76 Mountain Guide Todd Anthony-Malone Leads Skiers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Garibaldi Provincial Park M ASTER LAN P

Garibaldi Provincial Park M ASTER LAN P Prepared by South Coast Region North Vancouver, B.C. Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Main entry under title: Garibaldi Provincial Park master plan On cover: Master plan for Garibaldi Provincial Park. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-7726-1208-0 1. Garibaldi Provincial Park (B.C.) 2. Parks – British Columbia – Planning. I. British Columbia. Ministry of Parks. South Coast Region. II Title: Master plan for Garibaldi Provincial Park. FC3815.G37G37 1990 33.78”30971131 C90-092256-7 F1089.G3G37 1990 TABLE OF CONTENTS GARIBALDI PROVINCIAL PARK Page 1.0 PLAN HIGHLIGHTS 1 2.0 INTRODUCTION 2 2.1 Plan Purpose 2 2.2 Background Summary 3 3.0 ROLE OF THE PARK 4 3.1 Regional and Provincial Context 4 3.2 Conservation Role 6 3.3 Recreation Role 6 4.0 ZONING 8 5.0 NATURAL AND CULTURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT 11 5.1 Introduction 11 5.2 Natural Resources Management: Objectives/Policies/Actions 11 5.2.1 Land Management 11 5.2.2 Vegetation Management 15 5.2.3 Water Management 15 5.2.4 Visual Resource Management 16 5.2.5 Wildlife Management 16 5.2.6 Fish Management 17 5.3 Cultural Resources 17 6.0 VISITOR SERVICES 6.1 Introduction 18 6.2 Visitor Opportunities/Facilities 19 6.2.1 Hiking/Backpacking 19 6.2.2 Angling 20 6.2.3 Mountain Biking 20 6.2.4 Winter Recreation 21 6.2.5 Recreational Services 21 6.2.6 Outdoor Education 22 TABLE OF CONTENTS VISITOR SERVICES (Continued) Page 6.2.7 Other Activities 22 6.3 Management Services 22 6.3.1 Headquarters and Service Yards 22 6.3.2 Site and Facility Design Standards -

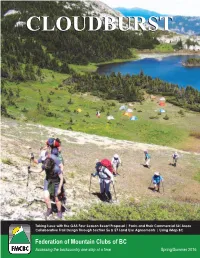

Cloudburstcloudburst

CLOUDBURSTCLOUDBURST Taking Issue with the GAS Four Season Resort Proposal | Parks and their Commercial Ski Areas Collaborative Trail Design Through Section 56 & 57 Land Use Agreements | Using iMap BC Federation of Mountain Clubs of BC Accessing the backcountry one step at a time Spring/Summer 2016 CLOUDBURST Federation of Mountain Clubs of BC Published by : Working on your behalf Federation of Mountain Clubs of BC PO Box 19673, Vancouver, BC, V5T 4E7 The Federation of Mountain Clubs of BC (FMCBC) is a democratic, grassroots organization In this Issue dedicated to protecting and maintaining access to quality non-motorized backcountry rec- reation in British Columbia’s mountains and wilderness areas. As our name indicates we are President’s Message………………….....……... 3 a federation of outdoor clubs with a membership of approximately 5000 people from 34 Recreation & Conservation.……………...…… 4 clubs across BC. Our membership is comprised of a diverse group of non-motorized back- Member Club Grant News …………...………. 11 country recreationists including hikers, rock climbers, mountaineers, trail runners, kayakers, Mountain Matters ………………………..…….. 12 mountain bikers, backcountry skiers and snowshoers. As an organization, we believe that Club Trips and Activities ………………..…….. 15 the enjoyment of these pursuits in an unspoiled environment is a vital component to the Club Ramblings………….………………..……..20 quality of life for British Columbians and by acting under the policy of “talk, understand and Some Good Reads ……………….…………... 22 persuade” we advocate for these interests. Garibaldi 2020…... ……………….…………... 27 Membership in the FMCBC is open to any club or individual who supports our vision, mission Executive President: Bob St. John and purpose as outlined below and includes benefits such as a subscription to our semi- Vice President: Dave Wharton annual newsletter Cloudburst, monthly updates through our FMCBC E-News, and access to Secretary: Mack Skinner Third-Party Liability insurance. -

Spring Ski-Ing in Wedge Pass

~ "~ Spring Ski-ing ~ "0 l:1 ~ .; ., ~ ~ in Wedge Pass ...0 .2 ., 0 :;; !::.'" '0 By W. A. Don Munday '8.. .." ...Il ., "THOSE things won't be much use here," ~ was the greeting our skis received when .. unloaded from the Paci.6c Great Eastern train '01) '0., at Alta Lake, B.C., the last week in April. ~ .... Wholly novel to local residents seemed the 0 idea of taking ski to the snow; at lake level, .Il 2,200 feet, snow lurked only in sheltered eIl" corners, for the winter's snowfall had been .tJ much less than normal. Bu t we knew the .9 driving clouds hid glacial peaks rising 5,000 to "e 7,000 feet above the lake. Although a few pairs of skis are owned around Alta Lake, the residents seem never to have discovered the real utility or joy of them. The lake is a beautiful still-unspoiled summer resort with possibilities as a winter resort. Our host was P. (Pip) H. G. Brock, the com fortable family cottage, "Primrose," being our headquarters. The third member of our party was Gilbert Hooley. The fourth, my wife, was due on the next semi-weekly train. Sproatt Mountain, rising directly for 4,800 feet from the lake, possesses a trail to a prospector's cabin near timberline, and Pip recommended this as a work-out. Scanty sun light and generous shadows marched across the morning sky. Half a mile from Primrose we passed the tragic site of the aeroplane crash which took the lives of both Pip's parents the previous summer while he was on a mountain trip with my wife and myself. -

CLOUDBURST Cover Photo Contest

CLOUDBURST Black Tusk Meadows & Tuck Lake Trail Progress Ski Skills for the Backcountry Spearhead Traverse Summer Route—Almost FEDERATION OF MOUNTAIN CLUBS OF BC Fall/Winter 2012 The Federation of Mountain Clubs of British Columbia INDEX (FMCBC) is a non-profit organization dedicated to the About the FMCBC.……………………………… 3 conservation of and the accessibility to British Colum- bia’s backcountry wilderness and mountain areas President’s Report………………………………. 4 FMCBC News……………………………………... 4 Membership in the FMCBC is open to any club or individual who supports our vision, mission and purpose. Member fees go to- Recreation & Conservation………………………. 5 wards furthering our work to protect and preserve the backcountry Trail Updates…..……………………………….. 7 for non-motorized recreation users. Member benefits include a subscription to our Cloudburst newsletter, monthly updates Club Ramblings……………...…………………. 11 through our FMCBC E-News, and access to an inexpensive third- Club Activities and Updates……………………… 15 party liability insurance program. Cover Photo Story……………………………….. 18 Backcountry Skills……………….……………… 19 FMCBC Executive Literature of Interest……………..…………..….. 20 President: Scott Webster (VOC) Treasurer: Elisa Kreller (ACC-Van) Announcements……………….…………………. 23 Secretary: Mack Skinner (NSH) Past President: Brian Wood (BCMC) FMCBC Directors Dave King (ACC-PG, CR), Caroline Clapham (ACC-Van), Andrew Cover Photo submitted by Linda Bily Pape-Salmon (VISTA), Rob Gunn and Judy Carlson (AVOC), Check out page 18 for Francis St. Pierre and Brian Wood (BCMC), -

Intermediate-Climbs-Guide-1.Pdf

Table of Conte TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface.......................................................................1 Triumph NE Ridge.....................................47 Privately Organized Intermediate Climbs ...................2 Vayu NW Ridge.........................................48 Intermediate Climbs List.............................................3 Vesper N Face..............................................49 Rock Climbs ..........................................................3 Wedge Mtn NW Rib ...................................50 Ice Climbs..............................................................4 Whitechuck SW Face.................................51 Mountaineering Climbs..........................................5 Intermediate Mountaineering Climbs........................52 Water Ice Climbs...................................................6 Brothers Brothers Traverse........................53 Intermediate Climbs Selected Season Windows........6 Dome Peak Dome Traverse.......................54 Guidelines for Low Impact Climbing...........................8 Glacier Peak Scimitar Gl..............................55 Intermediate Rock Climbs ..........................................9 Goode SW Couloir.......................................56 Argonaut NW Arete.....................................10 Kaleetan N Ridge .......................................57 Athelstan Moonraker Arete................11 Rainier Fuhrer Finger....................................58 Blackcomb Pk DOA Buttress.....................11 Rainier Gibralter Ledge.................................59 -

Legend GARIBALDI PROVINCIAL PARK

To Pemberton GARIBALDI E G D PROVINCIAL PARK I R Hwy99 I H C r T ! e A v M I B i y H s t e r y C r e e k Legend R n e e Walk-in/Wilderness r Park Boundary Camping G CALLAGHAN LAKE Vehicle/Tent Camping PROVINCIALGlacier PARK ^ Major Highway Group Camping W Mt. Moe e d g e ^ ^ Local Road, paved m o u n Mt. Cook ^ ^ Oasis Mtn No Camping t C The Owls r Mt. Weart Local Road, gravel R e t h Wedgemount r e e l Lake i Shelter C c r a l ^ e W Trail Green e ^ e G k dg t Eureka Mtn e r Lake m a Rethel Mtn. o Rainbow u e ! ! n W ^ t G W Ski Lift Day ShelterLake l r ac e Parkhurst Mtn. ie C d r C g a l l a y e g h e C a n Hiking Trail l Day-use Area Mons r e ^ e ^ Lesser Wedge Mtn e k Wedge Mtn d m a Alexander Falls o C k c b r M a c e Mountain Bikinge Traile Ranger Station B l C k r e e H k Berma Lake Cross-Country Skiing o rs Parking t Whistler! Village WHISTLER Alta ! m ! a Trail Lake ! ! n ! ! C ! ! r Alta Lake Phalanx Glacier Swimming Sani-station Wedge Hwy99 ! ! ^ Phalanx Mtn. Pass B Nita Lake ! i l l Whistler ! ! y g o ! ! Ski Area a ! ! BLACKCOMB t Wheelchair Access Toilets Gondola ! SKI AREA W BLACKCOMB GLACIER C ! r ! PROVINCIAL PARK h ! e i ! ! ^ e s ! k B Showers PointofInterest t ! Blackcomb Peak l r e ! r a . -

2019 Annual the ALPINE CLUB of CANADA

The Alpine Club of Canada • Vancouver Island Section Island Bushwhacker 2019 Annual THE ALPINE CLUB OF CANADA VANCOUVER ISLAND SECTION ISLAND BUSHWHACKER ANNUAL VOLUME 47 – 2019 Cover Image: Braiding the slopes at Hišimýawiƛ Opposite Page: Clarke Gourlay skiing at 5040 (Photo by Gary Croome) Mountain (see Page 16) (Photo by Chris Istace) VANCOUVER ISLAND SECTION OF THE ALPINE CLUB OF CANADA Section Executive 2019 Chair Catrin Brown Secretary David Lemon Treasurers Clarke Gourlay Garth Stewart National Rep Christine Fordham Education Alois Schonenberger Education Colin Mann Membership Kathy Kutzer Communication Brianna Coates Communication/Website Jes Scott Communication/Website Martin Hofmann Communication/Schedule Karun Thanjuvar Island Bushwhacker Annual Rob Macdonald Newsletter Mary Sanseverino Leadership Natasha Salway Member at Large Anya Reid Access and Environment Barb Baker Hišimýawiƛ (5040 Hut) Chris Jensen Equipment Mike Hubbard Kids and Youth Programme Derek Sou Summer Camp Liz Williams Library and Archives Tom Hall ACC VI Section Website: accvi.ca ACC National Website: alpineclubofcanada.ca ISSN 0822 - 9473 Contents REPORT FROM THE CHAIR 1 NOTES FROM THE SECTION 5 Trail Rider Program 6 Wild Women 7 Exploring the back country in partnership with the ICA Youth and Family Services program 8 Happy Anniversary: Hišimy̓ awiƛ Celebrates Its First Year 10 Clarke Gourlay 1964 - 2019 16 VANCOUVER ISLAND 17 Finding Ice on Della Falls 17 Our Surprise Wedding at the Summit of Kings Peak 21 Mount Sebalhal and Kla-anch Peaks 24 Mt Colonel Foster – Great West Couloir 26 Climbing the Island’s Arch 36 Reflection Peaks At Last 39 Climbs in the Lower Tsitika Area: Catherine Peak, Mount Kokish, Tsitika Mountain and Tsitika Mountain Southeast 42 A Return to Triple Peak 45 Rockfall on Victoria Peak 48 Mt Mariner: A Journey From Sea to Sky 51 Beginner friendly all women Traverse of the Forbidden Plateau 54 It’s not only beautiful, its interesting! The geology of the 5040 Peak area 57 Myra Creek Watershed Traverse 59 Mt. -

BLACKCOMB MASTER PLAN UPDATE 2013 Lnhistler BLACKCOMB

WHISTLER BLACKCOMB MASTER PLAN UPDATE 2013 lNHISTLER BLACKCOMB WHISTLER BLACKCOMB MASTER PLAN UPDATE 2013 BLACKCOMB Prepared for: Mr. Doug Forseth SeniorVP Operations Intrawest Cotporation 4545 Blackcomb Way Whistler, BC VON 1B4 Tel: 604 932-3141 Fax: 604 938-7527 email: dforseth@intrawestcom Prepared By: Ecosign Mountain Resort Planners Ltd. 8073 Timne P.O. Box 63 Whistler, B.C. Canada VON 1BO Tel: 604 932 5976 Fax: 604 932 1897 email: [email protected] e13 ecosign Mountain Resort Planners Ltd. FOREWORD Ecosign Mountain Resort Planners Ltd., has prepared ski area master plans in British Columbia since 1975. We prepared the first Ski Area Master Plan for Whistler Mountain in 1978 and we also prepared a conceptual Master Plan for Blackcomb Mountain in 1978 for the Blackcomb Skiing Corporation. Updates to the Master Plans for both mountains have been prepared periodically over the past 30 years. As the primary author of the Master Plans,it is important for the public, government officials and First Nations to understand that while we have worked diligently with the highly skilled and respected management team at Whistler Blackcomb, visions of the future are by their very nature imperfect. We have specifically found over the years that changes in the preferences of Whistler Blackcomb’s clientele, population demographics and new types of winter sports mean that there will need to be flexibility in the Master Plan in the future. I give just two examples: The first two master plans for each of Whistler and Blackcomb had no mention whatsoever of snowboarding and yet snowboarders now comprise about one-third of all visitors on average throughout the winter season. -

Multi-Proxy Record of Holocene Glacial History of the Spearhead and Fitzsimmons Ranges, Southern Coast Mountains, British Columbia

ARTICLE IN PRESS Quaternary Science Reviews 26 (2007) 479–493 Multi-proxy record of Holocene glacial history of the Spearhead and Fitzsimmons ranges, southern Coast Mountains, British Columbia Gerald Osborna,Ã, Brian Menounosb, Johannes Kochc, John J. Claguec, Vanessa Vallisd aDepartment of Geology and Geophysics, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alta, Canada T2N 1N4 bGeography Program, University of Northern British Columbia, Prince George, BC, CanadaV2N 4Z9 cDepartment of Earth Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada V5A 1S6 dGolder Associates Ltd., #1000, 940–6th Avenue, Calgary, Alta, Canada T2P 3T1 Received 9 February 2006; received in revised form 10 July 2006; accepted 10 September 2006 Abstract Evidence from glacier forefields and lakes is used to reconstruct Holocene glacier fluctuations in the Spearhead and Fitzsimmons ranges in southwest British Columbia. Radiocarbon ages on detrital wood and trees killed by advancing ice and changes in sediment delivery to downstream proglacial lakes indicate that glaciers expanded from minimum extents in the early Holocene to their maximum extents about two to three centuries ago during the Little Ice Age. The data indicate that glaciers advanced 8630–8020, 6950–6750, 3580–2990, and probably 4530–4090 cal yr BP, and repeatedly during the past millennium. Little Ice Age moraines dated using dendrochronology and lichenometry date to early in the 18th century and in the 1830s and 1890s. Limitations inherent in lacustrine and terrestrial-based methods of documenting Holocene glacier fluctuations are minimized by using the two records together. r 2006 Published by Elsevier Ltd. 1. Introduction is commonly interpreted to reflect enhanced sediment production beneath an expanded body of ice. -

Tb. Varsity Øtddoor Club 3Ournal

Tb. Varsity øtddoor Club 3ournal VOLUME XXXI 1988 ISSN 0524-5613 ‘7/se ?ô7ireuity of Bteah Ccs!um6.a Vscoiwi, TIlE PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Andy Pacheco The success of a club can be gauged by how many people ase inspired enough to become involved with the club activities. For an outdoor club, the major activities are, of course, trips to the mountains. Both Longhike and especially the glacier school in October attracted record numbers, and though these numbers predictably decreased as the midterms and exams came raining down, many an impromptu day trip was still thrown together at the eleventh hour in the club room Fridays. The VOC Christmas trips were all well attended, and in addition, two very successful avalanche awareness courses and a wilderness first aid course were held in December and January. Close to home, the VOC fielded many intramural teams, including two Arts 20 relay teams and frtt Storm the Wall teams. The best thing is how many people still show up at meetings and at the clubroom in Maich, even if they are too busy to go on trips. Many a summer adventure will be planned even as this article goes to the printers! Our love for the outdoors and outdoor activities does lead the VOC to get involved in various projects related to our interests. Among the prujects taken on this year: two bake sales were organized to raise funds to create the park at the Little Smoke Bluffs in Squamish. In addition, planning continues for the construction of “the Enrico Kindl memorial climbing wall” on campus, a facility which would allow for rock climbing instruction and training year round. -

Federation of Mountain Clubs of BC

Federation of Mountain Clubs of BC Accessing the backcountry one step at a time PO Box 19673 Vancouver, BC V5T 4E7 [email protected] www.mountainclubs.org Tel: 604.873.6096 March 14, 2011 By E-mail: [email protected] Chris Platz, Area Supervisor BC Parks P.O. Box 220 Brackendale, B.C. V0N 1H0 Dear Mr. Platz: Re: Renewal of Whistler Heli-ski Ltd. Park Use Permit in Garibaldi Provincial Park The Federation of Mountain Clubs of British Columbia (FMCBC) is an umbrella organization of approximately 20 outdoor recreation clubs, with about 3500 individual members in total, dispersed throughout the province. For almost four decades, the FMCBC has represented the interests of self- propelled/non-motorized backcountry recreationists by maintaining and improving backcountry and wilderness experiences for our members and the public. We understand the Whistler Heli-ski Ltd. (WHSL) park use permit in Garibaldi Provincial Park is up for renewal in 2011. The Spearhead Range has become a very popular recreation area for backcountry skiers. The growth in numbers of backcountry skiers, combined with better gear and fitness, which allow backcountry skiers to go further into the Spearhead Range on day trips, has increased the competition for skiable terrain within Garibaldi Provincial Park. This has led to greater conflicts with heli-skiers. Furthermore, as a result of the government’s inability and unwillingness to enforce designated non- motorized recreation areas within the Sea-to-Sky corridor, snowmobilers are eroding the few safe areas available for backcountry skiing and snowshoeing outside parks, and even sometimes in Garibaldi Park (Brohm Ridge – Mt. -

Th* Varsity Outdoor Qub \ Journal

Th* Varsity Outdoor Qub \ Journal i VOLUME XXIV 1981 ISSN 0524-5613 Vancouver, Canada 7Ae Umveuibj of IkitUh Columbia PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE March, 1982 Another school year has passed and so have many memorable moments in the V.O.C. This year was a good one for the V.O.C. We have seen our membership grow to a recent high of over 250. For many, the club has opened up a whole new world of adventure and challenge. For others, the club has continued to be a central part of their lives adding new memories and aspirations. The success of our club has always been in the strength of our active members. This year, again, active members gave their time unselfishly to such things as leading trips, cabin committee meetings and social functions, not to mention many others. It is these people I would like to thank most for making my job, as President, that much more enjoyable. For those of you who have participated in club activities for the first time, I urge you to take an active part in helping to run the club. I am sure you will find that the rewards far exceed the time and effort involved. As a club whose major interests lie in the outdoors, I feel we as a membership have helped people become more aware of what is beyond the campus of U.B.C. British Columbia offers a wealth of wilderness which is accessible to everyone. It is important that as a club we continue to pass on our knowledge about outdoor activities and wilderness areas.