Synoptic Gospels, by Dr. Robert C. Newman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Author of the Gospel of John with Jesus' Mother

JOHN MARK, AUTHOR OF THE GOSPEL OF JOHN WITH JESUS’ MOTHER © A.A.M. van der Hoeven, The Netherlands, updated June 6, 2013, www.JesusKing.info 1. Introduction – the beloved disciple and evangelist, a priest called John ............................................................ 4 2. The Cenacle – in house of Mark ánd John ......................................................................................................... 5 3. The rich young ruler and the fleeing young man ............................................................................................... 8 3.1. Ruler (‘archōn’) ........................................................................................................................................ 10 Cenacle in the house of Nicodemus and John Mark .................................................................................... 10 Secret disciples ............................................................................................................................................ 12 3.2. Young man (‘neaniskos’) ......................................................................................................................... 13 Caught in fear .............................................................................................................................................. 17 4. John Mark an attendant (‘hypēretēs’) ............................................................................................................... 18 4.1. Lower officer of the temple prison .......................................................................................................... -

The Synoptic Gospels, Revised and Expanded an Introduction 2Nd Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE SYNOPTIC GOSPELS, REVISED AND EXPANDED AN INTRODUCTION 2ND EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Keith F Nickle | 9780664223496 | | | | | The Synoptic Gospels, Revised and Expanded An Introduction 2nd edition PDF Book See details for additional description. About this product. Jesus Under Fire. In a clear and concise manner, Nickles explores the major issues of faith that influenced the writers of the Gospels. Ask a Question What would you like to know about this product? The Story of Romans. Be the first to write a review About this product. Privacy Policy Terms of Use. Write a Review. Bible Sale of the Season. Sign in or create an account. Enter email address. Jesus and the First Three Gospels. By: Robert H. The Synoptic Gospels. You can unsubscribe at any time. An Introduction to The Gospels. Jesus, Justice and the Reign of God. Be the first to write a review. Wishlist Wishlist. Toggle navigation. Judaism When Christianity Began. Studying the Synoptic Gospels, Second Edition. Keith Nickle provides a revised and updated edition of a well-respected resource that fills the gap between cursory treatments of the Synoptic Gospels by New Testament introductions and exhaustive treatments in commentaries. We believe this work is culturally important, and. The Targum Onquelos to the Torah: Genesis. Barry Rubin. Will be clean, not soiled or stained. Literary Forms in the New Testament. The Synoptic Gospels, Revised and Expanded An Introduction 2nd edition Writer Paperback Books Revised Edition. The Synoptic Gospels is helpful for classroom or personal use. Sign in or create an account. Best Selling in Nonfiction See all. No ratings or reviews yet No ratings or reviews yet. -

MEMORY, JESUS, and the SYNOPTIC GOSPELS Resources for Biblical Study

MEMORY, JESUS, AND THE SYNOPTIC GOSPELS Resources for Biblical Study Tom Th atcher, New Testament Editor Number 59 MEMORY, JESUS, AND THE SYNOPTIC GOSPELS MEMORY, JESUS, AND THE SYNOPTIC GOSPELS By Robert K. McIver Society of Biblical Literature Atlanta MEMORY, JESUS, AND THE SYNOPTIC GOSPELS Copyright © 2011 by the Society of Biblical Literature All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Offi ce, Society of Biblical Literature, 825 Houston Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data McIver, Robert K. (Robert Kerry), 1953– Memory, Jesus, and the Synoptic Gospels / by Robert K. McIver. p. cm. — (Society of Biblical Literature resources for biblical study ; no. 59) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and indexes. ISBN 978-1-58983-560-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-1-58983-561-0 (electronic format) 1. Bible. N.T. Gospels—Criticism, interpretation, etc. 2. Memory—Religious aspects— Christianity. 3. Jesus Christ—Historicity. I. Title. BS2555.52.M35 2011 232.9'08—dc22 2011014983 Printed on acid-free, recycled paper conforming to ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) and ISO 9706:1994 standards for paper permanence. Contents List of Tables -

Learning Experience What Are the Synoptic Gospels? (25 Minutes)

Learning Experience What Are the Synoptic Gospels? (25 minutes) Activity Plan 1. You will want to have read the Catechist Background information prior to beginning this part of the lesson. 2. Introduce the learning experience with these, or similar, words: Have you ever noticed that some passages, sayings of Jesus, even stories in one gospel are nearly identical to that found in one or more of the other gospels? Let me show you what I mean. Would someone please read aloud Matthew 3:13-17? . Now, would someone please read aloud Mark 1:9-11? . And lastly, would someone please read aloud Luke 3:21-22? It’s uncanny how similar are these passages. You would think the authors were copying from the same source! And if that is what you are thinking then, YOU ARE RIGHT! The Synoptic Gospels are the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. They are called synoptic (which means “seen together”) (like synonym) because they can be compared column by column with each other. The three Synoptic Gospels have many parables and accounts in common, as well as a general consensus on the order of events, suggesting a common source for all three. As we will see, the writers of these gospels were indeed using some of the same sources. You may be asking why each Gospel writer would retell story based on the same source of information. Studying each of the Synoptic writers in more detail will reveal that each wrote to a different audience and for different reasons. For example, the writer of the Gospel of Luke (who may have been a physician) wrote to, and on behalf of the widow, the poor, orphaned and marginalized. -

Mamluk Architectural Landmarks in Jerusalem

Mamluk Architectural Landmarks 2019 Mamluk Architectural in Jerusalem Under Mamluk rule, Jerusalem assumed an exalted Landmarks in Jerusalem religious status and enjoyed a moment of great cultural, theological, economic, and architectural prosperity that restored its privileged status to its former glory in the Umayyad period. The special Jerusalem in Landmarks Architectural Mamluk allure of Al-Quds al-Sharif, with its sublime noble serenity and inalienable Muslim Arab identity, has enticed Muslims in general and Sufis in particular to travel there on pilgrimage, ziyarat, as has been enjoined by the Prophet Mohammad. Dowagers, princes, and sultans, benefactors and benefactresses, endowed lavishly built madares and khanqahs as institutes of teaching Islam and Sufism. Mausoleums, ribats, zawiyas, caravansaries, sabils, public baths, and covered markets congested the neighborhoods adjacent to the Noble Sanctuary. In six walks the author escorts the reader past the splendid endowments that stand witness to Jerusalem’s glorious past. Mamluk Architectural Landmarks in Jerusalem invites readers into places of special spiritual and aesthetic significance, in which the Prophet’s mystic Night Journey plays a key role. The Mamluk massive building campaign was first and foremost an act of religious tribute to one of Islam’s most holy cities. A Mamluk architectural trove, Jerusalem emerges as one of the most beautiful cities. Digita Depa Me di a & rt l, ment Cultur Spor fo Department for e t r Digital, Culture Media & Sport Published by Old City of Jerusalem Revitalization Program (OCJRP) – Taawon Jerusalem, P.O.Box 25204 [email protected] www.taawon.org © Taawon, 2019 Prepared by Dr. Ali Qleibo Research Dr. -

John's Self-Identification to the Priests and Levites

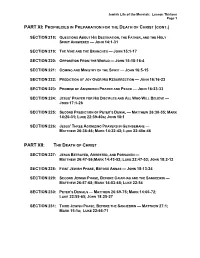

Jewish Life of the Messiah: Lesson Thirteen Page 1 PART XI: PROPHECIES IN PREPARATION FOR THE DEATH OF CHRIST (CONT.) SECTION 218: QUESTIONS ABOUT HIS DESTINATION, THE FATHER, AND THE HOLY SPIRIT ANSWERED — JOHN 14:1-31 SECTION 219: THE VINE AND THE BRANCHES — JOHN 15:1-17 SECTION 220: OPPOSITION FROM THE WORLD — JOHN 15:18-16:4 SECTION 221: COMING AND MINISTRY OF THE SPIRIT — JOHN 16:5-15 SECTION 222: PREDICTION OF JOY OVER HIS RESURRECTION — JOHN 16:16-22 SECTION 223: PROMISE OF ANSWERED PRAYER AND PEACE — JOHN 16:23-33 SECTION 224: JESUS’ PRAYER FOR HIS DISCIPLES AND ALL WHO WILL BELIEVE — JOHN 17:1-26 SECTION 225: SECOND PREDICTION OF PETER’S DENIAL — MATTHEW 26:30-35; MARK 14:26-31; LUKE 22:39-40A; JOHN 18:1 SECTION 226: JESUS’ THREE AGONIZING PRAYERS IN GETHSEMANE — MATTHEW 26:36-46; MARK 14:32-42; LUKE 22:40B-46 PART XII: THE DEATH OF CHRIST SECTION 227: JESUS BETRAYED, ARRESTED, AND FORSAKEN — MATTHEW 26:47-56;MARK 14:43-52; LUKE 22:47-53; JOHN 18:2-12 SECTION 228: FIRST JEWISH PHASE, BEFORE ANNAS — JOHN 18:13-24 SECTION 229: SECOND JEWISH PHASE, BEFORE CAIAPHAS AND THE SANHEDRIN — MATTHEW 26:57-68; MARK 14:53-65; LUKE 22:54 SECTION 230: PETER’S DENIALS — MATTHEW 26:69-75; MARK 14:66-72; LUKE 22:55-65; JOHN 18:25-27 SECTION 231: THIRD JEWISH PHASE, BEFORE THE SANHEDRIN — MATTHEW 27:1; MARK 15:1A; LUKE 22:66-71 Jewish Life of the Messiah: Lesson Thirteen Page 2 SECTION 218: QUESTIONS ABOUT HIS DESTINATION, THE FATHER, AND THE HOLY SPIRIT ANSWERED—JOHN 14:1-31 PROMISES AND ADMONITIONS BY THE KING Better known as ―The Upper Room Discourse‖ Chapters 14-17 record His table talk during the Passover Seder John, being more interested in what Jesus said rather than what He did, is the only one who records all that was said here. -

Christ in the Synoptic Gospels

Christ in the Synoptic Gospels REGULAR BAPTIST PRESS 1300 North Meacham Road Schaumburg, Illinois 60173-4806 Executive Director: David M. Gower Director of Educational Resources: Valerie A. Wilson Assistant Editors: Jonita Barram; Melissa Meyer Art Director: Steve Kerr Cover Design: Jim Johnson Production: Deb Wright ONE SOLITARY LIFE: CHRIST IN THE SYNOPTIC GOSPELS Adult Bible Study Leader’s Guide Vol. 53 • No. 1 © 2004 • Regular Baptist Press 1-800-727-4440 • www.regularbaptistpress.org RBP1626 • ISBN: 1-59402-143-0 Contents How to Use Life Design . 5 Preface . 6 Introduction . 7 Comparative Chart of the Gospels . 10 LESSON 1 Begotten Alone: Incarnation . 11 LESSON 2 He Fought Alone: Temptation . 19 LESSON 3 He Cared Alone: Compassion . 26 LESSON 4 He Sought Them Alone: Evangelization. 31 LESSON 5 He Taught Alone: Education . 37 LESSON 6 He Was Glorified Alone: Transfiguration . 42 LESSON 7 He Was Rejected Alone: Opposition . 48 LESSON 8 He Offered Alone: Presentation . 54 LESSON 9 He Prayed Alone: Intercession . 61 LESSON 10 He Stood Alone: Accusation. 67 LESSON 11 He Died Alone: Crucifixion . 74 LESSON 12 He Arose Alone: Resurrection . 80 LESSON 13 One Solitary Life: A Review . 88 Answers to Bible Study Questions . 95 How to Use Life Design LIFE DESIGN: Bible rial in the Bible study than you can cover in one class Study Designed for the session. Ask God to help you as you tailor the lesson Life You Live. These for your learners. Bible study materials are The Study Book designed to engage adult This leader’s guide is designed to accompany the learners in inductive Bible study book. -

The Synoptic Gospels by Felix Just, S.J., Ph.D

The Synoptic Gospels by Felix Just, S.J., Ph.D. The "Synoptic Gospels"- The Gospels according to Matthew, Mark, and Luke are so similar to each other that, in a sense, they view Jesus "with the same eye" (syn-optic), in contrast to the very different picture of Jesus presented in the Fourth Gospel (John). Yet there are also many significant differences among the three Synoptic Gospels. The "Synoptic Problem" - The similarities between Matthew, Mark, and Luke are so numerous and so close, not just in the order of the material presented but also in the exact wording of long stretches of text, that it is not sufficient to explain these similarities on the basis of common oral tradition alone. Rather, some type of literary dependence must be assumed as well. That is, someone copied from someone else's previously written text; several of the evangelists must have used one or more of the earlier Gospels as sources for their own compositions. The situation is complicated because some of the material is common to all three Synoptics, while other material is found in only two out of these three Gospels.. Moreover, the common material is not always presented in the same order in the various Gospels. So, the question remains, who wrote first, and who copied from whom? The Four-Source Theory (the solution accepted by most scholars today) Mark = the oldest written Gospel, which provided the narrative framework for both Matt and Luke Q = "Quelle" = a hypothetical written "Source" of some sayings / teachings of Jesus (now lost?). By definition Q consists of materials found in Matthew and Luke and not in Mark M = various other materials (mostly oral, some maybe written) found only in Matthew L = various other materials (mostly oral, others probably written) found only in Luke Note: the arrows indicate direction of influence; older materials are above, later Gospels below Markan Priority - For most of Christian history, people thought that Matthew was the first and oldest Gospel, and that Mark was a later, shorter version of the same basic message. -

Concordia Theological Quarterly

Concordia Theological Quarterly Volume 79:3–4 July/October 2015 Table of Contents The Lutheran Hymnal after Seventy-Five Years: Its Role in the Shaping of Lutheran Service Book Paul J. Grime ..................................................................................... 195 Ascending to God: The Cosmology of Worship in the Old Testament Jeffrey H. Pulse ................................................................................. 221 Matthew as the Foundation for the New Testament Canon David P. Scaer ................................................................................... 233 Luke’s Canonical Criterion Arthur A. Just Jr. ............................................................................... 245 The Role of the Book of Acts in the Recognition of the New Testament Canon Peter J. Scaer ...................................................................................... 261 The Relevance of the Homologoumena and Antilegomena Distinction for the New Testament Canon Today: Revelation as a Test Case Charles A. Gieschen ......................................................................... 279 Taking War Captive: A Recommendation of Daniel Bell’s Just War as Christian Discipleship Joel P. Meyer ...................................................................................... 301 Marriage, Divorce, and Remarriage: The Triumph of Culture? Gifford A. Grobien ............................................................................ 315 Pastoral Care and Sex Harold L. Senkbeil ............................................................................. -

Herod's Temple of the New Testament

Dear Reader, This book was referenced in one of the 185 issues of 'The Builder' Magazine which was published between January 1915 and May 1930. To celebrate the centennial of this publication, the Pictoumasons website presents a complete set of indexed issues of the magazine. As far as the editor was able to, books which were suggested to the reader have been searched for on the internet and included in 'The Builder' library.' This is a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by one of several organizations as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. Wherever possible, the source and original scanner identification has been retained. Only blank pages have been removed and this header- page added. The original book has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books belong to the public and 'pictoumasons' makes no claim of ownership to any of the books in this library; we are merely their custodians. Often, marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in these files – a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Since you are reading this book now, you can probably also keep a copy of it on your computer, so we ask you to Keep it legal. -

Gospel of Matthew 101

GOSPEL OF MATTHEW 101 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Most books of the Bible don’t come with standard bylines, and the Gospel of Matthew is no exception. While early Christian tradition attributes authorship of this gospel to Matthew, one of Jesus’ disciples, many modern scholars dispute the notion. Instead, scholars contend the author of Matthew was likely a Jewish man writing around 80 CE who drew upon the Gospel of Mark (including 600 of Mark’s 661 verses) but also expanded the narrative. Even if the Apostle Matthew is not the writer of the gospel, his story gives us insight into the life and ministry of Jesus. Matthew, also known as Levi, is a tax collector, a role viewed with disdain. By selecting Matthew as a disciple, Jesus shows again by example that all people are beloved children of God, that all are worthy of love, forgiveness, and redemption. While Matthew appears in all four gospels and in the Book of Acts, we know very little about the rest of his life or how he died, only that he was a faithful companion and disciple of Jesus. ABOUT THE GOSPEL OF MATTHEW The Gospel of Matthew is one of the three synoptic gospels, along with Mark and Luke. These three gospels share many of the same stories and sometimes the same words. Despite some similarities, Matthew expands on key teachings of Jesus and features a number of parables and stories not found in the other gospels. For instance, it’s only in Matthew that we hear about the Magi making their trek across the desert with gifts for baby Jesus. -

Volume 79:3–4 July/October 2015

Concordia Theological Quarterly Volume 79:3–4 July/October 2015 Table of Contents The Lutheran Hymnal after Seventy-Five Years: Its Role in the Shaping of Lutheran Service Book Paul J. Grime ..................................................................................... 195 Ascending to God: The Cosmology of Worship in the Old Testament Jeffrey H. Pulse ................................................................................. 221 Matthew as the Foundation for the New Testament Canon David P. Scaer ................................................................................... 233 Luke’s Canonical Criterion Arthur A. Just Jr. ............................................................................... 245 The Role of the Book of Acts in the Recognition of the New Testament Canon Peter J. Scaer ...................................................................................... 261 The Relevance of the Homologoumena and Antilegomena Distinction for the New Testament Canon Today: Revelation as a Test Case Charles A. Gieschen ......................................................................... 279 Taking War Captive: A Recommendation of Daniel Bell’s Just War as Christian Discipleship Joel P. Meyer ...................................................................................... 301 Marriage, Divorce, and Remarriage: The Triumph of Culture? Gifford A. Grobien ............................................................................ 315 Pastoral Care and Sex Harold L. Senkbeil .............................................................................