Mother to Mother Study Guide V2 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Leaders in Grassroots Organizations

Crossing Boundaries: Bridging the Racial Divide – South Africa Taught by Rev. Edwin and Organized by Melikaya Ntshingwa COURSE DESCRIPTION This is a contextual theology course based on the South African experience of apartheid, liberation and transformation, or in the terms of our course: theological discourses from South Africa on “bridging the racial divide”. The course has developed over years – its origins go back to the Desmond Tutu Peace Centre of which the course founder, Dr Judy Mayotte was a Board member. We will look first at the South African experience of Apartheid and try to understand how it was that Christians came to develop such a patently evil form of governance as was Apartheid. We will explore several themes that relate to Apartheid, such as origins, identity, experience, struggle and separation. Then you will have a chance to examine your own theology, where it comes from and how you arrived at your current theological position. In this regard the course also contains sources that deal with Catholic approaches to identity and race. Together we shall then explore issues relating to your own genesis, identity, experience, struggle and separation – all issues common to humankind! All of this we will do by seeking to answer various questions. Each question leads to discussion in class and provides the basis for the work you will be required to do. In the course we examine the nature of separateness (apartheid being an ideology based on a theology of separateness). We will explore the origins of separateness and see how it effects even ourselves at a most basic and elementary level. -

Plant a Tree

ADDRESS BY THE MINISTER OF WATER AFFAIRS & FORESTRY, RONNIE KASRILS, AT A TREE PLANTING IN MEMORY OF THE MURDER OF THE GUGULETHU SEVEN & AMY BIEHL Arbor Day, Gugulethu, 31st August 1999 I am very honoured to have this opportunity to greet you all. And today I want to extend a special message to all of you who experienced the terrible events that happened here in Gugulethu in the apartheid years. And also, after the disaster that struck early on Sunday morning, the great losses you are suffering now. I am here today in memory and in tribute of all the people of Gugulethu. I salute the courage you have shown over the years. And I want to express my deep sympathy and concern for the plight of those who have lost their family and friends, their homes and their property in the last few days. This commemoration has been dedicated to eight people. Eight people who were senselessly slaughtered right here in this historical community. The first event took place at about 7.30 in the morning on 3 March 1986 when seven young men were shot dead at the corner of NY1 and NY111 and in a field nearby. There names were Mandla Simon Mxinwa, Zanisile Zenith Mjobo, Zola Alfred Swelani, Godfrey Miya, Christopher Piet, Themba Mlifi and Zabonke John Konile. All seven were shot in the head and suffered numerous other gunshot wounds. Every one here knows the story of how they were set up by askaris and drove into a police trap. Just seven and a half years later, on 25 August 1993, Amy Elizabeth Biehl drove into Gugulethu to drop off some friends. -

Annual Award Expanding to Students, Faculty

IN SIDE Winter break is just a month away. Check out our & list of films to i'o watch. •news press Volume 49 ·Issue 1 1 www.kapionewspress.com 11.15.10 Annual award Clubs gather in friendly competition expanding to students, faculty For the first time, YELTs will know that, but they're not the only ones excellent on campus;' he said. honor students and faculty "We want to recognize staff (like) in addition to instructors. janitors, maintenance workers (and) clerical workers. All those people are By Joie Nishimoto . a part of the campus, and we don't ED ITOR -IN-CH IEF get to see them. For the first time, Kapi'olani Com We only recog munity College's Excellence in Teach nize them when ing Awards (ETA) will be extending things don't get its recognition and appreciation to done, but these not just professors, but to students people actually and faculty as well. work hard:' Now called the Year of Excel- In addition lence in Learning, Teaching and Sup- Ford to faculty, the port (YELTS), this award identifies YELTS will begin accomplished individuals who were to recognize students. nominated by their peers. "That's most important;' Ford said. Staff members will have the chance "We're here for the students to learn. to be awarded beginning this year. Why is our faculty excellent? Because According to Shawn Ford, Faculty they have excellent students:' Student Relations Committee chair According to Ford, he wants to man, KCC does not have an award have awards for Chartered Student SEAN NAKAMURA/KAPI'O for excellent staff members, but said Organizations (CSO), such as for Students from the Radiology Technology team trek across the pavement in front of the 'Ohi'a cafeteria using that other campuses like UH-Manoa Board of Student Activities, Board paper plates as a "lily" to venture on top "lava," one of the few games that was played on Field Day. -

The Promise of Forgiveness Inner Healing Is a Path to Social Revolution

RESTORATIVE JUSTICE The Promise of Forgiveness Inner Healing is a Path to Social Revolution Sarah Elizabeth Clark would she ever want to? Why does this move and inspire us? What can we learn from this amazing story and from welve years ago, near Cape Town, South Africa, four others like it? T South African men, Easy Nofemela, Ntobeko Peni, The process of forgiveness is not merely sentimental, it and two others, murdered Amy Biehl, a white American is extremely transformative. It is transformative because it Fulbright scholar. When South Africa’s Truth and creates a new relationship between the perpetrator and Reconciliation Commission granted the men amnesty for the victim. Through the act of forgiveness, an individual is their crime in 1998, Amy Biehl’s parents supported the able to overcome his or her victimhood, feel empathy for decision. their ‘enemy,’ and ultimately re- Linda Biehl, Amy’s mother, humanize the person who did wrote in an article called “Forgiveness is not just an occasional them wrong. As we will also “Making Change” in the Fall act; it is a permanent attitude.” see, the act of forgiveness on 2004 issue of Greater Good -Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. community, national and inter- magazine, “Easy and Ntobeko national levels can even pro- needed to confess and tell the mote a new political world truth in order to receive amnesty, and there was a genuine order based on cooperation and dialogue, rather than quality to their testimony. I had to get outside of myself threat and violence. and realize that these people lived in an environment that I’m not sure I could have survived in. -

Die Flexible Welt Der Simpsons

BACHELORARBEIT Herr Benjamin Lehmann Die flexible Welt der Simpsons 2012 Fakultät: Medien BACHELORARBEIT Die flexible Welt der Simpsons Autor: Herr Benjamin Lehmann Studiengang: Film und Fernsehen Seminargruppe: FF08w2-B Erstprüfer: Professor Peter Gottschalk Zweitprüfer: Christian Maintz (M.A.) Einreichung: Mittweida, 06.01.2012 Faculty of Media BACHELOR THESIS The flexible world of the Simpsons author: Mr. Benjamin Lehmann course of studies: Film und Fernsehen seminar group: FF08w2-B first examiner: Professor Peter Gottschalk second examiner: Christian Maintz (M.A.) submission: Mittweida, 6th January 2012 Bibliografische Angaben Lehmann, Benjamin: Die flexible Welt der Simpsons The flexible world of the Simpsons 103 Seiten, Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Bachelorarbeit, 2012 Abstract Die Simpsons sorgen seit mehr als 20 Jahren für subversive Unterhaltung im Zeichentrickformat. Die Serie verbindet realistische Themen mit dem abnormen Witz von Cartoons. Diese Flexibilität ist ein bestimmendes Element in Springfield und erstreckt sich über verschiedene Bereiche der Serie. Die flexible Welt der Simpsons wird in dieser Arbeit unter Berücksichtigung der Auswirkungen auf den Wiedersehenswert der Serie untersucht. 5 Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis ............................................................................................. 5 Abkürzungsverzeichnis .................................................................................... 7 1 Einleitung ................................................................................................... -

Concert History of the Allen County War Memorial Coliseum

Historical Concert List updated December 9, 2020 Sorted by Artist Sorted by Chronological Order .38 Special 3/27/1981 Casting Crowns 9/29/2020 .38 Special 10/5/1986 Mitchell Tenpenny 9/25/2020 .38 Special 5/17/1984 Jordan Davis 9/25/2020 .38 Special 5/16/1982 Chris Janson 9/25/2020 3 Doors Down 7/9/2003 Newsboys United 3/8/2020 4 Him 10/6/2000 Mandisa 3/8/2020 4 Him 10/26/1999 Adam Agee 3/8/2020 4 Him 12/6/1996 Crowder 2/20/2020 5th Dimension 3/10/1972 Hillsong Young & Free 2/20/2020 98 Degrees 4/4/2001 Andy Mineo 2/20/2020 98 Degrees 10/24/1999 Building 429 2/20/2020 A Day To Remember 11/14/2019 RED 2/20/2020 Aaron Carter 3/7/2002 Austin French 2/20/2020 Aaron Jeoffrey 8/13/1999 Newsong 2/20/2020 Aaron Tippin 5/5/1991 Riley Clemmons 2/20/2020 AC/DC 11/21/1990 Ballenger 2/20/2020 AC/DC 5/13/1988 Zauntee 2/20/2020 AC/DC 9/7/1986 KISS 2/16/2020 AC/DC 9/21/1980 David Lee Roth 2/16/2020 AC/DC 7/31/1979 Korn 2/4/2020 AC/DC 10/3/1978 Breaking Benjamin 2/4/2020 AC/DC 12/15/1977 Bones UK 2/4/2020 Adam Agee 3/8/2020 Five Finger Death Punch 12/9/2019 Addison Agen 2/8/2018 Three Days Grace 12/9/2019 Aerosmith 12/2/2002 Bad Wolves 12/9/2019 Aerosmith 11/23/1998 Fire From The Gods 12/9/2019 Aerosmith 5/17/1998 Chris Young 11/21/2019 Aerosmith 6/22/1993 Eli Young Band 11/21/2019 Aerosmith 5/29/1986 Matt Stell 11/21/2019 Aerosmith 10/3/1978 A Day To Remember 11/14/2019 Aerosmith 10/7/1977 I Prevail 11/14/2019 Aerosmith 5/25/1976 Beartooth 11/14/2019 Aerosmith 3/26/1975 Can't Swim 11/14/2019 After Seven 5/19/1991 Luke Bryan 10/23/2019 After The Fire -

Time Within Sindiwe Magona's Mother to Mother and Zakes Mda's

―THE RISING OF THE NEW SUN‖: TIME WITHIN SINDIWE MAGONA‘S MOTHER TO MOTHER AND ZAKES MDA‘S HEART OF REDNESS A thesis presented to the faculty of the Graduate School of Western Carolina University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English. By Heather P. Williams Director: Dr. Laura Wright Associate Professor of English English Department Committee Members: Dr. Elizabeth Heffelfinger, English Dr. Nyaga Mwaniki, Anthropology April 2011 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like thank my committee Dr. Laura Wright, Dr. Elizabeth Heffelfinger, and Dr. Nyaga Mwaniki for their assistance and support while writing my thesis. In particular, I would like to thank Dr. Wright for her direction, motivation, and encouragement throughout the research, writing, and editing process. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................ii Table of Contents .......................................................................................................iii Abstract ......................................................................................................................iv Chapter 1: ―The Sun will Rise‖ – Time in the Xhosa Cattle Killing and the South African Nation ...............................5 Chapter 2: ―The Difference of One Sun‘s Rise‖ – Conflicting Time in Sindiwe Magona‘s Mother to Mother ......................................22 Chapter 3: ―The Past. It Did Not Happen‖ – Ritual Memory Time in Zakes Mda‘s Heart -

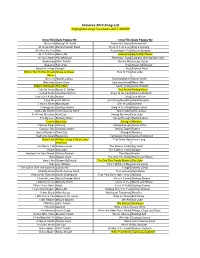

Immerse Song List.Xlsx

Immerse 2014 Song List *Highlighted songs have been JUST ADDED* Song Title Made Popular By Song Title Made Popular By Above All Michael W. Smith Praise His Name Ashmont Hill All Around Me David Crowder Band Proof of Your Love King & Country All I Need is You Adie Reaching for You Lincoln Brewster All of Creation Mercy Me Redeemed Big Daddy Weave At Your Name Phil Wickham Revelation Song Gateway Worship/Kari Jobe Awakening Chris Tomlin Revive Me Jeremy Camp Beautiful Kari Jobe Rise Shawn McDonald Beautiful Things Gungor Run Addison Road Before The Throne of God Shane & Shane Run to You Kari Jobe Above Blessed Rachel Lampa Rushing Waters Dustin Smith Blessings Laura Story Safe and Sound Mercy Me Broken Hallelujah The Afters Savior to Me Kerrie Roberts Call On Jesus Nicole C. Mullen Say Amen Finding Favor Called To Be Jonathan Nelson Shout to the Lord Darlene Zschech Can't Live A Day Avalon Sing Josh Wilson Carry Me Josh Wilson Something Beautiful Needtobreathe Christ is Risen Matt Maher Son of God Starfield Courageous Casting Crowns Song to the King Natalie Grant Empty My Hands Tenth Avenue North Starry Night Chris August For Every Mountain Kurt Carr Steady My Heart Kari Jobe For My Love Bethany Dillon Strong Enough Matthew West Forever Kari Jobe Stronger Mandisa Forever Reign Hillsong Strong Enough Stacie Orrico Glorious Day Casting Crowns Strong Tower Kutless God of Wonders Third Day Stronger Mandisa God's Not Dead Newsboys Temporary Home Carrie Underwood Great I Am Phillips, Craig & Dean/Jared That Great Day Jonny Lang Anderson He Wants -

Kappale Artisti

14.7.2020 Suomen suosituin karaokepalvelu ammattikäyttöön Kappale Artisti #1 Nelly #1 Crush Garbage #NAME Ednita Nazario #Selˆe The Chainsmokers #thatPOWER Will.i.am Feat Justin Bieber #thatPOWER Will.i.am Feat. Justin Bieber (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderˆnger (Barry) Islands In The Stream Comic Relief (Call Me) Number One The Tremeloes (Can't Start) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue (Doo Wop) That Thing Lauren Hill (Every Time I Turn Around) Back In Love Again LTD (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Brandy (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Bryan Adams (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody Wrong Song B. J. Thomas (How Does It Feel To Be) On Top Of The W England United (I Am Not A) Robot Marina & The Diamonds (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction The Rolling Stones (I Could Only) Whisper Your Name Harry Connick, Jr (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (If Paradise Is) Half As Nice Amen Corner (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Shania Twain (I'll Never Be) Maria Magdalena Sandra (It Looks Like) I'll Never Fall In Love Again Tom Jones (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley-Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life (Duet) Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (Just Like) Romeo And Juliet The Re˜ections (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon (Marie's The Name) Of His Latest Flame Elvis Presley (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley (Reach Up For The) Sunrise Duran Duran (Shake, Shake, Shake) Shake Your Booty KC And The Sunshine Band (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding (Theme From) New York, New York Frank Sinatra (They Long To Be) Close To You Carpenters (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets (Where Do I Begin) Love Story Andy Williams (You Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears (You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party!) The Beastie Boys 1+1 (One Plus One) Beyonce 1000 Coeurs Debout Star Academie 2009 1000 Miles H.E.A.T. -

Interview with Sindiwe Magona

Il Tolomeo [online] ISSN 2499-5975 Vol. 17 – Dicembre | December | Décembre 2015 [print] ISSN 1594-1930 Interview with Sindiwe Magona Maria Paola Guarducci (Università degli Studi Roma Tre, Italia) Sindiwe Magona (1943) was born in the Transkei and grew up in the Cape Flats (Cape Town). She holds degrees from the University of London, the University of South Africa and Columbia University. She lived for a long time in New York where she worked for the United Nations and returned permanently to South Africa in 2003. She is involved in creative writing projects mainly addressed to women living in the townships of Cape Town. Magona has received many prizes for her literary works and is among the most prestigious writers of her country. She is the author of two autobi- ographies (To My Children’s Children, 1990 and Forced to Grow, 1998), two novels (Mother to Mother, 1998 and Beauty’s Gift, 2008), one col- lection of poems (Please, Take Photographs, 2009), various collections of short stories and many books for children and adolescents (among which the novel Life is Hard but a Beautiful Thing, 1998). Just as Bessie Head, Miriam Tlali, Ellen Kuzwayo, and Agnes Sam have, so Magona has used writing not only like a weapon against apartheid but also, sharply and up to date, against the patriarchal structure of South African autochthonous culture which oppressed black women almost as much and as viciously as racism did. Her acclaimed novel, Mother to Mother, which has been recently re-published in Italian (Da madre a madre, Italian translation by Rosaria Contestabile, Baldini & Castoldi, 2015, pp. -

'Long Night's Journey Into Day: South Africa's Search for Truth and Reconciliation'

H-SAfrica Klausen on , 'Long Night's Journey Into Day: South Africa's Search for Truth and Reconciliation' Review published on Tuesday, January 1, 2002 Long Night's Journey Into Day: South Africa's Search for Truth and Reconciliation. Iris Films. Reviewed by Susanne Klausen Published on H-SAfrica (January, 2002) [editor's note: H-SAfrica is pleased to present this review essay from Susanne Klausen, whose critique comes from the perspectives both of a historian of South Africa and a documentary film producer (she is co-producer, with Don Gill, of the documentary 'The Plywood Girls,' (1999).--P.L.] <p> <cite>Long Night's Journey Into Day</cite> is a film documentary about the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC or Commission). The TRC was established in 1995 by the country's first democratically elected Parliament. According to former Justice Minister Dullah Omar, who introduced the Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act (1995) that created the Commission, the TRC was envisaged as part of the bridge-building process designed to help lead the nation away from a deeply divided past to "a future founded on the recognition of human rights, democracy and peaceful co-existence."[1] Its overarching mandate was to promote national unity and reconciliation. In order to fulfill it, the TRC set out to uncover "as complete a picture as possible" of the gross human rights violations committed between 1960 and 1994 (from the Sharpeville Massacre to the election of the first democratic government), in the belief that telling the truth about the violations from the various perspectives of those involved would lead to greater understanding and reconciliation between South Africans.