category Division Publication Entry Title Credits General Excellence Dailies: 50,001 & over Los Angeles Times 2/10/2018 & 2/11/2018 Los Angeles Times Staff General Excellence Dailies: 50,001 & over San Francisco Chronicle 9/23/2018 & 9/24/2018 San Francisco Chronicle Staff General Excellence Dailies: 50,001 & over The Mercury News/East Bay Times 9/2/2018 & 9/3/2018 The Mercury News Staff General Excellence Dailies: 50,001 & over The Sacramento Bee 9/2/2018 & 9/3/2018 Sacramento Bee Staff General Excellence Dailies: 50,001 & over The San Diego Union-Tribune 9/2/2018 & 9/3/2018 Union-Tribune Staff General Excellence Dailies: 15,001 - 50,000 Chico Enterprise-Record 2/10/2018 & 2/11/2018 Chico Enterprise-Record Staff General Excellence Dailies: 15,001 - 50,000 Marin Independent Journal 2/24/2018 & 2/25/2018 Marin Independent Journal Staff General Excellence Dailies: 15,001 - 50,000 The Bakersfield Californian 2/22/2018 & 2/23/2018 The Bakersfield Californian General Excellence Dailies: 15,001 - 50,000 The Modesto Bee 2/25/2018 & 2/26/2018 Modesto Bee Staff General Excellence Dailies: 15,001 - 50,000 The Press Democrat 9/29/2018 & 9/30/2018 Press Democrat Staff General Excellence Dailies: 15,000 & under Napa Valley Register 2/4/2018 & 2/5/2018 Napa Valley Register Staff General Excellence Dailies: 15,000 & under Santa Maria Times 2/1/2018 & 2/2/2018 Santa Maria Times Staff General Excellence Dailies: 15,000 & under The Record 9/12/2018 & 9/13/2018 The Record Staff General Excellence Dailies: 15,000 -

UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Leisure’s Race, Power and Place: The Recreation and Remembrance of African Americans in the California Dream Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0cm2m7vs Author Jefferson, Alison Rose Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA BARBARA Leisure’s Race, Power and Place: The Recreation and Remembrance of African Americans in the California Dream A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Alison Rose Jefferson Committee in charge: Professor Randy Bergstrom, Chair Professor Emeritus Douglas Daniels Professor Mary Hancock Professor George Lipsitz December 2015 The dissertation of Alison Rose Jefferson is approved. ____________________________________________ Douglas Daniels ____________________________________________ Mary Hancock ____________________________________________ George Lipsitz ____________________________________________ Randy Bergstrom, Committee Chair December 2015 Leisure’s Race, Power and Place: The Recreation and Remembrance of African Americans in the California Dream Copyright © 2015 by Alison Rose Jefferson iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to thank everyone who helped me over the years to uncover the research, which formed the bases of this dissertation. I especially want thank all my professors and colleagues who supported and/or guided me in the -

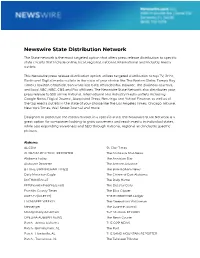

US State Distribution Network

Newswire State Distribution Network The State network is the most targeted option that offers press release distribution to specific state circuits that include online, local, regional, national, international and industry media outlets. This Newswire press release distribution option utilizes targeted distribution to top TV, Print, Radio and Digital media outlets in the state of your choice like The Boston Globe, Tampa Bay Times, Houston Chronicle, San Francisco Gate, Philadelphia Inquirer, The Business Journals, and local ABC, NBC, CBS and Fox affiliates. The Newswire State Network also distributes your press release to 550 online national, international and industry media outlets including Google News, Digital Journal, Associated Press, Benzinga and Yahoo! Finance, as well as all the top media outlets in the state of your choice like the Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, New York Times, Wall Street Journal and more. Designed to penetrate the media market in a specific state, the Newswire State Network is a great option for companies looking to grow awareness and reach media in individual states, while also expanding awareness and SEO through national, regional and industry specific pickups. Alabama AL.COM St. Clair Times ALABAMA POLITICAL REPORTER The Andalusia Star-News Alabama Today The Anniston Star Alabaster Reporter The Atmore Advance BT (THE BIRMINGHAM TIMES) The Birmingham News Daily Mountain Eagle The Citizen of East Alabama DOTHAN EAGLE The Daily Home FFP(FranklinFreePress.net) The Decatur Daily Franklin County Times The Elba -

A Survey on Recreational and Subsistence Fishing in Southern California Coastal Waters

A SURVEY ON RECREATIONAL AND SUBSISTENCE FISHING IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA COASTAL WATERS Prepared For: The Natural Resource Trusteesl Environmental Protection Agency 501 West Ocean Blvd. Long Beach, Ca 90802 United States Environmental Protection Agency Region 9 Superfund Division 75 Hawthorne Street San Francisco, CA 94105 Prepared By: CIC Research, Inc. 8361 Vickers Street San Diego, Ca 92111 Stratus Consulting, Inc. 1881 Ninth Street, Suite 201 Boulder, Co 80302 June,2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................................1 SITE BACKGROUND .......................................................................................................1 EXISTING FISHING STUDIES AND FISH CONSUMPTION ADVISORIES IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA. ...................................................................................3 PURPOSE AND OBJECTiVES .........................................................................................4 SURVEY IMPLEMENTATION AND DESIGN ...............................................................................6 OVERALL APPROACH ....................................................................................................6 QUESTIONNAIRE DESiGN ..............................................................................................6 SAMPLING DESIGN .........................................................................................................9 Use of MRFSS Data ..............................................................................................9 -

California Media Outlets

California Media Outlets Newswire’s Media Database provides targeted media outreach opportunities to key trade journals, publications, and outlets. The following records are related to traditional media from radio, print and television based on the information provided by the media. Note: The listings may be subject to change based on the latest data. ________________________________________________________________________________ Radio Stations 28. Fresh Air - NPR 29. FULL CIRCLE - KPFA-FM 1. A Way With Words 30. GOOD MORNING LA 2. American RadioWorks 31. Griffin Radio 3. an organic conversation 32. iHeartMedia, Inc. 4. Animal Radio 33. John Tesh Radio Show 5. ANNENBERG RADIO NEWS 34. K-Dawg 6. APEX Express 35. K201HR-FM 7. Armstrong & Getty Show 36. K218EN-FM 8. BAJABA JazzLine 37. K277BN-FM 9. Baka Boyz Hip Hop Master Mix 38. KABC-AM [TalkRadio 790 KABC] 10. Bay Area Third Eye 39. KAD94-FM 11. Bay Native Circle 40. KADA-AM [The Ref] 12. Benztown Radio Networks 41. KAKX-FM 13. Breakfast with the Beatles 42. KALW-FM 14. Brian Sussman Encore 43. KALX-FM 15. BUSINESS ROCKSTARS 44. KAPU Radio 16. Chris Daniel Show 45. KATA-AM [ESPN Radio] 17. Coast to Coast AM 46. KATJ-FM [Kat Country 100.7] 18. Con Sabor 47. KAZU-FM 19. El Despertador 48. KBAY-FM [K-BAY] 20. El Show de Piolín 49. KBBL-FM [106.3 The Bull] 21. En Las Noches 50. KBEE-FM [B98.7] 22. ESPN Radio 51. KBHR-FM [K-BEAR "The Bear is 23. Excelsior German Radio Show Everywhere"] 24. Experience Talks 52. KBMG-FM [Latino] 25. -

Director Deane Dana's Letter Regarding Promotion of the Green

November 2, 1995 Anseles Coumy ~le~ropolflan Transportation TO: MTA BOARD OF DIRECTORS Authority FROM: 8~8 West Seventh Street J ~@REW Suite 300 SUBJECT: DI~R DEANE DANA’S LETTER REGARDING Los Angeles, CA9oo~ 7 PROMOTION OF THE GREEN LINE 21~.972.6ooo Mailing Address: Attached is a copy of the response to Director Dana’s inquiry on Green Line promotion. IP+O Box i9, Los Angeles CA 9005} If you should have any questions, please contact Barry Engelberg at (21 3) 244-7408. October 30, 1995 Tt~e Honorable Deane Dar~a Supervisor, Fourth District Los An_~eles County County of Los Angeles Hetropolitan Hall of Administration Transportation 500 West Temple Street, Room 822 Authority Los Angeles, CA 90012 818 West Seventh Street Dear Su~ Suite 300 Thank you for your letter of September 14, 1995 regarding the 7Los Angeles, CA 9ool promotion of the Green Line. I respect your concern about this matter. 21~ ()72 (~ooo I believe we have provided a large volume of accurate public Mailing Address: information about the line, and this effort has undoubtedly contributed to the higher-than-predicted ridership figures you cited. Los ?, ~g~ les, CA9oo53 Prior to or shortly after the official opening, the public has been furnished with: ¯ Timetables ¯ Fact Sheets ¯ Question and Answer Flyers ¯ Fun Maps showing major destinations, employment centers and connection to the Blue Line ¯ Brochures showing MTA bus service changes with routes serving the Metro Green Line stations In the first two months of operation, we distributed approximately 200,000 rail and bus timetables, fact sheets and other Green Line materials at community events alone. -

Alabama Media Directory

Alabama Media Directory Alabama Newswire ABC 33/40 News ALMetro360 Advertiser Gleam Alabama Gazette Homepage Alabama Media Group Alabama Messenger Alabama News Network Alabama PolitiCal Reporter Alabama PubliC Radio Alabama State News Alabaster Reporter Andalusia Star News Atmore News Birmingham Business Journal Birmingham Magazine CBS 42 CNHI Cherokee County Herald Chilton County News ChoCtaw Sun AdvoCate Clarke County DemoCrat Courier Journal Daily Mountain Eagle Demopolis Times Dothan Eagle FOX10 News Franklin County Times Franklin Free Press Gadsden Messenger Gadsden Times Greenville Standard Gulf Coast Media Hartselle Enquirer Hoover Sun Huntsville News Jackson County Sentinel Journal ReCord Lagniappe Latino News Lowndes Signal Madison ReCord Montgomery Advertiser Moundville Times Mountain Valley News Mullet Wrapper NBC 15 NewsVerified acCount News Radio 105.5 WERC North Chilton Advertiser North Jefferson News Northwest Alabamian Opelika Auburn News Opelika Observer Orange Beach News Over the Mountain Journal PiCkens County Herald Planet Weekly Shelby County Reporter Shelby County Reporter Shoals Insider Southern Jewish Life Speakin Out News St. Clair News Aegis Talk 99.5 The Alabama Baptist The Alexander City Outlook The Anniston Star The Arab Tribune The Atmore AdvanCe The Auburn Plainsman The Auburn Villager The Aumnibus The Birmingham Free Press The Blount Countian The Brewton Standard The Call News The ChantiCleer The Clanton Advertiser The Clarion The Corner News The Crimson White The Cullman Times The Cullman Tribune The DeCatur -

JOUR 206: Reporting and Writing Practicum (Community Reporting) 1 Unit

JOUR 206: Reporting and Writing Practicum (Community Reporting) 1 Unit Spring 2021 – Tuesdays 8-11:50 a.m./11 a.m.-2:50 p.m./2-5:50 p.m. Section: 21007R/21009R/21011R Location: Online Daniella Segura (Kwong) Office Hours: By appointment Contact Info: [email protected] Course Description Welcome to JOUR 206, Reporting and Writing Practicum (Community Reporting.) This course gives journalism majors hands-on experience in writing digital news for publication on uscannenbergmedia.com. During this weekly lab, students work four consecutive hours for the USC and/or South Los Angeles desks of Annenberg Media, reporting, writing, and distributing stories assigned by student editors with guidance from experienced faculty and coaches. This course runs concurrently with JOUR 207 Reporting and Writing I and JOUR 307 Reporting and Writing II. The practicum is credit/no credit. Student Learning Outcomes ● Identify elements that make a story newsworthy for different audiences ● Identify and use diverse sources in news stories ● Research and verify information for use in news stories on digital platforms and social media ● Write news briefs and stories on deadline and in accordance with professional industry standards under the guidance of student editors and faculty and in collaboration with other student reporters and editors ● Create content for digital and social platforms on deadline and in accordance with professional industry standards and in collaboration with other student reporters and editors ● Apply principles of ethics in real-life news situations Concurrent Enrollment: JOUR 207 Reporting and Writing I or JOUR 307 Reporting and Writing II Description and Assessment of Assignments This class is about hands-on learning. -

Writer's Address Book Volume 1 Newspapers

Gordon Kirkland’s Writer’s Address Book Volume 1 Newspapers 2 The Writer’s Address Book Volume 1 – Newspapers 3 By Gordon Kirkland The Writer’s Address Book Volume 1 - Newspapers By Gordon Kirkland ©2006 4 Also By Gordon Kirkland Books Justice Is Blind – And Her Dog Just Peed In My Cornflakes Never Stand Behind A Loaded Horse When My Mind Wanders It Brings Back Souvenirs The Writer’s Address Book Volume 1 – Newspapers The Writer’s Address Book Volume 2 – Bookstores The Writer’s Address Book Volume 1 – Radio CD’s I’m Big For My Age Never Stand Behind A Loaded Horse… Live! The Writer’s Address Book Volume 1 – Newspapers 5 By Gordon Kirkland Table of Contents Introduction....................................................................................................................... 8 US Dailies ............................................................................................................................ 9 Alabama ........................................................................................................................... 9 Alaska............................................................................................................................. 10 Arkansas......................................................................................................................... 10 Arizona ........................................................................................................................... 11 Colorado ........................................................................................................................ -

Microsoft Outlook

City Council Meeting, March 16, 2021 Public Comments Martha Alvarez From: Brian Bullock <[email protected]> Sent: Monday, March 15, 2021 3:07 PM To: List - City Council Cc: Linda Bullock Subject: [EXTERNAL] Bruce's Beach CAUTION: This Email is from an EXTERNAL source. Ensure you trust this sender before clicking on any links or attachments. MB City Council, Challenging times for sure. I know you feel it. One thing that will help is to not to make it worse by agreeing to do the wrong thing, and that’s to divide our community even more by deviating from the BBTF mission. That would mean going down the path of burdening our fine citizens with a total over-reach. I’ve lived here for 30+ years and I only see citizens that are inclusive and embracing - - 100 years ago is 100 years ago! A lot of incredible, multi-racial progress has been made. If you agree to exceed the mission, some will like it and more won’t. Please reflect, and stay within the boundaries of what the BBTF was set up to do. Staying true to the original goals will hurt some feelings, but is absolutely the most sane option available. Thank you. Brian Bullock 310.488.7784 On Feb 15, 2021, at 12:14 PM, Brian Bullock <[email protected]> wrote: Hello City Council!! As usual, I've been talking with my fellow MB citizens about any number of important political items that can/will impact our wonderful city. Unfortunately, many of them are not positive; only cloaked in what some think is "justice" or "equity". -

Calpers-Entirepublicationlist

Publication Article Count Wall Street Journal 9,011 New York Times 6,878 Los Angeles Times 5,575 Sacramento Bee 3,896 Washington Post 1,975 Bloomberg 1,538 Associated Press 1,368 Reuters 1,029 Pensions & Investments 959 California Healthline 769 San Francisco Chronicle 746 CNN 537 Orange County Register 528 Sacramento Business Journal 516 NASRA 407 Chicago Tribune 395 San Diego Union Tribune 390 Dow Jones 335 Calpensions 320 Barron's 258 San Jose Mercury News 237 Forbes 222 Contra Costa Times 207 USA Today 191 MarketWatch 179 Private Equity International 154 Business Wire 134 Ventura County Star 126 PE Hub 109 San Bernardino County Sun 107 The Bond Buyer 105 AICIO 103 Financial Times 102 Boston Globe 101 Newsweek 91 Fox & Hounds 90 Pittsburgh Post Gazette 89 Riverside Press-Enterprise 88 PR Newswire 87 Capitol Weekly 86 CNBC 85 Public CEO 83 Oakland Tribune 82 Redding Record Seachlight 81 Monterey County Herald 80 Fortune 79 The Street 78 Top 1000 Funds 75 Los Angeles Daily News 73 Marin Independent Journal 72 CBS 72 McClatchy New Service 69 Press Democrat 69 Plan Sponsor 69 Stockton Record 69 CaliforniaHealthline 69 Governing Magazine 68 Inland Valley Daily Bulletin 67 Santa Rosa Press Democrat 64 Modesto Bee 62 St. Louis Post-Dispatch 61 iHealth Beat 60 U-T San Diego 60 San Francisco Business Times 57 Financial News 57 Huffington Post 57 Bond Buyer 57 Desert Sun 57 BenefitsPro 57 Record Searchlight 56 NPR 56 Exchange News Direct 54 Atlanta Journal 52 States News Service 50 BusinessWeek 49 NJ.com 48 Chief Investment Officer 47 Fresno