Études Asiatiques

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Slumdog Millionaire Vikas Swarup

slumdog millionaire Vikas Swarup’s spectacular debut novel opens in a jail cell in Mumbai, where Ram Mohammad Thomas is being held after correctly answering all Vikas Swarup twelve questions on India’s biggest quiz show, Who Will Win a Billion? It is hard to believe that a poor orphan who has never read a newspaper or gone to school could win such a contest. But through a series of exhila- rating tales Ram explains to his lawyer how episodes in his life gave him the answer to each question. Ram takes us on an amazing review of his own history—from the day he was found as a baby in the clothes donation box of a Delhi church to his employment by a faded Bollywood star to his adven- ture with a security-crazed Australian army colonel, to his career as an overly creative tour guide at the Taj Mahal. In his warm-hearted tale lies all the comedy, tragedy, joy and pathos of modern India. Vikas Vikas Swarup is an Indian diplomat who has served in Turkey, the United Swarup States, Ethiopia, and Great Britain. This novel, his first, was originally published as Q&A; it has now been popularized as Slumdog Millionaire by Danny Boyle’s award-winning film. Swarup’s second novel is Six Suspects. Christopher Simpson’s first major role was in the BBC miniseries White Teeth, based on the novel by Zadie Smith. He has also appeared in the films Brick Lane, Shameless, All About George, and State of Play. He has made many recordings for BBC Radio. -

S. No TITLE AUTHOR 1 the GREAT INDIAN MIDDLE CLASS PAVAN K

JAWAHARLAL NEHRU INDIAN CULTURAL CENTRE EMBASSY OF INDIA JAKARTA JNICC JAKARTA LIBRARY BOOK LIST (PDF version) LARGEST COLLECTION OF INDIAN WRITINGS IN INDONESIA Simple way to find your favourite book ~ write the name of the Book / Author of your choice in “FIND” ~ Note it down & get it collected from the Library in charge of JNICC against your Library membership card. S. No TITLE AUTHOR 1 1 THE GREAT INDIAN MIDDLE CLASS PAVAN K. VERMA 2 THE GREAT INDIAN MIDDLE CLASS PAVAN K. VERMA 3 SOCIAL FORESTRY PLANTATIONS K.M. TIWARI & R.V. SINGH 4 INDIA'S CULTURE. THE STATE, THE ARTS AND BEYOND. B.P. SINGH 5 INDIA'S CULTURE. THE STATE, THE ARTS AND BEYOND. B.P. SINGH 6 INDIA'S CULTURE. THE STATE, THE ARTS AND BEYOND. B.P. SINGH UMA SHANKAR JHA & PREMLATA 7 INDIAN WOMEN TODAY VOL. 1 PUJARI 8 INDIA AND WORLD CULTURE V. K. GOKAK VIDYA NIVAS MISHRA AND RFAEL 9 FROM THE GANGES TO THE MEDITERRANEAN ARGULLOL 10 DISTRICT DIARY JASWANT SINGH 11 TIRANGA OUR NATIONAL - FLAG LT. Cdr.K. V. SINGH (Retd) 12 PAK PROXY WAR. A STORY OF ISI, BIN LADEN AND KARGIL RAJEEV SHARMA 13 THE RINGING RADIANCE SIR COLIN GARBETT S. BHATT & AKHTAR MAJEED 14 ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT AND FEDERALISM (EDITOR) 15 KAUTILYA TODAY JAIRAM RAMESH VASUDHA DALMIA, ANGELIKA 16 CHARISMA & CANON MALINAR, MARTIN CHRISTOF (EDITOR) 17 A GOAN POTPOURRI ANIBAL DA COSTA 18 SOURCES OF INDIAN TRADITION VOL. 2 STEPHEN HAY (EDITOR) 19 SECURING INDIA'S FUTURE IN THE NEW MILLENNIUM BRAHMA CHELLANEY(EDITOR) 20 INDIA FROM MIDNIGHT TO THE MILLENNIUM SHASHI THAROOR 21 DOA (BHS INDONESIA) M. -

Film Adaptation of Vikas Swarup's Q&A

Pramana Research Journal ISSN NO: 2249-2976 India’s Real Fiction Meets World’s Popular Cinema - Film Adaptation of Vikas Swarup's Q&A Sreenivas Andoju Dept. of English, Chaitanya Bharathi Institute of Technology Hyderabad, India Dr. Suneetha Yadav Dept. of English, Rajiv Gandhi Memorial College of Engineering & Technology, Nandyal, Kurnool, India Abstract The Indian Foreign Services (IFS) official Vikas Swarup penned “Q & A”, a work of fiction that portrayed the ground realities of Dharavi, a slum in Mumbai. A few years later Danny Boyle adapted the book and created an improbable yet scintillating success making it the best British film of that decade which portrayed Dharavi’s rooftops in the most cinematic technique possible. In this context, this research paper attempts to explore and analyse critically, the purpose and the socio-political connotations such adaptation reverberated by an all new portrayal of Indian story on the celluloid both for the local and global audiences. Amitabh Bachchan commented on Slumdog Millionaire that "if the film projects India as Third World's dirty underbelly developing nation and causes pain and disgust among nationalists and patriots, let it be known that a murky underbelly exists and thrives even in the most developed nations." “(Times of India & The Guardian, 2009) So, what could be the hidden purpose behind such portrayal by Danny Boyle and How were the Indian reactions spoken or otherwise and why? are a few issues that are intended to explore and present in this paper. Keywords: Popularity, Reality, Fiction, Adaptation. Introduction A work of fiction be it a novel or a film is boundary less but when it is viewed from social or political perspectives, there needs a critical debate and clarity. -

PKK Attack’ Kills Two Police Well As Individual NATO Allies, the European Union and the UN.— AP Al-Qaeda Attacks As Tensions Boil in Turkey US-Trained Rebels

INTERNATIONAL SATURDAY, AUGUST 1, 2015 Two of four Indians held in Libya released NEW DELHI: Two Indian teachers who Moamer Kadhafi-in the jihadist group’s first were detained in an area of Libya that the such military gain in Libya. They have since Islamic State group claims to control have claimed to control the whole of the city. been released but two of their colleagues Ministry spokesman Vikas Swarup said the are still being held, the New Delhi govern- Indian mission in Tripoli “came to know that ment said yesterday. four Indian nationals who were returning to India’s foreign ministry said it was able India, via Tripoli and Tunis, were detained at to “secure the release” of the two after the a checkpoint” around 11 pm Thursday. group was detained at a checkpoint around “We are in regular touch with the fami- 30 miles Sirte late Thursday and taken to lies concerned and all efforts are being the southern coastal city. The teachers, who made to ensure (their) well-being and ear- had been working at Sirte university, were ly release,” Swarup told journalists earlier heading for Tripoli where they intended to yesterday in New Delhi. Indian media catch a flight out of the country. “I am hap- reported that the IS group may be holding py we have been able to secure the release the teachers. A senior ministry official said of Lakshmikant and Vijay Kumar. Trying for no individual or group had yet tried to (the) other two,” Foreign Minister Sushma make contact or issue a ransom demand. -

Amongst Friends: the Australian Cult Film Experience Renee Michelle Middlemost University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2013 Amongst friends: the Australian cult film experience Renee Michelle Middlemost University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Middlemost, Renee Michelle, Amongst friends: the Australian cult film experience, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Social Sciences, Media and Communication, University of Wollongong, 2013. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/4063 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Amongst Friends: The Australian Cult Film Experience A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY From UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG By Renee Michelle MIDDLEMOST (B Arts (Honours) School of Social Sciences, Media and Communications Faculty of Law, Humanities and The Arts 2013 1 Certification I, Renee Michelle Middlemost, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of Social Sciences, Media and Communications, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Renee Middlemost December 2013 2 Table of Contents Title 1 Certification 2 Table of Contents 3 List of Special Names or Abbreviations 6 Abstract 7 Acknowledgements 8 Introduction -

Big Synergy and Phantom Films Enter Into an Alliance to Create a Content Production Powerhouse Across Tv and Digital Media

BIG SYNERGY AND PHANTOM FILMS ENTER INTO AN ALLIANCE TO CREATE A CONTENT PRODUCTION POWERHOUSE ACROSS TV AND DIGITAL MEDIA Mumbai, 1st July , 2016: Big Synergy Media and Phantom Films have forged an alliance to create a content production powerhouse, to deliver relevant and impactful entertainment content across TV and Digital Media. With the new alliance, both Big Synergy and Phantoms Films will benefit from each other’s core expertise to expand their businesses. Big Synergy will now have access to the tremendous creative talent resource of Phantom Films to expand their offering into the fiction segment for both TV and Digital Media. Phantom Films will build on Big Synergy’s well-established leadership in factual entertainment to expand their business in the TV and Digital Media. Phantom Films will also now have access to Big Synergy’s expertise and reach in production of regional language content across seven languages in the fiction & non-fiction space. BIG Synergy, promoted by Siddhartha Basu and Anita Kaul Basu, has built its reputation as a leader in the field of factual entertainment, starting off as one of the country's first independent television production houses in 1988. Big Synergy has since then been at the helm of producing some of the country’s most critically acclaimed and popular television programmes. Keeping abreast of constantly changing viewership and growth of regional markets, Big Synergy has incorporated top of the line technology and state-of the art techniques, creating content and programme ideas in sync with market demands across India. Phantom Films, established in 2011 by four prolific filmmakers , Anurag Kashyap, Vikas Bahl ,Vikramaditya Motwane and Madhu Mantena has earned a reputation for producing some of India’s most path breaking and engaging films in recent times. -

Slumdog Millionaire: the Film, the Reception, the Book, the Global

Wright State University CORE Scholar English Language and Literatures Faculty Publications English Language and Literatures 2012 Slumdog Millionaire: The Film, the Reception, the Book, the Global Alpana Sharma Wright State University - Main Campus, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/english Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Repository Citation Sharma, A. (2012). Slumdog Millionaire: The Film, the Reception, the Book, the Global. Literature/Film Quarterly, 40 (3), 197-215. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/english/230 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English Language and Literatures at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Language and Literatures Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. S1mtido5 l11Dlio11~: ~lte FD11:1., -Cite ~ecop"Cio11., -Cite Book., -Cite 61obel1 Danny Boyle's S/11n1dog Millionaire was the runaway commercial hit of 2009 in the United States, nominated for ten Oscars and bagging eight of these, including Best Picture and Best Director. Also included in its trophy bag arc seven British Academy Film awards, all four of the Golden Globe awards for which it was nominated, and five Critics' Choice awards. Viewers and critics alike attribute the film's unexpected popularity at the box office to its universal underdog theme: A kid from the slums of Mumbai makes it to the game show ll"ho lfa11ts to Be a Mil/io11aire and wins not only the money but also the girl. -

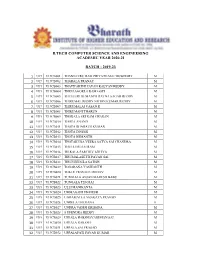

B.Tech Computer Science and Engineering Academic Year 2020-21

B.TECH COMPUTER SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING ACADEMIC YEAR 2020-21 BATCH : 2019-23 1 U19 U19CB001 THANNEERU RAM PRIYATHAM CHOWDARY M 2 U19 U19CB002 THARALA PRANAY M 3 U19 U19CB003 THATIPARTHI PAVAN KALYAN REDDY M 4 U19 U19CB004 THELLAGORLA RAM GOPI M 5 U19 U19CB005 THELLURI HEMANTH RATNA SAGAR REDDY M 6 U19 U19CB006 THIRUMAL REDDY NITHIN KUMAR REDDY M 7 U19 U19CB007 THIRUMALAI VASAN R M 8 U19 U19CB008 THIRUMANI THARUN M 9 U19 U19CB009 THOKALA SRI RAM CHARAN M 10 U19 U19CB010 THOTA ANAND M 11 U19 U19CB011 THOTA BHARATH KUMAR M 12 U19 U19CB012 THOTA DINESH M 13 U19 U19CB013 THOTA HEMANTH M 14 U19 U19CB014 THOTAKURA VEERA SATYA SAI CHANDRA M 15 U19 U19CB015 THULLURI SAI RAM M 16 U19 U19CB016 TIKKALA PARTHIV ADITYA M 17 U19 U19CB017 TIRUMALASETTI PAVAN SAI M 18 U19 U19CB018 TIRUVEEDULA SATISH M 19 U19 U19CB019 TOGARANA YASWANTH M 20 U19 U19CB020 TOKLE PRASAD UDDHAV M 21 U19 U19CB021 TUMMALA ANJAN MAHESH BABU M 22 U19 U19CB022 TUNGALA TEJOSAI M 23 U19 U19CB023 ULLI MANIKANTA M 24 U19 U19CB024 UMMAGANI VIGNESH M 25 U19 U19CB025 UNDAMATLA VENKATA PRASAD M 26 U19 U19CB026 UNDELA LEKHANA F 27 U19 U19CB027 UNDRA VAMSI KRISHNA M 28 U19 U19CB028 S UPENDRA REDDY M 29 U19 U19CB029 UPPALA HARSHAVARDHAN SAI M 30 U19 U19CB030 UPPALA RAKESH M 31 U19 U19CB031 UPPALA SAI PRASAD M 32 U19 U19CB032 UPPALAPATI PAVAN KUMAR M 33 U19 U19CB033 UPPARI SAI RAHUL M 34 U19 U19CB034 UPPU SATHISH M 35 U19 U19CB035 UPPUTURI AKANKSHA F 36 U19 U19CB036 VADDELLI SRIJA F 37 U19 U19CB037 VADDI AKASH M 38 U19 U19CB038 VADLA SAI BHARGAVA ACHARI M 39 U19 U19CB039 VADLA SHRAVAN KUMAR -

1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study People

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study People lives in the world have maintained a goal, which can motivate someone to become survive in the world. Each people have a different maintain a goal, but it has a same purpose to make a better life. Many people lives to make a life better than before. They must work hard and endeavor to get better. They have the same opportunity to get their property, prosperity, and happiness. They can change their destiny and make a life better thing as they wish. The way to change their destiny and to hope their wish is called endeavor for life. According to Meizeir (Meizeir, Email: www.selfgrowth.com.2008) “Struggle is any personal goal achievement accompanied by discomfort and resistance. Struggle may still certainly involve overcoming resistance and discomfort”. Struggle or also called endeavor has a general meaning as a way to get the best result and something worth. People will do everything to get it. This occurs in many kinds of field, one of them in literary works. Literary work which has idea of endeavor elements such as novel, poetry, and movie. Movie has the same position in textual studies. Sometimes it reflex’s a daily life, history, or legends. That the meaning of movie has become part of daily life, which is more complicated than the other works. 1 2 Making a movie is not like writing a novel. It needs a teamwork, which involves many people as crew. Film has many elements, such as director, script, writer, editor, music composer, artistic, costume, designer, etc. -

Darling Telugu Movie Hindi Dubbed Download

Darling Telugu Movie Hindi Dubbed Download 1 / 4 Darling Telugu Movie Hindi Dubbed Download 2 / 4 3 / 4 Darling is a 2010 Indian Telugu-language romantic comedy film directed by A. Karunakaran. ... It was later dubbed in Hindi under the title Sabse Badhkar Hum by Goldmines Telefilms in .... Create a book · Download as PDF · Printable version .... (2010) 720p BrRipx264 Dual audio (Hindi Naayak(2013) Telugu 5 .... /free-download-darling-2010-full-movie-hindi-telugu- dual-audio-300mb/ .. Sabse Badhkar Hum (Darling) 2015 Hindi Dubbed Movie With Telugu Songs | Prabhas - The movie starts in the late 1980s when a group of .... 78f063afee Bollywood 720p Movies; . Home Darling 2016 Hindi-Telugu Movie 850mb Download BluRay Darling-2016-Full-Movie .. hd movies .... 10 Lakh Free Videos for download 1000s of Videos added every day Best Indian app to create and edit videos with filters and stickers in .... Watch Darling Telugu Movie In English Subs Prabhas Movie - Download ur Movies Online. ... 50 Prabhas images download HD for photos wallpaper pics |. More information .... Sketch (2018) 720p HDRip x264 Dual Audio (Hindi DD2.1-Tamil.. The film was declared a flop at the box office and was dubbed in Hindi as 'Meri ... Darling (2010) is an Indian Telugu-language family drama film, directed by A.. Darling movie free download 2010 telugu cinema. ... Sabse badhkar hum darling 2015 hindi dubbed movie with telugu songs prabhas. Darling telugu full movie .... Darling (2010) Telugu BRRip 720p x264 AAC ... Click here to download movie torrent ... The Dirty Picture(2011) - Telugu Dubbed - 1Cd - Dv... Okay Darling Poster · Trailer .... Trending Hindi Movies and Shows .. -

The Rhetoric of Masculinity and Machismo in the Telugu Film Industry

TAMING OF THE SHREW: THE RHETORIC OF MASCULINITY AND MACHISMO IN THE TELUGU FILM INDUSTRY By Vishnupriya Bhandaram Submitted to Central European University Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisors: Vlad Naumescu Dorit Geva CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2015 Abstract Common phrases around the discussion of the Telugu Film Industry are that it is sexist and male-centric. This thesis expounds upon the making and meaning of masculinity in the Telugu Film Industry. This thesis identifies and examines the various intangible mechanisms, processes and ideologies that legitimise gender inequality in the industry. By extending the framework of the inequality regimes in the workplace (Acker 2006), gendered organisation theory (Williams et. al 2012) to an informal and creative industry, this thesis establishes the cyclical perpetuation (Bourdieu 2001) of a gender order. Specifically, this research identifies the various ideologies (such as caste and tradition), habituated audiences, and portrayals of ideal masculinity as part of a feedback loop that abet, reify and reproduce gender inequality. CEU eTD Collection i Acknowledgements “It is not that there is no difference between men and women; it is how much difference that difference makes, and how we choose to frame it.” Siri Hustvedt, The Summer Without Men At the outset, I would like to thank my friends old and new, who patiently listened to my rants, fulminations and insecurities; and for being agreeable towards the unreasonable demands that I made of them in the weeks running up to the completion of this document.