Conservation Nation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dog Lane Café @ Storrs Center Og Lane Café Is Scheduled to Open in the Menu at Dog Lane Café Will Be Modeled Storrs, CT Later This Year

Entertainment & Stuff Pomfret, Connecticut ® “To Bean or not to Bean...?” #63 Volume 16 Number 2 April - June 2012 Free* More News About - Dog Lane Café @ Storrs Center og Lane Café is scheduled to open in The menu at Dog Lane Café will be modeled Storrs, CT later this year. Currently, we are after The Vanilla Bean Café, drawing on influ- D actively engaged in the design and devel- ences from Panera Bread, Starbucks and Au Bon opment of our newest sister restaurant. Our Pain. Dog Lane Café will not be a second VBC kitchen layout and logo graphic design are final- but will have much of the same appeal. The ized. One Dog Lane is a brand new build- breakfast menu will consist of made to ing and our corner location has order omelets and breakfast sand- plenty of windows and a southwest- wiches as well as fresh fruit, ern exposure. Patios on both sides muffins, bagels, croissants, yogurt will offer additional outdoor seating. and other healthy selections to go. Our interior design incorporates Regular menu items served through- wood tones and warm hues for the out the day will include sandwiches, creation of a warm and inviting salads, and soups. Grilled chicken, atmosphere. Artistic style will be the hamburgers, hot dogs and vegetarian highlight of our interior space with options will be served daily along with design and installation by JP Jacquet. His art- chili, chowder and a variety of soups, work is also featured in The Vanilla Bean Café - a desserts and bakery items. Beverage choices will four panel installation in the main dining room - include smoothies, Hosmer Mountain Soda, cof- and in 85 Main throughout the design of the bar fee and tea. -

Diabetes Voices

DIABETES VOICES Issue 14 • September 2015 Diabetes Voices speak out Hello about rise in amputations In this edition of Sixteen Diabetes Voices travelled Diabetes Voices: to Westminster on Wednesday, 15 July to highlight the issue of • Read about how Diabetes diabetes-related amputations. Voices have been raising 135 shoes were displayed awareness of amputation rates. outside Parliament to represent the number of diabetes-related • Find out about Diabetes Voices amputations being carried out making contact with new MPs each week in England. after the election. The rising number of amputations • Get updates on Diabetes UK’s is a huge concern. Diabetes current campaigns. Voices who have had an amputation met with their MPs to • Read 60 seconds with… discuss how it has impacted their Janet Richards outside the Houses of Parliament Vivienne Ruddock from London. lives and what needs to be done. Following on from the event, several MPs have supported the Keep up to date campaign by asking questions in For up-to-date information Parliament and calling on Jeremy about current opportunities to Hunt, Secretary of State for get involved, check the Take Health, to take urgent action. Action noticeboard online at Janet Richards from Croydon had her right leg amputated below www.diabetes.org.uk/ the knee in January 2006. She came to help get the message get_involved/campaigning/ across to healthcare professionals about foot complications diabetes-voices related to diabetes: “I was so glad that I could articulate exactly what I have felt so passionately about over the last ten years. My heart feels a lot Get in touch lighter because I know that doctors and podiatrists will now have heard The Diabetes Voices team the message we were trying to get across.” is here to help you. -

View Call List PDF File 0.07 MB

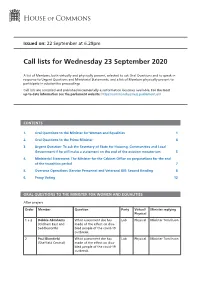

Issued on: 22 September at 6.28pm Call lists for Wednesday 23 September 2020 A list of Members, both virtually and physically present, selected to ask Oral Questions and to speak in response to Urgent Questions and Ministerial Statements; and a list of Members physically present to participate in substantive proceedings. Call lists are compiled and published incrementally as information becomes available. For the most up-to date information see the parliament website: https://commonsbusiness.parliament.uk/ CONTENTS 1. Oral Questions to the Minister for Women and Equalities 1 2. Oral Questions to the Prime Minister 4 3. Urgent Question: To ask the Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government if he will make a statement on the end of the eviction moratorium 5 4. Ministerial Statement: The Minister for the Cabinet Office on preparations for the end of the transition period 7 5. Overseas Operations (Service Personnel and Veterans) Bill: Second Reading 8 6. Proxy Voting 12 ORAL QUESTIONS TO THE MINISTER FOR WOMEN AND EQUALITIES After prayers Order Member Question Party Virtual/ Minister replying Physical 1 + 2 Debbie Abrahams What assessment she has Lab Physical Minister Tomlinson (Oldham East and made of the effect on disa- Saddleworth) bled people of the covid-19 outbreak. 2 Paul Blomfield What assessment she has Lab Physical Minister Tomlinson (Sheffield Central) made of the effect on disa- bled people of the covid-19 outbreak. 2 Call lists for Wednesday 23 September 2020 Order Member Question Party Virtual/ Minister replying Physical 3 Caroline Nokes Supplementary Con Physical Minister Tomlinson (Romsey and Southampton North) 4 + 5 Claire Coutinho (East What steps she is taking to Con Physical Minister Badenoch + 6 Surrey) encourage girls and young women to take up STEM subjects. -

Press Release Wednesday 29 August 2018 Further Cast

PRESS RELEASE WEDNESDAY 29 AUGUST 2018 FURTHER CAST ANNOUNCED FOR DEBRIS STEVENSON’S NEW WORK POET IN DA CORNER, DIRECTED BY OLA INCE OPENING IN THE JERWOOD THEATRE DOWNSTAIRS FRIDAY 21 SEPTEMBER 2018. New trailer here. Downloadable artwork here. Listen to a track Kemi from the show here. Left to right back row: Jammz, Debris Stevenson and Mikey ‘J’ Asante. Left to right front row: Kirubel Belay and Cassie Clare. Photo credit: Romany-Francesca Mukoro In the semi-autobiographical Poet in da Corner poet, lyricist, and dancer Debris Stevenson explores how grime helped shape her youth. Debris and previously announced writer and performer Jammz will be joined by Cassie Clare and Kirubel Belay. Directed by Ola Ince, Poet in da Corner will also feature music and composition from Michael ‘Mikey J’ Asante, co-founder and co-artistic director of Boy Blue. The production runs Friday 21 September 2018 – Saturday 6 October 2018 with press in from 7.30pm Tuesday 25 September 2018. In a strict Mormon household somewhere in the seam between East London and Essex, a girl is given Dizzee Rascal’s ground-breaking grime album Boy in da Corner by her best friend SS Vyper. Precisely 57 minutes and 21 seconds later, her life begins to change – from feeling muted by dyslexia to spitting the power of her words; from being conflicted about her sexuality to finding the freedom to explore; from feeling alone to being given the greatest gift by her closest friend. A coming of age story inspired by Dizzee Rascal’s seminal album, Boy in da Corner. -

General Election 2015 Results

General Election 2015 Results. The UK General Election was fought across all 46 Parliamentary Constituencies in the East Midlands on 7 May 2015. Previously the Conservatives held 30 of these seats, and Labour 16. Following the change of seats in Corby and Derby North the Conservatives now hold 32 seats and Labour 14. The full list of the regional Prospective Parliamentary Candidates (PPCs) is shown below with the elected MP is shown in italics; Amber Valley - Conservative Hold: Stuart Bent (UKIP); John Devine (G); Kevin Gillott (L); Nigel Mills (C); Kate Smith (LD) Ashfield - Labour Hold: Simon Ashcroft (UKIP); Mike Buchanan (JMB); Gloria De Piero (L); Helen Harrison (C); Philip Smith (LD) Bassetlaw - Labour Hold: Sarah Downs (C); Leon Duveen (LD); John Mann (L); David Scott (UKIP); Kris Wragg (G) Bolsover - Labour Hold: Peter Bedford (C); Ray Calladine (UKIP); David Lomax (LD); Dennis Skinner (L) Boston & Skegness - Conservative Hold: Robin Hunter-Clarke (UKIP); Peter Johnson (I); Paul Kenny (L); Lyn Luxton (TPP); Chris Pain (AIP); Victoria Percival (G); Matt Warman (C); David Watts (LD); Robert West (BNP). Sitting MP Mark Simmonds did not standing for re-election Bosworth - Conservative Hold: Chris Kealey (L); Michael Mullaney (LD); David Sprason (UKIP); David Tredinnick (C) Broxtowe - Conservative Hold: Ray Barry (JMB); Frank Dunne (UKIP); Stan Heptinstall (LD); David Kirwan (G); Nick Palmer (L); Anna Soubry (C) Charnwood - Conservative Hold: Edward Argar (C); Cathy Duffy (BNP); Sean Kelly-Walsh (L); Simon Sansome (LD); Lynton Yates (UKIP). Sitting MP Stephen Dorrell did not standing for re- election Chesterfield - Labour Hold: Julia Cambridge (LD); Matt Genn (G); Tommy Holgate (PP); Toby Perkins (L); Mark Vivis (C); Matt Whale (TUSC); Stuart Yeowart (UKIP). -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

LAW REVMV Volume 25 Fall 1997 Number 1

NORTHERN KENTUCKY LAW REVMV Volume 25 Fall 1997 Number 1 Natural Resource and Environmental Law Issue ARTICLES Smog, Science & the EPA ............................................... Kevin D. Hill 1 Overview of Brownfield Redevelopment Initiatives: A Renaissance in the Traditional Command and Control Approach to Environmental Protection ................ Philip J. Schworer 29 American Mining Congress v. Army Corps of Engineers:Ignoring Chevron and the Clean Water Act's Broad Purposes ......................... BradfordC. Mank 51 SPECIAL ESSAY Comparative Risk Assessment and Environmental Priorities Projects: A Forum, Not a Formula ........................................ John S. Applegate 71 PRACTITIONER'S GUIDE The Use of Experts in Environmental Litigation: A Practitioner's Guide .................................. Kim K Burke 111 NOTE United States v. Ahmad: What You Don't Know Won't Hurt You. Or Will It? .................. MichaelE.M. Fielman 141 Special Feature Introduction to the Best Petitioner and Respondent Briefs from the Fifth Annual Salmon P. Chase College of Law Environmental Law Moot Court Competition ............................ M. PatiaR. Tabar 163 M oot Court Problem ....................................................................... 165 Best Brief, Petitioner ............................... University of Cincinnati 181 Best Brief, Respondent .............................. University of Wisconsin 209 ARTICLES SMOG, SCIENCE & THE EPA by Kevin D. Hill' The yellow fog that rubs its back upon the window-panes The yellow -

Download (9MB)

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 2018 Behavioural Models for Identifying Authenticity in the Twitter Feeds of UK Members of Parliament A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF UK MPS’ TWEETS BETWEEN 2011 AND 2012; A LONGITUDINAL STUDY MARK MARGARETTEN Mark Stuart Margaretten Submitted for the degree of Doctor of PhilosoPhy at the University of Sussex June 2018 1 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................ 1 DECLARATION .................................................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................... 6 TABLES ............................................................................................................................................ -

Taunton Deane MP Rebecca Pow Pledges Support for 'Love Your

Taunton Deane MP Rebecca Pow pledges support for ‘Love Your Railway Campaign’ & West Somerset Railway August 9, 2021 Taunton Deane MP Rebecca Pow has lent her support to the national ‘Love Your Railway’ campaign. The campaign aims to shine a spotlight on the important work heritage railways do for historic conservation, education, and research. The campaign also highlights the detrimental impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had on the nation’s heritage railways. The 22-mile-long West Somerset Railway (WSR) starts in Bishops Lydeard in MP Rebecca Pow’s constituency of Taunton Deane and runs through to Minehead and is one of the most popular tourist attractions in the area. Taunton Deane MP Rebecca Pow said: “The ‘Love Your Railway’ campaign across the country is a great example of the nation’s heritage railways working together to highlight what they do so well in conserving the past for current and future generations to enjoy, and it deserves support. “The West Somerset Railway (WSR) is the longest heritage line in England and is one of our unique local attractions; keeping it up and running is important to all those who love it as well as the local economy. Starting at Bishops Lydeard and finishing at Minehead, the heritage line passes through some of our most beautiful countryside, including the Quantock Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty before passing along the Bristol Channel Coast. “I welcome the substantial initial grant from DCMS of just under £865,000 (from the Cultural Recovery Fund), to help maintain the enterprise, however it was disappointing that the second application for funding has been unsuccessful. -

![Clean Air (Human Rights) Bill [HL]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2064/clean-air-human-rights-bill-hl-1062064.webp)

Clean Air (Human Rights) Bill [HL]

Clean Air (Human Rights) Bill [HL] CONTENTS 1Overview 2 Reviewing and revising the pollutants and limits in Schedules 1 to 4 3 Secretary of State’s duty: assessing air pollutants 4 Secretary of State’s duty: additional provisions 5Environment Agency 6 Committee on Climate Change 7 Local authorities 8 Civil Aviation Authority 9 Highways England 10 Historic England 11 Natural England 12 The establishment of the Citizens’ Commission for Clean Air 13 Judicial review and other legal proceedings 14 Duty to maintain clear air: assessment 15 Duty to maintain clean air: reporting 16 Environmental principles 17 Interpretation 18 Extent, commencement and short title Schedule 1 — Pollutants relating to local and atmospheric pollution Schedule 2 — Indoor air pollutants Schedule 3 — Pollutants causing primarily environmental harm Schedule 4 — Pollutants causing climate change Schedule 5 — The Protocols to the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe’s Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution Schedule 6 — The clean air enactments Schedule 7 — Constitution of the Citizens’ Commission for Clean Air HL Bill 17 58/1 Clean Air (Human Rights) Bill [HL] 1 A BILL TO Establish the right to breathe clean air; to require the Secretary of State to achieve and maintain clean air in England and Wales; to involve Public Health England in setting and reviewing pollutants and their limits; to enhance the powers, duties and functions of the Environment Agency, the Committee on Climate Change, local authorities (including port authorities), the Civil Aviation Authority, Highways England, Historic England and Natural England in relation to air pollution; to establish the Citizens’ Commission for Clean Air with powers to institute or intervene in legal proceedings; to require the Secretary of State and the relevant national authorities to apply environmental principles in carrying out their duties under this Act and the clean air enactments; and for connected purposes. -

Tackling Air Pollution in China—What Do We Learn from the Great Smog of 1950S in LONDON

Sustainability 2014, 6, 5322-5338; doi:10.3390/su6085322 OPEN ACCESS sustainability ISSN 2071-1050 www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability Article Tackling Air Pollution in China—What do We Learn from the Great Smog of 1950s in LONDON Dongyong Zhang 1,2, Junjuan Liu 1 and Bingjun Li 1,* 1 College of Information and Management Science, Henan Agricultural University, 15 Longzi Lake Campus, Zhengzhou East New District, Zhengzhou, Henan 450046, China; E-Mails: [email protected] (D.Z.); [email protected] (J.L.) 2 Center for International Earth Science Information Network, The Earth Institute, Columbia University, P.O. Box 1000 (61 Route 9W), Palisades, NY 10964, USA * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-371-6355-8101. Received: 10 June 2014; in revised form: 21 July 2014 / Accepted: 29 July 2014 / Published: 18 August 2014 Abstract: Since the prolonged, severe smog that blanketed many Chinese cities in first months of 2013, living in smog has become “normal” to most people living in mainland China. This has not only caused serious harm to public health, but also resulted in massive economic losses in many other ways. Tackling the current air pollution has become crucial to China’s long-term economic and social sustainable development. This paper aims to find the causes of the current severe air quality and explore the possible solutions by reviewing the current literature, and by comparing China’s air pollution regulations to that of the post London Killer Smog of 1952, in the United Kingdom (UK). -

Item 3 Glasgow City Council 24Th January 2013 Executive Committee

Item 3 Glasgow City Council 24th January 2013 Executive Committee Report by Councillor Archie Graham, Depute Leader of the Council Contact: Annemarie O’Donnell, Executive Director of Corporate Services, Ext: 74522 PROPOSAL TO PROMOTE A PRIVATE BILL IN RELATION TO THE BURRELL COLLECTION Purpose of Report: To seek approval from the Executive Committee to promote a private bill in order to lift the restriction on overseas lending of the Burrell Collection. Recommendations: The Executive Committee is asked to: 1. Approve the promotion of a private bill in order to lift the restriction on overseas lending of the Burrell Collection; and 2. Refer this matter to the Council for approval in accordance with Standing Orders and s82 of the Local Government (Scotland ) Act 1973 Ward No(s): Citywide: 9 Local member(s) advised: Yes No consulted: Yes No PLEASE NOTE THE FOLLOWING: Any Ordnance Survey mapping included within this Report is provided by Glasgow City Council under licence from the Ordnance Survey in order to fulfil its public function to make available Council-held public domain information. Persons viewing this mapping should contact Ordnance Survey Copyright for advice where they wish to licence Ordnance Survey mapping/map data for their own use. The OS web site can be found at <http://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk> " If accessing this Report via the Internet, please note that any mapping is for illustrative purposes only and is not true to any marked scale 1. THE BURRELL COLLECTION 1.1 Sir William Burrell (1861 – 1958) was a Glaswegian shipping magnate who combined his business acumen with collecting art.