The Future of the National Flood Insurance Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Steps Forward, Two Steps Back: Tobacco Policy Making in Nebraska

UCSF Tobacco Control Policy Making: United States Title Three Steps Forward, Two Steps Back: Tobacco Policy Making in Nebraska Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/70r843c4 Authors Wessel, Andrew Ibrahim, Jennifer K., Ph.D. Glantz, Stanton A., Ph.D. Publication Date 2004-04-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Three Steps Forward, Two Steps Back: Tobacco Policy Making in Nebraska Andrew Wessel Jennifer Ibrahim, Ph.D. Stanton A. Glantz, Ph.D. Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education School of Medicine University of California, San Francisco San Francisco, CA 94143-1390 April 2004 Three Steps Forward, Two Steps Back: Tobacco Policy Making in Nebraska Andrew J. Wessel Jennifer K. Ibrahim, Ph.D. Stanton A. Glantz, Ph.D. Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education School of Medicine University of California, San Francisco San Francisco, CA 94143-1390 April 2004 Supported in part by CA-61021. Copyright 2004 by A. J. Wessel, J. K. Ibrahim and S. A. Glantz. Permission is granted to reproduce this report for nonprofit purposes designed to promote the public health, so long as this report is credited. This report is available on the World Wide Web at http://repositories.cdlib.org/ctcre/tcpmus/NE2004. This report is one of a series of reports that analyze tobacco industry campaign contributions, lobbying, and other political activity in Nebraska and other states. The other reports are available on the World Wide Web at http://repositories.cdlib.org/ctcre/. 1 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • In 2002, 22.7% of Nebraskans over the age of 18 were current smokers, accounting for approximately 389,000 smokers. -

ASDSO Membership

Association of State Dam Safety Officials Annual Report July 2006 - June 2007 Association of State Dam Safety Officials 450 Old Vine St. Lexington, KY 40507 The Association of State Dam Safety Officials 2007 Annual Report documents progress toward the financial and strategic planning goals set for this fiscal year. The fiscal year cycle takes into account activities from July 1, 2006 to June 30, 2007. The report follows the format of ASDSO’s Strategic Plan. Respectfully submitted, 2006-07 ASDSO Board of Directors James W. Gallagher, P.E. (President), New Hampshire Robert B. Finucane, P.E., Vermont Kenneth E. Smith, P.E. (Past President), Indiana David A. Gutierrez, P.E., California Mark B. Ogden, P.E. (President-Elect), Ohio John H. Moyle, P.E., New Jersey Steven M. Bradley, P.E.(Treasurer), South Carolina Stephen Partney, P.E., Florida; replaced in mid-term by James MacLellan, Mississippi Robert K. Martinez, P.E. (Secretary), Nevada Randy Bass., P.E., Affiliate Member Advisory Committee Chair James L. Alexander, P.E., Missouri Staff Jason Boyle, P.E., North Dakota; replaced in mid-term by Doug Johnson, Washington Lori C. Spragens, Executive Director Jack Byers, P.E., Colorado Susan A. Sorrell, Membership & Meetings Director Max Fowler, P.E., North Carolina Sarah M. Mayfield, Information Specialist Maureen C. Hogle, Promotions and Marketing Members of the 2006-07 Board (L to R) Randy Bass (Affiliate Member Advisory Committee Chair), Jim Alexander (MO), Max Fowler (NC), David Gutierrez (CA), Mark Ogden (OH)(President-Elect), Steve Partney (FL)(replaced in mid-term by James MacLellan [MS]), Bob Finucane (VT), Ken Smith (IN)(Past President), John Moyle (NJ), Jim Gallagher (NH)(President), Jason Boyle (ND)(replaced in mid-term by Doug Johnson [WA]), Steve Bradley (SC)(Treasurer), Jack Byers (CO), and Rob Martinez (NV)(Secretary). -

HAZUS Conference Program

CONNECTING THE PIECES FOR MITIGATION AUGUST 10-12, 2009 Jane S. McKimmon Center NC State’s Extension and Continued Education Conference Center Raleigh, North Carolina 3rd ANNUAL HAZUS CONFERENCE 3rd ANNUAL HAZUS CONFERENCE Raleigh, North Carolina Raleigh, North Carolina WELCOME TO THE 3RD ANNUAL HAZUS-MH CONFERENCE On behalf of the Federal Emergency Management Agency and its partners, I welcome you to the 2009 Annual HAZUS-MH Conference. July 30, 2009 This year’s conference brings together a unique group of almost 200 attendees, drawn from all levels of government, research and academia, nonprofit organizations, International users and the private sector. This year’s theme is “Connecting the Pieces for Mitigation” which will elaborate on the changes that are Dear Friends, happening in the HAZUS-MH world! We will continue to explore the Comprehensive Data Management System (CDMS) and the two pilot states that have utilized the Web Portal as well as offer a CDMS training workshop On behalf of the State of North Carolina, it is a pleasure to extend warm greetings to for participants. Innovative uses of HAZUS-MH within the four phases of emergency management will also be a rd 2 everyone attending the 3 Annual FEMA HAZUS Conference. It is my privilege to join 3 focus along with the HAZUS-MH program’s integration into Risk MAP and the concept of creating one seamless the citizens of our great state in recognizing and celebrating this event. program. This year we also have our very first Map Gallery solely for the HAZUS-MH Conference in order to share all of the great work that users have been doing. -

Publication 1

We Are FEMA Helping People Before, During, and After Disasters 2 Publication 1 Purpose Publication 1 (Pub 1) is our capstone doctrine. It helps us as Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) employees understand our role in the emergency management community and provides direction for how we conduct ourselves and make decisions each day. It explains: ▪ Who We Are: An understanding of our identity and foundational beliefs ▪ Why We Are Here: A story of pivotal moments in history that have built and shaped our Agency ▪ What We Face: How we manage unpredictable and ever-evolving threats and hazards ▪ What We Do: An explanation of how we help people before, during, and after disasters ▪ How We Do It: An understanding of the principles that guide the work we do The intent of our Pub 1 is to promote innovation, flexibility, and performance in We Are FEMA achieving our mission. It promotes unity of purpose, guides professional judgment, and enables each of us to fulfill our responsibilities. Audience This document is for every FEMA employee. Whether you have just joined us or have been with the Agency for many years, this document serves to remind us why we all choose to be a part of the FEMA family. Our organization includes many different offices, programs, and roles that are all committed to helping people. Everyone plays a role in achieving our mission. We also invite and welcome the whole community to read Pub 1 to help individuals and organizations across the Nation better understand FEMA’s mission and role as we work together to carry out an effective system of emergency management. -

EASTERN 2021 FOOTBALL FCS Playoffs 1985•1992•1997•2004•2005•2007•2009•2010•2012•2013•2014•2016•2018•2020/21

EASTERN 2021 FOOTBALL FCS Playoffs 1985•1992•1997•2004•2005•2007•2009•2010•2012•2013•2014•2016•2018•2020/21 NCAA Championship Subdivision Honors (formerly I-AA) Bowl/All-Star Games 2018 (2019 NFLPA Collegiate Bowl) - Josh Lewis, CB Receiver Trio Combines for 817 catches and 132 TDs 2018 (2019 NFLPA Collegiate Bowl) - Jay-Tee Tiuli, DL he trio of SHAQ HILL, KENDRICK BOURNE and COOPER KUPP combined 2017 (2018 NFLPA Collegiate Bowl) - Jordan Dascalo, P for 817 catches for 12,412 yards and 132 touchdowns in 160 games played 2016 (2017 Senior Bowl) - Cooper Kupp, Wide Receiver T 2016 (2017 NFLPA Collegiate Bowl) - Samson Ebukam, DE (109 starts) during their careers which all ended in 2016. All three earned All-America 2016 (2017 NFLPA Collegiate Bowl) - Kendrick Bourne, WR honors as seniors (Kupp was a four-time consensus first team All-American) and 2015 (2016 NFLPA Collegiate Bowl) - Clay DeBord, OT combined for a total of 13 season-ending All-Big Sky Conference accolades during 2015 (2016 NFLPA Collegiate Bowl) - Aaron Neary, OG their careers. 2014 (2015 East West Shrine Game) - Tevin McDonald, With 211 career receptions for 3,130 yards and 27 touchdowns, Bourne finished his Safety career ranked in the top seven in all three categories in school history. He combined 2014 (2015 NFLPA Collegiate Bowl) - Jake Rodgers, OT with Kupp from 2013-16 for FCS records for combined catches (639) and reception 2013 (2014 NFLPA Collegiate Bowl) - T.J. Lee III, CB yards (9,594) by two players. 2012 (2013 Casino Del Sol Game) - Nicholas Edwards, WR 2011 (2012 NFLPA Collegiate Bowl) - Bo Levi Mitchell, QB Hill finished with 178 career catches to rank eighth in school history, good for 2,818 2011 (2012 Players All-Star Classic) - Renard Williams, DL yards (seventh) and 32 touchdowns (fifth). -

The Future of Earthquake Safety in the US

Risk Communication, Building Codes, and Consequences: The Future of Earthquake Safety in the U.S. WSSPC Annual Conference With the International Code Council September 30-October 3, 2007 Grand Sierra Resort Reno, Nevada FINAL TECHNICAL REPORT AWARD No. 07HQGR0076 Table of Contents Reno/Hotel Grand Sierra Resort Meeting Room Directory Crystal Ballroom Grand Ballroom Mezzanine Meeting Rooms Nevada Conference and Exhibition Center Silver State Pavilion Summit Pavilion Grand Sierra Resort Restaurants About Reno Program Conference Summary Schedule Abstracts Awards Summary of 2007 Awards Presentation Lifetime Achievement Award in Earthquake Risk Reduction to Richard K. Eisner Hawaii State Earthquake Advisory Committee, Hawaii State Civil Defense, and Hawaii Coastal Zone Management Program Pacific Tsunami Museum Lincoln County School District Oregon Natural Hazards Workgroup Utah Geological Survey/ WSSPC Basin & Range Province Committee Participants Conference Registrants as of September 21, 2007 WSSPC WSSPC Meeting Schedule Basin & Range Province Committee Meeting Agendas WSSPC Board Meeting Agenda WSSPC Annual Business Meeting Agenda Seismic Councils and Commissions Meeting Agenda WSSPC Board Meeting Minutes June 5, 2007 WSSPC Annual Business Meeting Minutes April 17, 2006 Executive Director Report – FEMA Semi-Annual Report #2 WSSPC FY 06-07 Income & Expense Statement FEMA Grant 2006 Income & Expense Statement USGS Grant 2007 Income & Expense Statement 2008 National Earthquake Conference Program History of Policy Recommendation Adoption Draft Policy Recommendation 07-1 & 07-2 Draft Policy Recommendation 07-3 Draft Policy Recommendation 07-4 Draft Policy Recommendation 07-5 Draft Policy Recommendation 07-6 Policy Recommendation 04-6 Policy Recommendation 04-7 Policy Recommendation 05-1 Policy Recommendation 05-2 Policy Recommendation 05-3 Policy Recommendation 06-1 WSSPC Bylaws Acknowledgments The idea to hold the WSSPC annual conference with the International Code Council (ICC) this year was suggested by Ron Lynn, Affiliate member of WSSPC and Board member of ICC. -

State Executive Branch 412 Nebraska State Government Judicial Commission Public Service

N ebraska s tate Gover NmeNt 411 State executive Branch Nebraska State Government Organization — Executive Branch1 412 Legislative Executive Judicial N ebraska Elected Officials Elected Officials s tate Auditor of Board of Regents Secretary Attorney Lieutenant Public Treasurer Board of of the University of Public Service G of State General* Governor** Governor Education Commission Accounts Nebraska over N Appointed Officials Appointed Officials me N t Direct Authority Other Agencies NOT Subject Agencies Subject to to Governor’s Indirect Authority Governor’s Direct Control Direct Control (Code Agencies) (Noncode Agencies) Other Boards, Commissions, Committees and Authorities * Department of Justice. ** Lieutenant governor selected by the governor as part of the election process 1 Source: Governor’s Policy Research Office. N ebraska s tate Gover NmeNt 413 State executive Branch1 The executive branch of Nebraska’s state government has six officers, several departments and other governmental agencies and bodies. Executive officers authorized by the state constitution, Article IV, Section 1, are the governor, lieutenant governor, secretary of state, auditor of public accounts, treasurer and attorney general. Other elected executive officials are the members of the State Board of Education, the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska, and the Public Service Commission. Executive officers are elected by popular vote to four-year terms, except the lieu- tenant governor, who is appointed by the governor as part of the election process. The governor and treasurer may serve only two consecutive terms; other executive officers may serve an unlimited number of terms. The executive branch has departments, agencies, boards, commissions, committees, councils, authorities and other governmental bodies. -

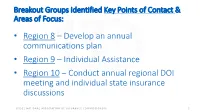

Develop an Annual Communications Plan • Region 9 – Individual Assistance • Region 10 – Conduct Annual Regional DOI Meeting and Individual State Insurance Discussions

Breakout Groups Identified Key Points of Contact & Areas of Focus: • Region 8 – Develop an annual communications plan • Region 9 – Individual Assistance • Region 10 – Conduct annual regional DOI meeting and individual state insurance discussions ©2021 NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF INSURANCE COMMISSIONERS 2 February 11 Time (Eastern) Topic Moderator 1:00pm – 1:05pm Welcome and Agenda Overview Jeff Czajkowski 1:05pm – 1:25pm Leadership Remarks Jeff Czajkowski Jeffrey Jackson, Assistant Administrator, Federal Insurance, FEMA 1:25pm – 2:10pm Resilience Priorities for 2021 Jeff Czajkowski NAIC Committee Activities – Jennifer Gardner & Aaron Brandenburg • Climate Taskforce • Private Flood BRIC Overview – Camille Crain 2:10pm – 2:20pm BREAK 2:20pm – 3:05pm Perils Conversation Part 1: Flood Region 8: What are we doing currently, what are the key issues and what Diana Herrera gaps can we identify? Discussion topics include: Jeff Herd • Insurance o NFIP Definition of Flood including Tsunami – Diana Herrera o Bundle 1 Rulemaking Review – Bartees Cox • Messaging: Spring Runoff & Hawaii Hurricane – Butch Kinerney & Olivia Humilde • Mitigation o Flood Mitigation Assistance – Jeff Herd o Increased Cost of Compliance – Diana Herrera o Private Flood – Diana Herrera • Section 1206 DRRA – Matt Buddie • Flood in Progress – Bartees Cox ©2021 NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF INSURANCE COMMISSIONERS 3 3:50pm – 4:00pm BREAK 4:00pm – 4:45pm Perils Conversation Part 3: Earthquakes Region 10: What are we doing currently, what are the key issues and what Scott Van Hoff gaps can -

California Insurance Company

1 Jerry Flanagan (SBN 271272) 2 [email protected] Benjamin Powell (SBN 311624) 3 [email protected] CONSUMER WATCHDOG 4 6330 San Vicente Blvd., Suite 250 Los Angeles, CA 90048 5 Tel: (310) 392-0522 6 Fax: (310) 392-8874 7 Kelly Aviles (SBN 257168) [email protected] 8 LAW OFFICES OF KELLY AVILES 9 1502 Foothill Blvd., Suite 103-140 La Verne, CA 91750 10 Tel: (909) 991-7560 Fax: (909) 991-7594 11 Attorneys for Petitioner/Plaintiff 12 13 14 15 SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA 16 FOR THE COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES 17 18 CONSUMER WATCHDOG, a non-profit CASE NO. organization, 19 VERIFIED PETITION FOR WRIT OF MANDATE AND COMPLAINT FOR 20 Petitioner/Plaintiff, DECLARATORY RELIEF 21 v. (Code Civ. Proc. §§ 1060, 1085; Public Records 22 Act, Gov. Code § 6250 et seq.) 23 RICARDO LARA, in his official capacity as the Insurance Commissioner of the State of 24 California; CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF 25 INSURANCE; and DOES 1–50, 26 Respondents/Defendants. 27 28 VERIFIED PETITION FOR WRIT OF MANDATE AND COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY RELIEF 1 Petitioner/Plaintiff Consumer Watchdog alleges as follows: 2 INTRODUCTION 3 1. This Petition and Complaint challenges the validity of California Insurance Commissioner 4 Ricardo Lara, who is sued here in his official capacity, and the California Department of Insurance’s 5 refusal to provide certain records in response to two California Public Records Act requests (Government 6 Code section 6250 et seq. (“PRA”)) submitted by Consumer Watchdog. 7 2. The Department of Insurance is the nation’s largest state regulatory agency. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 117 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 117 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 167 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, JUNE 17, 2021 No. 106 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. and was We pray this, having each been made Congratulations, Consul General called to order by the Speaker pro tem- free in Your name. Alicia Kerber, the first woman to head pore (Ms. DEGETTE). Amen. the consulate’s office in Houston. A f f good neighbor, we have worked to- gether on food drives, COVID testing THE JOURNAL DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER and vaccines, trade, and immigration PRO TEMPORE The SPEAKER pro tempore. Pursu- rights. The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- ant to section 11(a) of House Resolu- Tomorrow, June 18, the consulate fore the House the following commu- tion 188, the Journal of the last day’s will be opening its new headquarters. nication from the Speaker: proceedings is approved. Congratulations to the Mexican diplo- f WASHINGTON, DC, matic mission in Houston. May we con- June 17, 2021. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE tinue to work together the next 100 I hereby appoint the Honorable DIANA years. The SPEAKER pro tempore. Will the DEGETTE to act as Speaker pro tempore on Congratulations. Felicidades. gentleman from Pennsylvania (Mr. this day. f NANCY PELOSI, KELLER) come forward and lead the Speaker of the House of Representatives. House in the Pledge of Allegiance. HONORING THE LIFE AND SERVICE Mr. KELLER led the Pledge of Alle- f OF BARBARA MORRIS STAFFORD giance as follows: (Mr. -

3–17–08 Vol. 73 No. 52 Monday Mar. 17, 2008 Pages 14153–14370

3–17–08 Monday Vol. 73 No. 52 Mar. 17, 2008 Pages 14153–14370 VerDate Aug 31 2005 17:34 Mar 14, 2008 Jkt 214001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\17MRWS.LOC 17MRWS rwilkins on PROD1PC63 with PROPOSALS II Federal Register / Vol. 73, No. 52 / Monday, March 17, 2008 The FEDERAL REGISTER (ISSN 0097–6326) is published daily, SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Monday through Friday, except official holidays, by the Office PUBLIC of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Register Subscriptions: Act (44 U.S.C. Ch. 15) and the regulations of the Administrative Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Committee of the Federal Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Assistance with public subscriptions 202–512–1806 Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 is the exclusive distributor of the official General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 edition. Periodicals postage is paid at Washington, DC. Single copies/back copies: The FEDERAL REGISTER provides a uniform system for making Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Assistance with public single copies 1–866–512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and (Toll-Free) Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general FEDERAL AGENCIES applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published Subscriptions: by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public interest. Paper or fiche 202–741–6005 Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions 202–741–6005 Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the issuing agency requests earlier filing. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Jackie\My Documents\AA News & Views\AA

Vol. 17, No. 4 August 2005 ASSOCIATION OF STATE FLOODPLAIN MANAGERS, INC. ANNUAL CONFERENCE BIGGER, BROADER, BETTER The Association of State Floodplain Managers’ 29th annual conference was held June 12-17, 2005, in Madison, Wisconsin, also the site of the ASFPM’s first national conference (in 1982). This time, almost 950 participants from around the United States and the world attended (compared to just under 150 at the inaugural meeting). The 2005 conference showed not only that the enthusiasm and dedication of the floodplain management community has become even stronger over the years, but also that the field itself has broadened and deepened considerably. The week overflowed with expert technical presentations, small-group discussions, training sessions, technical field trips, and exhibits. The opening plenary session set the theme for the whole conference: “No Adverse Impact—Partnering for Sustainable Floodplain Management.” Chad Berginnis, Ohio Department of Natural Resources and Chair of the ASFPM, explained how local handling of extreme natural events (like floods) requires both cooperation among diverse partners in the public and private sector and looking ahead to anticipate future development and related problems. Steve Fontana, State Representative from Connecticut, relayed the process of self-education, coalition-building, and perseverance that he endured over the past few years in getting “no adverse impact” legislation passed in his state. Meg Galloway, President of the Association of State Dam Safety Officials, described the interactions—both in Wisconsin and nationally—among floodplain management and dam safety initiatives and programs. Welcome updates on the programs of three key federal partners were offered at the second plenary session.