• Articles • Across the Star Wars Universe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Connotations 14-01

Volume 14, Issue 1 February/March ConNotations 2004 The Bi-Monthly Science Fiction, Fantasy & Convention Newszine of the Central Arizona Speculative Fiction Society April Kicks Off with Ursula K Le Featured Inside Guin, Timothy Zahn, Phoenix SF Tube Talk Special Features ComicCon and World Horror All the latest news about Ursala K LeGuin by Lee Whiteside Scienc Fiction TV shows and other April Events by Lee Whiteside By Lee Whiteside The Arizona Book Festival on Saturday, outreach/scifisymp.html and http:// April 3rd, will feature authors Ursula K. Le www.asu.edu/english/events/outreach/ 24 Frames Jinxed, Hexed, or Cursed: Guin, Alan Dean Foster, and Diana leguin.html All the latest Movie News How I Ruined Harlan Ellison’s Gabaldon on the main stage with CASFS The next day is the Seventh Annual by Lee Whiteside Return to Arizona, Part 2 bringing in Timothy Zahn and other local Arizona Book Festival being held from 10 By Shane Shellenbarger authors for autographing and a special am to 5 pm at the Carnegie Center at 1100 Pro Notes block of programming. LeGuin will also be W. Washingtion in central Phoenix. The Waldorf Conference: appearing at ASU on Friday, April 2nd. Featured authors at the book festival are News about locl genre authors and fans Microphones, scripts, and actors The ASU Department of English Ron Carlson, Nancy Farmer, Alan Dean By Shane Shellenbarger Outreach will be hosting two events on Foster, Diana Gabaldon, Ursula K. Le Musical Notes Friday, April 2nd with Ursula K. LeGuin. Guin, Tom McGuane, and U.S. Supreme In Memorium First will be a daylong Symposium on the Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. -

Star Wars Fans Invade Ocean County Library

OCEAN COUNTY LIBRARY Connecting People … Building Community … Transforming Lives 101 Washington St., Toms River, NJ 08753-7625 Telephone: 732-349-6200 www.theoceancountylibrary.org Susan Quinn, Director Aug. 3, 2015 CONTACT: Sal Ottaviano, 7320349-6200, ext. 5905 [email protected] PRESS RELEASE Star Wars fans invade Ocean County Library TOMS RIVER – Star Wars fans of all ages met Darth Vader, stormtroopers and a young Obi Wan Kenobi from the popular science fiction saga Saturday at the Ocean County Library’s Beachwood branch at the “Star Wars Day” program. This was the first of two library events aimed at Star Wars fans featuring members of Vader’s 501st Legion, an Ocean County based Star Wars fan club. Members were dressed in highly detailed costumes from the film series. The group performs at conventions, libraries, and charities year round. Children and their parents came dressed in colorful T-shirts and costumes to meet the 501st Legion. Other Star Wars characters included a cloaked Jawa who posed for photos with fans during the event. Activities included galactic games and creating light sabers out of freezer pops and duct tape, so little Padawans could take the fun home. If you missed your chance to explore the galaxy, don’t worry. This program will be repeated at the Ocean County Library’s Little Egg Harbor branch at 6 p.m. Thursday, Aug. 20. The outdoor event will include crafts, games, alien face painting and a battlestar balloon game plus a return visit by the 501st Legion. Admission for the Little Egg Harbor branch “Star Wars Day” program is free but registration is required. -

Get the Celebration: Japan Schedule in PDF Format

exhibit UPDATED: 7/11/08 10:18 AM event panel REBELSCUM.COM party SATURDAY, SUNDAY, MONDAY, JULY 19-21: 10:00AM - 6:00PM meet/greet 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 2:00 2:30 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM SATURDAY (7/19/2008) Autograph Hall () Art Show () Exhibit Hall () Family Area () Lawrence Nobel sculpts Luke () Vader Project () Bounty in Japan – The Fetts (Main Stage) Jedi Training Stage () Meet the 501st Legion (Fan & Collectors’ Stage) 501st Legion Honorary Member: Tsuyoshi Nagano (Fan & Collectors’ Stage) Star Wars: The Clone Wars (Main Stage) Jedi Training Stage () Stormtrooper Costume Panel (Fan & Collectors’ Stage) Star Wars: The Clone Wars (Main Stage) Rebel Legion & Jedi Order on Stage () Sith Lord & Bounty Hunter Costume Panel (Fan & Collectors’ Stage) Modeling the Saga: Lorne Peterson (Main Stage) Prep of 501st Parade (501st Fan Table) Bootleg Star Wars: Shuichi Kimura & John Hallam (Fan & Collectors’ Stage) Free Autograph: Dave Filoni (Autograph Hall) 501st Parade () Jedi Training Stage () Japanese Star Wars Posters: Hideyuki Takizawa (Fan & Collectors’ Stage) Skywalking with Mark Hamill (Main Stage) Jedi Training Stage () Star Wars Collectibles Road Show (Fan & Collectors’ Stage) World Premiere: Star Warriors (Main Stage) Jedi Training Stage () Rare & Unusual Japanese Collectibles: Yu Katagiri (Fan & Collectors’ Stage) PAGE 1 exhibit -

An Ethnographic Study of Shared Information Practices in an Online Cosplay Community

“I found what I needed, which was a supportive community”: An ethnographic study of shared information practices in an online cosplay community 1 By Emily Vardell (ORCID: 0000-0002-3037-4789) 2 Ting Wang (ORCID: 0000-0002-1423-4559) 3 Paul Thomas (ORCID: 0000-0002-5596-7951) Scheduled to be published as: Vardell, E., Wang, T., & Thomas, P. (2021). “I found what I needed, which was a supportive community”: An ethnographic study of shared information practices in an online cosplay community. Journal of Documentation. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-02-2021-0034 Abstract Purpose – This study explored the information practices of cosplayers, as well as the social norms, social types, and information infrastructure of an online cosplay Facebook group, the Rey Cosplay Community (RCC). Design/methodology/approach – To better understand individual behavior, the authors made use of ethnographic methods and semi-structured interviews. Observation of the RCC was combined with information gleaned from select participant interviews. Findings – The results suggest that the RCC can be conceived of as an information community where fans obtain and share information about cosplay costume making. Sufficient and well-organized information and positive community culture greatly help community members make their costumes. Originality/value – This works serves as a bridge between fan studies and information science research in its exploration of online communities, shared information practices, and creating non-toxic virtual environments. It also lends support to the idea that positivity, respect for community rules, and a tight-knit connection between members play essential roles in building a non-toxic fan and information community. -

Rpggamer.Org (Characters D6 / Dogma (Clone Trooper)) Printer

Characters D6 / Dogma (Clone Trooper) Name: Dogma Homeworld: Kamino Species: Human (clone) Gender: Male Height: 1.83 meters Hair color: Black Eye color: Brown Skin color: Tan Dex: 3D Blaster: 6D Dodge: 6D Brawling Parry: 5D Grenade: 4D Missile Weapons: 3D+2 Thrown Weapons: 4D+2 Vehicle Blasters: 5D Perc: 3D Command: 4D+1 Search: 4D+2 Sneak: 4D Str: 3D Brawling: 6D Know: 3D Tactics: 4D Mech: 3D Repulsorlift Operation: 4D Tech: 3D Blaster Repair: 4D+1 First Aid: 4D Move: 10 (9) Force Sensitive: No Force Points: 1 Dark Side Points: 0 Character Points: 3 Equipment: Phase 2 CloneTrooper Armour (+2D Physical, +1D Energy, -1D Dexterity, -1 Move) DC-15 Blaster Rifle (Damage: 5D (normal), 5D+2 (high power setting)) Utility Belt, Comlink, Grenades (5D/4D/3D) Description: "Dogma" was the nickname of a clone trooper who served in the 501st Legion of the Grand Army of the Republic during the Clone Wars. He was known to always follow orders. After being manipulated by Jedi Master and secret Separatist agent Pong Krell during the Battle of Umbara, Dogma executed Krell to prevent him from revealing Republic military secrets. Biography Around 20 BBY, Dogma was sent along with the 501st Legion to retake the planet Umbara, whose native species had sided with the Confederacy of Independent Systems. During the invasion, the republic forces were able to land, while suffering heavy casualties. Dogma and the 501st were commanded by General Anakin Skywalker and Captain Rex. Dogma, however, was only interested in completing the mission. However, after the 501st Legion had established a foothold in Umbaran soil and was permitted some time to rest, command was transferred from General Skywalker to General Pong Krell, because Skywalker was called back to Coruscant at the request of both the Supreme Chancellor and the Jedi Council. -

Dark Matter #4

Cover Page DarkIssue Four Matter July 2011 SF, Fantasy & Art [email protected] Dark Matter Issue Four July 2011 SF, Fantasy & Art [email protected] Dark Matter Contents: Issue 4 Dark Matter Stuff 1 News & Articles 7 Gun Laws & Cosplay 7 Troopertrek 2011 8 Hugo Award Nominees 10 2010 Aurealis Awards 14 2011 Aurealis Awards to be held in Sydney again 15 2011 Ditmar Awards 16 2011 Chronos Awards 20 Renovation WorldCon 22 Iron Sky update 28 Art by Ben Grimshaw 30 Ebony Rattle as Electra, Art by Ben Grimshaw 31 The Girl in the Red Hood is Back … But She’s a Little Different 32 Launching & Gaining Velocity 34 Geek and Nerd 35 Peacemaker - A Comic Book 36 Continuum 7 Report 38 Starcraft 2 - Prae.ThorZain 46 Good Friday Appeal 50 FAQ about the writing of Machine Man, by Max Barry 65 J. Michael Straczynski says... 67 Interviews 69 Kevin J. Anderson talks to Dark Matter 69 Tom Taylor and Colin Wilson talk to Dark Matter 78 Simon Morden talks to Dark Matter 106 Paul Bedford talks to Dark Matter 115 Cathy Larsen talks to Dark Matter 131 Madeleine Roux talks to Daniel Haynes 142 Chewbacca is Coming 146 Greg Gates talks to Dark Matter 153 Richard Harland talks to Dark Matter 165 Letters 173 Anime/Animation 176 The Sacred Blacksmith Collection 176 Summer Wars 177 Evangelion 1.11 You are [not] alone 178 Evangelion 2.22 You can [not] advance 179 Book Reviews 180 The Razor Gate 180 Angelica 181 2 issue four The Map of Time 182 Die for Me 183 The Gathering 184 The Undivided 186 the twilight saga: the official illustrated guide 188 Rivers -

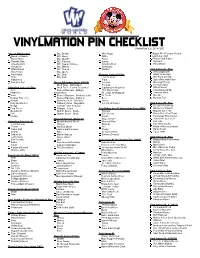

VM Pin Checklist Copy

VINYLMATION PIN CHECKLIST Checklist 1.1 (1/4/15) Alice In Wonderland DCL Dream Miss Piggy Buzz's XP-37 Space Cruiser Queen of Hearts DCL Magic Rizzo Lightning's Bolt Oyster Baby DCL Wonder Rowlf Flowers and Fairies Tweedle Dee DCL Fantasy Statler Figment Tweedle Dum DCL Captain Mickey Swedish Chef Dreamfinder Caterpillar DCL Minnie Sweetums White Rabbit DCL Donald Waldorf Park Series #6 - Pins March Hare DCL Goofy DHS Clapboard Mad Hatter DCL Chip Muppets Series #2 Pins WDW Road Sign Dodo DCL Dale Lew Zealand Wet Paint Donald Hedgehog Pepe Space Mountain Paris Cheshire Cat Disney Afternoon Series 2(2013) Scooter Monorail Orange Duck Tales - Gizmoduck Penguin Sonny Eclipse Animation Series #1 Pins Duck Tales - Fenton Crackshell Captain Link Hogthrob DCL Lifeboat Alice Rescue Rangers - Gadget First Mate Piggy Adventureland Tiki Peter Pan Hackwrench Dr. Julius Strangepork Primeval Whirl Marie Rescue Rangers - Monterey Jack Dr. Teeth Monstro Donkey Pinocchio Rescue Rangers - Zipper Jr. Zoot Norway Troll Aladdin Darkwing Duck - Bushroot Janice Fairy Godmother Darkwing Duck - Negaduck Sgt. Floyd Pepper Park Series #7 - Pins Dodge Talespin - Don Karnage Donald Philharmagic Frog Prince Talespin - Louie Park/Urban Ser. #1 Vinylmation Pins (2008) America on Parade Quasimodo Gummi Bears - Cubbi Figment Muppet Vision 3D Phil Gummi Bears - Gruffi ELP Mickey Tinker Bell’s First Flight Mushu Kermit Polynesian Fire Dancer Haunted Manson Series #1 Magical Stars Figment in Spacesuit Animation Series 2 - 3” Great Ceasar’s Ghost Monorail Red Star Jets Jose Carioca Phineas Teacups Kali River Rapids Flower Hat Box Ghost Yeti World of Motion Serpent Tinker Bell Captain Bartholomew Oopsy Earful Tower Dopey King El Super Raton Epcot 2000 Sebastian Master Gracey Balloon (Chaser) John Henry Singing Bust Park Series #8 - Pins Kim Possible Gus Park Series #2 Vinylmation Pins (2009) Blizzard Beach Snowman Baloo Constance Hatchaway Aquaramouse Buddy Tigger Captain Cullpepper Festival of the Lion King Minnie Moo Fantasia Donald The Executioner Crossroads of the World MK 10th Anniv. -

In the Workshop with Sidi Ren

Mandalorian Mercs ISSUE 13 CANON KITS How the Mercs are a little different. IRON CRUSADE The next installment. ORDER OF THE ORI’RAMIKAD The highest award in the club. IN THE WORKSHOP WITH SIDI REN The Mandalorian Mercs is a worldwide Star Wars costuming organization comprised of and operated by Star Wars fans and volunteers. It is the elite Mandalorian cos- tuming organization. Star Wars, its characters, costumes, and all associated items are the intellectual property of Lucasfilm. ©2016 Lucasfilm Ltd. & ™ All rights reserved. Used under authorization. welcome! Greetings members, friends, and fans, Talk about going out with a bang, that’s exactly how 2015 exited stage. Episode 7 has arrived, and with it a renewed interest in Star Wars world- wide. If you haven’t seen the movie yet, go see it. If you have seen it, go see it again! It’s worth a few watches before the pause before DVD/ Blue Ray release. Mandalorian Mercs members had the privilege of at- tending red-carpet premiers around the world, as well as helping raise interest through various TV and media outlets. As we go into 2016, we have some major milestones and goals ahead of us. Celebration London will be held in July, and our European Clans are already busy on getting MMCC’s on-site presence finalized and built. I don’t want to spoil anything, but if all goes as planned it should be an- other outstanding show under our belts. In January we’ll be kicking off a major global fund-raiser to undertake a project years in the making; MMCC Headquarters. -

Garrison Corellia Press Kit

Garrison Corellia Press Kit 501st Legion Garrison Corellia https://www.501st.com https://garrisoncorellia.com The 501st Legion is a worldwide Star Wars costuming organization comprised of and operated by Star Wars fans. While it is not sponsored by Lucasfilm Ltd., it follows generally accepted ground rules for Star Wars fan groups. Star Wars, its characters, costumes, and all associated items are the intellectual property of Lucasfilm. © & ™ Lucasfilm Ltd. All rights reserved. Used under authorization. ORGANIZATION BACKGRO UNDER Welcome to Garrison Corellia, the West Virginia “chapter” of the 501st Legion. The 501st Legion is a worldwide, professional costuming organization dedicated to the Dark Side characters of the Star Wars Universe. Over 13,000 members passionately recreate accurate costumes of the many iconic characters portrayed in movies, books, video games, comics, and TV shows. Garrison Corellia was created out of Garrison Carida, which was originally made up of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and West Virginia. Carida members from West Virginia created a small unit called Squad Corellia in December 2012. There were 10 founding members that met at a restaurant to discuss the creation of the Squad and decided the state was ready to strike out on its own. In November 2015, there were enough members to form a Garrison. As of 2018, the state group has more than 50 members stretching from the panhandles to the southern coalfields. Garrison Corellia is proud to participate in a wide array of charity and non-profit events throughout our state and within our local communities. Freely volunteering our time to help others while celebrating Star Wars, our members are always looking for opportunities to contribute, inspire and spread joy to the communities and state of West Virginia. -

Rebels Season 2 Sourcebook Version 1.0 March 2017

A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away... CREDITS I want to thank everyone who helped with this project. There were many people who helped with suggestions and editing and so many other things. To those I am grateful. Writing and Cover: Oliver Queen Special recognition goes out to +Pietre Valbuena who did Editing: Pietre Valbuena nearly all the editing, helped work out some mechanics as Interior Layout: Francesc (Meriba) needed and even has a number of entries to his credit. This book would not be anywhere near as good as it presently is without his involvement. The appearance of this book is credited to the skill of Francesc (Meriba). I hope you enjoy this sourcebook and that it inspires many hours of fun for Shooting Womp Rats Press you and your group. Star Wars Rebels Season 2 Sourcebook version 1.0 March 2017 May the Force be With You, Oliver Queen Table of contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................... 2 ENERGY WEAPONS .................................................. 88 CHAPTER 1: HEROES OF THE REBELLION .......... 4 Blasters .................................................................... 88 THE SPECTRES ............................................................. 4 Other weapons ...................................................... 91 “Spectre 1” Kanan Jarrus .......................................... 4 EXPLOSIVES AND ORDNANCE .......................... 92 “Spectre 2” Hera Syndulla ........................................ 7 MELEE WEAPONS .................................................. -

501St Legion Performance and Hospitality Rider Private Events

501st Legion Performance and Hospitality Rider Private Events The 501st Legion is an all-volunteer costume organization focused on professional costuming, spreading the love of Star Wars to fans around the globe, and to charity work on local, national, and world-wide levels. The 501st Legion cannot make a guarantee of our ability to provide specific characters, or numbers of personnel for any given event. All 501st Legion members make use of Lucasfilm LTD copyrights and trademarks with permission from Lucasfilm LTD and hold no ownership of these intellectual properties and cannot grant any rights to the same properties. All 501st Legion members will comport themselves with the highest standard of professional behavior. The Event Sponsor (hereafter referred to as “the Sponsor”) is the individual or group requesting an appearance by members of the Legion. Private Event Definition A private event is any event requested for a nonpublic or non-promotional function. Private events include (but are not limited to): birthday parties, weddings, award ceremonies, retirement parties, and hospital visits. It should be noted that the Legion does not participate in events which might be considered political or religious in nature. Corporate Event Requirements may be found here http://www.501st.com/databank/CorporateEventRider Charity Event Requirements may be found here http://www.501st.com/databank/CharityEventRider Character Compensation As a rule, the Legion and its members do not charge a fee for private appearances. However, a donation in the name of the Legion to a reputable charity commensurate with the number of characters requested and the event duration is greatly appreciated. -

FCC Ends “Net Neutrality”

DAVITA SETTLES KICKBACK CLAIMS FOR $63.7 MILLION »8A Voice of the Rocky Mountain Empire FRIDAY, DECEMBER 15, 2017 SUNNY AND WARMER E59° F33° »14A B © THE DENVER POST B $2 PRICE MAY VARY OUTSIDE METRO DENVER 66 FCCPARTY-LINE VOTE ends “net neutrality” Challenges could come from RUSSIA PROBE STAR WARS PREMIERE: “THE LAST JEDI” lawsuits, Congress By Barbara Ortutay Panel’s and Tali Arbel The Associated Press The Federal Communica- focus tions Commission repealed the Obama-era “net neutrali- ty” rules Thursday, giving in- turns to ternet service providers such as Verizon, Comcast and AT&T a free hand to slow or future block websites and apps as they see fit or charge more for By Mary Clare Jalonick faster speeds. The Associated Press In a straight party-line vote of 3-2, the Republican-con- WASHINGTON»With no firm trolled FCC junked the long- conclusions yet on whether time principle that said all web President Donald Trump’s traffic must be treated equally. campaign may have coordi- The move represents a radical nated with Russia, the Senate departure from more than a intelligence committee could decade of federal oversight. delay answering that ques- The big telecommunica- tion and issue more biparti- tions companies had lobbied san recommendations early hard to overturn the rules, contending they are heavy- next year on protecting fu- “Sith lord” Terra Larkin uses the force to celebrate the opening of “The Last Jedi” on handed and discourage invest- ture elections from foreign Thursday night at the Alamo Drafthouse Cinema in Denver. Hyoung Chang, The Denver Post tampering.