A Proposed Currency System for Academic Peer Review Payments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOCKETED Before the 12-AAER-2A CALIFORNIA ENERGY COMMISSION Sacramento, CA TN # 70724 MAY 09 2013

California Energy Commssion DOCKETED Before the 12-AAER-2A CALIFORNIA ENERGY COMMISSION Sacramento, CA TN # 70724 MAY 09 2013 In the Matter of ) ) 2013 Appliance Efficiency Pre‐Rulemaking ) ) Docket # 12‐AAER‐2A California Energy Commission ) Appliances & Process Energy Office ) (Game Consoles) Efficiency & Renewable Energy Division ) COMMENTS OF THE ENTERTAINMENT SOFTWARE ASSOCIATION Greggory L. Wheatland Ellison, Schneider & Harris L.L.P. 2600 Capitol Avenue, Suite 400 Sacramento, CA 95816 (916) 447‐2166 ‐ Telephone (916) 447‐3512 – Facsimile [email protected] Attorneys for Entertainment May 9, 2013 Software Association 1 Before the CALIFORNIA ENERGY COMMISSION Sacramento, CA In the Matter of ) ) 2013 Appliance Efficiency Pre-Rulemaking ) ) Docket # 12-AAER-2A California Energy Commission ) Appliances & Process Energy Office ) (Game Consoles) Efficiency & Renewable Energy Division ) COMMENTS OF THE ENTERTAINMENT SOFTWARE ASSOCIATION I. Introduction The Entertainment Software Association (“ESA”) thanks the Commission for this opportunity to provide further information about the video game industry’s products and the strong progress that our industry has made on energy efficiency.1 In the commentary below, we address the specific questions posed by the Commission in the recent webinar. Before turning to those questions, however, we first provide the Commission some context about the game industry’s strong track record on energy efficiency that informs our responses. Game consoles are constantly evolving. Unlike many other consumer electronics, which have a fairly stable feature set or well-understood range of functions, game consoles continue to add new features, functions, and enhanced entertainment experiences. Even its core function, game play, is always evolving in areas such as graphics, network capabilities, multi-player game play, and user interfaces. -

Facultat De Traducció I D'interpretació Grau D

FACULTAT DE TRADUCCIÓ I D’INTERPRETACIÓ GRAU D’ESTUDIS D’ÀSIA ORIENTAL TREBALL DE FI DE GRAU Curs 2015-2016 Situación de la cultura del juego de PC y online en Japón Eva Alabau Gragera 1279352 TUTOR ROBERTO FIGLIULO Barcelona, Juny de 2016 Dades del TFG Títol: Situació de la cultura del joc de PC i online al Japó Situación de la cultura del juego de PC y online en Japón Situation of the PC game and online culture in Japan Autora: Eva Alabau Gragera Tutor: Roberto Figliulo Centre: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Estudis: Grau d’Estudis d’Àsia Oriental Curs acadèmic: 2015 – 2016 Paraules clau Jocs d’ordinador, jocs online, en línia, MMORPG, MMO, videojocs, videoconsola, mòbil, Japó, actualitat. Juegos de ordenador, juegos online, en línea, MMORPG, MMO, videojuegos, videoconsola, móvil, Japón, actualidad. Computer games, online games, online, MMORPG, MMO, videogames, game console, mobile, Japan, now. Resum del TFG Es tracta d’un anàlisi de la desbancada situació actual del sector dels jocs d’ordinador i en línia al Japó, així com la causa per la qual ha acabant sent així. Primer exposo l’estat occidental per a poder comparar-lo després amb les empreses més presents a ambdós bàndols. Comento també els problemes que sorgeixen de la no-localització de videojocs d’ordinador en línia, i els que encapçalen els rànkings d’èxit actualment. La percepció actual i l’estat en que es trova, així com els petits blocs de creixement que pot tenir gràcies a companyies que aposten amb innovació per aquest sector, están també explicats juntament amb el futur que es pot esperar pròximament, sobretot de certes companyies destacables i dels creadors indie. -

Game Developer Power 50 the Binding November 2012 of Isaac

THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE VOL19 NO 11 NOVEMBER 2012 INSIDE: GAME DEVELOPER POWER 50 THE BINDING NOVEMBER 2012 OF ISAAC www.unrealengine.com real Matinee extensively for Lost Planet 3. many inspirations from visionary directors Spark Unlimited Explores Sophos said these tools empower level de- such as Ridley Scott and John Carpenter. Lost Planet 3 with signers, artist, animators and sound design- Using UE3’s volumetric lighting capabilities ers to quickly prototype, iterate and polish of the engine, Spark was able to more effec- Unreal Engine 3 gameplay scenarios and cinematics. With tively create the moody atmosphere and light- multiple departments being comfortable with ing schemes to help create a sci-fi world that Capcom has enlisted Los Angeles developer Kismet and Matinee, engineers and design- shows as nicely as the reference it draws upon. Spark Unlimited to continue the adventures ers are no longer the bottleneck when it “Even though it takes place in the future, in the world of E.D.N. III. Lost Planet 3 is a comes to implementing assets, which fa- we defi nitely took a lot of inspiration from the prequel to the original game, offering fans of cilitates rapid development and leads to a Old West frontier,” said Sophos. “We also the franchise a very different experience in higher level of polish across the entire game. wanted a lived-in, retro-vibe, so high-tech the harsh, icy conditions of the unforgiving Sophos said the communication between hardware took a backseat to improvised planet. The game combines on-foot third-per- Spark and Epic has been great in its ongoing weapons and real-world fi rearms. -

Faculdade De Filosofia Letras E Ciências Humanas Departamento De Letras Modernas Projeto De Pesquisa Para O Mestrado: Estudos Da Tradução

Faculdade de Filosofia Letras e Ciências Humanas Departamento de Letras Modernas Projeto de Pesquisa para o Mestrado: Estudos da Tradução Candidato: Ricardo Vinicius Ferraz de Souza Orientador: Professor John Milton São Paulo, 15 de maio de 2012. 1 SUMÁRIO 1. OBJETIVOS ....................................................................................................................... 03 2. JUSTIFICATIVA ............................................................................................................... 03 3. DESCRIÇÃO ...................................................................................................................... 04 3.1. PERSPECTIVA HISTÓRICA .............................................................................. 04 3.2. A LOCALIZAÇÃO DE JOGOS NO BRASIL .................................................... 07 3.3. ASPECTOS TEÓRICOS ....................................................................................... 08 4. METODOLOGIA ............................................................................................................... 10 5. CRONOGRAMA ................................................................................................................ 11 6. BIBLIOGRAFIA ................................................................................................................ 11 7. REFERÊNCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS ............................................................................. 15 2 1. OBJETIVO Este projeto de pesquisa tem por objetivo analisar a tradução e localização -

2010 Resource Directory & Editorial Index 2009

Language | Technology | Business RESOURCE ANNUAL DIRECTORY EDITORIAL ANNUAL INDEX 2009 Real costs of quality software translations People-centric company management 001CoverResourceDirectoryRD10.ind11CoverResourceDirectoryRD10.ind1 1 11/14/10/14/10 99:23:22:23:22 AMAM 002-032-03 AAd-Aboutd-About RD10.inddRD10.indd 2 11/14/10/14/10 99:27:04:27:04 AMAM About the MultiLingual 2010 Resource Directory and Editorial Index 2009 Up Front new year, and new decade, offers an optimistically blank slate, particularly in the times of tightened belts and tightened budgets. The localization industry has never been affected quite the same way as many other sectors, but now that A other sectors begin to tentatively look up the economic curve towards prosperity, we may relax just a bit more also. This eighth annual resource directory and index allows industry professionals and those wanting to expand business access to language-industry companies around the globe. Following tradition, the 2010 Resource Directory (blue tabs) begins this issue, listing compa- nies providing services in a variety of specialties and formats: from language-related technol- ogy to recruitment; from locale-specifi c localization to educational resources; from interpreting to marketing. Next come the editorial pages (red tabs) on timeless localization practice. Henk Boxma enumerates the real costs of quality software translations, and Kevin Fountoukidis offers tips on people-centric company management. The Editorial Index 2009 (gold tabs) provides a helpful reference for MultiLingual issues 101- 108, by author, title, topic and so on, all arranged alphabetically. Then there’s a list of acronyms and abbreviations used throughout the magazine, a glossary of terms, and our list of advertisers for this issue. -

Business Results for the Fiscal Year Ended March 31, 2011

From “Made in Japan” to “Checked by Japan” Business Results for the Fiscal Year Ended March 31, 2011 DIGITAL Hearts Co., Ltd. Eiichi Miyazawa, President & CEO From “Made in Japan” to “Checked by Japan” Contents 1. Business Results for FY03/11 P 3 2. Earnings Forecast for FY03/12 P14 3. FY03/12: Future Initiatives P17 Major Moves in FY03/11 (Publicly Disclosed Information) 4/13/10 Mobile content services for Android phones launched 5/7/10 Glitch cases registered on fuguai.com surpass 10,000-mark 8/26/10 Exclusive test booth set up for Xbox 360 Kinect 9/17/10 Localized support services for Yahoo! Mobage and Mobage town launched 11/12/10 Entered into business alliance with Active Gaming Media Co., Ltd. 1/14/11 Entered into business alliance with E-Guardian Co., Ltd. 1/28/11 3D content production started 2/22/11 Selected as alliance service vendor for GREE games 3 Business Results Summary FY03/10 FY03/11 FY03/11 Year-on-Year (\ Million) Actual Results Initial Forecast Actual Results Change Net Sales 3,416 4,068 3,957 115.8% Operating Income 521 620 528 101.3% Ordinary Income 526 618 495 94.1% Net Income 306 330 278 91.0% Ordinary Income Margin 15.4% 15.2% 12.5% △2.9 points Net Sales: Reached 115.8% yoy growth Operating Income: Due to higher labor and new business preparation costs, only generated 101.3% yoy growth Ordinary Income: Market fluctuations led to 94.1% yoy decline 4 Ratio of Net Sales by Business Unit FY03/10 FY03/11 Year-on-Year (\ Million) Actual Results Actual Results Change Consumer Games Unit 1,964 1,896 96.5% Mobile -

Gaming PC WORLD 1

GAME-Dancing Your Heart OFFIClAL REPORT Organizer: Computer Entertainment Supplier's Association(CESA) Co-Organizer: Nikkei Business Publications, Inc(. Nikkei BP) Supporter: Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry(METI) Period: Sep.15(Thursday)-18(Sunday), 2011 Venue: Makuhari Messe 1 Outline of the Show Name : TOKYO GAME SHOW 2011 Theme : GAME-Dancing Your Heart Organizer : Computer Entertainment Supplier's Association(CESA) Co-Organizer : Nikkei Business Publications, Inc(. Nikkei BP) Supporter : Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry(METI) Period : Business Days Sep. 15(Thursday) - Sep. 16(Friday) From 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Public Days Sep. 17(Saturday) - Sep. 18(Sunday) From 9:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Venue: Makuhari Messe(Mihama-ku, Chiba-shi, Chiba) Exhibition Halls 1-8(exhibition area : about 54,000 square meters) International Conference Hall Number of exhibitors : 193 Number of booths : 1,250 booths Displayed titles : 736 titles(number of advance registrations) By platform(%) By genre(%) PC 18.1 PlayStation 3 5.3 Action 12.5 Smartphone 13.5 PlayStation Portable 5.3 Role Playing 8.2 iPhone (6.5)Nintendo DS 5.2 Shooting 4.8 Android (6.4)Xbox 360 5.2 Puzzle 4.6 Smartphone(other) (0.6)Table(t iPad/ Android /Windows7,etc) 4.6 Simulation 4.5 Nintendo 3DS 8.8 PlayStation Vita 1.5 Adventure 4.2 Mobile phone 7.2 Wii 1.5 Sports 2.3 NTT docomo (2.5)PlayStation 2 0.1 Racing 2.0 Softbank (2.2)Wii U 0.1 Othe(r genre) 21.1 ※1 au (2.0)New-generation console 0 Development tools 3.1 ※2 WILLCOM (0.1)Other 23.6 Peripherals 9.9 em (0.1) Othe(r good,etc) 22.8 Mobile phones TBD (0.3) ※1 Next generation platform :platform which will be sold in aftertime. -

Video Game Localization: the Case of Brazil

Video game localization: the case of Brazil Ricardo Vinicius Ferraz de Souza* Abstract: When the first video games appeared back in the 1950's, they presented themselves as a technology with great potential and a bright future. What not many people expected is that, nearly half a century later, video games would become a multibillion dollar industry, rivaling other important industries of the entertainment world such as the film and the music industries in terms of revenue and popularity. With the growing expansion of the sector, combined with the necessity of making their games global, many developers and publishers are increasingly investing in translation and localization. This paper gives an overview on the relation between video games and translation at different stages of the development and evolution of the industry. It also addresses, through the analyses of a number of games, the different stages of video game localization in Brazil, with its particularities and idiosyncrasies. The analysis is based on the concept of “gameplay experience” by Mangiron and O’Hagan, in addition to making use of other principles presented by Bernal Merino, Scholand and Dietz. It also focuses on the historical development of video games in Brazil and the way translation is utilized and displayed on the screen from the perspective of a video game player. Keywords: Video Games; translation; localization; video game localization in Brazil. Resumo: Quando os primeiros videogames apareceram na década de 1950, eles se apresentaram como uma tecnologia de grande potencial e com um futuro promissor. O que muitos não esperavam é que, cerca de meio século depois, o videogame se tornaria uma indústria multibilionária, rivalizando com outras indústrias importantes do mundo do entretenimento em termos de faturamento e popularidade, tais como as indústrias do cinema e da música. -

Master Reference

Master Les effets des erreurs de traduction dans la localisation des jeux vidéo (L'exemple de The Elder Scrolls : IV Oblivion) ROH, Florence Abstract Ce mémoire traite de la localisation des jeux vidéo et de l'impact des erreurs de traduction sur l'expérience de jeu. Reference ROH, Florence. Les effets des erreurs de traduction dans la localisation des jeux vidéo (L'exemple de The Elder Scrolls : IV Oblivion). Master : Univ. Genève, 2011 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:17295 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 FLORENCE ROH LES EFFETS DES ERREURS DE TRADUCTION DANS LA LOCALISATION DES JEUX VIDÉO (L’exemple de THE ELDER SCROLLS IV : OBLIVION ) Mémoire présenté à l'Ecole de traduction et d'interprétation pour l'obtention du Master en traduction, mention traduction spécialisée Directeur de mémoire : Mme Mathilde Fontanet Juré : Prof. Susan Armstrong Université de Genève Septembre 2011 Florence Roh Septembre 2011 SOMMAIRE INTRODUCTION CHAPITRE I – DÉFINITIONS • Quelques définitions o La localisation ° Qu’est-ce que la localisation ? ° Les différents aspects du processus de localisation ° Bref historique de la localisation o Le jeu vidéo • Les différents types de jeux vidéo o Les genres o Les supports o Le niveau de réalisme CHAPITRE II – LA LOCALISATION DES JEUX VIDÉO • Pourquoi localiser un jeu vidéo ? • Les niveaux de localisation • La localisation des jeux vidéo et des autres multimédias • Les différents types d’erreurs courantes dans les jeux vidéo CHAPITRE III – ETUDE DE CAS SUR THE ELDER SCROLLS IV – OBLIVION • Présentation du jeu The Elder Scrolls IV : Oblivion • Présentation du studio de développement Bethesda Softworks • La problématique, la méthode et les parties analysées • Relevé des erreurs et analyse • Bilan de la partie analytique CONCLUSION LEXIQUE DES TERMES RELATIFS AUX JEUX VIDÉO BIBLIOGRAPHIE TABLE DES MATIÈRES ANNEXES - 3/187- Florence Roh Septembre 2011 INTRODUCTION Ce mémoire a pour thème la localisation des jeux vidéo. -

This Checklist Is Generated Using RF Generation's Database This Checklist Is Updated Daily, and It's Completeness Is Dependent on the Completeness of the Database

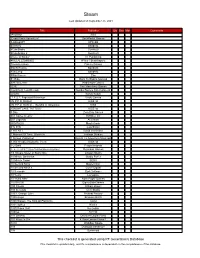

Steam Last Updated on September 25, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments !AnyWay! SGS !Dead Pixels Adventure! DackPostal Games !LABrpgUP! UPandQ #Archery Bandello #CuteSnake Sunrise9 #CuteSnake 2 Sunrise9 #Have A Sticker VT Publishing #KILLALLZOMBIES 8Floor / Beatshapers #monstercakes Paleno Games #SelfieTennis Bandello #SkiJump Bandello #WarGames Eko $1 Ride Back To Basics Gaming √Letter Kadokawa Games .EXE Two Man Army Games .hack//G.U. Last Recode Bandai Namco Entertainment .projekt Kyrylo Kuzyk .T.E.S.T: Expected Behaviour Veslo Games //N.P.P.D. RUSH// KISS ltd //N.P.P.D. RUSH// - The Milk of Ultraviolet KISS //SNOWFLAKE TATTOO// KISS ltd 0 Day Zero Day Games 001 Game Creator SoftWeir Inc 007 Legends Activision 0RBITALIS Mastertronic 0°N 0°W Colorfiction 1 HIT KILL David Vecchione 1 Moment Of Time: Silentville Jetdogs Studios 1 Screen Platformer Return To Adventure Mountain 1,000 Heads Among the Trees KISS ltd 1-2-Swift Pitaya Network 1... 2... 3... KICK IT! (Drop That Beat Like an Ugly Baby) Dejobaan Games 1/4 Square Meter of Starry Sky Lingtan Studio 10 Minute Barbarian Studio Puffer 10 Minute Tower SEGA 10 Second Ninja Mastertronic 10 Second Ninja X Curve Digital 10 Seconds Zynk Software 10 Years Lionsgate 10 Years After Rock Paper Games 10,000,000 EightyEightGames 100 Chests William Brown 100 Seconds Cien Studio 100% Orange Juice Fruitbat Factory 1000 Amps Brandon Brizzi 1000 Stages: The King Of Platforms ltaoist 1001 Spikes Nicalis 100ft Robot Golf No Goblin 100nya .M.Y.W. 101 Secrets Devolver Digital Films 101 Ways to Die 4 Door Lemon Vision 1 1010 WalkBoy Studio 103 Dystopia Interactive 10k Dynamoid This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Videojuegos Y Localización: Análisis De La Industria En Japón Y En España

MÁSTER EN ASIA ORIENTAL – ESTUDIOS JAPONESES CURSO 2012-2014 TRABAJO FIN DE MÁSTER Videojuegos y localización: análisis de la industria en Japón y en España Autora: Sara Capilla Torres [[email protected]] Tutora: Masako Kubo Salamanca, 14 de julio de 2014 ÍNDICE Introducción ........................................................................................................... 1 1 El mercado japonés de los videojuegos................................................................ 2 1.1 Evolución histórica ................................................................................. 2 1.2 Características específicas ....................................................................... 8 2 El mercado español de los videojuegos................................................................ 11 2.1 Evolución histórica ................................................................................. 11 2.2 Características específicas ....................................................................... 14 3 En una sigla: GILT (Globalization, Internationalization, Localization, Translation)............................................................................................................ 16 4 Los videojuegos y la narrativa transmediática ..................................................... 19 5 Localización cultural, censura, transcreación y estrategias de localización........... 21 Conclusiones .......................................................................................................... 29 Referencia bibliográfica -

Slator 2018 Gaming Localization Report

Slator 2019 Game Localization Report with compliments [email protected] Gaming Localization Report | Slator.com How To Use This Report Slator's easy-to-digest research offers the very latest industry and data analysis, providing language service providers and end-clients the confidence to make informed and time critical decisions. It is a cost-effective, credible resource for busy professionals. Disclaimer The mention of any public or private entity in this report does not constitute an official endorsement by Slator. The information used in this report is either compiled from publicly accessible resources (e.g. pricing web pages for technology providers), acquired directly from company representatives, or both. The insights and opinions from Slator’s expert contributors are theirs alone, and Slator does not necessarily share the same position where opinions are attributed to respondents. Acknowledgements Slator would like to thank the following for their time, guidance, and insight, without which this report could not have come into fruition: Michaela Bartelt-Krantz, Senior Localization Director, Electronic Arts Andrew Day, CEO, Keywords Studios Jasmin Jelača, Localization Lead, Nordeus Dominick Kelley, Client Solutions Manager, XTM International Mike Kim, Localization Director, Tencent America David Lakritz, CEO, LAI Global Game Services Slator Reports Slator Tyler Long, CEO, TriggerCore Lucas Mendes, Creative Lead and Localization Head, Level Up Brazil Karin Skoog, Consultant, LAI Global Game Services Artjom Vitsjuk, Localization Project