Galactic Mapping with General Relativity and the Observed Rotation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April Constellations of the Month

April Constellations of the Month Leo Small Scope Objects: Name R.A. Decl. Details M65! A large, bright Sa/Sb spiral galaxy. 7.8 x 1.6 arc minutes, magnitude 10.2. Very 11hr 18.9m +13° 05’ (NGC 3623) high surface brighness showing good detail in medium sized ‘scopes. M66! Another bright Sb galaxy, only 21 arc minutes from M65. Slightly brighter at mag. 11hr 20.2m +12° 59’ (NGC 3627) 9.7, measuring 8.0 x 2.5 arc minutes. M95 An easy SBb barred spiral, 4 x 3 arc minutes in size. Magnitude 10.5, with 10hr 44.0m +11° 42’ a bright central core. The bar and outer ring of material will require larger (NGC 3351) aperature and dark skies. M96 Another bright Sb spiral, about 42 arc minutes east of M95, but larger and 10hr 46.8m +11° 49’ (NGC 3368) brighter. 6 x 4 arc minutes, magnitude 10.1. Located about 48 arc minutes NNE of M96. This small elliptical galaxy measures M105 only 2 x 2.1 arc minutes, but at mag. 10.3 has very high surface brightness. 10hr 47.8m +12° 35’ (NGC 3379) Look for NGC 3384! (110NGC) and NGC 3389 (mag 11.0 and 12.2) which form a small triangle with M105. NGC 3384! 10hr 48.3m +12° 38’ See comment for M105. The brightest galaxy in Leo, this Sb/Sc spiral galaxy shines at mag. 9.5. Look for NGC 2903!! 09hr 32.2m +21° 30’ a hazy patch 11 x 4.7 arc minutes in size 1.5° south of l Leonis. -

The Skyscraper 2009 04.Indd

A Better Galaxy Guide: Early Spring M67: One of the most ancient open clusters known and Craig Cortis is a great novelty in this regard. Located 1.7° due W of mag NGC 2419: 3.25° SE of mag 6.2 66 Aurigae. Hard to find 4.3 Alpha Cancri. and see; at E end of short row of two mag 7.5 stars. Highly NGC 2775: Located 3.7° ENE of mag 3.1 Zeta Hydrae. significant and worth the effort —may be approximately (Look for “Head of Hydra” first.) 300,000 light years distant and qualify as an extragalactic NGC 2903: Easily found at 1.5° due S of mag 4.3 Lambda cluster. Named the Intergalactic Wanderer. Leonis. NGC 2683: Marks NW “crook” of coathanger-type triangle M95: One of three bright galaxies forming a compact with easy double star mag 4.2 Iota Cancri (which is SSW by triangle, along with M96 and M105. All three can be seen 4.8°) and mag 3.1 Alpha Lyncis (at 6° to the ENE). together in a low power, wide field view. M105 is at the NE tip of triangle, midway between stars 52 and 53 Leonis, mag Object Type R.A. Dec. Mag. Size 5.5 and 5.3 respectively —M95 is at W tip. Lynx NGC 3521: Located 0.5° due E of mag 6.0 62 Leonis. M65: One of a pair of bright galaxies that can be seen in NGC 2419 GC 07h 38.1m +38° 53’ 10.3 4.2’ a wide field view along with M66, which lies just E. -

ALABAMA University Libraries

THE UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA University Libraries Hot Diffuse Emission in the Nuclear Starburst Region of NGC 2903 Jimmy A. Irwin – University of Alabama et al. Deposited 09/12/2018 Citation of published version: Yukita, M., et al. (2012): Hot Diffuse Emission in the Nuclear Starburst Region of NGC 2903. The Astrophysical Journal, 758(2). http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0004-637X/758/2/105 © 2012. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. The Astrophysical Journal, 758:105 (17pp), 2012 October 20 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/758/2/105 C 2012. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. HOT DIFFUSE EMISSION IN THE NUCLEAR STARBURST REGION OF NGC 2903 Mihoko Yukita1, Douglas A. Swartz2, Allyn F. Tennant3, Roberto Soria4, and Jimmy A. Irwin1 1 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL 35487, USA 2 Universities Space Research Association, NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, ZP12, Huntsville, AL 35812, USA 3 Space Science Office, NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, ZP12, Huntsville, AL 35812, USA 4 International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research, Curtin University, GPO Box U1987, Perth, WA 6845, Australia Received 2012 June 14; accepted 2012 August 30; published 2012 October 5 ABSTRACT We present a deep Chandra observation of the central regions of the late-type barred spiral galaxy NGC 2903. The Chandra data reveal soft (kTe ∼ 0.2–0.5 keV) diffuse emission in the nuclear starburst region and extending ∼2 (∼5 kpc) to the north and west of the nucleus. Much of this soft hot gas is likely to be from local active star-forming regions; however, besides the nuclear region, the morphology of hot gas does not strongly correlate with the bar or other known sites of active star formation. -

SAC's 110 Best of the NGC

SAC's 110 Best of the NGC by Paul Dickson Version: 1.4 | March 26, 1997 Copyright °c 1996, by Paul Dickson. All rights reserved If you purchased this book from Paul Dickson directly, please ignore this form. I already have most of this information. Why Should You Register This Book? Please register your copy of this book. I have done two book, SAC's 110 Best of the NGC and the Messier Logbook. In the works for late 1997 is a four volume set for the Herschel 400. q I am a beginner and I bought this book to get start with deep-sky observing. q I am an intermediate observer. I bought this book to observe these objects again. q I am an advance observer. I bought this book to add to my collect and/or re-observe these objects again. The book I'm registering is: q SAC's 110 Best of the NGC q Messier Logbook q I would like to purchase a copy of Herschel 400 book when it becomes available. Club Name: __________________________________________ Your Name: __________________________________________ Address: ____________________________________________ City: __________________ State: ____ Zip Code: _________ Mail this to: or E-mail it to: Paul Dickson 7714 N 36th Ave [email protected] Phoenix, AZ 85051-6401 After Observing the Messier Catalog, Try this Observing List: SAC's 110 Best of the NGC [email protected] http://www.seds.org/pub/info/newsletters/sacnews/html/sac.110.best.ngc.html SAC's 110 Best of the NGC is an observing list of some of the best objects after those in the Messier Catalog. -

![Arxiv:2011.04984V1 [Astro-Ph.GA]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3147/arxiv-2011-04984v1-astro-ph-ga-1213147.webp)

Arxiv:2011.04984V1 [Astro-Ph.GA]

Received: 00 Month 0000 Revised: 00 Month 0000 Accepted: 00 Month 0000 DOI: xxx/xxxx ORIGINAL PAPER New dwarfs around the curly spiral galaxy M 63 I.D. Karachentsev1 | F. Neyer, R. Späni, T. Zilch2 1Russian Academy of Sciences, Special Astrophysical Observatory, N.Arkhyz, KChR, Russia We present a deep (50 hours exposed) image of the nearby spiral galaxy M63 2Fachgruppe Astrofotografie, Tief Belichtete (NGC5055), taken with a 0.14-m aperture telescope. The galaxy halo exhibits the Galaxien group of Vereinigung der Sternfreunde e.V., PO Box 1169, D-64629, known very faint system of stellar streams extending across 110 kpc. We found 5 Heppenheim, Germany very low-surface-brightness dwarf galaxies around M63. Assuming they are satel- Correspondence lites of M63, their median parameters are: absolute B-magnitude –8.8 mag, linear *Russian Academy of Sciences, Special diameter 1.3 kpc, surface brightness ∼ 27.8 mag/sq. arcsec and linear projected sep- Astrophysical Observatory, N.Arkhyz, aration 93 kpc. Based on four brighter satellites with measured radial velocities, we KChR, Russia Email: [email protected] 11 derived a low orbital mass estimate of M63 to be (5.1±1.8)10 M⊙ on a scale of Present Address ∼ 216 kpc. The specific property of M63 is its declining rotation curve. Taking into *Russian Academy of Sciences, Special Astrophysical Observatory, N.Arkhyz, account the declining rotation curves of the M63 and three nearby massive galaxies KChR, Russia NGC2683, NGC2903, NGC3521, we recognize their low mean orbital mass-to-K- band luminosity ratio, (4.8±1.1) M⊙∕L⊙, that is only ∼ 1∕6 of the corresponding ratio for the Milky Way and M31. -

00E the Construction of the Universe Symphony

The basic construction of the Universe Symphony. There are 30 asterisms (Suites) in the Universe Symphony. I divided the asterisms into 15 groups. The asterisms in the same group, lay close to each other. Asterisms!! in Constellation!Stars!Objects nearby 01 The W!!!Cassiopeia!!Segin !!!!!!!Ruchbah !!!!!!!Marj !!!!!!!Schedar !!!!!!!Caph !!!!!!!!!Sailboat Cluster !!!!!!!!!Gamma Cassiopeia Nebula !!!!!!!!!NGC 129 !!!!!!!!!M 103 !!!!!!!!!NGC 637 !!!!!!!!!NGC 654 !!!!!!!!!NGC 659 !!!!!!!!!PacMan Nebula !!!!!!!!!Owl Cluster !!!!!!!!!NGC 663 Asterisms!! in Constellation!Stars!!Objects nearby 02 Northern Fly!!Aries!!!41 Arietis !!!!!!!39 Arietis!!! !!!!!!!35 Arietis !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1056 02 Whale’s Head!!Cetus!! ! Menkar !!!!!!!Lambda Ceti! !!!!!!!Mu Ceti !!!!!!!Xi2 Ceti !!!!!!!Kaffalijidhma !!!!!!!!!!IC 302 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 990 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1024 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1026 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1070 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1085 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1107 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1137 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1143 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1144 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1153 Asterisms!! in Constellation Stars!!Objects nearby 03 Hyades!!!Taurus! Aldebaran !!!!!! Theta 2 Tauri !!!!!! Gamma Tauri !!!!!! Delta 1 Tauri !!!!!! Epsilon Tauri !!!!!!!!!Struve’s Lost Nebula !!!!!!!!!Hind’s Variable Nebula !!!!!!!!!IC 374 03 Kids!!!Auriga! Almaaz !!!!!! Hoedus II !!!!!! Hoedus I !!!!!!!!!The Kite Cluster !!!!!!!!!IC 397 03 Pleiades!! ! Taurus! Pleione (Seven Sisters)!! ! ! Atlas !!!!!! Alcyone !!!!!! Merope !!!!!! Electra !!!!!! Celaeno !!!!!! Taygeta !!!!!! Asterope !!!!!! Maia !!!!!!!!!Maia Nebula !!!!!!!!!Merope Nebula !!!!!!!!!Merope -

Galaxy NGC 2903

A&A 411, 41–53 (2003) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20030952 & c ESO 2003 Astrophysics An X-ray halo in the “hot-spot” galaxy NGC 2903 D. Tsch¨oke1, G. Hensler1, and N. Junkes2 1 Institut f¨ur Theoretische Physik und Astrophysik, Universit¨at Kiel, 24098 Kiel, Germany 2 Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Radioastronomie, Auf dem H¨ugel 69, 53121 Bonn, Germany Received 2 February 2001/ Accepted 16 June 2003 Abstract. In this paper we present ROSAT PSPC and HRI observations of the “hot-spot” galaxy NGC 2903. This isolated system strikingly reveals a soft extended X-ray feature reaching in north-west direction up to a projected distance of 5.2 kpc from the center into the halo. The residual X-ray emission in the disk reveals the same extension as the Hα disk. No eastern counterpart of the western X-ray halo emission has been detected. The luminosity of the extraplanar X-ray gas is several 1038 erg s−1, comparable to X-ray halos in other starburst galaxies. It has a plasma temperature of about 0.2 keV. The estimated −1 star formation rate derived from X-rays and Hα results in 1–2 M yr . Since galactic superwinds, giant kpc-scale galactic outflows, seem to be a common phenomenon observed in a number of edge-on galaxies, especially in the X-ray regime, and are produced by excess star-formation activity, the existence of hot halo gas as found in NGC 2903 can be attributed to events such as central starbursts. That such a starburst has taken place in NGC 2903 must be proven. -

Photometric Distances to Six Bright Resolved Galaxies?

ASTRONOMY & ASTROPHYSICS MARCH II 2000, PAGE 425 SUPPLEMENT SERIES Astron. Astrophys. Suppl. Ser. 142, 425–432 (2000) Photometric distances to six bright resolved galaxies? I.O. Drozdovsky1 and I.D. Karachentsev2 1 Astronomical Institute, St.-Petersburg State University, Petrodvoretz 198904, Russia 2 Special Astrophysical Observatory, N. Arkhyz, KChR 357147, Russia Received September 27; accepted October 18, 1999 Abstract. We present photometry of the brightest stars in et al. 1994; Georgiev et al. 1997; Makarova et al. 1997; six nearby spiral and irregular galaxies with corrected ra- Karachentsev et al. 1997; Makarova & Karachentsev dial velocities from 340 to 460 km s−1. Three of them are 1998; Karachentsev & Drozdovsky 1998; Tikhonov & resolved into stars for the first time. Based on luminosity Karachentsev 1998). Besides several early type objects of the brightest blue stars we estimate the following dis- (NGC 404, NGC 4150, NGC 4736, NGC 4826, and Maffei tances to the galaxies: 5.0 Mpc for NGC 784, 9.2 Mpc for 1) all of the galaxies are resolved into stars, moreover NGC 2683, 8.9 Mpc for NGC 2903, 4.1 Mpc for NGC 5204, most of them for the first time. 6.8 Mpc for NGC 5474, and 8.7 Mpc for NGC 5585. Here we present large-scale images of three previously unobserved galaxies: NGC 784, NGC 2683, NGC 2903, Key words: galaxies: distances — galaxies: general as well as of three galaxies, NGC 5204, NGC 5474, and NGC 5585, from the M 101 group imaged with a higher angular resolution. 1. Introduction 2. Observations and photometry This paper completes a series of publications devoted The first four galaxies were observed in February 1995 to photometry of the brightest stars in nearby late type at the 2.5-m Nordic telescope with a subarcsec seeing. -

AYOSH Demo Chapter

DEMO CHAPTER Winter - January We start the year of Star Hopping at its beginning, in chilly January. By this point, I was 14 episodes into the Star Hopping series on YouTube, which was started in September. So that’s why we’re starting with Episode 14. We’ll roll over to Episode 1, nine months from now; in September. The months of Winter give rise to the brightest stars in the sky, anchored in the constellations of Orion, Canis Major, Canis Minor, and Gemini. In the northern climes, the weather may be frigid, but on those cold, clear nights, the stars shine more steadily, as the cold dry air makes for spectacular “seeing”. Chapter 4 - Leo We’ll be looking into the constellation of Leo for our Star Hopping targets in this chapter. I’ll be keeping you up a little later to around 11:30 PM, to see Leo the Lion appearing up over the eastern horizon. Even though we’re in January, we are A YEAR OF STAR HOPPING DAVID HEARN PAGE !1 OF !7 DEMO CHAPTER starting to get hints of the constellations of Spring starting to appear late in the evenings. This begins the time to see galaxies! The constellation of Leo portrays the great Lion, with the head of the lion appearing as a very recognizable backwards question mark, and the tail shaped like a large triangle. Leo rises with the head of the lion facing straight up, and within it’s borders lie many deep sky objects, most of which are as I mentioned, galaxies. -

New Constraints on the $^{12} $ CO (2-1)/(1-0) Line Ratio Across

MNRAS 000,1–23 (2018) Preprint 22 March 2021 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 New Constraints on the 12CO¹2 − 1º/¹1 − 0º Line Ratio Across Nearby Disc Galaxies J. S. den Brok,1 D. Chatzigiannakis,1 F. Bigiel,1 J. Puschnig,1 A. T. Barnes,1 A. K. Leroy,2 M. J. Jiménez-Donaire,3 A. Usero,3 E. Schinnerer,4 E. Rosolowsky,5 C. M. Faesi,6 K. Grasha,7 A. Hughes,8 J. M. D. Kruijssen,9 D. Liu,4 L. Neumann,1 J. Pety,10,11 M. Querejeta,3 T. Saito,4 A. Schruba,12 S. Stuber4 1 Argelander-Institut für Astronomie, Universität Bonn, Auf dem Hügel 71, 53121 Bonn, Germany 2Department of Astronomy, The Ohio State University, 4055 McPherson Laboratory, 140 West 18th Avenue, Columbus, OH 43210, USA 3Observatorio Astronómico Nacional (IGN), C/Alfonso XII 3, E-28014 Madrid, Spain 4Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Königstuhl 17, D-69117 Heidelberg, Germany 54-183 CCIS, University of Alberta, Edmonton AB T6G 2E1, Alberta, Canada 6Dept. of Astronomy, University of Massachusetts - Amherst, 710 N. Pleasant Street, Amherst, MA 01003, USA 7Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2611, Australia 8Université de Toulouse, UPS-OMP, F-31028 Toulouse, France ; CNRS, IRAP, Av. du Colonel Roche BP 44346, F-31028 Toulouse cedex 4, France 9Astronomisches Rechen-Institut, Zentrum für Astronomie der Universität Heidelberg, Mönchhofstraße 12-14, 69120 Heidelberg 10IRAM, 300 rue de la Piscine, F-38406 Saint Martin d’Hères, France 11Sorbonne Université, Observatoire de Paris, Université PSL, École normale supérieure, CNRS, LERMA, F-75005, Paris, France 12Max-Planck Institut für Extraterrestrische Physik, Giessenbachstraße 1, 85748 Garching, Germany Accepted 2021 March 12. -

A VLT Study of Metal-Rich Extragalactic H II Regions

A&A 441, 981–997 (2005) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20053369 & c ESO 2005 Astrophysics A VLT study of metal-rich extragalactic H II regions I. Observations and empirical abundances, F. Bresolin1, D. Schaerer2,3, R. M. González Delgado4, and G. Stasinska´ 5 1 Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu 96822, USA e-mail: [email protected] 2 Observatoire de Genève, 51 Ch. des Maillettes, 1290 Sauverny, Switzerland e-mail: [email protected] 3 Laboratoire Astrophysique de Toulouse-Tarbes (UMR 5572), Observatoire Midi-Pyrénées, 14 avenue E. Belin, 31400 Toulouse, France 4 Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía (CSIC), Apdo. 3004, 18080 Granada, Spain e-mail: [email protected] 5 LUTH, Observatoire de Paris-Meudon, 5 place Jules Jansen, 92195 Meudon, France e-mail: [email protected] Received 5 May 2005 / Accepted 3 June 2005 ABSTRACT We have obtained spectroscopic observations from 3600 Å to 9200 Å with FORS at the Very Large Telescope for approximately 70 H regions located in the spiral galaxies NGC 1232, NGC 1365, NGC 2903, NGC 2997 and NGC 5236. These data are part of a project to measure the chemical abundances and characterize the massive stellar content of metal-rich extragalactic H regions. In this paper we describe our dataset, and present emission line fluxes for the whole sample. In 32 H regions we measure at least one of the following auroral lines: [S ] λ4072, [N ] λ5755, [S ] λ6312 and [O ] λ7325. From these we derive electron temperatures, as well as oxygen, nitrogen and sulphur abundances, using classical empirical methods (both so-called “Te-based methods” and “strong line methods”). -

P10263v1.2 Lab 9 Text

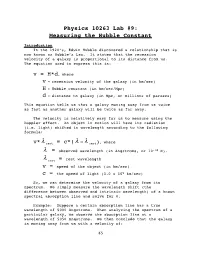

Physics 10263 Lab #9: Measuring the Hubble Constant Introduction In the 1920’s, Edwin Hubble discovered a relationship that is now known as Hubble’s Law. It states that the recession velocity of a galaxy is proportional to its distance from us. The equation used to express this is: v = H*d, where v = recession velocity of the galaxy (in km/sec) H = Hubble constant (in km/sec/Mpc) d = distance to galaxy (in Mpc, or millions of parsecs) This equation tells us that a galaxy moving away from us twice as fast as another galaxy will be twice as far away. The velocity is relatively easy for us to measure using the Doppler effect. An object in motion will have its radiation (i.e. light) shifted in wavelength according to the following formula: v* λ rest = c*( λ - λ rest), where λ = observed wavelength (in Angstroms, or 10-10 m). λ rest = rest wavelength v = speed of the object (in km/sec) c = the speed of light (3.0 x 105 km/sec) So, we can determine the velocity of a galaxy from its spectrum. We simply measure the wavelength shift (the difference between observed and intrinsic wavelength) of a known spectral absorption line and solve for v. Example: Suppose a certain absorption line has a true wavelength of 5000 Angstroms. When analyzing the spectrum of a particular galaxy, we observe the absorption line at a wavelength of 5050 Angstroms. We then conclude that the galaxy is moving away from us with a velocity of: !65 (5050-5000) v = [ /5000] * 300,000 = 3000 km/sec In order to estimate the distances to galaxies, we’re going to use a distance determination technique known as the “standard ruler”.