Jenkins Family Interview, 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hicks, Robert "Bob", House Other Names/Site Number: N/A Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A

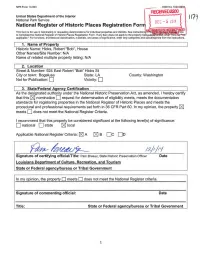

NPS Form 10-900 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service DEC - 5 i:014 National Register of Historic Places Registration For s This fom, is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instruction ~ w to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property be o.g..d! r-"rrOt' applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories- from the instructions. Historic Name: Hicks, Robert "Bob", House Other Names/Site Number: N/A Name of related multiple property listing: N/A [ 2. Location Street & Number: 924 East Robert "Bob" Hicks St City or town: Bogalusa State: LA County: Washington Not for Publication: D Vicinity: D 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this ~ nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets, meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property~ meets D does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: D national D state ~ local Applicable National Register Criteria: ~ A ~B De Do Signature of certifying official/Title: Pam Breaux, State Historic Preservation Officer Date Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation, and Tourism State or Federal a enc /bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property D meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Robert "Bob" Hicks House, Washington Parish, LA Robert "Bob" Hicks House, Washington Parish, LA

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 Hicks, Robert “Bob” , House Washington Parish, LA Name of Property County and State 4. National Park Certification I hereby certify that the property is: ___ entered in the National Register ___ determined eligible for the National Register ___ determined not eligible for the National Register ___ removed from the National Register ___other, explain: ___________________________ Signature of the Keeper Date of Action 5. Classification Ownership of Property (Check as many boxes as apply.) x Private Public – Local Public – State Public – Federal Category of Property (Check only one box.) x Building(s) District Site Structure object Number of Resources within Property (Do not include previously listed resources in the count) Contributing Non -contributing 2 Buildings Sites Structures Objects 2 0 Total Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National Register: 0 6. Function or Use Historic Functions (Enter categories from instructions.): Domestic: Single Dwelling Current Functions (Enter categories from instructions.): Vacant/Not in Use 2 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 Hicks, Robert “Bob” , House Washington Parish, LA Name of Property County and State 7. Description Architectural Classification (Enter categories from instructions.): No Style Materials: (enter categories from instructions.) foundation: Concrete blocks walls: Wood Siding roof: Asphalt Shingles other: Narrative Description (Describe the historic and current physical appearance and condition of the property. Describe contributing and noncontributing resources if applicable. -

A Historical Analysis of Black Women and Armed Resistance, 1959-1979

STRAPPED: A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF BLACK WOMEN AND ARMED RESISTANCE, 1959-1979 By: JASMIN A. YOUNG A Dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History written under the direction of Deborah Gray White and approved by _________________________ _________________________ _________________________ _________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey MAY, 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Strapped: A Historical Analysis of Black Women and Armed Resistance, 1959-1979 by JASMIN A. YOUNG Dissertation Director: Deborah Gray White “Strapped: A Historical Analysis of Black Women and Armed Resistance, 1959-1979” is an intellectual and cultural study that broadens our understanding of the Black freedom movement by analyzing Black women who engaged in armed resistance from 1959 to 1979. I argue Black women increasingly embraced the tactic of armed resistance as a tool to achieve full freedom in post-World War II America. This work is significant because it offers a departure from previous scholars who have overwhelmingly assumed that armed resistance was the primary domain of Black men including Tim Tyson and Lance Hill. My doctoral project offers a different interpretation by separating armed self-defense from masculinity. I draw from and build on the histories of Black women, gender theories, and social movement scholarship to show that armed resistance was prevalent among Black women. Using a vast array of primary source materials such as newspapers, interviews, organizational documents, and government surveillance records, I analyze how the government's response to citizens’ demands for civil and human rights shaped the tactics Black women employed, including armed resistance. -

Interview - 5-27-11 Page 1 of 67

Hicks Family Interview - 5-27-11 Page 1 of 67 Civil Rights History Project Interview completed by the Southern Oral History Program under contract to the Smithsonian Institution ’s National Museum of African American History & Culture and the Library of Congress, 2011 Interviewees: Seven members of the family of Mr. Robert Lawrence Hicks Sr. (deceased): grandson Darryl Hicks (son of Robert L. Hicks Jr.); son Gregory Hicks; daughter Carol Cummings Burras; son Robert Lawrence Hicks Jr.; son Charles Ray Hicks (nickname ‘Chuck’); surviving spouse Mrs. Valeria (Payton) Hicks (nicknames ‘Jackie’ or ‘Jack’); daughter Barbara Maria Hicks Collins Interview Date: May 27, 2011 Location: Hicks family home, Bogalusa, Louisiana Interviewer: Joseph Mosnier, Ph.D. Videographer: John Bishop Interview length: Special notes: Also present as observers during the interview: Ms. Elaine Nichols of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture; longtime Hicks family friend Dr. Rickey Hill, a Bogalusa native who is now a dean at Mississippi Valley State University Note: The seven participating Hicks family members sat left-to-right as follows: grandson Darryl Hicks (son of Robert L. Hicks Jr.); son Gregory Hicks; daughter Carol Cummings Burras; son Robert Lawrence Hicks Jr.; son Charles Ray Hicks (nicknamed ‘Chuck’); surviving spouse Mrs. Valeria Hicks (nicknamed ‘Jackie ’ or ‘Jack); daughter Barbara Maria Hicks Collins. [Periodically, throughout the interview, background sounds like those made by a passing vehicle with a loud muffler are heard - specific occurrences are not noted in the text] [Conversation, laughter, and picture taking before interview begins] John Bishop: Can I start with you and your name? Darryl Hicks: Darryl. -

Lance-Hill-The-Deacons-For-Defense

The Deacons for Defense The Deacons armed resistance and the civil rights movement Lance Hill for Defense The University of North Carolina Press Chapel Hill and London ∫ 2004 The University of North Carolina Press All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Designed by Jacquline Johnson Set in Charter by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hill, Lance E. (Lance Edward), 1950– The Deacons for Defense : armed resistance and the civil rights movement / Lance Hill. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-8078-2847-5 (alk. paper) 1. Deacons for Defense and Justice—History. 2. African American civil rights workers— Louisiana—Jonesboro—History—20th century. 3. Self-defense—Political aspects—Southern States—History—20th century. 4. Political violence—Southern States—History—20th century. 5. Ku Klux Klan (1915– )—History—20th century. 6. African Americans—Civil rights—Southern States—History—20th century. 7. Civil rights movements—Southern States—History—20th century. 8. Southern States—Race relations. 9. Louisiana—Race relations. 10. Mississippi—Race relations. I. Title. e185.615.h47 2004 323.1196%073%009046—dc22 2003021779 080706050454321 For Eileen Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1 Beginnings 10 2 The Deacons Are Born 30 3 In the New York Times 52 4 Not Selma 63 5 On to Bogalusa 78 6 The Bogalusa Chapter 96 7 The Spring Campaign 108 8 With a Single Bullet 129 9 Victory 150 10 Expanding in the Bayou State 165 11 Mississippi Chapters 184 12 Heading North 216 13 Black Power—Last Days 234 Conclusion: The Myth of Nonviolence 258 Notes 275 Bibliography 335 Index 353 A section of photographs appears after p. -

Disrespecting the President DOC Metairie Re-Opens

Lighting The Road To The Future Data Zone Page 6 The Amen Corner “The People’s Paper” February 4 - February 10, 2012 46th Year Volume 36 www.ladatanews.com Page 2 Newsmaker Opinion DOC Metairie Disrespecting Re-Opens the President Page 5 Page 4 Page 2 February 4 - February 10, 2012 Cover Story www.ladatanews.com New Orleans Continuing a Rich History Norman “Jelly Roll” Morton Mahalia Jackson been an important part of the allure and magic that would like to pay tribute to a few of the many Black Written and Edited by Edwin Buggage makes the City come alive? The world has come to New Orleanians who have contributed, leaving know the City for its food and music, but in other their marks on the world . But this is only an entry New Orleans: A City areas New Orleans is just as important . Many who point into encouraging you to explore the history and its History have set precedents and been on the frontlines of and contributions of African-Americans to New Or- the struggle for Civil Rights, to inventors and in- leans . New Orleans is a City with a rich cultural heri- novators in so many fields of endeavor have called tage . It is a unique place with a mix of people com- New Orleans home . Today nearly three centuries ing together throughout its history producing a after its founding it continues to be the gateway to Jelly Roll Morton: gumbo of a place . One of the main ingredients that the world as a truly fascinating place that has the Jazz Pioneer have given it its flavor that keeps people savoring distinction as being the most international and Af- the taste of the Crescent City is African-Americans .