“Base Ball at the Elysian Fields”: Hoboken, New Jersey and the Origins of Modern Baseball by John G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEW JERSEY History GUIDE

NEW JERSEY HISTOry GUIDE THE INSIDER'S GUIDE TO NEW JERSEY'S HiSTORIC SitES CONTENTS CONNECT WITH NEW JERSEY Photo: Battle of Trenton Reenactment/Chase Heilman Photography Reenactment/Chase Heilman Trenton Battle of Photo: NEW JERSEY HISTORY CATEGORIES NEW JERSEY, ROOTED IN HISTORY From Colonial reenactments to Victorian architecture, scientific breakthroughs to WWI Museums 2 monuments, New Jersey brings U.S. history to life. It is the “Crossroads of the American Revolution,” Revolutionary War 6 home of the nation’s oldest continuously Military History 10 operating lighthouse and the birthplace of the motion picture. New Jersey even hosted the Industrial Revolution 14 very first collegiate football game! (Final score: Rutgers 6, Princeton 4) Agriculture 19 Discover New Jersey’s fascinating history. This Multicultural Heritage 22 handbook sorts the state’s historically significant people, places and events into eight categories. Historic Homes & Mansions 25 You’ll find that historic landmarks, homes, Lighthouses 29 monuments, lighthouses and other points of interest are listed within the category they best represent. For more information about each attraction, such DISCLAIMER: Any listing in this publication does not constitute an official as hours of operation, please call the telephone endorsement by the State of New Jersey or the Division of Travel and Tourism. numbers provided, or check the listed websites. Cover Photos: (Top) Battle of Monmouth Reenactment at Monmouth Battlefield State Park; (Bottom) Kingston Mill at the Delaware & Raritan Canal State Park 1-800-visitnj • www.visitnj.org 1 HUnterdon Art MUseUM Enjoy the unique mix of 19th-century architecture and 21st- century art. This arts center is housed in handsome stone structure that served as a grist mill for over a hundred years. -

Download Preview

DETROIT TIGERS’ 4 GREATEST HITTERS Table of CONTENTS Contents Warm-Up, with a Side of Dedications ....................................................... 1 The Ty Cobb Birthplace Pilgrimage ......................................................... 9 1 Out of the Blocks—Into the Bleachers .............................................. 19 2 Quadruple Crown—Four’s Company, Five’s a Multitude ..................... 29 [Gates] Brown vs. Hot Dog .......................................................................................... 30 Prince Fielder Fields Macho Nacho ............................................................................. 30 Dangerfield Dangers .................................................................................................... 31 #1 Latino Hitters, Bar None ........................................................................................ 32 3 Hitting Prof Ted Williams, and the MACHO-METER ......................... 39 The MACHO-METER ..................................................................... 40 4 Miguel Cabrera, Knothole Kids, and the World’s Prettiest Girls ........... 47 Ty Cobb and the Presidential Passing Lane ................................................................. 49 The First Hammerin’ Hank—The Bronx’s Hank Greenberg ..................................... 50 Baseball and Heightism ............................................................................................... 53 One Amazing Baseball Record That Will Never Be Broken ...................................... -

Graphic Designby Rachel Digital Strategy

graphic design by Rachel visual web » banners, headers, landing pages, web graphics • print ads • print collatoral » postcards, business cards, brochures, flyers, menus • content creation for social media & blogs • branding » logo design & identity • wordpress.com set up & management • small business marketing • site analytics • SEO Increase community engagement with and more clicks! digital more fans! more sales! strategy for your business. What’s your digital strategy? www.digitalrachel.com » [email protected] The Pageant Committee Columbus Day Committee Board Joann Rando Fairfield, General Chairman Honorable Commendatore Commendatore Gennaro Consalvo, Esq Gennaro Consalvo, Esquire General Chairman Emeritus Sebastian Cutaia, 1st Vice Chair Executive Producer Nicolle Piergiovanni, 2nd Vice Chair Rosanna Consalvo Sarto Joseph C. Milano, Monuments Chairman Rachel Albanese, Membership Chairman Executive Director Lisa Wilson, Secretary Miss Columbus Day Pageant Theresa Lucarelli, Liason Giulietta Consalvo Honorary Chairman Executive Director Gary Hill Miss Atlantic County Pageant Honorary Trustees Nicolle Tepedino Piergiovanni The Bonnie Blue Foundation Hon. Edmund Colanzi Executive Director Hon. Paul D’Amato, Esq. (A Francesca “Bonnie” Consalvo Memorial) Hon. Frank Formica Miss Southern Counties Hon. William L. Gormley, Esq. Giovanna Consalvo Spina and The Columbus Day Committee of Atlantic City Hon. Lorenzo Langford Hon. Dennis Levinson Producer Hon. William Marsch Hon. James McCullough Becky Norton & Dear Benefactor, Hon. William J. Ross, III Stefanie Tripician Hon. Thomas Russo (Est. Assoc. Executive Directors For 49 years the Columbus Day Committee of Atlantic City Hon. John Schultz and Contestant Coordinators and Inc. 1938 CDC) has been a major scholarship contributor for our Hon. James Whelan Jeff Buscham youth and the Miss America Organization (MAO) - beginning Past General Chairman Comm. -

By Kimberly Parkhurst Thesis

America’s Pastime: How Baseball Went from Hoboken to the World Series An Honors Thesis (HONR 499) by Kimberly Parkhurst Thesis Advisor Dr. Bruce Geelhoed Ball State University Muncie, Indiana April 2020 Expected Date of Graduation July 2020 Abstract Baseball is known as “America’s Pastime.” Any sports aficionado can spout off facts about the National or American League based on who they support. It is much more difficult to talk about the early days of baseball. Baseball is one of the oldest sports in America, and the 1800s were especially crucial in creating and developing modern baseball. This paper looks at the first sixty years of baseball history, focusing especially on how the World Series came about in 1903 and was set as an annual event by 1905. Acknowledgments I would like to thank Carlos Rodriguez, a good personal friend, for loaning me his copy of Ken Burns’ Baseball documentary, which got me interested in this early period of baseball history. I would like to thank Dr. Bruce Geelhoed for being my advisor in this process. His work, enthusiasm, and advice has been helpful throughout this entire process. I would also like to thank Dr. Geri Strecker for providing me a strong list of sources that served as a starting point for my research. Her knowledge and guidance were immeasurably helpful. I would next like to thank my friends for encouraging the work I do and supporting me. They listen when I share things that excite me about the topic and encourage me to work better. Finally, I would like to thank my family for pushing me to do my best in everything I do, whether academic or extracurricular. -

Black History Trivia Bowl Study Questions Revised September 13, 2018 B C D 1 CATEGORY QUESTION ANSWER

Black History Trivia Bowl Study Questions Revised September 13, 2018 B C D 1 CATEGORY QUESTION ANSWER What national organization was founded on President National Association for the Arts Advancement of Colored People (or Lincoln’s Birthday? NAACP) 2 In 1905 the first black symphony was founded. What Sports Philadelphia Concert Orchestra was it called? 3 The novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published in what Sports 1852 4 year? Entertainment In what state is Tuskegee Institute located? Alabama 5 Who was the first Black American inducted into the Pro Business & Education Emlen Tunnell 6 Football Hall of Fame? In 1986, Dexter Gordan was nominated for an Oscar for History Round Midnight 7 his performance in what film? During the first two-thirds of the seventeenth century Science & Exploration Holland and Portugal what two countries dominated the African slave trade? 8 In 1994, which president named Eddie Jordan, Jr. as the Business & Education first African American to hold the post of U.S. Attorney President Bill Clinton 9 in the state of Louisiana? Frank Robinson became the first Black American Arts Cleveland Indians 10 manager in major league baseball for what team? What company has a successful series of television Politics & Military commercials that started in 1974 and features Bill Jell-O 11 Cosby? He worked for the NAACP and became the first field Entertainment secretary in Jackson, Mississippi. He was shot in June Medgar Evers 12 1963. Who was he? Performing in evening attire, these stars of The Creole Entertainment Show were the first African American couple to perform Charles Johnson and Dora Dean 13 on Broadway. -

LACROSSE CURLING >>> CRICKET >>> >>>

FEATURE STORY YAY TEAM! Canada’s favourite sports go back a long way CURLING >>> In 1759, Scottish soldiers melted some cannonballs to make curling “stones” for a match in Quebec City. Formed in 1807, the Montreal Curling Club was the first of its kind outside Scotland. More than 710,000 Canadians curl every year, which might just make it our country’s most popular organized sport. Curling teams in >>> Winnipeg in 1906 CRICKET The first Canadian cricket clubs formed in Toronto in 1827 and St. John’s in 1828 after British soldiers brought it with them. Canada Canada, Archives Library and Commons, Flickr beat the U.S. in 1844 in the world’s first CP Images Canada, Archives Library and international cricket match. In 1867, Sir John A. Macdonald declared cricket Canada’s first national sport. 1869 Canadian lacrosse champions from the Mohawk community of Kahnawake, Que. LACROSSE >>> Canada’s official summer sport comes from a common First Nations game known by the Anishinaabe as bagaa’atowe, and as tewaarathon by the Kanien’kehá:ka. (French priests named it lacrosse in the 1630s.) Games were often used to train warriors, and could involve hundreds of players on a field as long as a kilometre. Non- Indigenous people picked up on the fast, exciting sport in the mid-1800s. William Beers, a Montreal Star Canadian cricketer dentist, wrote down rules for the first time in Amarbir Singh “Jimmy” Hansra September, 1860. 66 KAYAK DEC 2017 GURINDER OSAN, Wiki Commons,Kayak_62.indd 6 2017-11-15 10:02 AM SOCCER >>> More commonly called football in its early life, soccer was considered unladylike from the first days of organized play in the 1870s until well into the 1950s. -

Baseball News Clippings

! BASEBALL I I I NEWS CLIPPINGS I I I I I I I I I I I I I BASE-BALL I FIRST SAME PLAYED IN ELYSIAN FIELDS. I HDBOKEN, N. JT JUNE ^9f }R4$.* I DERIVED FROM GREEKS. I Baseball had its antecedents In a,ball throw- Ing game In ancient Greece where a statue was ereoted to Aristonious for his proficiency in the game. The English , I were the first to invent a ball game in which runs were scored and the winner decided by the larger number of runs. Cricket might have been the national sport in the United States if Gen, Abner Doubleday had not Invented the game of I baseball. In spite of the above statement it is*said that I Cartwright was the Johnny Appleseed of baseball, During the Winter of 1845-1846 he drew up the first known set of rules, as we know baseball today. On June 19, 1846, at I Hoboken, he staged (and played in) a game between the Knicker- bockers and the New Y-ork team. It was the first. nine-inning game. It was the first game with organized sides of nine men each. It was the first game to have a box score. It was the I first time that baseball was played on a square with 90-feet between bases. Cartwright did all those things. I In 1842 the Knickerbocker Baseball Club was the first of its kind to organize in New Xbrk, For three years, the Knickerbockers played among themselves, but by 1845 they I had developed a club team and were ready to meet all comers. -

New Jersey State Research Guide Family History Sources in the Garden State

New Jersey State Research Guide Family History Sources in the Garden State New Jersey History After Henry Hudson’s initial explorations of the Hudson and Delaware River areas, numerous Dutch settlements were attempted in New Jersey, beginning as early as 1618. These settlements were soon abandoned because of altercations with the Lenni-Lenape (or Delaware), the original inhabitants. A more lasting settlement was made from 1638 to 1655 by the Swedes and Finns along the Delaware as part of New Sweden, and this continued to flourish although the Dutch eventually Hessian Barracks, Trenton, New Jersey from U.S., Historical Postcards gained control over this area and made it part of New Netherland. By 1639, there were as many as six boweries, or small plantations, on the New Jersey side of the Hudson across from Manhattan. Two major confrontations with the native Indians in 1643 and 1655 destroyed all Dutch settlements in northern New Jersey, and not until 1660 was the first permanent settlement established—the village of Bergen, today part of Jersey City. Of the settlers throughout the colonial period, only the English outnumbered the Dutch in New Jersey. When England acquired the New Netherland Colony from the Dutch in 1664, King Charles II gave his brother, the Duke of York (later King James II), all of New York and New Jersey. The duke in turn granted New Jersey to two of his creditors, Lord John Berkeley and Sir George Carteret. The land was named Nova Caesaria for the Isle of Jersey, Carteret’s home. The year that England took control there was a large influx of English from New England and Long Island who, for want of more or better land, settled the East Jersey towns of Elizabethtown, Middletown, Piscataway, Shrewsbury, and Woodbridge. -

Sink Or Swim: Deciding the Fate of the Miss America Swimsuit Competition

Volume 4, Issue No. 1. Sink or Swim: Deciding the Fate of the Miss America Swimsuit Competition Grace Slapak Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA ÒÏ Abstract: The Miss America beauty pageant has faced widespread criticism for the swimsuit portion of its show. Feminists claim that the event promotes objectification and oversexualization of contestants in direct contrast to the Miss America Organization’s (MAO) message of progressive female empowerment. The MAO’s position as the leading source of women’s scholarships worldwide begs the question: should women have to compete in a bikini to pay for a place in a cellular biology lecture? As dissent for the pageant mounts, the new head of the MAO Board of Directors, Gretchen Carlson, and the first all-female Board of Directors must decide where to steer the faltering organization. The MAO, like many other businesses, must choose whether to modernize in-line with social movements or whole-heartedly maintain their contentious traditions. When considering the MAO’s long and controversial history, along with their recent scandals, the #MeToo Movement, and the complex world of television entertainment, the path ahead is anything but clear. Ultimately, Gretchen Carlson and the Board of Directors may have to decide between their feminist beliefs and their professional business aspirations. Underlying this case, then, is the question of whether a sufficient definition of women’s leadership is simply leadership by women or if the term and its weight necessitate leadership for women. Will the board’s final decision keep this American institution afloat? And, more importantly, what precedent will it set for women executives who face similar quandaries of identity? In Murky Waters The Miss America Pageant has long occupied a special place in the American psyche. -

Download Article (Pdf)

Vol. 03, No. (2) 2020, Pg. 137-139 Current Research Journal of Social Sciences journalofsocialsciences.org McMichael, Mandy. Miss America’s God: Faith and Identity in America’s Oldest Pageant. Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press, 2019, 249 pp. Dr ELWOOD WATSON (Co-Editor in Chief) Department of History, East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, Tennessee, United States. Article History Published by: 26 November 2020 In Miss America’s God: Faith and Identity in America’s Oldest Pageant, Professor Mandy McMichael deftly provides a concrete narrative of how the frequently complex issues of sex, entertainment, competition, and religion have intersected throughout the pageant’s history in meaningful, contradictory, unpredictable, and complex ways that have provided for a frequently controversial yet riveting annual competition. The author does this within five chapters. McMichael discusses how fierce opposition from the Catholic Church and other religious institutions during the inaugural years of the pageant (1921–1928) culminated in the pageant’s suspension for a few years (in 1929–1932 and 1934). The early years of the pageant were filled with salacious stories of naive young women arriving in Atlantic City only to be seduced and corrupted by unscrupulous men. Similar stories of debauchery continued well into the mid-1930s until pageant officials realized that something had to be done to change the sordid image of the contest. In 1935, the pageant hired Lenora Slaughter, a Southern religious woman who had years of experience in public relations. The decision turned out to be a positive and productive one for the pageant. Slaughter implemented numerous stipulations that were effective in eventually transforming the image of an event that had been largely dismissed as tawdry, earthy, and renegade to one of a contest populated by wholesome, CONTACT Dr Elwood Watson [email protected] Department of History, East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, Tennessee, United States. -

GEM-Fall-2015.Pdf

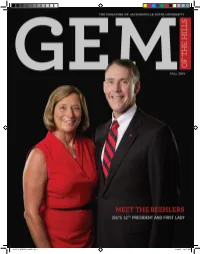

#245-15 GEM Fall 2015.indd 1 9/10/15 10:47 AM : president’s letter DEAR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS, Greetings from Bibb Graves Hall! I university. I look forward to working with am honored to join the Gamecock family you and the entire Gamecock family as we as 12th president of Jacksonville State strive to bring JSU to even greater levels of University. excellence. Thank you for your continued From the first moment I stepped foot support. on the JSU campus, I knew it was a special place. From its beautiful setting and Go Gamecocks! friendly people to its excellent programs and strong traditions – JSU is truly a “GEM” for our state and nation. It is a blessing and a privilege to serve John M. Beehler, Ph.D., CPA you as your president. On page 4, you can President learn more about my background and perspectives on higher education and the GREETINGS GAMECOCKS! It is an exciting time here on campus are happening in your life so we can share as our new freshman class begin their your successes. Thank you for all you do journey as Gamecocks! We hope you will to promote JSU. I hope to hear from you join us for our Halloween Homecoming soon. on Saturday, October 31! The schedule of events is included on page 43. Go Gamecocks! I would like to thank those of you who completed our recent online survey. Your feedback is important to us. I want you to know that we heard you and are looking at ways to incorporate your ideas Kaci Ogle ’95/’04 and suggestions. -

Underground Railroad Routes in New Jersey — 1860 —

Finding Your Way on the Underground Railroad Theme: Cultural & Historical Author: Wilbur H. Siebert adapted by Christine R. Raabe, Education Consultant Subject Areas Vocabulary History/Social Studies, Mathematics, Underground Railroad, slavery, Science emancipation, abolitionist, fugitive, Quaker, freedom, conductor, Duration station master, passenger, North Star, One class period William Still, Harriet Tubman Correlation to NJ Core Curriculum Setting Content Standards Indoors Social Studies Skills 6.3 (1,2,3,4) Interpreting, relating, charting and 6.4 (2,3,4,5,7,8) mapping, identifying, describing, 6.7 (1,5) comparing 6.8 (1) Charting the Course Although not specifically mentioned in the film, the era of the Underground Railroad’s operation did impact the settlement and development of the region and played an important role in the history of New Jersey.” C29 Finding Your Way on the Underground Railroad Objectives many teachers refer to them in to use it rather than risk having Students will their lessons, many instructors a failed fugitive divulge the never relay the regional secrets of the Underground 1. Explain what the significance of these courageous Railroad. Underground Railroad was African-Americans. and why it was important. William Still was born in 1821 Harriet Tubman was known as in Shamong, New Jersey 2. Identify some of the routes of “Moses” for the large number (formerly called Indian Mills — the Underground Railroad on of slaves she guided to freedom Burlington County). Make a map of New Jersey. as a “conductor” on the students aware that this is not far 3. Describe some the conditions Underground Railroad. Tubman from the Bayshore.