Generic Legislation of New Psychoactive Drugs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Pre-Clinical Studies Have Influenced Novel Psychoactive Substance Legislation in the UK and Europe

Article How preclinical studies have influenced novel psychoactive substance legislation in the UK and Europe Santos, Raquel, Guirguis, Amira and Davidson, Colin Available at http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/31793/ Santos, Raquel ORCID: 0000-0003-3129-6732, Guirguis, Amira and Davidson, Colin ORCID: 0000-0002-8180-7943 (2020) How preclinical studies have influenced novel psychoactive substance legislation in the UK and Europe. British Journal Of Clinical Pharmacology, 86 (3). pp. 452-481. ISSN 0306-5251 It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bcp.14224 For more information about UCLan’s research in this area go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/researchgroups/ and search for <name of research Group>. For information about Research generally at UCLan please go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/research/ All outputs in CLoK are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including Copyright law. Copyright, IPR and Moral Rights for the works on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the policies page. CLoK Central Lancashire online Knowledge www.clok.uclan.ac.uk How Pre-Clinical Studies Have Influenced Novel Psychoactive Substance Legislation in The UK and Europe Raquel Santos1, Amira Guirguis2 & Colin Davidson1* 1School of Pharmacy & Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Clinical & Biomedical Sciences, University of Central Lancashire, UK. 2Swansea University Medical School, Institute of Life Sciences 2, Swansea University, Swansea, Wales, UK. *Corresponding author Colin Davidson School of Pharmacy and Biomedical Science Faculty of Clinical & Biomedical Sciences University of Central Lancashire Preston PR1 2HE +44 (0)1772 89 3920 [email protected] Key words: novel psychoactive substance, legal high, legislation, toxicity, abuse Running Head: review of NPS pharmacology The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare Page | 1 Abstract Novel psychoactive substances (NPS) are new drugs of abuse. -

Zoletil 100 Injectable Anaesthetic/Sedative for Dogs, Cats, Zoo and Wild Animals

Zoletil 100 Injectable Anaesthetic/Sedative for Dogs, Cats, Zoo and Wild Animals Virbac (Australia) Pty Limited Chemwatch Hazard Alert Code: 1 Chemwatch: 6978267 Issue Date: 11/01/2019 Version No: 4.1.16.10 Print Date: 08/31/2021 Safety Data Sheet according to WHS Regulations (Hazardous Chemicals) Amendment 2020 and ADG requirements L.GHS.AUS.EN SECTION 1 Identification of the substance / mixture and of the company / undertaking Product Identifier Product name Zoletil 100 Injectable Anaesthetic/Sedative for Dogs, Cats, Zoo and Wild Animals Chemical Name Not Applicable Synonyms APVMA No.: 38837 Chemical formula Not Applicable Other means of identification Not Available Relevant identified uses of the substance or mixture and uses advised against Relevant identified uses For the anaesthesia and immobilisation of dogs, cats, zoo and wild animals. Details of the supplier of the safety data sheet Registered company name Virbac (Australia) Pty Limited Address 361 Horsley Road Milperra NSW 2214 Australia Telephone 1800 242 100 Fax +61 2 9772 9773 Website au.virbac.com Email [email protected] Emergency telephone number Association / Organisation Poisons Information Centre Emergency telephone 13 11 26 numbers Other emergency telephone Not Available numbers SECTION 2 Hazards identification Classification of the substance or mixture NON-HAZARDOUS CHEMICAL. NON-DANGEROUS GOODS. According to the WHS Regulations and the ADG Code. ChemWatch Hazard Ratings Min Max Flammability 1 Toxicity 1 0 = Minimum Body Contact 1 1 = Low 2 = Moderate Reactivity 1 3 = High Chronic 0 4 = Extreme Poisons Schedule S4 Classification [1] Not Applicable Label elements Hazard pictogram(s) Not Applicable Signal word Not Applicable Hazard statement(s) Not Applicable Precautionary statement(s) Prevention Not Applicable Precautionary statement(s) Response Not Applicable Precautionary statement(s) Storage Page 1 continued.. -

Overview of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971

Psychoactive Substances Bill Factsheet: Overview of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 1. The provisions of the Psychoactive Substances Bill will build on and complement the existing legislative framework for the control of dangerous drugs as contained in the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (the 1971 Act). This factsheet provides an overview of the provisions of the 1971 Act. The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 2. The 1971 Act provides the legislative framework for the regulation of “dangerous or otherwise harmful” drugs; the Act applies to the whole of the United Kingdom. The 1971 Act implements the UK’s international obligations under the United Nations Conventions for the prevention of drug misuse and trafficking, namely the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs 19611 and the Convention on Psychotropic Substances 19712, which are complemented by the Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances 19883. 3. The 1971 Act applies to "controlled drugs". This includes substances or products specified in Schedule 2 to the Act. That Schedule divides controlled drugs into one of three Classes – A, B and C – broadly based on their relative harms, with Class A drugs considered the most harmful. Examples of each class of drug are: Class A - cocaine, methadone and opium; Class B - amphetamine, cannabis and ketamine; Class C - khat and temazepam. In addition, controlled drugs include any substance or product specified in a temporary class drug order as a drug subject to temporary control (see below). 4. The 1971 Act provides for a range of offences in relation to controlled drugs, including: • importation and exportation (section 3); • production, supply or offering to supply (section 4); • possession and possession with intent to supply (section 5); and • permitting premises to be used for certain activities, including the production or supply of a controlled drug and smoking cannabis (section 8). -

Peakal: Protons I Have Known and Loved — Fifty Shades of Grey-Market Spectra

PeakAL: Protons I Have Known and Loved — Fifty shades of grey-market spectra Stephen J. Chapman* and Arabo A. Avanes * Correspondence to: Isomer Design, 4103-210 Victoria St, Toronto, ON, M5B 2R3, Canada. E-mail: [email protected] 1H NMR spectra of 28 alleged psychedelic phenylethanamines from 15 grey-market internet vendors across North America and Europe were acquired and compared. Members from each of the principal phenylethanamine families were analyzed: eleven para- substituted 2,5-dimethoxyphenylethanamines (the 2C and 2C-T series); four para-substituted 3,5-dimethoxyphenylethanamines (mescaline analogues); two β-substituted phenylethanamines; and ten N-substituted phenylethanamines with a 2-methoxybenzyl (NBOMe), 2-hydroxybenzyl (NBOH), or 2,3-methylenedioxybenzyl (NBMD) amine moiety. 1H NMR spectra for some of these compounds have not been previously reported to our knowledge. Others have reported on the composition of “mystery pills,” single-dose formulations obtained from retail shops and websites. We believe this is the first published survey of bulk “research chemicals” marketed and sold as such. Only one analyte was unequivocally misrepresented. This collection of experimentally uniform spectra may help forensic and harm-reduction organizations identify these compounds, some of which appear only sporadically. The complete spectra are provided as supplementary data.[1] Keywords: 1H NMR, drug checking, grey markets, research chemicals, phenylethanamines, N-benzyl phenylethanamines, PiHKAL DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.16889/isomerdesign-1 Published: 1 August 2015 Version: 1.03 “Once you get a serious spectrum collection, Nevertheless, an inherent weakness of grey markets is the the tendency is to push it as far as you can.”1 absence of regulatory oversight. -

Ormond Beach Daytona Beach Holly Hill Your Own

GROW INSIDE ORMOND BEACH DAYTONA BEACH HOLLY HILL YOUR OWN In Garden Nook: Orchids not that hard Page A13 Vol. 6, No. 31 Your Local News and Information Source • www.HometownNewsOL.com Friday, Aug. 26, 2011 Community New state laws mean less You can earn money from home talking about what you already know! If you feel like you Notes are an expert on anything, sign up start earning money as a FREE oversight for local development Broadcaster!and Dance clinic planned • STREAM & SELL YOUR VIDEOS • STREAM AND SELL YOUR LIVE EVENTS By John Bozzo Mr. Goss said this will mean less is what local govern- • VIDEOS ON DEMAND ENCORE Baton & Dance For Hometown News paperwork but more responsibility ments use to regu- studio in Holly Hill will hold Also Offering Videos on Demand for local officials, who are still sort- late land use within Sell your event or educational videos online. a free show and clinic from ORMOND BEACH — With slides ing out what the new law means their cities. They 9:30 a.m. to noon, Saturday, projected on a screen in a small and how decisions in one commu- are used to plan for Aug. 27. No experience is room, the City Commission recent- nity will impact a neighboring the needs of the SIGN UP FOR FREE! necessary. ly studied what responsibilities a community. communities and WWW.HDBroadcasters.COM For more information new state law on growth and urban While many believe the relax- to protect natural about this free clinic, call planning will place in their hands. -

Patient Risks & Preparation for a Successful Sedation Or Anesthetic Event

Patient risks & Sleep preparation for a successful well… sedation or anesthetic event Odette O, DVM, DACVAA ▪ Sedation versus general anesthetic: what are the considerations? ▪ What are the risks (literally) of sedation &/or anesthesia? ▪ Optimize patient preparation prior to sedation/anesthesia whenever possible! ▪ Be prepared: Who? What? Where? When? Why? ▪ Troubleshooting a rough recovery… ▪ ↑ risk of mortality seen with increasing ASA status ▪ Importance of patient evaluation and stabilization PRIOR to commencement of procedure ▪ Identify risk factors and monitor carefully ▪ Largest proportion of deaths in post-procedure period ▪ Continued patient monitoring & support vital • Diagnostic Imaging • Radiographs, CT, U/S • Biopsies • Small wound repair • Bandaging • Convenience • Faster recovery times • Reversible options • ↓ $ • ↑ margin of safety ▪ Reversible unconsciousness ▪ Amnesia ▪ Analgesia ▪ Muscle relaxation ▪ Perform a procedure ▪ w/o suffering ▪ Safety ▪ Patient ▪ Veterinary Care Provider(s) ▪ Multi-modal approach ▪ DO NOT “mask down” (canine/feline) patients! ▪ Patient & occupational safety concerns ▪ MAC (minimum alveolar concentration) = amount of inhalant needed for 50% of patients non- responsive to supramaximal stimulus ▪ Isoflurane: ≈ 1.3% canine, ≈1.6% feline ▪ Sevoflurane: ≈ 2.3% canine, ≈ 3% feline ▪ allows estimate of amount inhalant required ▪ factors: procedure, patient pre-med response, inhalant ▪ Minimal calculations needed ▪ Inhalant effective in every species we encounter ▪ Predictable effects on most patients, -

Download Book Sacred Journeys As

Sa cred Jour neys: ©2015, 2016, 2017 Artscience Im ages: authors and friends, com pany and press pic- tures, PhotoDisc, Corel, Wikipedia, Mindlift Beeldbankiers. Dis tri bu tion: Boekencoöperatie Nederland u.a. email: [email protected] www.boekcoop.nl www.boekenroute.nl (webshop) All rights re served, in clud ing dig i tal re dis tri bu tion and ebook First editiion: De cem ber 2015, Sec ond, ap pended edition April 2016 Third edition Jan. 2017 ISBN 9789492079091 pub lisher: Onderstroomboven Collectief im print: Artscience. Pa perback price € 6,95 Con tents 1 Pre fa ce 7 2 Tripping: the process 10 Journey to the dream 10 The pre pa ra ti on 11 Pha ses, gig gling 13 Iso la ti on, li mi na li ty, the dark 14 Peak 19 Sit ters: de sig na ted hel pers 22 The mys ti cal, re gres si on 26 Rebirth and de ath 27 The end of the trip: co ming down 28 Over sti mu la ti on 29 The af ter-ef fects 30 3 Set and Set ting 32 Agen da 33 Pla ce 34 With whom, with what? 34 Bon ding and trans fe ren ce 35 Dif fe rent ways of using 36 4 Pur po se 37 Dee per goals 38 Over co ming fear 40 To le ran ce 41 5 Ri tu als and Group ses sions 42 He a ling jour neys, mys ti cal in sights 44 Me di cal use 45 Re pe ti ti on, loops 46 Stages of a ritu al 49 Ri tes of pas sa ge: ini ti a ti on 50 Contact – alignment - group mind 52 Struc tu re amidst cha os 54 To copy an existing ritu al or to crea te somet hing new 54 6 Sanc tu a ry, safe spa ce 57 Sa fe ty first 57 Sa cred spa ce, tem po ra ry au to no mous zone 58 Hol ding spa ce and cir cle in te gri ty 61 7 His to ry -

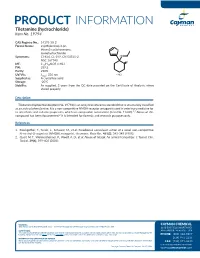

Download Product Insert (PDF)

PRODUCT INFORMATION Tiletamine (hydrochloride) Item No. 19794 CAS Registry No.: 14176-50-2 Formal Name: 2-(ethylamino)-2-(2- thienyl)-cyclohexanone, S monohydrochloride Synonyms: CI-634, CL-399, CN 54521-2, HN NSC 167740 O MF: C12H17NOS • HCl FW: 259.8 Purity: ≥98% • HCl UV/Vis.: λmax: 236 nm Supplied as: A crystalline solid Storage: -20°C Stability: As supplied, 2 years from the QC date provided on the Certificate of Analysis, when stored properly Description Tiletamine (hydrochloride) (Item No. 19794) is an analytical reference standard that is structurally classified as an arylcyclohexylamine. It is a non-competitive NMDA receptor antagonist used in veterinary medicine for its anesthetic and sedative properties, which are comparable to ketamine (Item No. 11630).1,2 Abuse of this compound has been documented.2 It is intended for forensic and research purposes only. References 1. Klockgether, T., Turski, L., Schwarz, M., et al. Paradoxical convulsant action of a novel non-competitive N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist, tiletamine. Brain Res. 461(2), 343-348 (1988). 2. Quail, M. T., Weimersheimer, P., Woolf, A. D., et al. Abuse of telazol: An animal tranquilizer. J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 39(4), 399-402 (2001). WARNING CAYMAN CHEMICAL THIS PRODUCT IS FOR RESEARCH ONLY - NOT FOR HUMAN OR VETERINARY DIAGNOSTIC OR THERAPEUTIC USE. 1180 EAST ELLSWORTH RD SAFETY DATA ANN ARBOR, MI 48108 · USA This material should be considered hazardous until further information becomes available. Do not ingest, inhale, get in eyes, on skin, or on clothing. Wash thoroughly after handling. Before use, the user must review the complete Safety Data Sheet, which has been sent via email to your institution. -

Temporary Class Drug Order Report: 5-6APB and Nbome Compounds

ACMD Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs Chair: Professor Les Iversen Secretary: Rachel Fowler 3rd Floor (SW), Seacole Building 2 Marsham Street London SW1P 4DF Tel: 020 7035 0555 [email protected] Home Secretary Rt Hon. Theresa May MP Home Office 2 Marsham Street London SW1P 4DF 29 May 2013 Dear Home Secretary, I am writing to formally request that you consider laying a temporary class drug order (TCDO) pursuant to section 2A of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 on the following two groups of novel psychoactive substances (NPS). We consider the laying of TCDOs is appropriate as a pre-emptive measure in advance of the summer music festival season. Both classes of drugs have been associated with serious harm and drug-related deaths. ‘Benzofury’ compounds 5- and 6-APB and related substances are phenethylamine-type materials, related to ecstasy (MDMA). There have been several deaths and hospitalisations in the UK associated with these NPS, although poly-substance use often complicates the case. Research indicates that there is a potential risk of cardiac toxicity associated with the long-term use of 5- and 6-APB. Anecdotal user reports suggest that the consumption of these substances can cause insomnia, increased heart rate and anxiety, with some users reporting MDMA like symptoms. The related compound 5-IT has been subject to an EMCDDA-Europol joint report and an EMCDDA risk assessment exercise. [www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/joint-reports/5- IT] 1 The substances recommended for control are: 5- and 6-APB: (1-(benzofuran-5-yl)-propan-2-amine and 1-(benzofuran-6-yl)-propan- 2-amine) and their N-methyl derivatives. -

The Role of the N-Methyl-D-Aspartate Receptors in Social Behavior in Rodents

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review The Role of the N-Methyl-D-Aspartate Receptors in Social Behavior in Rodents Iulia Zoicas * and Johannes Kornhuber Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University Hospital, Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nuremberg, 91054 Erlangen, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-9131-85-46005; Fax: +49-9131-85-36381 Received: 8 October 2019; Accepted: 5 November 2019; Published: 9 November 2019 Abstract: The appropriate display of social behaviors is essential for the well-being, reproductive success and survival of an individual. Deficits in social behavior are associated with impaired N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-mediated neurotransmission. In this review, we describe recent studies using genetically modified mice and pharmacological approaches which link the impaired functioning of the NMDA receptors, especially of the receptor subunits GluN1, GluN2A and GluN2B, to abnormal social behavior. This abnormal social behavior is expressed as impaired social interaction and communication, deficits in social memory, deficits in sexual and maternal behavior, as well as abnormal or heightened aggression. We also describe the positive effects of pharmacological stimulation of the NMDA receptors on these social deficits. Indeed, pharmacological stimulation of the glycine-binding site either by direct stimulation or by elevating the synaptic glycine levels represents a promising strategy for the normalization of genetically-induced, pharmacologically-induced or innate deficits in social behavior. We emphasize on the importance of future studies investigating the role of subunit-selective NMDA receptor ligands on different types of social behavior to provide a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms, which might support the development of selective tools for the optimized treatment of disorders associated with social deficits. -

Anesthetic and Physiologic Effects of Tiletamine, Zolazepam, Ketamine, and Xylazine Combination (TKX) in Feral Cats Undergoing Surgical Sterilization

Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery (2004) 6, 297e303 www.elsevier.com/locate/jfms Anesthetic and physiologic effects of tiletamine, zolazepam, ketamine, and xylazine combination (TKX) in feral cats undergoing surgical sterilization Alexis M. Cistolaa, Francis J. Golderb, Lisa A. Centonzea, ) Lindsay W. McKaya, Julie K. Levya, aDepartment of Small Animal Clinical Sciences, PO Box 100126, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32610, USA bDepartment of Comparative Bioscience, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, USA Revised 23 November 2003; accepted 26 November 2003 Summary Tiletamine (12.5 mg), zolazepam (12.5 mg), ketamine (20 mg), and xylazine (5mg)(TKX;0.25ml,IM)combinationwasevaluatedasananestheticin22maleand67 female adult feral cats undergoing sterilization at high-volume sterilization clinics. Cats were not intubated and breathed room air. Oxygen saturation (SpO2), mean blood pres- sure (MBP), heart rate (HR), respiration rate (RR), and core body temperature were re- corded. Yohimbine (0.25 ml, 0.5 mg, IV) was administered at the completion of surgery. TKXproducedrapidonsetoflateralrecumbency(4G1 min) and surgical anesthesia of sufficient duration to complete surgical procedures in 92% of cats. SpO2 measured via a lingual pulse oximeter probe averaged 92G3% in male cats and 90G4% in females. SpO2 fell below 90% at least once in most cats. MBPmeasuredbyoscillometryaveraged 136G30 mm Hg in males and 113G29 mm Hg in females. MBP increased at the onset of surgical stimulation suggesting incomplete anti-nociceptive properties. HR averaged 156G19bpm,andRRaveraged18G8 bpm. Neither parameter varied between males and females or over time. Body temperature decreased significantly over time, declining to 38.0G0.8 (C at the time of reversal in males and 36.6G0.8 (Catthetimeofreversal in females. -

21 CFR Ch. II (4–1–10 Edition) § 1308.12

§ 1308.12 21 CFR Ch. II (4–1–10 Edition) Some trade and other names: N,N- whenever the existence of such salts, Diethyltryptamine; DET isomers, and salts of isomers is possible (18) Dimethyltryptamine ................................................. 7435 Some trade or other names: DMT within the specific chemical designa- (19) 5-methoxy-N,N-diisopropyltryptamine (other tion: name: 5-MeO-DIPT) ................................................... 7439 (1) gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (some other names in- (20) Ibogaine .................................................................. 7260 clude GHB; gamma-hydroxybutyrate; 4- Some trade and other names: 7-Ethyl- hydroxybutyrate; 4-hydroxybutanoic acid; sodium 6,6b,7,8,9,10,12,13-octahydro-2-methoxy-6,9- oxybate; sodium oxybutyrate) .................................... 2010 methano-5H-pyrido [1′, 2′:1,2] azepino [5,4-b] (2) Mecloqualone ........................................................... 2572 indole; Tabernanthe iboga (3) Methaqualone ........................................................... 2565 (21) Lysergic acid diethylamide ..................................... 7315 (22) Marihuana .............................................................. 7360 (f) Stimulants. Unless specifically ex- (23) Mescaline ............................................................... 7381 cepted or unless listed in another (24) Parahexyl—7374; some trade or other names: 3- schedule, any material, compound, Hexyl-1-hydroxy-7,8,9,10-tetrahydro-6,6,9-trimethyl- 6H-dibenzo[b,d]pyran; Synhexyl. mixture,