Riparian Ecosystems in Mexico: Current Status and Future Direction 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cypress Weevil, Eudociminus Mannerheimii (Boheman) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae)1 Albert E

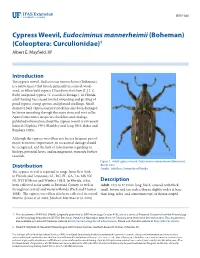

EENY-360 Cypress Weevil, Eudociminus mannerheimii (Boheman) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae)1 Albert E. Mayfield, III2 Introduction The cypress weevil, Eudociminus mannerheimii (Boheman), is a native insect that breeds primarily in scarred, weak- ened, or fallen bald cypress (Taxodium distichum [L.] L.C. Rich) and pond cypress (T. ascendens Brongn.). In Florida, adult feeding has caused limited wounding and girdling of pond cypress stump sprouts and planted seedlings. Small diameter bald cypress nursery stock has also been damaged by larvae tunneling through the main stem and root collar. Apart from entries in species checklists and catalogs, published information about the cypress weevil is extremely limited (Hopkins 1904, Blatchley and Leng 1916, Baker and Bambara 1999). Although the cypress weevil has not been a frequent pest of major economic importance, its occasional damage should be recognized, and the lack of information regarding its biology, potential hosts, and management, warrants further research. Figure 1. Adult cypress weevil, Eudociminus mannerheimii (Boheman), dorsal view. Distribution Credits: Lyle Buss, University of Florida The cypress weevil is reported to range from New York to Florida and Louisiana (AL, DC, FL, GA, LA, MS, NC, NJ, NY) (O’Brien and Wimber 1982). In Florida, it has Description been collected as far south as Broward County, as well as Adult: 10.5 to 17.0 mm long; black, covered with thick, throughout central and western Florida (Peck and Thomas small, brown and tan scales; thorax slightly wider at base 1998). The cypress weevil has also been collected in central than long; sides (and sometimes top) of thorax striped Mexico (Jones et al. -

Diversifying Tree Choices for a Shadier Future

Diversifying Tree Choices for a Shadier Future Adam Black Director, Peckerwood Garden Hempstead TX With special cameo appearance by Dr. David Creech Dr. David Creech Who is this guy? • Former horticulturist at Kanapaha Botanial Gardens, Gainesville FL • Managed Forest Pathology and Forest Entomology labs at University of Florida • Former co-owner of Xenoflora LLC (rare plant mail- order nursery) • Current Director of Peckerwood Garden, Hempstead, Texas Tree Diversity in Landscapes Advantages of diverse tree assemblages • Include many plant families attracts biodiversity (pollinators, predators, etc) that all together reduce pest problems • Diversity means loss is minimal if a new disease targets a particular genus. • Generate excitement and improve aesthetics • Use of locally adapted forms over mainstream selections from distant locations • Adaptations for specific conditions (salt, alkalinity, etc) • If mass plantings are necessary, use seed grown plants for genetic diversity rather than clonally propagated selections Disadvantages of diverse tree assmeblages • Hard to find among the standard issue trees available locally • Hard to convince nurseries to try something new • Initial trialing of new material, many failures among the winners • A disadvantage in some cases – non-native counterparts may be superior to natives. Diseases: • Dutch Elm Disease (Ulmus americana) • Emerald Ash Borer (Fraxinus spp.) • Laurel Wilt (Persea, Sassafras, Lindera, etc) • Crepe Myrtle Bark Scale (Lagerstroemia spp.) • Next? Quercus virginiana Quercus fusiformis Quercus fusiformis Weeping form Quercus virginiana ‘Grandview Gold’ Quercus nigra Variegated Quercus tarahumara Quercus crassifolia Quercus sp. San Carlos Mtns Quercus tarahumara Quercus laeta Quercus polymorpha Quercus germana There is one in the auction! Quercus rysophylla Quercus sinuata var. sinuata Quercus imbricaria (southern forms) Quercus glauca Quercus acutus Quercus schottkyana Quercus marlipoensis Lithocarpus edulis ‘Starburst’ Lithocarpus henryi Lithocarpus kawakamii Platanus rzedowski incorrectly offered as P. -

Evaluation of Selected Provenances of Taxodium Distichum For

EVALUATION OF SELECTED PROVENANCES OF TAXODIUM DISTICHUM FOR DROUGHT, ALKALINITY AND SALINITY TOLERANCE A Dissertation by GEOFFREY CARLILE DENNY Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Major Subject: Horticulture EVALUATION OF SELECTED PROVENANCES OF TAXODIUM DISTICHUM FOR DROUGHT, ALKALINITY AND SALINITY TOLERANCE A Dissertation by GEOFFREY CARLILE DENNY Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Michael A. Arnold Committee Members, Leonardo Lombardini Wayne A. Mackay W. Todd Watson Head of Department, Tim D. Davis May 2007 Major Subject: Horticulture iii ABSTRACT Evaluation of Selected Provenances of Taxodium distichum for Drought, Alkalinity and Salinity Tolerance. (May 2007) Geoffrey Carlile Denny, B.S., Texas A&M University; M.A., The University of Texas Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Michael A. Arnold Taxodium distichum (L.) Rich. is a widely adaptable, long-lived tree species for landscape use. It is tolerant of substantial soil salt levels, but tends to defoliate in periods of extended or severe drought, when leaves come into contact with salty irrigation water, and tends to develop chlorosis on high pH soils. The purpose of this research was to identify provenances which may yield genotypes tolerant of these stresses. The appropriate name for baldcypress is Taxodium distichum (L.) Rich. var. distichum, for pondcypress is T. distichum var. imbricarium (Nutt.) Croom, and for Montezuma cypress is T. distichum var. -

Fables and Foibles of the Coexistence Approach

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/016378; this version posted March 10, 2015. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Grimm et al.; Fables and Foibles of the Coexistence Approach Fables and foibles: a critical analysis of the Palaeoflora database and the Coexistence approach for palaeoclimate reconstruction Guido W. Grimm1,*, Johannes M. Bouchal1,2, Thomas Denk2, Alastair J. Potts3 1 University of Vienna, Department of Palaeontology, Wien; [email protected] 2 Swedish Museum of Natural History, Department of Palaeobiology, Stockholm 3 Nelson-Mandela Metropolitan University, Botany Department, Port Elizabeth * Corresponding author 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/016378; this version posted March 10, 2015. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Grimm et al.; Fables and Foibles of the Coexistence Approach Abstract The “Coexistence Approach” is a mutual climate range (MCR) technique combined with the nearest-living relative (NLR) concept. It has been widely used for palaeoclimate reconstructions based on Eurasian plant fossil assemblages, most of them palynofloras (studied using light microscopy). The results have been surprisingly uniform, typically converging to subtropical, per-humid or monsoonal conditions. Studies based on the coexistence approach have had a marked impact in literature, generating over 10,000 citations thus far. -

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Mao et al. 10.1073/pnas.1114319109 SI Text BEAST Analyses. In addition to a BEAST analysis that used uniform Selection of Fossil Taxa and Their Phylogenetic Positions. The in- prior distributions for all calibrations (run 1; 144-taxon dataset, tegration of fossil calibrations is the most critical step in molecular calibrations as in Table S4), we performed eight additional dating (1, 2). We only used the fossil taxa with ovulate cones that analyses to explore factors affecting estimates of divergence could be assigned unambiguously to the extant groups (Table S4). time (Fig. S3). The exact phylogenetic position of fossils used to calibrate the First, to test the effect of calibration point P, which is close to molecular clocks was determined using the total-evidence analy- the root node and is the only functional hard maximum constraint ses (following refs. 3−5). Cordaixylon iowensis was not included in in BEAST runs using uniform priors, we carried out three runs the analyses because its assignment to the crown Acrogymno- with calibrations A through O (Table S4), and calibration P set to spermae already is supported by previous cladistic analyses (also [306.2, 351.7] (run 2), [306.2, 336.5] (run 3), and [306.2, 321.4] using the total-evidence approach) (6). Two data matrices were (run 4). The age estimates obtained in runs 2, 3, and 4 largely compiled. Matrix A comprised Ginkgo biloba, 12 living repre- overlapped with those from run 1 (Fig. S3). Second, we carried out two runs with different subsets of sentatives from each conifer family, and three fossils taxa related fi to Pinaceae and Araucariaceae (16 taxa in total; Fig. -

Propagation of Taxodium Mucronatum from Softwood Cuttings

Propogation of Taxosium mucronatum from Softwood Cuttings Item Type Article Authors St. Hilaire, Rolston Publisher University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Journal Desert Plants Rights Copyright © Arizona Board of Regents. The University of Arizona. Download date 25/09/2021 03:23:49 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/555909 Taxodium St. Hilaire 29 Propagation of Taxodium softwood cuttings could be used to propagate Mexican bald cypress. mucronatum from Terminal softwood cuttings were collected on 16 October Softwood Cuttings 1998 and 1999. Cuttings were selected from the lower branches of an 11-year-old tree at New Mexico State University's Fabian Garcia Science Center in Las Cruces Rolston St. Hilaire1 (lat. 32° 16' 48" N; long. 106° 45' 18" W), from all branches Department of Agronomy and Horticulture, Box of a 2-year-old tree at an arboretum in Los Lunas, New Mexico (lat. 34° 48' 18" N; long. 106° 43' 42" W), and 30003, New Mexico State University, from all branches of a 2-year-old tree in the display Las Cruces, NM 88003 landscape of a nursery in Los Lunas. Plants of T. mucronatum grow rapidly. The 11-year-old tree was 12m Abstract tall (::::50 main branches), and the 2-year-old trees had Mexican bald cypress (Taxodium mucronatum Ten.) is reached 2 m (:::: 15 main branches). This facilitated the propagated from seed, but procedures have not been reported collection of at least 30 terminal cuttings per tree in each of for the propagation of this ornamental tree by stem cuttings. the two years. All trees were irrigated as necessary, but not This study evaluated the use of softwood cuttings to fertilized. -

(12) United States Plant Patent (10) Patent No.: US PP17,767 P3 Zengji Et Al

USOOPP17767P3 (12) United States Plant Patent (10) Patent No.: US PP17,767 P3 Zengji et al. (45) Date of Patent: May 29, 2007 (54) XTAXODIOMERIA PEIZHONGII TREE (56) References Cited NAMED DONGFANGSHAN PUBLICATIONS (50) Latin Name: xTaxodiomera peizhongi Zhang et al. The characteristics and ecological value of Varietal Denomination: Dongfangshan Taxodium mucronatumxCryptomeria, Jul. 2003. Acta Agri culturae Shanghai, vol. 19, No. 3, pp. 56–59.* (75) Inventors: Ye Zengji, Shanghai (CN); Shen * cited by examiner Lieying, Shanghai (CN); Pan Shihua, Shanghai (CN); Zhu Weijie, Shanghai Primary Examiner Kent Bell Assistant Examiner June Hwu (CN); Niu Huijuan, Shanghai (CN) (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm Armstrong Teasdale LLP (73) Assignee: Shanghai Forestry Station, Shanghai (57) ABSTRACT (CN) XTaxodiomeria peizhongii is a distinct and new above (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this ground nontubular propagated cultivar comprising a tall patent is extended or adjusted under 35 semi-indeciduous arbor tree providing a high view. U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. XTaxodiomeria peizhongii is well Suited for afforestation in the city and has many good properties such as fast growth, (21) Appl. No.: 10/941,465 wide adaptability and strong stress resistance. Its main characteristics include: (1) its base of stem is round and (22) Filed: Sep. 15, 2004 regular without buttress roots; (2) its bark cracks into flakes; (3) there are several main crotches five to eight meters above (65) Prior Publication Data ground, and its canopy is nearly elliptic shape; (4) there are US 2006/0059593 P1 Mar. 16, 2006 only male conglobate flower and no female conglobate fruit on the adult tree, and it cannot reproduce with sexual (51) Int. -

Morphology and Morphogenesis of the Seed Cones of the Cupressaceae - Part I Cunninghamioideae, Athrotaxoideae, Taiwanioideae, Sequoioideae, Taxodioideae

1 2 Bull. CCP 3 (3): 117-136. (12.2014) A. Jagel & V.M. Dörken Morphology and morphogenesis of the seed cones of the Cupressaceae - part I Cunninghamioideae, Athrotaxoideae, Taiwanioideae, Sequoioideae, Taxodioideae Summary Seed cone morphology of the basal Cupressaceae (Cunninghamia, Athrotaxis, Taiwania, Metasequoia, Sequoia, Sequoiadendron, Cryptomeria, Glyptostrobus and Taxodium) is presented at pollination time and at maturity. These genera are named here taxodiaceous Cupressaceae (= the former family Taxodiaceae, except for Sciadopitys). Some close relationships exist between genera within the Sequoioideae and Taxodioideae. Seed cones of taxodiaceous Cupressaceae consist of several bract-/seed scale-complexes. The cone scales represent aggregation of both scale types on different levels of connation. Within Cunninghamia and Athrotaxis the bulges growing out of the cone scales represents the distal tip of the seed scale, which has been fused recaulescent with the adaxial part of the bract scale. In Athrotaxis a second bulge, emerging on the distal part of the cone scale, closes the cone. This bulge is part of the bract scale. Related conditions are found in the seed cones of Taiwania and Sequoioideae, but within these taxa bract- and seed scales are completely fused with each other so that vegetative parts of the seed scale are not recognizable. The ovules represent the only visible part of the seed scale. Within taxodiaceous Cupressaceae the number of ovules is increased compared to taxa of other conifer families. It is developed most distinctly within the Sequoioideae, where furthermore more than one row of ovules appears. The rows develop centrifugally and can be interpreted as short-shoots which are completely reduced to the ovules in the sense of ascending accessory shoots. -

TAXODIACEAE.Publishe

Flora of China 4: 54–61. 1999. 1 TAXODIACEAE 杉科 shan ke Fu Liguo (傅立国 Fu Li-kuo)1, Yu Yongfu (于永福)2; Robert R. Mill3 Trees evergreen, semievergreen, or deciduous, monoecious; trunk straight; main branches ± whorled. Leaves spirally arranged or scattered (decussate in Metasequoia), monomorphic, dimorphic, or trimorphic on same tree, lanceolate, subulate, scalelike, or linear. Microsporophylls and cone scales spirally arranged (decussate in Metasequoia). Pollen cones borne in panicles, or solitary or clustered at branch apices, or axillary, small; microsporangia with (2 or)3 or 4(–9) pollen sacs; pollen nonsaccate. Seed cones terminal or borne near apex of previous year’s growth, ripening in 1st year, persistent or late deciduous; cone scales developing after ovules originate in bract axils; bracts and cone scales usually spirally aranged (decussate in Metasequoia), sessile, opening when ripe (falling in Taxodium), semiconnate and free only at apex, or completely united; bracts occasionally rudimentary (in Taiwania); ovules 2–9 per bract axil, erect or pendulous; cone scales of mature cones flattened or shield-shaped, woody or leathery, 2–9-seeded on abaxial side. Seeds flat or triangular, wingless (in Taxodium), narrowly winged all round or on 2 sides, or with a long wing on proximal part. Cotyledons 2–9. 2n = 22*. Nine genera and 12 species: Asia, North America, and (Athrotaxis D. Don) Tasmania; eight genera (one endemic, three introduced) and nine species (one endemic, four introduced) in China. A merger of the Taxodiaceae and Cupressaceae is increasingly supported by both morphological and molecular evidence (see note under Cupressaceae). However, the two groups are kept as separate families here for pragmatic reasons. -

(Taxodioideae), Cupressaceae, an Overview by GC-MS

Article Terpenoids of the Swamp Cypress Subfamily (Taxodioideae), Cupressaceae, an Overview by GC-MS Bernd R. T. Simoneit 1,*, Angelika Otto 2, Daniel R. Oros 3 and Norihisa Kusumoto 4 1 Department of Chemistry, College of Science, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA 2 Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg, Sektion Paläobotanik, D-60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany 3 Consultant, 72 Marina Lakes Drive, Richmond, CA 94804, USA 4 Wood Extractive Laboratory, Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8687, Japan * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-541-737-2081 Academic Editor: Artur M. S. Silva Received: 16 July 2019; Accepted: 29 July 2019; Published: 21 August 2019 Abstract: The resins bled from stems and in seed cones and leaves of Cryptomeria japonica, Glyptostrobus pensilis, Taxodium distichum, and T. mucronatum were characterized to provide an overview of their major natural product compositions. The total solvent extract solutions were analyzed as the free and derivatized products by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry to identify the compounds, which comprised minor mono- and sesquiterpenoids, and dominant di- and triterpenoids, plus aliphatic lipids (e.g., n-nonacosan-10-ol). Ferruginol, 7α-p- cymenylferruginol, and chamaecydin were the major characteristic markers for the Taxodioideae conifer subfamily. The mass spectrometric data can aid polar compound elucidation in environmental, geological, archeological, forensic and pharmaceutical studies. Keywords: Cryptomeria japonica; Glyptostrobus pensilis; Taxodium distichum; Taxodium mucronatum; Cupressaceae; GC-MS overview; terpenoids 1. Introduction Natural products, especially terpenoids or their derivatives, are preserved in the ambient environment or geological record. When extracted and characterized by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) they are used by organic geochemists as tracers for sources, transport and alteration processes of organic matter in any global compartment [1–15]. -

26 Extreme Trees Pub 2020

Publication WSFNR-20-22C April 2020 Extreme Trees: Tallest, Biggest, Oldest Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care / University Hill Fellow University of Georgia Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources Trees have a long relationship with people. They are both utility and amenity. Trees can evoke awe, mysticism, and reverence. Trees represent great public and private values. Trees most noticed and celebrated by people and communities are the one-tenth of one-percent of trees which approach the limits of their maximum size, reach, extent, and age. These singular, historic, culturally significant, and massive extreme trees become symbols and icons of life on Earth, and our role model in environmental stewardship and sustainability. What Is A Tree? Figure 1 is a conglomeration of definitions and concepts about trees from legal and word definitions in North America. For example, 20 percent of all definitions specifically state a tree is a plant. Concentrated in 63% of all descriptors for trees are four terms: plant, woody, single stem, and tall. If broad stem diameter, branching, and perennial growth habit concepts are added, 87% of all the descriptors are represented. At its most basic level, defining a tree is not species based, but is a structural definition. A tree is represented by a type of plant architecture recognizable by non-technical people. The most basic concepts for defining a tree are — a large, tall, woody, perennial plant with a single, unbranched, erect, self-supporting stem holding an elevated and distinct crown of branches, and which is greater than 10 feet in height and greater than 3 inches in diameter. -

Baldcypress (Taxodium Distichum )

Baldcypress (Taxodium distichum) is one of two species in this genus. The other, Taxodium mucronatum is native to Mexico, Guatemala and the southern most part of Texas. The word taxodium is derived from Taxus (yew) and a suffix meaning like, referring to the yewlike leaves. The word distichum means two- ranked, referring to the leaves being in two rows. Other Common Names: Amerikanische zypresse, amerikansk cypress, bald cypress, baldcypress , black cypress, buck cypress, canoe water pine, Chinese swamp cypress, cipres americano, cipres calvo, cipres de pantano, cipres pond, cipresso calvo, cipresso del sud, cipresso delle paludi, cipresso pond, common bald cypress, common-baldcypress, cow cypress, cupresso delle paludi, cypres chauve, cypres de la Louisiane, cypres de Louisiane, cypres pond, cypress, deciduous cypress, gulf cypress, gulf red cypress, knee cypress, Louisiana black cypress, Louisiana cypress, Louisiana red cypress, moeras-cypres, moerascypres, pecky cypress, pond bald cypress, pond baldcypress, pond cypres, pond cypress, red cypress, river cypress, satine faux, shui ts'ung, shui tsung kan, southern cypress, sump-cypress, sumpcypress, Sumpftaxodie, sumpf- zypresse, Sumpfzypresse, sumpfzypresse, swamp cypress, taxodier chauve, tidewater red cypress, upland cypress, virginische sumpfzedar, white cypress, yellow cypress, zweizeilige Sumpfzypresse. Distribution: Baldcypress grows in swampy areas along the Atlantic coast from Delaware to southern Florida, west along the Gulf Coast to southeastern Texas and along the Mississippi river valley to southeastern Illinois. About one-half of the cypress lumber comes from the Southern States and one-fourth from the South Atlantic States. It is not as readily available as it was several decades ago. The Tree: Baldcypress trees can reach heights of 150 feet, with diameters of 12 feet and an age of 2000 years.