A Management and Entreprenurial Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Steel in Figures 2017 Table of Contents Foreword

WORLD STEEL IN FIGURES 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD Foreword ...........................................................................................3 This year we are celebrating our 50th anniversary but of course this Celebrating 50 years of the World Steel Association ............................4 publication will largely report on last year 2016. Much has changed in 50 years – back in 1967, the world produced just less than 500 million CRUDE STEEL PRODUCTION tonnes of steel. In 2016, the world produced just over 1,600 million World crude steel production, 1950 to 2016 ........................................7 tonnes. Most of the growth came from new industrialising nations – Top steelmakers, 2016........................................................................8 Brazil, China, India, Iran and Mexico. Major steel-producing countries, 2015 and 2016 .................................9 Steel as a product is so versatile and fundamental to our lives that it is Crude steel production by process, 2016 .......................................... 10 considered essential to economic growth. Consequently, for most of the Continuously-cast steel output, 2014 to 2016 ����������������������������������� 11 past 50 years, the world has been producing increasingly more steel Monthly crude steel production, 2013 to 2016 ����������������������������������� 12 and sometimes more than was actually required – while at the same time, making the product universally affordable and promoting intense STEEL USE competition between its producers. Steel production and use: geographical distribution, 2006 ................. 14 In the global markets we operate in, fierce competition for trade will Steel production and use: geographical distribution, 2016 ................. 15 remain, with the present push to protect domestic markets probably Apparent steel use, 2010 to 2016...................................................... 16 continuing for the next few years. But we believe that it is crucial for Apparent steel use per capita, 2010 to 2016 .................................... -

Coal Mine Methane Country Profiles, June 2015

Disclaimer The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency does not: a) Make any warranty or representation, expressed or implied, with respect to the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the information contained in this report, or that the use of any apparatus, method, or process disclosed in this report may not infringe upon privately owned rights; or b) Assume any liability with respect to the use of, or damages resulting from the use of, any information, apparatus, method, or process disclosed in this report. CMM Country Profiles CONTENTS Units of Conversions .............................................................................................................................................. i Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................................. ii Global Overview at a Glance ................................................................................................................................. ii Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 Purpose of the Report ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Organization of the Report ................................................................................................................................... 2 1 Argentina ...................................................................................................................................................... -

BANKING on CLIMATE CHANGE Fossil Fuel Finance Report Card 2017

Fossil Fuel Finance Report Card 2017 BANKING ON CLIMATE CHANGE Fossil Fuel Finance Report Card 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS DISCLAIMER: The information in this report is not financial advice, investment advice, trading advice or any other advice. 2 INTRODUCTION 26 COAL MINING 50 HUMAN RIGHTS 3 Executive Summary 27 Policy Review and Model Policy 51 Background 4 Introduction 29 CASE STUDY: Peabody Energy — Post-Bankruptcy 52 CASE STUDY: Dakota Access Pipeline — Funding 6 Extreme Fossil Fuels League Table Business as Usual the Black Snake 7 Key Data 30 CASE STUDY: Bank Beware — Poland's Talk on Coal 8 Bank Grades Summary Mining is Bad Business 54 CONCLUSION 10 Methodology 31 Coal Mining League Table 32 Coal Mining Bank Grades 56 APPENDICES 12 EXTREME OIL 56 Appendix 1: Full Grading Criteria 13 Model Extreme Oil Policy 34 COAL POWER 58 Appendix 2: Companies Included 13 Tar Sands: A Make or Break Moment 35 Policy Review and Model Policy 65 Appendix 3: Calculation of Segment Adjusters 15 CASE STUDY: Keystone XL — No Means No 37 CASE STUDY: Coal Power Expansion Plans Slow in 16 CASE STUDY: Doing “Whatever it Takes” to Vietnam, But Banks Haven’t Gotten the Memo 66 ENDNOTES Stop the Trans Mountain Pipeline 38 CASE STUDY: Western Banks Backing Major Coal Plant 17 Tar Sands League Table Expansion Plans in the Philippines 18 Drilling in Ultra-Deep Waters 39 Coal Mining League Table 19 Ultra-Deepwater Oil League Table 40 Coal Mining Bank Grades THIS REPORT WAS WRITTEN IN COLLABORATION WITH: 20 Arctic Drilling: Still Off Limits 21 Arctic Oil League Table 42 LIQUEFIED NATURAL GAS EXPORT (LNG) 350.org Last Real Indians Bold Alliance Les Amis de la Terre France 22 Forecasting Failure 43 Background and Model Policy CHANGE Market Forces CoalSwarm Mazaska Talks 24 Extreme Oil Bank Grades 44 CASE STUDY: Resisting a Web of Fracking-Pipeline-LNG DivestInvest Individual MN350 Earthworks People & Planet Pollution FairFin Re:Common Friends of the Earth Scotland Save RGV from LNG 46 CASE STUDY: Rio Grande Valley Friends of the Earth U.S. -

Fushun Four Page

FUSHUN MINING GROUP CO., LTD. L IAONING PROVINCE Opportunities for Investment in Coal Mine Methane Projects A major coal producer, the Fushun Mining Group Company, Ltd. has one producing underground mine and one open-pit mine. Total coal production in the mining area is about 6 million tonnes of coal annually. The underground mine, Laohutai, drains about 100 million cubic meters (more than 3.5 billion cubic feet) of methane annually, and methane production from surface boreholes has also begun. Significant opportunity exists for expanding recovery and utilization of methane from surface and underground boreholes. The Fushun Mining Group Company, Ltd. seeks investment for expanding the production of methane from surface boreholes and combining it with a portion of the methane recovered from the Laohutai mine to meet the energy needs of the nearby city of Shenyang. Fushun Mining Group seeks investment from China and abroad to for the proposed coal mine methane development project described in this brochure. OVERVIEW OF THE FUSHUN MINING GROUP COMPANY LTD. CHINA Fushun Mining Area LIAONING The Fushun Mining Group Company Ltd. (informally known as the Fushun Mining Group) is a large state-owned coal enterprise with 26 subsidiaries. Located in the city of Fushun in northeastern China’s Liaoning Province, it is about 45 km from Shenyang, the capital of the province, and 126 km from Anshan, a major iron and steel manufacturing center. Although the Fushun area has produced coal for more than 100 years, an estimated 800 million tonnes of recoverable reserves remain. The Fushun Mining Group has total assets of 4.7 billion yuan ($US 566 million). -

World Steel Market

Confidential For the particpants. World Steel Market May, 2017 0 Confidential Introduction of NSSMC 1 Confidential Corporate History CY1857 CY1897 Japan’s first blast furnace went Sumitomo Cooper Plant was into Operation at Kamaishi. established. <Corporate’s inauguration> CY1901 CY1912 The state-owned Yawata Steel Japan’s first private company Works began operation. started manufacturing cold- CY1970 drawn seamless steel pipes. Yawata Iron & Steel and Fuji CY1949 Iron & Steel merged to from Shin-Fuso Metal Industries, Ltd. Nippon Steel Corporation. been established. <Corporate’s foundation> CY2002 Announced alliances among NSC and SMI, Kobe Steel CY2011 Agreed to commence consideration of merger October 1, 2012 2 Confidential Overview of NSSMC NIPPON STEEL & SUMITOMO METAL CORPORATION Trade Name “NSSMC” Representative Director, Chairman and CEO Shoji MUNEOKA Representative Representative Director, President and COO Hiroshi TOMONO L o c a t i o n of H e a d O f f i c e Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan Foundation Day October 1, 2012 Steelmaking and steel fabrication / Engineering / B u s i n e s s Chemicals / New materials / System solutions Stated Capital 419.5 bn yen Fiscal Year End March 31 3 Confidential The World Top-Ten Players by Crude Steel Production unit:millions of tonnes 2002 2007 2011 2014 2015 vs 2013 vs 2014 1 Arcelor (EU) 44 1 ArcelorMittal (EU) 116 1 ArcelorMittal (EU) 97 1 ArcelorMittal (EU) 98 +2% → 1 ArcelorMittal (EU) 97 -1% 2 LNM Group (EU) 35 2 Nippon Steel (JPN) 36 2 Hebei Group (CHN) 44 2 NSSMC (JPN) 49 -2% ↑ 2 Hesteel -

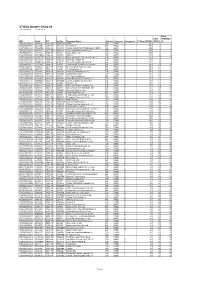

STOXX Greater China 80 Last Updated: 01.08.2017

STOXX Greater China 80 Last Updated: 01.08.2017 Rank Rank (PREVIOU ISIN Sedol RIC Int.Key Company Name Country Currency Component FF Mcap (BEUR) (FINAL) S) TW0002330008 6889106 2330.TW TW001Q TSMC TW TWD Y 113.9 1 1 HK0000069689 B4TX8S1 1299.HK HK1013 AIA GROUP HK HKD Y 80.6 2 2 CNE1000002H1 B0LMTQ3 0939.HK CN0010 CHINA CONSTRUCTION BANK CORP H CN HKD Y 60.5 3 3 TW0002317005 6438564 2317.TW TW002R Hon Hai Precision Industry Co TW TWD Y 51.5 4 4 HK0941009539 6073556 0941.HK 607355 China Mobile Ltd. CN HKD Y 50.8 5 5 CNE1000003G1 B1G1QD8 1398.HK CN0021 ICBC H CN HKD Y 41.3 6 6 CNE1000003X6 B01FLR7 2318.HK CN0076 PING AN INSUR GP CO. OF CN 'H' CN HKD Y 32.0 7 9 CNE1000001Z5 B154564 3988.HK CN0032 BANK OF CHINA 'H' CN HKD Y 31.8 8 7 KYG217651051 BW9P816 0001.HK 619027 CK HUTCHISON HOLDINGS HK HKD Y 31.1 9 8 HK0388045442 6267359 0388.HK 626735 Hong Kong Exchanges & Clearing HK HKD Y 28.0 10 10 HK0016000132 6859927 0016.HK 685992 Sun Hung Kai Properties Ltd. HK HKD Y 20.6 11 12 HK0002007356 6097017 0002.HK 619091 CLP Holdings Ltd. HK HKD Y 20.0 12 11 CNE1000002L3 6718976 2628.HK CN0043 China Life Insurance Co 'H' CN HKD Y 20.0 13 13 TW0003008009 6451668 3008.TW TW05PJ LARGAN Precision TW TWD Y 19.7 14 15 KYG2103F1019 BWX52N2 1113.HK HK50CI CK Property Holdings HK HKD Y 18.3 15 14 CNE1000002Q2 6291819 0386.HK CN0098 China Petroleum & Chemical 'H' CN HKD Y 16.4 16 16 HK0823032773 B0PB4M7 0823.HK B0PB4M Link Real Estate Investment Tr HK HKD Y 15.4 17 19 HK0883013259 B00G0S5 0883.HK 617994 CNOOC Ltd. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Form SD Echostar Corporation

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form SD Specialized Disclosure Report EchoStar Corporation (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Nevada 001-33807 26-1232727 (State or Other Jurisdiction of Incorporation or (Commission File Number) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) Organization) 100 Inverness Terrace East, Englewood, Colorado 80112-5308 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) Dean A. Manson Executive Vice President, General Counsel and Secretary (303) 706-4000 (Name and telephone number, including area code, of person to contact in connection with this report) Check the appropriate box to indicate the rule pursuant to which this form is being filed, and provide the period to which the information in this form applies: x Rule 13p-1 under the Securities Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13p-1) for the reporting period from January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2014. SECTION 1—CONFLICT MINERALS DISCLOSURE ITEM 1.01. Conflict Minerals Disclosure and Report Conflict Minerals Disclosure This Specialized Disclosure Report on Form SD (“Form SD”) of EchoStar Corporation (the “Company”) is filed pursuant to Rule 13p-1 (the “Rule”) promulgated under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended, for the reporting period of January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2014. The Rule was adopted by the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) to implement reporting and disclosure requirements related to certain specified minerals as directed by the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010. The specified minerals are gold, columbite-tantalite (coltan), cassiterite and wolframite, including their derivatives, which are limited to tantalum, tin and tungsten (the “Conflict Minerals”). -

2016 Top 250 International Contractors – Subsidiaries by Rank Rank Company Subsidiary Rank Company Subsidiary

Overview p. 38 // International Market Analysis p. 38 // Past Decade’s International Contracting Revenue p. 38 // International Region Analysis p. 39 // 2015 Revenue Breakdown p. 39 // 2015 New Contracts p. 39 // Domestic Staff Hiring p. 39 // International Staff Hiring p. 39 // Profit-Lossp. 40 // 2015 Backlog p. 40 // Top 10 by Region p. 40 // Top 10 by Market p. 41 // Top 20 Non-U.S. International Construction/Program Managers p. 42 // Top 20 Non-U.S. Global Construction/Program Managers p. 42 // VINCI Builds a War Memorial p. 43 // How Contractors Shared the 2015 Market p. 44 // How To Read the Tables p. 44 // Top 250 International Contractors List p. 45 // International Contractors Index p. 50 // Top 250 Global Contractors List p. 53 // Global Contractors Index p. 58 THE FALCON EMERGES Turkey’s Polimeks is building the NUMBER 40 $2.3-billion Ashgabot International Airport in Turkmenistan. The terminal shape is based on a raptor species. PHOTO COURTESY OF POLIMAEKS INSAATTAAHUT VE SAN TIC. AS TIC. VE SAN OF POLIMAEKS INSAATTAAHUT PHOTO COURTESY International Contractors Seeking Stable Markets Political and economic uncertainty in several regions have global firms looking for markets that are reliable and safe By Peter Reina and Gary J. Tulacz enr.com August 22/29, 2016 ENR 37 0829_Top250_Cover_1.indd 37 8/22/16 3:52 PM THE TOP 250 INTERNATIONAL CONTRACTORS 27.9% Transportation $139,563.9 22.9% Petroleum 21.4% Int’l Market Analysis $114,383.2 Buildings $106,839.6 (Measured $ millions) 10.8% Power $54,134.5 6.0% Other 2.2% 4.1% $29,805.5 0.8% Manufacturing Industrial Telecom $10,808.9 $20,615.7 $ 4,050.5 2.8% 0.2% 1.0% Water Hazardous Sewer/Waste $13,876.8 Waste $4,956.0 $1,210.5 SOURCE: ENR DATA. -

1 1 China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation 1913182 70713

2011 Ranking 2010 Company Name Revenue (RMB, million) Net profit (RMB Million) Rankings (x,000,000) (x,000,000) 1 1 China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation 1913182 70713 2 2 China National Petroleum Corporation 1465415 139871 3 3 China Mobile Limited 485231 119640 China Mobile Revenue: 485,231,000,000 4 5 China Railway Group Limited 473663 7488 5 4 China Railway Construction Corporation Limited 470159 4246 6 6 China Life Insurance Co., Ltd. 388791 33626 7 7 Bank of China Ltd 380821 165156 8 9 China Construction Company Limited 370418 9237 9 8 China Construction Bank Corporation 323489 134844 10 17 Shanghai Automotive Group Co., Ltd. 313376 13698 11 . Agricultural Bank of China Co., Ltd. 290418 94873 12 10 China Bank 276817 104418 China Communications Construction Company 13 11 Limited 272734 9863 14 12 China Telecom Corporation Limited 219864 15759 China Telecom 15 13 China Metallurgical Co., Ltd. 206792 5321 16 15 Baoshan Iron & Steel Co., Ltd. 202413 12889 17 16 China Ping An Insurance (Group) Co., Ltd. 189439 17311 18 21 China National Offshore Oil Company Limited 183053 54410 19 14 China Unicom Co., Ltd. 176168 1228 China Unicom 20 19 China PICC 154307 5212 21 18 China Shenhua Energy Company Limited 152063 37187 22 20 Lenovo Group Limited 143252 1665 Lenovo 23 22 China Pacific Insurance (Group) Co., Ltd. 141662 8557 24 23 Minmetals Development Co., Ltd. 131466 385 25 24 Dongfeng Motor Group Co., Ltd. 122395 10981 26 29 Aluminum Corporation of China 120995 778 27 25 Hebei Iron and Steel Co., Ltd. 116919 1411 28 68 Great Wall Technology Co., Ltd. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2007 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 45 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 48 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 51 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 58 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 62 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2007 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member BoD Board of Directors Cdr. Commander CEO Chief Executive Officer Chp. Chairperson COO Chief Operating Officer CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep.Cdr. Deputy Commander Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson Hon.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

CITIGROUP GLOBAL MARKETS HOLDINGS INC. (The Issuer)

Dated as of 2 December 2014 - NOTICE - CITIGROUP GLOBAL MARKETS HOLDINGS INC. (the Issuer) Relating to certain issues of Participation Certificates issued under the Warrant Programme The Participation Certificates listed below (the Certificates) are issued under the Warrant Programme of Citigroup Global Markets Holdings Inc. and are issued pursuant to a Master Warrant Agreement dated 25 February 2003 (as supplemented and/or amended and/or replaced from time to time) among the Issuer, Citigroup Global Markets Deutschland AG & Co. KGaA as Principal Warrant Agent and New York Warrant Agent (formerly Citibank AG) and the other parties named therein. Notice is hereby given to the holders of the Certificates that with effect on and from 2 December 2014, the Exercise Period in respect of each issue of Certificates has been extended to (and including) 15 January 2016 (the Extended Exercise Period). Holders of the Certificates should note that Automatic Exercise of the Certificates will consequently not occur on the last Business Day of the Exercise Period (as extended by a notice dated 20 November 2010 or 15 November 2013, as the case may be, and specified below) (the Second Expiration Date) but will instead only occur on the last Business Day of the Extended Exercise Period. Terms used in this notice shall be as defined in the Conditions of the relevant Certificates. This modification to the Conditions of the Certificates is made pursuant to Condition 9 (D) of the Certificates. Second Expiration Name ISIN Date Underlying Name CGMHI-CPC KERUI -

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 3 Corporate Profile (Continued)

Contents Corporate Profile 2 Summary of Accounting Figures and Financial Indicators 8 Chairman’s Statement 13 Report of the Directors 26 Report of the Supervisory Committee 35 Discussion and Analysis of Operations 37 Significant Events 73 Movement in Share Capital and Shareholders’ Profile 109 Information on Directors, Supervisors, Senior 123 Management and Employees Corporate Governance 137 Annual General Meeting 171 Audit Report 172 Five-Year Summary 364 Other Relevant Corporate Information 365 Definitions 366 Documents Available for Inspection 368 Corporate Profile The Board, the Supervisory Committee, the Directors, the Supervisors and the senior management of the Company guarantee the truthfulness, accuracy, and completeness of the contents of this report, and that there is no false representation or misleading statement contained in, or material omission from this report, and severally and jointly undertake the legal liability for it. Mr. Wang Yidong, the Company’s Chairman and the person in charge, Mr. Ma Lianyong, Chief Accountant and Mr. Gong Jin, the person in charge of the accounting institution, guarantee the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of the financial report in this report. CORPORATE PROFILE The Company is a joint stock limited company established on 8 May 1997 with Angang Holding as its sole promoter. Pursuant to the reorganization, subsidiaries of the promoter, namely the Cold Roll Plant, Wire Rod Plant and Heavy Plate Plant were transferred to the Company, with a net asset value of RMB2,028,817,600 as determined by the State-owned Assets Administration Bureau, and 1,319,000,000 domestic state-owned legal person shares with a par value of RMB1 each were issued to Angang Holding.