Hieronymus De Sancta Fide and His Use of Sanhedrin Documents 249

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Author of the Gospel of John with Jesus' Mother

JOHN MARK, AUTHOR OF THE GOSPEL OF JOHN WITH JESUS’ MOTHER © A.A.M. van der Hoeven, The Netherlands, updated June 6, 2013, www.JesusKing.info 1. Introduction – the beloved disciple and evangelist, a priest called John ............................................................ 4 2. The Cenacle – in house of Mark ánd John ......................................................................................................... 5 3. The rich young ruler and the fleeing young man ............................................................................................... 8 3.1. Ruler (‘archōn’) ........................................................................................................................................ 10 Cenacle in the house of Nicodemus and John Mark .................................................................................... 10 Secret disciples ............................................................................................................................................ 12 3.2. Young man (‘neaniskos’) ......................................................................................................................... 13 Caught in fear .............................................................................................................................................. 17 4. John Mark an attendant (‘hypēretēs’) ............................................................................................................... 18 4.1. Lower officer of the temple prison .......................................................................................................... -

Mamluk Architectural Landmarks in Jerusalem

Mamluk Architectural Landmarks 2019 Mamluk Architectural in Jerusalem Under Mamluk rule, Jerusalem assumed an exalted Landmarks in Jerusalem religious status and enjoyed a moment of great cultural, theological, economic, and architectural prosperity that restored its privileged status to its former glory in the Umayyad period. The special Jerusalem in Landmarks Architectural Mamluk allure of Al-Quds al-Sharif, with its sublime noble serenity and inalienable Muslim Arab identity, has enticed Muslims in general and Sufis in particular to travel there on pilgrimage, ziyarat, as has been enjoined by the Prophet Mohammad. Dowagers, princes, and sultans, benefactors and benefactresses, endowed lavishly built madares and khanqahs as institutes of teaching Islam and Sufism. Mausoleums, ribats, zawiyas, caravansaries, sabils, public baths, and covered markets congested the neighborhoods adjacent to the Noble Sanctuary. In six walks the author escorts the reader past the splendid endowments that stand witness to Jerusalem’s glorious past. Mamluk Architectural Landmarks in Jerusalem invites readers into places of special spiritual and aesthetic significance, in which the Prophet’s mystic Night Journey plays a key role. The Mamluk massive building campaign was first and foremost an act of religious tribute to one of Islam’s most holy cities. A Mamluk architectural trove, Jerusalem emerges as one of the most beautiful cities. Digita Depa Me di a & rt l, ment Cultur Spor fo Department for e t r Digital, Culture Media & Sport Published by Old City of Jerusalem Revitalization Program (OCJRP) – Taawon Jerusalem, P.O.Box 25204 [email protected] www.taawon.org © Taawon, 2019 Prepared by Dr. Ali Qleibo Research Dr. -

John's Self-Identification to the Priests and Levites

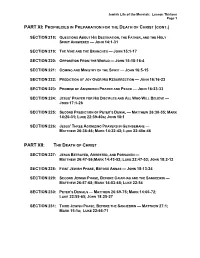

Jewish Life of the Messiah: Lesson Thirteen Page 1 PART XI: PROPHECIES IN PREPARATION FOR THE DEATH OF CHRIST (CONT.) SECTION 218: QUESTIONS ABOUT HIS DESTINATION, THE FATHER, AND THE HOLY SPIRIT ANSWERED — JOHN 14:1-31 SECTION 219: THE VINE AND THE BRANCHES — JOHN 15:1-17 SECTION 220: OPPOSITION FROM THE WORLD — JOHN 15:18-16:4 SECTION 221: COMING AND MINISTRY OF THE SPIRIT — JOHN 16:5-15 SECTION 222: PREDICTION OF JOY OVER HIS RESURRECTION — JOHN 16:16-22 SECTION 223: PROMISE OF ANSWERED PRAYER AND PEACE — JOHN 16:23-33 SECTION 224: JESUS’ PRAYER FOR HIS DISCIPLES AND ALL WHO WILL BELIEVE — JOHN 17:1-26 SECTION 225: SECOND PREDICTION OF PETER’S DENIAL — MATTHEW 26:30-35; MARK 14:26-31; LUKE 22:39-40A; JOHN 18:1 SECTION 226: JESUS’ THREE AGONIZING PRAYERS IN GETHSEMANE — MATTHEW 26:36-46; MARK 14:32-42; LUKE 22:40B-46 PART XII: THE DEATH OF CHRIST SECTION 227: JESUS BETRAYED, ARRESTED, AND FORSAKEN — MATTHEW 26:47-56;MARK 14:43-52; LUKE 22:47-53; JOHN 18:2-12 SECTION 228: FIRST JEWISH PHASE, BEFORE ANNAS — JOHN 18:13-24 SECTION 229: SECOND JEWISH PHASE, BEFORE CAIAPHAS AND THE SANHEDRIN — MATTHEW 26:57-68; MARK 14:53-65; LUKE 22:54 SECTION 230: PETER’S DENIALS — MATTHEW 26:69-75; MARK 14:66-72; LUKE 22:55-65; JOHN 18:25-27 SECTION 231: THIRD JEWISH PHASE, BEFORE THE SANHEDRIN — MATTHEW 27:1; MARK 15:1A; LUKE 22:66-71 Jewish Life of the Messiah: Lesson Thirteen Page 2 SECTION 218: QUESTIONS ABOUT HIS DESTINATION, THE FATHER, AND THE HOLY SPIRIT ANSWERED—JOHN 14:1-31 PROMISES AND ADMONITIONS BY THE KING Better known as ―The Upper Room Discourse‖ Chapters 14-17 record His table talk during the Passover Seder John, being more interested in what Jesus said rather than what He did, is the only one who records all that was said here. -

Herod's Temple of the New Testament

Dear Reader, This book was referenced in one of the 185 issues of 'The Builder' Magazine which was published between January 1915 and May 1930. To celebrate the centennial of this publication, the Pictoumasons website presents a complete set of indexed issues of the magazine. As far as the editor was able to, books which were suggested to the reader have been searched for on the internet and included in 'The Builder' library.' This is a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by one of several organizations as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. Wherever possible, the source and original scanner identification has been retained. Only blank pages have been removed and this header- page added. The original book has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books belong to the public and 'pictoumasons' makes no claim of ownership to any of the books in this library; we are merely their custodians. Often, marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in these files – a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Since you are reading this book now, you can probably also keep a copy of it on your computer, so we ask you to Keep it legal. -

Demarcation Between Sacred Space and Profane

15 Demarcationbetween SacredSpace and ProfaneSpace: The Templeof Herod Model Donald W. Parry To illustrate the pure condition of the temple of Jerusalem, the city of Jerusalem, and the land of Israel, ancient Jewish midrashim tended to exaggerate with the intent of showing the antithetical relationship between sacred and profane space. For instance, Sifre on Deuteronomy Pisqa 37 states that "the refuse of the land of Israel, is supe rior to the best place in Egypt." 1 Other accounts produced by the same author(s) relate that four kingdoms of the world argued for possession of the least significant moun tains of Israel because even the most inferior areas of the land of Israel were superior to the remaining parts of the world. 2 Why is the land of Israel superior to neighboring Egypt, and why are the least significant areas of Israel supe rior to the remaining parts of the world? The answer to this question lies in the fact that the temple of the Lord existed in the land of Israel, causing all parts of Israel to possess a degree of holiness. The fact that a temple existed in the land of Israel forced the Jewish rabbinic authorities to develop an interesting and unique theology concerning sacred space. According to several rabbinic documents, the land of Israel was divided 413 414 DONALD W. PARRY into ten concentric zones of holiness. The premier rabbinic record that identifies the various gradations of holiness is M Kelim 1:6-9. It states: There are ten degrees of holiness: The land of Israel is holier than all the [other] lands ... -

Conversion History: Ancient Period by Lawrence J

Section 1: Early history to modern times Earliest Form of "Conversion" was Assimilation The Biblical Israelites had no concept of religious conversion because the notion of a religion as separate from a nationality was incoherent. The words "Jews" and "Judaism" did not exist. Abraham was called an ivri, a Hebrew, and his descendants were known either as Hebrews, Israelites (the children of Israel), or Judeans. These words are nationalistic terms that also imply the worship of the God of Abraham. While there were no "conversions," many non-Israelites joined the Israelite community. If female, they did so by marriage or, for male and female, acceptance of the beliefs and practices of the community. In this sense, assimilation is the earliest form of conversion. Abraham and his descendants absorbed many pagans and servants into their group, greatly increasing the size of the Israelite people. We also assume the males were circumcised. Following the giving of the Torah at Sinai, the tribes were circumcised. The assumption was that the children of the non-Israelites who joined the nation as it left Egypt also were circumcised and accepted into the nation. Next they increased their numbers from among non-Israelite peoples as they conquered the land as quoted from Deuteronomy 21:10-14: “When you go out to war against your enemies, and the LORD your God gives them into your hand and you take them captive, and you see among the captives a beautiful woman, and you desire to take her to be your wife, and you bring her home to your house, she shall shave her head and pare her nails. -

Before the Council Acts 22:30-23:11 Thought for the Week

w e e k o n e before the Council Acts 22:30-23:11 thought for the week During the second Temple period the Great Sanhedrin was the primary legal assembly of the Jewish faith, it met in the Hall of Hewn Stones in the Temple in Jerusalem. The council is understood to have had both political and religious authority during Roman occupation. It had, according to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, the power to, “appoint the king and the high priest, declare war, and expand the territory of Jerusalem and the Temple. Judicially, it could try a high priest, a false prophet, a rebellious elder, or an errant tribe. Religiously, it supervised certain rituals, including the Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement) liturgy.” At this time, it is thought that the council was constituted of both Priests and leading Jewish families, or as the Gospels say, “chief priests, elders, and scribes” (Luke 22:66). That Paul was brought before the Sanhedrin, as Jesus had been, is an indication of how seriously the effect he was having on the people was taken! Paul’s voice, just like that of Jesus was being heard by both the Roman and the Jewish authorities and they did not like it! verse for the week prayer for the week The following night the Lord stood Lord may all of who I am speak of near Paul and said, “Take courage! As you, you have testified about me in May my words speak of hope, Jerusalem, so you must also testify in May my actions speak of love, Rome.” May my relationships speak of Acts 23 verse 11 grace, May my prayers speak of mercy, image for the week May my living shout the name of Jesus, And my breathing make you known. -

Herod's Temple : Its New Testament Associations and Its Actual

|RODS TEMPLE I NEW TESTAMENT isOCIATIONS AND 1 ACTUAL STRUCTURE IV. SHAW" ( » j i »; i ui iii ^ wltr? CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Cornell University Library DS 109.3.C14H5 Herod's Temple : 3 1924 028 590 374 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924028590374 HEROD'S TEMPLE —— — — — — . BY THE SAME AUTHOR THE TABERNACLE : Its History and Structure. With Preface by Prof. Sayce, D.D. Second Edition. 5S. Religious Tract Society, London. " Exhausts the subject." Scotsman. " Interesting, unconventional and original." Record. " A monument of research." Birmingham Post. " Deeply interesting : a new departure." The Chi-istian. SOLOMON'S TEMPLE: Its History and Structure. With Preface by Prof. Sayce, D.D. Second Edition. 6S. Religious Tract Society, London. THE SECOND TEMPLE IN JERUSALEM: Its History and its Structure. Illustrated with two large Folding Plans, each measuring 2ojns. by 15 ins., and six other Maps and Plans. Demy 8vo. 412 pp. Published at 10s. 6d. New Copies 5s. The Times Book Club, 376, Oxford Street, London, W. " He presents a mass of information which cannot fail to be of service to every student of the Bible." Expository Times, " _ Painstaking, illustrative, and suggestive as its predecessors. It is instruc- tive that an architect has been able to reproduce Ezekiel's design solely from the schedule of the ninety-six architectural measurements given by Ezekiel, which Mr. Caldecott has drawn up in his first appendix." British Weekly. LEAVES OF A LIFE. -

Antiquities in the Basement: Ideology and Real Estate at the Expense of Archaeology in Jerusalem’S Old City

Antiquities in the Basement: Ideology and Real Estate at the Expense of Archaeology In Jerusalem’s Old City 2015 October 2015 Table of contents >> Introduction 3 This booklet has been written by Emek Shaveh staff. >> General Background 3 Edited by: Dalia Tessler Translation: Samuel Thrope, Jessica Bonn >> Chapter 1. Graphic design: Lior Cohen The Strauss Building - Antiquities in the Toilet 5 Proof editing: Talya Ezrahi >> Chapter 2. Photographs: Emek Shaveh Tourism and Sacred Sites: The Davidson Center, the Archaeological Park, and the Corner of the Western Wall 8 >> Chapter 3. “Ohel Yitzchak”: A Jewish Museum in a Mamluk Bathhouse 10 >> Chapter 4. Emek Shaveh (cc) | Email: [email protected] | website www.alt-arch.org Beit HaLiba – First Approve and Only Then Take Stock Of the Destruction 15 Emek Shaveh is an organization of archaeologists and heritage professionals focusing on the >> Chapter 5. role of tangible cultural heritage in Israeli society and in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. We "In a piecemeal manner": The Comprehensive Plan for the Western Wall Plaza 19 view archaeology as a resource for strengthening understanding between different peoples and cultures. This publication was produced by Emek Shaveh (A public benefit corporation) with the support of the Norwegian Embassy in Israel, the Federal Department for Foreign Affairs Switzerland (FDFA), Irish Foreign Ministry, CCFD and Cordaid. Responsibility for the information contained in this report belongs exclusively to Emek Shaveh. This information does not represent the opinions of the abovementioned donors. Introduction The present volume is a series of abstracts based on longer reports by Emek Shaveh as in the IAA excavations at the Givati Parking Lot (A Privatized Heritage, November 2014), which draw on internal documents of the Israel Antiquities Authority (henceforth: IAA),1 shows that this is a routine modus operandi rather than exceptions to the rule.2 obtained under the Freedom of Information Law. -

The Temple: Its Ministry and Services

iMiii THE TEMPLE PLAN OF THE TEMPLE AT THE TIME OF OUR LORD. 4 THE TEMPLE ITS MINISTRY AND SERVICES As they were at the time of Jesus Christ BY THE REV. DR. EDERSHEIM / I AUTHOR OF " SKETCHES OF JEWISH SOCIAL LIFE," ETC. LONDON RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY 4, Bouverie St., and 65, Sl Paul's Churchyard, E.C. E4 MADE IN GREAT BRITAIN. JPJMNTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LTD. I.ONDON AND BECCLES. PREFACE It has been my wish in this book, to take the reader it back nineteen centuries ; to show him Jerusalem as was, when our Lord passed through its streets, and the Sanctuary, when He taught in its porches and courts ; to portray, not only the appearance and structure of the Temple, but to describe its ordi- nances and worshippers, the ministry of its priest- hood, and the ritual of its services. In so doing, I have hoped, not only to illustrate a subject, in itself most interesting to the Bible-student, but also, and chiefly, to sketch, in one important aspect, the religious life of the period in which our blessed Lord lived upon earth, the circumstances under which He taught, and the religious rites by which He was surrounded ; and whose meaning, in their truest sense, He came to fulfil. The Temple and its services form, so to speak, part life of the and work of Jesus Christ ; part also of His teaching, and of that of His apostles. What connects itself so closely with Him must be of deepest interest We want to be able, as it were, to enter Jerusalem in His train, along with those who on that Palm-Sunday 744068 ( PREFACE ' * cried, Hosanna to the Son of David ; to see its streets and buildings ; to know exactly how the Temple looked, and to find our way through its gates, among its porches, courts, and chambers ; to be present in spirit at its services ; to witness the Morning and the Evening Sacrifice ; to mingle with the crowd of worshippers at the great Festivals, and to stand by the side of those who offered sacrifice or free-will offering, or who awaited the solemn purification which would restore them to the fellowship of the Sanctuary. -

The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah Alfred Edersheim 1883

The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah Alfred Edersheim 1883 Book III THE ASCENT: FROM THE RIVER JORDAN TO THE MOUNT OF TRANSFIGURATION 'In every passage of Scripture where thou findest the Majesty of God, thou also findest close by His Condescension (Humility). So it is written down in the Law [Deut. x. 17, followed by verse 18], repeated in the Prophets [Is. lvii. 15], and reiterated in the Hagiographa [Ps. lxviii. 4, followed by verse 5].' - Megill 31 a. Chapter 1 THE TEMPTATION OF JESUS (St. Matthew 4:1-11; St. Mark 1:12,13; St. Luke 4:1-13.) The proclamation and inauguration of the 'Kingdom of Heaven' at such a time, and under such circumstances, was one of the great antitheses of history. With reverence be it said, it is only God Who would thus begin His Kingdom. A similar, even greater antithesis, was the commencement of the Ministry of Christ. From the Jordan to the wilderness with its wild Beasts; from the devout acknowledgment of the Baptist, the consecration and filial prayer of Jesus, the descent of the Holy Spirit, and the heard testimony of Heaven, to the utter foresakeness, the felt want and weakness of Jesus, and the assaults of the Devil - no contrast more startling could be conceived. And yet, as we think of it, what followed upon the Baptism, and that it so followed, was necessary, as regarded the Person of Jesus, His Work, and that which was to result from it. Psychologically, and as regarded the Work of Jesus, even reverent negative Critics1 have perceived its higher need. -

The Temple--Its Ministry and Services

The Temple--Its Ministry and Services Author(s): Edersheim, Alfred (1825-1889) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: Alfred Edersheim has done much work to provide a context in which readers can understand the Old and New Testa- ments. This work is no exception. Temple--Its Ministry and Services provides a historical examination of the first century Temple at Jerusalem. Edersheim provides beautiful and lush descriptions of the Temple. These descriptions help convey a sense of holiness and reverence that the Temple must have commanded. In the Preface, Edersheim notes that not everyone will find all the details of Temple interesting. Fortu- nately, the bulk of the text is arranged in short sections, each containing a paragraph or two. For topics readers are unin- terested in, they can easily skip to the next short section. This feature also makes the work a useful reference tool. Throughout Temple, Edersheim takes his points and relates them to New Testament events and themes. Although the writing is somewhat dated, Temple--Its Ministry and Services provides a fascinating and enriching look at the Temple. Tim Perrine CCEL Staff Writer Subjects: Judaism Practical Judaism i Contents Title Page 1 Preface 2 A First View of Jerusalem, and of the Temple 6 Within the Holy Place 16 Temple Order, Revenues, and Music 27 The Officiating Priesthood 39 Sacrifices: Their Order and Their Meaning 52 The Burnt-Offering, the Sin- and Trespass-Offering, and the Peace-Offering 63 At Night in the Temple 73 The Morning