Price Daniel, Texas Democrats, and School Segregation, 1956-1957

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chiafalo-Reply-20-04-30 FINAL

No. 19-465 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States PETER BRET CHIAFALO, LEVI JENNET GUERRA, AND ESTHER VIRGINIA JOHN, Petitioners, v. STATE OF WASHINGTON, Respondent. On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Washington REPLY BRIEF FOR PRESIDENTIAL ELECTORS L. LAWRENCE LESSIG Counsel of Record JASON HARROW EQUAL CITIZENS 12 Eliot Street Cambridge, MA 02138 (617) 496-1124 [email protected] (additional counsel on inside cover) SUMEER SINGLA JONAH O. HARRISON DANIEL A. BROWN ARETE LAW GROUP PLLC HUNTER M. ABELL 1218 Third Ave. WILLIAMS KASTNER & Suite 2100 GIBBS, PLLC Seattle, WA 98101 601 Union St. (206) 428-3250 Suite 4100 Seattle, WA 98101 (206) 628-6600 DAVID H. FRY J. MAX ROSEN MUNGER, TOLLES & OLSON LLP 560 Mission St., 27th Floor San Francisco, CA 94105 (415) 512-4000 i TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................... i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................... ii INTRODUCTION ......................................................... 1 I. The Framers Explicitly Rejected Any Direct Mode For Choosing The President, And Chose Instead An Indirect Method That Requires Elector Discretion. ............................................. 3 II. Recognizing A Constitutional Discretion In Electors Is Compelled By Ray v. Blair. ............ 7 III. Washington Has Identified No Power To Authorize Its Regulation Of The “Federal Function In Balloting.” .................................... 13 IV. A Political Pledge Has Never Been Legally Enforceable. ...................................................... 17 V. There Is A Continuing Need For Elector Discretion Within Our System For Electing The President. .................................................. 20 CONCLUSION ........................................................... 23 ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES PAGE(S) FEDERAL CASES Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission, 135 S. Ct. 2652 (2015) ..................... 13 Bogan v. Scott-Harris, 523 U.S. -

Resolutions to Censure the President: Procedure and History

Resolutions to Censure the President: Procedure and History Updated February 1, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45087 Resolutions to Censure the President: Procedure and History Summary Censure is a reprimand adopted by one or both chambers of Congress against a Member of Congress, President, federal judge, or other government official. While Member censure is a disciplinary measure that is sanctioned by the Constitution (Article 1, Section 5), non-Member censure is not. Rather, it is a formal expression or “sense of” one or both houses of Congress. Censure resolutions targeting non-Members have utilized a range of statements to highlight conduct deemed by the resolutions’ sponsors to be inappropriate or unauthorized. Before the Nixon Administration, such resolutions included variations of the words or phrases unconstitutional, usurpation, reproof, and abuse of power. Beginning in 1972, the most clearly “censorious” resolutions have contained the word censure in the text. Resolutions attempting to censure the President are usually simple resolutions. These resolutions are not privileged for consideration in the House or Senate. They are, instead, considered under the regular parliamentary mechanisms used to process “sense of” legislation. Since 1800, Members of the House and Senate have introduced resolutions of censure against at least 12 sitting Presidents. Two additional Presidents received criticism via alternative means (a House committee report and an amendment to a resolution). The clearest instance of a successful presidential censure is Andrew Jackson. The Senate approved a resolution of censure in 1834. On three other occasions, critical resolutions were adopted, but their final language, as amended, obscured the original intention to censure the President. -

Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135Th Anniversary

107th Congress, 2d Session Document No. 13 Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135th Anniversary 1867–2002 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2002 ‘‘The legislative control of the purse is the central pil- lar—the central pillar—upon which the constitutional temple of checks and balances and separation of powers rests, and if that pillar is shaken, the temple will fall. It is...central to the fundamental liberty of the Amer- ican people.’’ Senator Robert C. Byrd, Chairman Senate Appropriations Committee United States Senate Committee on Appropriations ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia, TED STEVENS, Alaska, Ranking Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ANIEL NOUYE Hawaii D K. I , ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania RNEST OLLINGS South Carolina E F. H , PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ATRICK EAHY Vermont P J. L , CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri OM ARKIN Iowa T H , MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky ARBARA IKULSKI Maryland B A. M , CONRAD BURNS, Montana ARRY EID Nevada H R , RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama ERB OHL Wisconsin H K , JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire ATTY URRAY Washington P M , ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah YRON ORGAN North Dakota B L. D , BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado IANNE EINSTEIN California D F , LARRY CRAIG, Idaho ICHARD URBIN Illinois R J. D , KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas IM OHNSON South Dakota T J , MIKE DEWINE, Ohio MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JACK REED, Rhode Island TERRENCE E. SAUVAIN, Staff Director CHARLES KIEFFER, Deputy Staff Director STEVEN J. CORTESE, Minority Staff Director V Subcommittee Membership, One Hundred Seventh Congress Senator Byrd, as chairman of the Committee, and Senator Stevens, as ranking minority member of the Committee, are ex officio members of all subcommit- tees of which they are not regular members. -

Warren Commission, Volume XXII: CE 1364

'Yarborougla..,.Invited - i By CARL FREUND The developments came afterltive plans callJFfor Drmocratic ~I`6'Tra *A'With 13 ; President Kennedy has invited Yarborough's supporters charged !-gressmen to fly into Dallas ~Sen . Ralph Yarborough to fly into that Gov . John Connally and con-!Love Field with President Ken- ',Dallas aboard the presidential jet ,servaave leaders were trying tolnedy and Vice-President Johnson . ~airiiner Friday, The Dallas News force the liberal senator to "take They will arrive at 11 :30 a .m . learned Tuesday. amt travel in a motorcade through ~ Rued on Kennedy ~Downtowrt Dallas, arriving at the Meanwhile, the three groups visit, Pages 4,4 , S and 6 . the nonpartisan lunch- -Trade Mart on Stemmons Free- 'toneon for the President an ,ounced!a back seat" durml, hr. K+nnedy ;wayat 12 :30P.m . ;they have invited Yarborough to l visit to Texas. Plans call for Reps. Ray Rob '. sit at the head table . I An informed source said tents_jerts, Olin Teague and Litdley (Beckworth to ride in the jet wilt; DALLAS SPEECH President and Mrs. Kennedy and ISen. Yarborough. Reps. Jack t?rnaks, Albert Thomas, Homer Thornherry, Jim U.S. Stronger, Wealthier 'Wright, Graham Purcell, John Young. George Mahon . Walter 'Rogers, Henry Gonzalez and Than Ever, Says Johnson IWright Patman were assigned to i fly LEWIS HARRIS He was addressing the conven-I Here he beat the drums for the , VicePresident Johnson's plane . 'I Vice-President Lyndon B . John-1Ion of American Bottlers of Car- .administration's proposed tax cut . In other developments : tson, in a hurried prelude to theibonated Beverages at -,,-at He asserted that the $II^000: ~ -Weather Bureau -rkers, who HaII . -

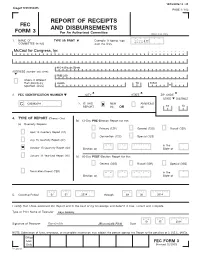

Report of Receipts and Disbursements

10/15/2014 12 : 23 Image# 14978252435 PAGE 1 / 162 REPORT OF RECEIPTS FEC AND DISBURSEMENTS FORM 3 For An Authorized Committee Office Use Only 1. NAME OF TYPE OR PRINT Example: If typing, type 12FE4M5 COMMITTEE (in full) over the lines. McCaul for Congress, Inc 815-A Brazos Street ADDRESS (number and street) PMB 230 Check if different than previously Austin TX 78701 reported. (ACC) 2. FEC IDENTIFICATION NUMBER CITY STATE ZIP CODE STATE DISTRICT C C00392688 3. IS THIS NEW AMENDED REPORT (N) OR (A) TX 10 4. TYPE OF REPORT (Choose One) (b) 12-Day PRE -Election Report for the: (a) Quarterly Reports: Primary (12P) General (12G) Runoff (12R) April 15 Quarterly Report (Q1) Convention (12C) Special (12S) July 15 Quarterly Report (Q2) M M / D D / Y Y Y Y in the October 15 Quarterly Report (Q3) Election on State of January 31 Year-End Report (YE) (c) 30-Day POST -Election Report for the: General (30G) Runoff (30R) Special (30S) Termination Report (TER) M M / D D / Y Y Y Y in the Election on State of M M / D D / Y Y Y Y M M / D D / Y Y Y Y 5. Covering Period 07 01 2014 through 09 30 2014 I certify that I have examined this Report and to the best of my knowledge and belief it is true, correct and complete. Type or Print Name of Treasurer Kaye Goolsby M M / D D / Y Y Y Y 10 15 2014 Signature of Treasurer Kaye Goolsby [Electronically Filed] Date NOTE: Submission of false, erroneous, or incomplete information may subject the person signing this Report to the penalties of 2 U.S.C. -

Onnally Talks of Jfk's Trip

repeatedly to arrange a Texas visit for Kennedy from early 1; 62 on, but that lie delayed it f r personal reasons. He said the Kennedy adminis- ttation was unpopular in Texas SEC.-PION ONE—PAGE TWEI al the time. 1;:.I was desperately trying to play for my own campaign and tO, rally support, and the last ONNALLY TALKS Wrig I wanted was a national allempt for support or political OF JFK'S TRIP money," Connally said. ;However, Connally said he fi- r/ply agreed to the 1963 visit be- Went to Dallas for Own ci1use he knew "if I couldn't ral- Purposes, View ly:support for my own party's Piesident in my own state, it vitould be a political embarrass- NEW YORK (AP) — Gov. dent that I would not be al- John Connally of Texas says kfted to forget." President John F. Kennedy WANTED TO TALK went to Dallas four years ago 'Connally said he dissuaded for his own political purposes— Kennedy from his original plan not to patch up a feud between Lyndon B. Johnson and Sen. Ralph Yarborough. "President Kennedy wanted to visit Texas with two distinct purposes in mind," Connally skid in an article in the current Life magazine. "The first was four fund-raising dinners in to raise funds. The second was 'or Iouston, San Antonio, Fort to improve his own political po- sition in a state that promised to Worth and Dallas, telling him it would look like "you are trying tie critical in the election of 1$64." to financially rape the state." 'Connally, who was wounded He said Kennedy told him when Kennedy was assassinated that, besides fund-raising, he in a Dallas motorcade Nov. -

Of Judicial Independence Tara L

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 71 | Issue 2 Article 3 2018 The Origins (and Fragility) of Judicial Independence Tara L. Grove Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Tara L. Grove, The Origins (and Fragility) of Judicial Independence, 71 Vanderbilt Law Review 465 (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol71/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Origins (and Fragility) of Judicial Independence Tara Leigh Grove* The federal judiciary today takes certain things for granted. Political actors will not attempt to remove Article II judges outside the impeachment process; they will not obstruct federal court orders; and they will not tinker with the Supreme Court's size in order to pack it with like-minded Justices. And yet a closer look reveals that these "self- evident truths" of judicial independence are neither self-evident nor necessary implications of our constitutional text, structure, and history. This Article demonstrates that many government officials once viewed these court-curbing measures as not only constitutionally permissible but also desirable (and politically viable) methods of "checking" the judiciary. The Article tells the story of how political actors came to treat each measure as "out of bounds" and thus built what the Article calls "conventions of judicial independence." But implicit in this story is a cautionary tale about the fragility of judicial independence. -

George I. Sanchez and the Civil Rights Movement: 1940-1960

George I. Sanchez and the Civil Rights Movement: 1940-1960 Ricardo Romo* This article is a tribute to Dr. George I. Sanchez and examines the important contributions he made in establishing the American Council of Spanish-Speaking People (ACSSP) in 1951. The ACSSP funded dozens of civil rights cases in the Southwest during the early 1950's and repre- sented the first large-scale effort by Mexican Americans to establish a national civil rights organization. As such, ACSSP was a precursor of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) and other organizations concerned with protecting the legal rights of Mexican Americans in the Southwest. The period covered here extends from 1940 to 1960, two crucial decades when Mexican Ameri- cans made a concerted effort to challenge segregation in public schools, discrimination in housing and employment, and the denial of equal ac- cess to public places such as theaters, restaurants, and barber shops. Although Mexican Americans are still confronted today by de facto seg- regation and job discrimination, it is of historical and legal interest that Mexican American legal victories, in areas such as school desegregation, predated by many years the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education and the civil rights movement of the 1960's. Sanchez' pioneering leadership and the activities of ACSSP merit exami- nation if we are to fully comprehend the historical struggle of the Mexi- can American civil rights movement. In a recent article, Karen O'Conner and Lee Epstein traced the ori- gins of MALDEF to the 1960's civil rights era.' The authors argued that "Chicanos early on recongized their inability to seek rights through traditional political avenues and thus sporadically resorted to litigation .. -

Report: Tough Choices Facing Florida's Governments

TOUGH CHOICES FACING FLORIDA’S GOVERNMENTS PATTERNS OF RESEGREGATION IN FLORIDA’S SCHOOLS SEPTEMBER 2017 Tough Choices Facing Florida’s Governments PATTERNS OF RESEGREGATION IN FLORIDA’S SCHOOLS By Gary Orfield and Jongyeon Ee September 27, 2017 A Report for the LeRoy Collins Institute, Florida State University Patterns of Resegregation in Florida’s Schools 1 Tough Choices Facing Florida’s Governments TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ..............................................................................................................................................................3 List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................................3 Patterns of Resegregation in Florida’s Schools .........................................................................................................4 The Context of Florida’s School Segregation.............................................................................................................5 Three Supreme Court Decisions Negatively Affecting Desegregation .......................................................................6 Florida Since the 1990s .............................................................................................................................................7 Overview of Trends in Resegregation of Florida’s Schools ........................................................................................7 Public School Enrollment Trend -

Supplement 1

*^b THE BOOK OF THE STATES .\ • I January, 1949 "'Sto >c THE COUNCIL OF STATE'GOVERNMENTS CHICAGO • ••• • • ••'. •" • • • • • 1 ••• • • I* »• - • • . * • ^ • • • • • • 1 ( • 1* #* t 4 •• -• ', 1 • .1 :.• . -.' . • - •>»»'• • H- • f' ' • • • • J -•» J COPYRIGHT, 1949, BY THE COUNCIL OF STATE GOVERNMENTS jk •J . • ) • • • PBir/Tfili i;? THE'UNIfTED STATES OF AMERICA S\ A ' •• • FOREWORD 'he Book of the States, of which this volume is a supplement, is designed rto provide an authoritative source of information on-^state activities, administrations, legislatures, services, problems, and progressi It also reports on work done by the Council of State Governments, the cpm- missions on interstate cooperation, and other agencies concepned with intergovernmental problems. The present suppkinent to the 1948-1949 edition brings up to date, on the basis of information receivjed.from the states by the end of Novem ber, 1948^, the* names of the principal elective administrative officers of the states and of the members of their legislatures. Necessarily, most of the lists of legislators are unofficial, final certification hot having been possible so soon after the election of November 2. In some cases post election contests were pending;. However, every effort for accuracy has been made by state officials who provided the lists aiid by the CouncJLl_ of State Governments. » A second 1949. supplement, to be issued in July, will list appointive administrative officers in all the states, and also their elective officers and legislators, with any revisions of the. present rosters that may be required. ^ Thus the basic, biennial ^oo/t q/7^? States and its two supplements offer comprehensive information on the work of state governments, and current, convenient directories of the men and women who constitute those governments, both in their administrative organizations and in their legislatures. -

The Rules of the Texas Democratic Party to the Extent Permitted by the Texas Election Code:A

The Rules of the Texas 2019- Democratic 2020 Party adopted June 8, 2019 State Democratic Executive Committee 1106 Lavaca • Austin, TX 78701 P.O. Box 116 • Austin, TX 78767 512-478-9800 www.txdemocrats.org Paid for by the Texas Democratic Party • www.txdemocrats.org • This communication not authorized by any candidate or candidate’s committee. Table of Contents RULES OF THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY OF TEXAS I. STATEMENT OF PRINCIPLES . 1 A. Beliefs . 1 B. Declarations . 1 II. NAME, MEMBERSHIP AND OFFICERS . 2 A. Name . 2 B. Membership . 2 C. Party Officers . 2 III. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEES . 2 A. Duties of Executive Committees . 2 B. General Rules . 3 C. Election Matters . 3 1. Certification of Candidates 2. Referendum Issues D. State Democratic Executive Committee . 4 1. Officers 2. SDEC Members 3. Removal 4. Advisory Committee E. County Executive Committee . 6 1. Members 2. Officers 3. Qualifications 4. Election Procedure 5. Vacancies 6. Duties and Responsibilities 7. Meetings 8. Expenditure of Funds 9. County Executive Committee Quorum 10. Meeting of the County Executive Committee F. District Executive Committee . 10 1. Members 2. Officers 3. Duties 4. Other “District Committees” 5. Meetings G. Precinct Executive Committee for the Purpose of Filling a Commissioner or Justice or Constable Precinct Candidate Vacancy . 10 H. Removal From Office for Endorsing Opposing Party or Candidate . 11 I. Duties of District Committees in Special Elections . 11 IV. PARTY CONVENTIONS . 12 A. General Rules Governing Party Conventions . 12 1. Compliance with Rules 2. Publicizing Meetings 3. Rules 4. Voting 5. Media 6. Minority Reports 7. Resolutions 8. Rules 9. -

Texas Department of Corrections: 30 Years of Progress

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. ____~____ ~:-:'----;-- - ~-- ----;--;:-'l~. - Texas Department of Corrections: 30 Years of Progress ,. In 1967, the Department published a report, Texas Department of Corrections: 20 Years of Progress. That report was largely the work of Mr. Richard C. Jones, former Assistant Director for Treatment. The report that follows borrowed hea-vily and in many cases directly from Mr. Jones' efforts. This is but another example of how we continue to profit from, and, hopefully, build upon the excellent wC';-h of those preceding us. Texas Department of Corrections: 30 Years of Progress NCJRS dAN 061978 ACQUISIT10i~:.j OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR DOLPH BRISCOE STATE CAPITOL GOVERNOR AUSTIN, TEXAS 78711 My Fellow Texans: All Texans owe a debt of gratitude to the Honorable H. H. Coffield. former Chairman of the Texas Board of Corrections, who recently retired after many years of dedicated service on the Board; to the present members of the Board; to Mr. W. J. Estelle, Jr., Director of the Texas Department of Corrections; and to the many people who work with him in the management of the Department. Continuing progress has been the benchmark of the Texas Department of Corrections over the past thirty years. Proposed reforms have come to fruition through the careful and diligent management p~ovided by successive administ~ations. The indust~ial and educational p~ograms that have been initiated have resulted in a substantial tax savings for the citizens of this state and one of the lowest recidivism rates in the nation.