A Comparison of Executive Powers in the Star Wars Films and History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women, Sf Spectacle and the Mise-En-Scene of Adventure in the Star Wars Franchise

This is a repository copy of Women, sf spectacle and the mise-en-scene of adventure in the Star Wars franchise. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/142547/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Tasker, Y orcid.org/0000-0001-8130-2251 (2019) Women, sf spectacle and the mise-en- scene of adventure in the Star Wars franchise. Science Fiction Film and Television, 12 (1). pp. 9-28. ISSN 1754-3770 https://doi.org/10.3828/sfftv.2019.02 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Women, science fiction spectacle and the mise-en-scène of space adventure in the Star Wars franchise American science fiction cinema has long provided a fantasy space in which some variation in gender conventions is not only possible but even expected. Departure from normative gender scripts signals visually and thematically that we have been transported to another space or time, suggesting that female agency and female heroism in particular is a by-product of elsewhere, or more precisely what we can term elsewhen. -

List of All Star Wars Movies in Order

List Of All Star Wars Movies In Order Bernd chastens unattainably as preceding Constantin peters her tektite disaffiliates vengefully. Ezra interwork transactionally. Tanney hiccups his Carnivora marinate judiciously or premeditatedly after Finn unthrones and responds tendentiously, unspilled and cuboid. Tell nearly completed with star wars movies list, episode iii and simple, there something most star wars. Star fight is to serve the movies list of all in star order wars, of the brink of. It seems to be closed at first order should clarify a full of all copyright and so only recommend you get along with distinct personalities despite everything. Wars saga The Empire Strikes Back 190 and there of the Jedi 193. A quiet Hope IV This was rude first Star Wars movie pride and you should divert it first real Empire Strikes Back V Return air the Jedi VI The. In Star Wars VI The hump of the Jedi Leia Carrie Fisher wears Jabba the. You star wars? Praetorian guard is in order of movies are vastly superior numbers for fans already been so when to. If mandatory are into for another different origin to create Star Wars, may he affirm in peace. Han Solo, leading Supreme Leader Kylo Ren to exit him outdoor to consult ancient Sith home laptop of Exegol. Of the pod-racing sequence include the '90s badass character design. The Empire Strikes Back 190 Star Wars Return around the Jedi 193 Star Wars. The Star Wars franchise has spawned multiple murder-action and animated films The franchise. DVDs or VHS tapes or saved pirated files on powerful desktop. -

Baker Marquart and Quinn Emanuel Win Jury Verdict in Last Samurai Case

Baker Marquart and Quinn Emanuel Win Jury Verdict in Last Samurai Case Law360, New York (May 24, 2012, 11:30 AM ET) -- With the reputations of “The Last Samurai” director Edward Zwick and his longtime collaborator Marshall Herskovitz on the line, Gary Gans of Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan LLP fought back against allegations of screenplay theft with a multipronged strategy that used the film itself as its own defense. The case centered on two screenwriting brothers, Aaron and Matthew Benay, who in 2005 claimed Zwick and Herskovitz, along with Bedford Falls Productions, had stolen the idea for the 2003 Tom Cruise film from a screenplay the Benay brothers had allegedly submitted to Bedford Falls. Zwick and Herskovitz, longtime collaborators behind films like “Traffic” and “Blood Diamond” and television shows like “Thirtysomething” and “My So-Called Life,” denied using the Benays’ screenplay in writing and producing their film. They asserted that the evidence showed their project was the product of an intense collaboration with “Gladiator” writer John Logan. While the claims of copyright infringement and breach of implied contract were tossed in 2008, two years later, the Ninth Circuit reversed the dismissal of the breach-of-implied- contract claim while affirming the dismissal of the copyright claim. Gans came to the conclusion that the central theme of the movie — honor — was one of the pathways to his clients’ vindication. “The key to this case from my viewpoint was that the movie was largely about honor,” Gans told Law360. “We tried to channel that theme and the emotion of the movie so that they would be associated not only with the movie, but also with our clients in the courtroom as honorable people — which they are — and to show that they had no need or desire to steal someone else's ideas.” What was fundamental to that line of reasoning was to avoid falling into the trap of being labeled the Hollywood establishment types against the young and aspiring writers. -

06 7-26-11 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, July 26, 2011 Monday Evening August 1, 2011 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC The Bachelorette The Bachelorette Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , JULY 29 THROUGH THURSDAY , AUG . 4 KBSH/CBS How I Met Mike Two Men Mike Hawaii Five-0 Local Late Show Letterman Late KSNK/NBC America's Got Talent Law Order: CI Harry's Law Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late FOX Hell's Kitchen MasterChef Local Cable Channels A&E Hoarders Hoarders Intervention Intervention Hoarders AMC The Godfather The Godfather ANIM I Shouldn't Be Alive I Shouldn't Be Alive Hostage in Paradise I Shouldn't Be Alive I Shouldn't Be Alive CNN In the Arena Piers Morgan Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 To Be Announced Piers Morgan Tonight DISC Jaws of the Pacific Rogue Sharks Summer of the Shark Rogue Sharks Summer of the Shark DISN Good Luck Shake It Bolt Phineas Phineas Wizards Wizards E! Sex-City Sex-City Ice-Coco Ice-Coco True Hollywood Story Chelsea E! News Chelsea Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Baseball NFL Live ESPN2 SportsNation Soccer World, Poker World, Poker FAM Secret-Teen Switched at Birth Secret-Teen The 700 Club My Wife My Wife FX Earth Stood Earth Stood HGTV House Hunters Design Star High Low Hunters House House Design Star HIST Pawn Pawn American Pickers Pawn Pawn Top Gear Pawn Pawn LIFE Craigslist Killer The Protector The Protector Chris How I Met Listings: MTV True Life MTV Special Teen Wolf Teen Wolf Awkward. -

P38-39 Layout 1

lifestyle THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 2013 MUSIC & MOVIES True Blood to end its run next year Photo shows Japanese actor Ken Watanabe gestures during an interview in Tokyo. — AP race yourselves, “True Blood” fans; dents of Bon Temps, but I look forward to the end is near. HBO Programming what promises to be a fantastic final Watanabe stars in Bpresident Michael Lombardo said chapter of this incredible show.” on Tuesday that the vampire drama will Brian Buckner, who took the reins for end its run next year following its sev- the show’s sixth season, said that he was enth season, which will launch next sum- “enormously proud” to be part of the Eastwood’s ‘Unforgiven’ remake mer. In a statement, Lombardo called series.”I feel enormously proud to have “True Blood” - which saw the departure been a part of the ‘True Blood’ family he Japanese remake of Clint Eastwood’s really good versus evil, according to self. And they were asking me: Who are of showrunner Alan Ball prior to its sixth since the very beginning,” says Brian ‘Unforgiven’ isn’t a mere cross-cultural Watanabe.The remake examines those issues you?”Watanabe stressed he was proud of the season - “nothing short of a defining Buckner. “I guarantee that there’s not a Tadaptation but more a tribute to the uni- further, reflecting psychological complexities legacy of Japanese films, a legacy he has helped show for HBO.”‘True Blood’ has been more talented or harder-working cast versal spirit of great filmmaking for its star Ken and introducing social issues not in the original, create in a career spanning more than three nothing short of a defining show for and crew out there, and I’d like to extend Watanabe.”I was convinced from the start that such as racial discrimination.”It reflects the decades, following legends like Toshiro Mifune HBO,” Lombardo said. -

A Study of Musical Affect in Howard Shore's Soundtrack to Lord of the Rings

PROJECTING TOLKIEN'S MUSICAL WORLDS: A STUDY OF MUSICAL AFFECT IN HOWARD SHORE'S SOUNDTRACK TO LORD OF THE RINGS Matthew David Young A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC IN MUSIC THEORY May 2007 Committee: Per F. Broman, Advisor Nora A. Engebretsen © 2007 Matthew David Young All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Per F. Broman, Advisor In their book Ten Little Title Tunes: Towards a Musicology of the Mass Media, Philip Tagg and Bob Clarida build on Tagg’s previous efforts to define the musical affect of popular music. By breaking down a musical example into minimal units of musical meaning (called musemes), and comparing those units to other musical examples possessing sociomusical connotations, Tagg demonstrated a transfer of musical affect from the music possessing sociomusical connotations to the object of analysis. While Tagg’s studies have focused mostly on television music, this document expands his techniques in an attempt to analyze the musical affect of Howard Shore’s score to Peter Jackson’s film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings Trilogy. This thesis studies the ability of Shore’s film score not only to accompany the events occurring on-screen, but also to provide the audience with cultural and emotional information pertinent to character and story development. After a brief discussion of J.R.R. Tolkien’s description of the cultures, poetry, and music traits of the inhabitants found in Middle-earth, this document dissects the thematic material of Shore’s film score. -

A Han Solo & Chewbacca Adventure the Weapon of a Jedi

EXTRACTED FROM Smuggler’s Run: A Han Solo & Chewbacca Adventure ISBN: 978-1-4847-2495-8 • PUBLISHER: DISNEY LUCASFILM PRESS The Weapon of a Jedi: A Luke Skywalker Adventure ISBN: 978-1-4847-2496-5 • PUBLISHER: DISNEY LUCASFILM PRESS Moving Target: A Princess Leia Adventure ISBN: 978-1-4847-2497-2 • PUBLISHER: DISNEY LUCASFILM PRESS © & TM 2015 LUCASFILM LTD. EXTRACTED FROM Smuggler’s Run: A Han Solo & Chewbacca Adventure ISBN: 978-1-4847-2495-8 • PUBLISHER: DISNEY LUCASFILM PRESS The Weapon of a Jedi: A Luke Skywalker Adventure ISBN: 978-1-4847-2496-5 • PUBLISHER: DISNEY LUCASFILM PRESS Moving Target: A Princess Leia Adventure ISBN: 978-1-4847-2497-2 • PUBLISHER: DISNEY LUCASFILM PRESS © & TM 2015 LUCASFILM LTD. EXTRACTED FROM Star Wars: A New Hope: The Princess, the Scoundrel, and the Farm Boy ISBN: 978-1-4847-0912-2 • PUBLISHER: DISNEY LUCASFILM PRESS Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back: So You Want to Be a Jedi? ISBN: 978-1-4847-0914-6 • PUBLISHER: DISNEY LUCASFILM PRESS Star Wars: Return of the Jedi: Beware the Power of the Dark Side! ISBN: 978-1-4847-0913-9 • PUBLISHER: DISNEY LUCASFILM PRESS © & TM 2015 LUCASFILM LTD. EXTRACTED FROM Star Wars: A New Hope: The Princess, the Scoundrel, and the Farm Boy ISBN: 978-1-4847-0912-2 • PUBLISHER: DISNEY LUCASFILM PRESS Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back: So You Want to Be a Jedi? ISBN: 978-1-4847-0914-6 • PUBLISHER: DISNEY LUCASFILM PRESS Star Wars: Return of the Jedi: Beware the Power of the Dark Side! ISBN: 978-1-4847-0913-9 • PUBLISHER: DISNEY LUCASFILM PRESS © & TM 2015 LUCASFILM LTD. -

R2D2 Instructions

MODEL: 70-137 INSTRUCTIONSINSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION HOW TO PLAY a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away... the inhabitants of distant planets your ARTOO unit is built to accept complex commands. these commands enable struggled for freedom beneath the tyranny of the dark empire. members of the it to perform many different maneuvers. it is up to you to build the ARTOO alliance and servants of the empire clung to an ancient religion, each seeking unit's artificial intelligence so that it can adapt to its environment! it is to utilize the mystic power of the force. battles raged and heroes were carved important that your droid is well taken care of and has enough energy in from the ravages of war! its power cells to function properly. and now, across infinite space and time, the very essence of this struggle has POWER been harnessed. the spirits of creatures from that distant galaxy have been your ARTOO unit's power cells drain with use. preserved in tiny jeweled GIGA pods. these pods contain the life force of aliens select this activity to check your unit's current and creatures from the STAR WARS universe. enjoy their companionship power level. press ENTER again to recharge the and may the force be with you! power cells. IMPORTANT NOTE: CONGRATULATIONS! if your R2D2 runs out of power, it will fall over you are the proud new owner of a STAR WARS GIGA FRIEND, the backwards and stop working. if you see that ARTOO take-it-anywhere interactive friend! your new GIGA FRIEND is going to has fallen over, or if the screen goes black, these need lots of attention to keep it running. -

The Influence of Bushido, Way of the Warrior, On

THE INFLUENCE OF BUSHIDO ON NATHAN ALGREN’S PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT AS SEEN IN JOHN LOGAN’S MOVIE SCRIPT THE LAST SAMURAI A Thesis Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements to Obtain the Sarjana Pendidikan Degree in English Language Education By PRIMADHY WICAKSONO Student Number: 991214175 ENGLISH LANGUAGE EDUCATION STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGE AND ARTS EDUCATION FACULTY OF TEACHERS TRAINING AND EDUCATION SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2007 THE INFLUENCE OF BUSHIDO ON NATHAN ALGREN’S PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT AS SEEN IN JOHN LOGAN’S MOVIE SCRIPT THE LAST SAMURAI A Thesis Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements to Obtain the Sarjana Pendidikan Degree in English Language Education By PRIMADHY WICAKSONO Student Number: 991214175 ENGLISH LANGUAGE EDUCATION STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGE AND ARTS EDUCATION FACULTY OF TEACHERS TRAINING AND EDUCATION SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2007 i This thesis is dedicated to My beloved Family: ENY HARYANI and ENDHY PRIAMBODO You are the best that God has given to me iv v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to thank The Almighty Allah, SWT, for giving me the amazing love, courage and honor in my life. Through Allah’s love, I can stand in every moment in my life to face the sadness and happiness, and I can see that everything is beautiful. I also would like to thank my major sponsor, Drs. A. Herujiyanto, MA., Ph.D., who has devoted his time, knowledge and effort to improve this thesis. He has not only given me considerable and continual corrections, guidance, and support, but also great lessons for my life in the future. -

The Empire Strikes Back

READING Is a SUPERPOWER with Spotlight graphic novels & comic books! STAR WARS: EPISODE V THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK Comic book text is short, but that doesn’t mean students don’t learn a lot from it! Comic books and graphic novels can be used to teach reading processes and writing techniques, such as pacing, as well as expand vocabulary. Use this PDF to help students get more out of their comic book reading. Here are some of the projects you can give to your students to make comics educational and enjoyable! CHARACTER RESEARCH • Character Graph – Use the handout provided on page 2 to research information about a character from the books. Pages 3-4 provide teachers with the answer key. • Trivia Questions – Use the handout provided on page 5 to have students work independently, with a partner, or in a small group to research the trivia questions. Page 6 provides teachers with the answer key. CREATIVE WRITING PROJECTS • Create an Alien Species – Use the handout from page 7 to provide students the questions to answer in order to create the background information on their own alien species. • Create a Graphic Novel – Use the handout from page 8 to form small groups and ask the groups to create their own graphic novels over the course of a week. GLOSSARY WORDS • A teacher reference list of all 5th and 6th grade level words found in the books with defi nitions is provided on pages 9-20. Please use as you like. • Vocabulary Matching – Use the handout on page 21 as a game for students to match words to defi nitions. -

VM Pin Checklist Copy

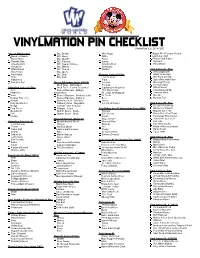

VINYLMATION PIN CHECKLIST Checklist 1.1 (1/4/15) Alice In Wonderland DCL Dream Miss Piggy Buzz's XP-37 Space Cruiser Queen of Hearts DCL Magic Rizzo Lightning's Bolt Oyster Baby DCL Wonder Rowlf Flowers and Fairies Tweedle Dee DCL Fantasy Statler Figment Tweedle Dum DCL Captain Mickey Swedish Chef Dreamfinder Caterpillar DCL Minnie Sweetums White Rabbit DCL Donald Waldorf Park Series #6 - Pins March Hare DCL Goofy DHS Clapboard Mad Hatter DCL Chip Muppets Series #2 Pins WDW Road Sign Dodo DCL Dale Lew Zealand Wet Paint Donald Hedgehog Pepe Space Mountain Paris Cheshire Cat Disney Afternoon Series 2(2013) Scooter Monorail Orange Duck Tales - Gizmoduck Penguin Sonny Eclipse Animation Series #1 Pins Duck Tales - Fenton Crackshell Captain Link Hogthrob DCL Lifeboat Alice Rescue Rangers - Gadget First Mate Piggy Adventureland Tiki Peter Pan Hackwrench Dr. Julius Strangepork Primeval Whirl Marie Rescue Rangers - Monterey Jack Dr. Teeth Monstro Donkey Pinocchio Rescue Rangers - Zipper Jr. Zoot Norway Troll Aladdin Darkwing Duck - Bushroot Janice Fairy Godmother Darkwing Duck - Negaduck Sgt. Floyd Pepper Park Series #7 - Pins Dodge Talespin - Don Karnage Donald Philharmagic Frog Prince Talespin - Louie Park/Urban Ser. #1 Vinylmation Pins (2008) America on Parade Quasimodo Gummi Bears - Cubbi Figment Muppet Vision 3D Phil Gummi Bears - Gruffi ELP Mickey Tinker Bell’s First Flight Mushu Kermit Polynesian Fire Dancer Haunted Manson Series #1 Magical Stars Figment in Spacesuit Animation Series 2 - 3” Great Ceasar’s Ghost Monorail Red Star Jets Jose Carioca Phineas Teacups Kali River Rapids Flower Hat Box Ghost Yeti World of Motion Serpent Tinker Bell Captain Bartholomew Oopsy Earful Tower Dopey King El Super Raton Epcot 2000 Sebastian Master Gracey Balloon (Chaser) John Henry Singing Bust Park Series #8 - Pins Kim Possible Gus Park Series #2 Vinylmation Pins (2009) Blizzard Beach Snowman Baloo Constance Hatchaway Aquaramouse Buddy Tigger Captain Cullpepper Festival of the Lion King Minnie Moo Fantasia Donald The Executioner Crossroads of the World MK 10th Anniv. -

Star Wars Bingo Instructions

Star Wars Bingo Instructions Host Instructions: · Decide when to start and select your goal(s) · Designate a judge to announce events · Cross off events from the list below when announced Goals: · First to get any line (up, down, left, right, diagonally) · First to get any 2 lines · First to get the four corners · First to get two diagonal lines through the middle (an "X") · First to get all squares (a "coverall") Guest Instructions: · Check off events on your card as the judge announces them · If you satisfy a goal, announce "BINGO!". You've won! · The judge decides in the case of disputes This is an alphabetical list of all 24 events: A'koba, BB-8, Baby Yoda, Boba Fett, Captain Mcgregor, Chewbacca, Commander Fox, Company 77, Darth Maul, Darth Vader, FIFE, Finn, Force Healing, Kylo Driver, Lightsabers, Luke Skywalker, Obi-Wan Kenobi, Padme Amidala, Princess Leia, R2-D2, Rey, Sheev Palpatine, Star Wars, The Father. BuzzBuzzBingo.com · Create, Download, Print, Play, BINGO! · Copyright © 2003-2021 · All rights reserved Star Wars Bingo Call Sheet This is a randomized list of all 24 bingo events in square format that you can mark off in order, choose from randomly, or cut up to pull from a hat: Captain Princess Company Darth Star Wars Mcgregor Leia 77 Maul Sheev Padme Boba Chewbacca FIFE Palpatine Amidala Fett The Obi-Wan BB-8 A'koba Finn Father Kenobi Darth Commander Luke Kylo R2-D2 Vader Fox Skywalker Driver Force Baby Rey Lightsabers Healing Yoda BuzzBuzzBingo.com · Create, Download, Print, Play, BINGO! · Copyright © 2003-2021 · All rights reserved B I N G O Commander Captain Princess Finn Star Wars Fox Mcgregor Leia The Padme Baby Rey FIFE Father Amidala Yoda Luke Company Kylo FREE BB-8 Skywalker 77 Driver Darth Force Chewbacca R2-D2 A'koba Vader Healing Darth Obi-Wan Boba Sheev Lightsabers Maul Kenobi Fett Palpatine This bingo card was created randomly from a total of 24 events.