Myanmar-NBSAP-2015-2020 Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRENDS in MANDALAY Photo Credits

Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN MANDALAY Photo credits Paul van Hoof Mithulina Chatterjee Myanmar Survey Research The views expressed in this publication are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views of UNDP. Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN MANDALAY UNDP MYANMAR Table of Contents Acknowledgements II Acronyms III Executive Summary 1 1. Introduction 11 2. Methodology 14 2.1 Objectives 15 2.2 Research tools 15 3. Introduction to Mandalay region and participating townships 18 3.1 Socio-economic context 20 3.2 Demographics 22 3.3 Historical context 23 3.4 Governance institutions 26 3.5 Introduction to the three townships participating in the mapping 33 4. Governance at the frontline: Participation in planning, responsiveness for local service provision and accountability 38 4.1 Recent developments in Mandalay region from a citizen’s perspective 39 4.1.1 Citizens views on improvements in their village tract or ward 39 4.1.2 Citizens views on challenges in their village tract or ward 40 4.1.3 Perceptions on safety and security in Mandalay Region 43 4.2 Development planning and citizen participation 46 4.2.1 Planning, implementation and monitoring of development fund projects 48 4.2.2 Participation of citizens in decision-making regarding the utilisation of the development funds 52 4.3 Access to services 58 4.3.1 Basic healthcare service 62 4.3.2 Primary education 74 4.3.3 Drinking water 83 4.4 Information, transparency and accountability 94 4.4.1 Aspects of institutional and social accountability 95 4.4.2 Transparency and access to information 102 4.4.3 Civil society’s role in enhancing transparency and accountability 106 5. -

ED45E Rare and Scarce Species Hierarchy.Pdf

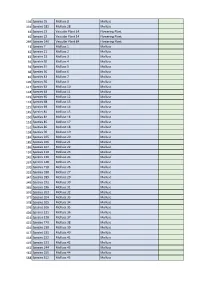

104 Species 55 Mollusc 8 Mollusc 334 Species 181 Mollusc 28 Mollusc 44 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 45 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 269 Species 149 Vascular Plant 84 Flowering Plant 13 Species 7 Mollusc 1 Mollusc 42 Species 21 Mollusc 2 Mollusc 43 Species 22 Mollusc 3 Mollusc 59 Species 30 Mollusc 4 Mollusc 59 Species 31 Mollusc 5 Mollusc 68 Species 36 Mollusc 6 Mollusc 81 Species 43 Mollusc 7 Mollusc 105 Species 56 Mollusc 9 Mollusc 117 Species 63 Mollusc 10 Mollusc 118 Species 64 Mollusc 11 Mollusc 119 Species 65 Mollusc 12 Mollusc 124 Species 68 Mollusc 13 Mollusc 125 Species 69 Mollusc 14 Mollusc 145 Species 81 Mollusc 15 Mollusc 150 Species 84 Mollusc 16 Mollusc 151 Species 85 Mollusc 17 Mollusc 152 Species 86 Mollusc 18 Mollusc 158 Species 90 Mollusc 19 Mollusc 184 Species 105 Mollusc 20 Mollusc 185 Species 106 Mollusc 21 Mollusc 186 Species 107 Mollusc 22 Mollusc 191 Species 110 Mollusc 23 Mollusc 245 Species 136 Mollusc 24 Mollusc 267 Species 148 Mollusc 25 Mollusc 270 Species 150 Mollusc 26 Mollusc 333 Species 180 Mollusc 27 Mollusc 347 Species 189 Mollusc 29 Mollusc 349 Species 191 Mollusc 30 Mollusc 365 Species 196 Mollusc 31 Mollusc 376 Species 203 Mollusc 32 Mollusc 377 Species 204 Mollusc 33 Mollusc 378 Species 205 Mollusc 34 Mollusc 379 Species 206 Mollusc 35 Mollusc 404 Species 221 Mollusc 36 Mollusc 414 Species 228 Mollusc 37 Mollusc 415 Species 229 Mollusc 38 Mollusc 416 Species 230 Mollusc 39 Mollusc 417 Species 231 Mollusc 40 Mollusc 418 Species 232 Mollusc 41 Mollusc 419 Species 233 -

North Okkalapa Township Report

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census YANGON REGION, EASTERN DISTRICT North Okkalapa Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population October 2017 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Yangon Region, Eastern District North Okkalapa Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm October 2017 Figure 1: Map of Yangon Region, showing the townships North Okkalapa Township Figures at a Glance 1 Total Population 333,293 2 Population males 156,340 (46.9%) Population females 176,953 (53.1%) Percentage of urban population 100.0% Area (Km2) 26.7 3 Population density (per Km2) 12,465.3 persons Median age 29.4 years Number of wards 19 Number of village tracts - Number of private households 64,756 Percentage of female headed households 27.2% Mean household size 4.8 persons 4 Percentage of population by age group Children (0 – 14 years) 21.0% Economically productive (15 – 64 years) 72.8% Elderly population (65+ years) 6.2% Dependency ratios Total dependency ratio 37.4 Child dependency ratio 28.8 Old dependency ratio 8.6 Ageing index 29.9 Sex ratio (males per 100 females) 88 Literacy rate (persons aged 15 and over) 97.8% Male 98.9% Female 96.9% People with disability Number Per cent Any form of disability 10,442 3.1 Walking 4,881 1.5 Seeing 4,845 1.5 Hearing 2,620 0.8 Remembering 2,935 0.9 Type of Identity Card (persons aged 10 and over) Number Per cent Citizenship -

Mandalay Region Census Report Volume 3 – L

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Mandalay Region Census Report Volume 3 – l Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Mandalay Region Report Census Report Volume 3 – I For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Figure 2: Map of Mandalay Region, Districts and Townships ii Census Report Volume 3–I (Mandalay) Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014 and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is now my hope that the main results both Union and each of the State and Region reports will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national and sub-national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and officers at the State/Region, District and Township levels and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. -

Ex-Post Evaluation Report on the Hlegu Township Rural Development Project in Myanmar Hlegu Township Rural Development Project in Myanmar

2014 ISBN 978-89-6469-225-7 93320 업무자료 평가심사 2014-37-060 발간등록번호 업무자료 평가심사 2014-37-060 11-B260003-000329-01 Ex-post Evaluation Report on the Ex-post Evaluation Report on the Hlegu Township Rural Development Project in Myanmar Rural Development Township Report on the Hlegu Ex-post Evaluation Hlegu Township Rural Development Project in Myanmar 2013. 12 461-833 경기도 성남시 수정구 대왕판교로 825 Tel.031-7400-114 Fax.031-7400-655 http://www.koica.go.kr Ex-Post Evaluation Report on the Hlegu Township Rural Development Project in Myanmar 2013. 12 The Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) performs various types of evaluation in order to secure accountability and achieve better development results by learning. KOICA conducts evaluations within different phases of projects and programs, such as ex-ante evaluations, interim evaluations, end-of-project evaluations, and ex-post evaluations. Moreover, sector evaluations, country program evaluations, thematic evaluations, and modality evaluations are also performed. In order to ensure the independence of evaluation contents and results, a large amount of evaluation work is carried out by external evaluators. Also, the Evaluation Office directly reports evaluation results to the President of KOICA. KOICA has a feedback system under which planning and project operation departments take evaluation findings into account in programming and implementation. Evaluation reports are widely disseminated to staffs and management within KOICA, as well as to stakeholders both in Korea and partner countries. All evaluation reports published by KOICA are posted on the KOICA website. (www.koica.go.kr) This evaluation study was entrusted to Yeungnam University by KOICA for the purpose of independent evaluation research. -

Passive Citizen Science: the Role of Social Media in Wildlife Observations

Passive citizen science: the role of social media in wildlife observations 1Y* 1Y 1Y Thomas Edwards , Christopher B. Jones , Sarah E. Perkins2, Padraig Corcoran 1 School Of Computer Science and Informatics, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK 2 School of Biosciences, Cardiff University, Cardiff, CF10 3AX YThese authors contributed equally to this work. * [email protected] Abstract Citizen science plays an important role in observing the natural environment. While conventional citizen science consists of organized campaigns to observe a particular phenomenon or species there are also many ad hoc observations of the environment in social media. These data constitute a valuable resource for `passive citizen science' - the use of social media that are unconnected to any particular citizen science program, but represent an untapped dataset of ecological value. We explore the value of passive citizen science, by evaluating species distributions using the photo sharing site Flickr. The data are evaluated relative to those submitted to the National Biodiversity Network (NBN) Atlas, the largest collection of species distribution data in the UK. Our study focuses on the 1500 best represented species on NBN, and common invasive species within UK, and compares the spatial and temporal distribution with NBN data. We also introduce an innovative image verification technique that uses the Google Cloud Vision API in combination with species taxonomic data to determine the likelihood that a mention of a species on Flickr represents a given species. The spatial and temporal analyses for our case studies suggest that the Flickr dataset best reflects the NBN dataset when considering a purely spatial distribution with no time constraints. -

Programs and Field Trips

CONTENTS Welcome from Kathy Martin, NAOC-V Conference Chair ………………………….………………..…...…..………………..….…… 2 Conference Organizers & Committees …………………………………………………………………..…...…………..……………….. 3 - 6 NAOC-V General Information ……………………………………………………………………………………………….…..………….. 6 - 11 Registration & Information .. Council & Business Meetings ……………………………………….……………………..……….………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………………………………..…..……...….. 11 6 Workshops ……………………….………….……...………………………………………………………………………………..………..………... 12 Symposia ………………………………….……...……………………………………………………………………………………………………..... 13 Abstracts – Online login information …………………………..……...………….………………………………………….……..……... 13 Presentation Guidelines for Oral and Poster Presentations …...………...………………………………………...……….…... 14 Instructions for Session Chairs .. 15 Additional Social & Special Events…………… ……………………………..………………….………...………………………...…………………………………………………..…………………………………………………….……….……... 15 Student Travel Awards …………………………………………..………...……………….………………………………..…...………... 18 - 20 Postdoctoral Travel Awardees …………………………………..………...………………………………..……………………….………... 20 Student Presentation Award Information ……………………...………...……………………………………..……………………..... 20 Function Schedule …………………………………………………………………………………………..……………………..…………. 22 – 26 Sunday, 12 August Tuesday, 14 August .. .. .. 22 Wednesday, 15 August– ………………………………...…… ………………………………………… ……………..... Thursday, 16 August ……………………………………….…………..………………………………………………………………… …... 23 Friday, 17 August ………………………………………….…………...………………………………………………………………………..... 24 Saturday, -

SICHUAN (Including Northern Yunnan)

Temminck’s Tragopan (all photos by Dave Farrow unless indicated otherwise) SICHUAN (Including Northern Yunnan) 16/19 MAY – 7 JUNE 2018 LEADER: DAVE FARROW The Birdquest tour to Sichuan this year was a great success, with a slightly altered itinerary to usual due to the closure of Jiuzhaigou, and we enjoyed a very smooth and enjoyable trip around the spectacular and endemic-rich mountain and plateau landscapes of this striking province. Gamebirds featured strongly with 14 species seen, the highlights of them including a male Temminck’s Tragopan grazing in the gloom, Chinese Monal trotting across high pastures, White Eared and Blue Eared Pheasants, Lady Amherst’s and Golden Pheasants, Chinese Grouse and Tibetan Partridge. Next were the Parrotbills, with Three-toed, Great and Golden, Grey-hooded and Fulvous charming us, Laughingthrushes included Red-winged, Buffy, Barred, Snowy-cheeked and Plain, we saw more Leaf Warblers than we knew what to do with, and marvelled at the gorgeous colours of Sharpe’s, Pink-rumped, Vinaceous, Three-banded and Red-fronted Rosefinches, the exciting Przevalski’s Finch, the red pulse of Firethroats plus the unreal blue of Grandala. Our bird of the trip? Well, there was that Red Panda that we watched for ages! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Sichuan Including Northern Yunnan 2018 www.birdquest-tours.com Our tour began with a short extension in Yunnan, based in Lijiang city, with the purpose of finding some of the local specialities including the rare White-speckled Laughingthrush, which survives here in small numbers. Once our small group had arrived in the bustling city of Lijiang we began our birding in an area of hills that had clearly been totally cleared of forest in the fairly recent past, with a few trees standing above the hillsides of scrub. -

Multilocus Phylogeny of the Avian Family Alaudidae (Larks) Reveals

1 Multilocus phylogeny of the avian family Alaudidae (larks) 2 reveals complex morphological evolution, non- 3 monophyletic genera and hidden species diversity 4 5 Per Alströma,b,c*, Keith N. Barnesc, Urban Olssond, F. Keith Barkere, Paulette Bloomerf, 6 Aleem Ahmed Khang, Masood Ahmed Qureshig, Alban Guillaumeth, Pierre-André Crocheti, 7 Peter G. Ryanc 8 9 a Key Laboratory of Zoological Systematics and Evolution, Institute of Zoology, Chinese 10 Academy of Sciences, Chaoyang District, Beijing, 100101, P. R. China 11 b Swedish Species Information Centre, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Box 7007, 12 SE-750 07 Uppsala, Sweden 13 c Percy FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology, DST/NRF Centre of Excellence, 14 University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7700, South Africa 15 d Systematics and Biodiversity, Gothenburg University, Department of Zoology, Box 463, SE- 16 405 30 Göteborg, Sweden 17 e Bell Museum of Natural History and Department of Ecology, Evolution and Behavior, 18 University of Minnesota, 1987 Upper Buford Circle, St. Paul, MN 55108, USA 19 f Percy FitzPatrick Institute Centre of Excellence, Department of Genetics, University of 20 Pretoria, Hatfield, 0083, South Africa 21 g Institute of Pure & Applied Biology, Bahauddin Zakariya University, 60800, Multan, 22 Pakistan 23 h Department of Biology, Trent University, DNA Building, Peterborough, ON K9J 7B8, 24 Canada 25 i CEFE/CNRS Campus du CNRS 1919, route de Mende, 34293 Montpellier, France 26 27 * Corresponding author: Key Laboratory of Zoological Systematics and Evolution, Institute of 28 Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chaoyang District, Beijing, 100101, P. R. China; E- 29 mail: [email protected] 30 1 31 ABSTRACT 32 The Alaudidae (larks) is a large family of songbirds in the superfamily Sylvioidea. -

First Record for the Sunfish Mola Mola (Molidae: Tetradontiformes)

Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Biology & Fisheries Zoology Department, Faculty of Science, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt. ISSN 1110 – 6131 Vol. 23(2): 563- 574 (2019) www.ejabf.journals.ekb.eg First record for the sunfish Mola mola (Molidae: Tetradontiformes) from the Egyptian coasts, Aqaba Gulf, Red Sea, with notes on morphometrics and levels of major skeletal components Mohamed A. Amer1*; Ahmed El-Sadek2; Ahmed Fathallah3; Hamdy A. Omar4 and Mohamed M. Eltoutou4 1-Faculty of Science, Zoology Dept., Marine Biology, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt. 2- Abu Galum Marine Protectorate Area, Nature Conservation Sector, EEAA, Egypt. 3- Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA), Alexandria Branch, Egypt. 4-National Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries, Alexandria, Egypt. * Corresponding author: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: The sunfish Mola mola is recorded for the first time from the Egyptian Received:April 30, 2019 waters at Abu Galum Protectorate Area (South Sinai), Aqaba Gulf, Red Accepted: May 28, 2019 Sea. The present study conducted to give information on morphometric Online: June 3, 2019 characters, anatomy and levels of major elements in skull, vertebrae and _______________ paraxial parts of its skeletal system. These elements comprised Ca, P, Na, K, Mg, S, Cl, Zn and Cu and their levels were estimated. The results Keywords: exhibited that Ca and P were the main components in skull and were the Sunfish most dominant elements in paraxial skeleton in addition to remarkable Mola mola ratios of Na and Cl. Cu was detected with very low ratios only in paraxial Abu Galum skeleton parts. The annuli in examined vertebrae were counted and showed South Sinai that, this fish may be in its second age group. -

Zootaxa, Betadevario Ramachandrani, a New Danionine Genus And

Zootaxa 2519: 31–47 (2010) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2010 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Betadevario ramachandrani, a new danionine genus and species from the Western Ghats of India (Teleostei: Cyprinidae: Danioninae) P. K. PRAMOD1, FANG FANG2, K. REMA DEVI3, TE-YU LIAO2,4, T.J. INDRA5, K.S. JAMEELA BEEVI6 & SVEN O. KULLANDER2,7 1Marine Products Export Development Authority, Sri Vinayaka Kripa, Opp. Ananda shetty Circle, Attavar, Mangalore, Karnataka 575 001, India. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Swedish Museum of Natural History, POB 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden E-mail: [email protected];[email protected]; [email protected] 3Marine Biological Station, Zoological Survey of India, 130, Santhome High Road, Chennai, India 4Department of Zoology, Stockholm University, 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 5Southern Regional Station, Zoological Survey of India, 130, Santhome High Road, Chennai, India 6Department of Zoology, Maharajas College, Ernukalam, India 7Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Betadevario, new genus, with the single species B. ramachandrani, new species, from Karnataka, southwestern India, is closely related to Devario but differs from it in having two pairs of long barbels (vs. two pairs of short or rudimentary barbels, or barbels absent), wider cleithral spot which extends to cover three scales horizontally (vs. covering only one scale in width), long and low laminar preorbital process (vs. absent or a slender pointed spine-like process) along the anterior margin of the orbit, a unique flank colour pattern with a wide dark band along the lower side, bordered dorsally by a wide light stripe (vs. -

First Documented Record of the Ocean Sunfish, Mola Mola

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Stuttgarter Beiträge Naturkunde Serie A [Biologie] Jahr/Year: 2013 Band/Volume: NS_6_A Autor(en)/Author(s): Jawad Laith A. Artikel/Article: First documented record of the ocean sunfish, Mola mola (Linnaeus), from the Sea of Oman, Sultanate of Oman (Teleostei: Molidae) 287-290 Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde A, Neue Serie 6: 287–290; Stuttgart, 30.IV.2013 287 First documented record of the ocean sunfish, Mola mola (Linnaeus), from the Sea of Oman, Sultanate of Oman (Teleostei: Molidae) LAITH A. JAWAD Abstract The first assured record of the ocean sunfish, Mola mola (Linnaeus, 1758), in Omani waters is reported based on a specimen of 1350 mm total length which has stranded on the coast of Quriat City, 120 km north of Muscat, the capital of Oman. Morphometric and meristic data are provided and compared with those of several specimens of this species from other parts of the world. K e y w o r d s : Sea of Oman; Molidae; range extension. Zusammenfassung Der Mondfisch, Mola mola (Linnaeus, 1758), wird zum ersten Mal für Oman bestätigt. Der Nachweis basiert auf einem 1350 mm langen Exemplar, das an der Küste von Quriat City, 120 km nördlich der omanischen Hauptstadt Muscat gestrandet ist. Morphometrische und meristische Daten dieses Exemplares werden gegeben und mit einigen anderen Belegen weltweit verglichen. Contents 1 Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................................287