Prof. Dr. Srebren Dizdar University of Sarajevo Situation Analysis Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alternative Report HRC Bosnia

Written Information for the Consideration of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Second Periodic Report by the Human Rights Committee (CCPR/C/BIH/2) SEPTEMBER 2012 Submitted by TRIAL (Swiss Association against Impunity) Association of the Concentration Camp-Detainees Bosnia and Herzegovina Association of Detained – Association of Camp-Detainees of Brčko District Bosnia and Herzegovina Association of Families of Killed and Missing Defenders of the Homeland War from Bugojno Municipality Association of Relatives of Missing Persons from Ilijaš Municipality Association of Relatives of Missing Persons from Kalinovik (“Istina-Kalinovik ‘92”) Association of Relatives of Missing Persons of the Sarajevo-Romanija Region Association of Relatives of Missing Persons of the Vogošća Municipality Association Women from Prijedor – Izvor Association of Women-Victims of War Croatian Association of War Prisoners of the Homeland War in Canton of Central Bosnia Croatian Association of Camp-Detainees from the Homeland War in Vareš Prijedor 92 Regional Association of Concentration Camp-Detainees Višegrad Sumejja Gerc Union of Concentration Camp-Detainees of Sarajevo-Romanija Region Vive Žene Tuzla Women’s Section of the Association of Concentration Camp Torture Survivors Canton Sarajevo TRIAL P.O. Box 5116 CH-1211 Geneva 11 Tél/Fax: +41 22 3216110 [email protected] www.trial-ch.org CCP: 17-162954-3 CONTENTS Contents Paragraphs Background 1. Right to Life and Prohibition of Torture and Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment, Remedies and Administration of Justice (Arts. 6, -

World Bank Document

23671 <: *h :? ' November 2001 J SIAED6JMEN PRI ES lNfE OATOF B SNI HER EGOVINA Public Disclosure Authorized INA ANT/ ~* EN4/\ AVB4 /\ TNCIA/ ANTON\/A NT ** T RZNgATN / NT \IAN - 4*N EVANTO Public Disclosure Authorized /.SA E NTON H G N A I \ / \_ *: NtRETVA\ tANTOs/ \ / \ / L / C_l /\\ / \ / \ / 29 K I~E *>tE'\STC+NTzONHx,ERZG/VINA X / \ : I L~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Public Disclosure Authorized / CzNTOSRvJEV F/I\/E COPY Public Disclosure Authorized CANTONS IN THE FEDERATION OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA UNA - SANA CANTON No. 1 POSAVINA CANTON No. 2 TUZLA CANTON No. 3 ZENICA - DOBOJ CANTON No. 4 DRINA CANTON No. 5 CENTRAL BOSNIAN CANTON No. 6 NERETVA CANTON No. 7 WEST HERZEGOVINA CANTON No. 8 SARAJEVO CANTON No. 9 HERZEG BOSNIAN CANTON No.10 Authors: Miralem Porobic, lawyer and Senada Havic Design: Tirada, Sarajevo. Chris Miller Free publication November 2001 SEED. Sarajevo. Bosnia and Herzegovina This study was done with an aim to determine the level of the actual costs, which must have each small and medium business company when start their operations in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It contains the defined costs for the business registration itself, and for construction of a facility where the registered activity will be performed. The data published in this study were collected through the survey conducted in all municipalities in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in July 2001. After summarizing all collected data, it was determined that there are few identical forms and approaches to the same category of the costs that a small and medium size business company can have as a precondition for starting its normal work. -

THE POSAVINA BORDER REGION of CROATIA and BOSNIA-HERZEGOVINA: DEVELOPMENT up to 1918 (With Special Reference to Changes in Ethnic Composition)

THE POSAVINA BORDER REGION OF CROATIA AND BOSNIA-HERZEGOVINA: DEVELOPMENT UP TO 1918 (with special reference to changes in ethnic composition) Ivan CRKVEN^I] Zagreb UDK: 94(497.5-3 Posavina)''15/19'':323.1 Izvorni znanstveni rad Primljeno: 9. 9. 2003. After dealing with the natural features and social importance of the Posavina region in the past, presented is the importance of this region as a unique Croatian ethnic territory during the Mid- dle Ages. With the appearance of the Ottomans and especially at the beginning of the 16th century, great ethnic changes oc- cured, primarily due to the expulsion of Croats and arrival of new ethnic groups, mostly Orthodox Vlachs and later Muslims and ethnic Serbs. With the withdrawal of the Ottomans from the Pannonian basin to the areas south of the Sava River and the Danube, the Sava becomes the dividing line creating in its border areas two socially and politically different environments: the Slavonian Military Frontier on the Slavonian side and the Otto- man military-frontier system of kapitanates on the Bosnian side. Both systems had a special influence on the change of ethnic composition in this region. With the withdrawal of the Ottomans further towards the southeast of Europe and the Austrian occu- pation of Bosnia and Herzegovina the Sava River remains the border along which, especially on the Bosnian side, further changes of ethnic structure occured. Ivan Crkven~i}, Ilo~ka 34, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia. E-mail: [email protected] INTRODUCTION The research subject in this work is the border region Posavi- na between the Republic of Croatia and the Republic Bosnia- 293 -Herzegovina. -

Jelena Mrgić-Radojčić Faculty of Philosophy Belgrade RETHINKING the TERRITORIAL DEVELOPMENT of the MEDIEVAL BOSNIAN STATE* In

ИСТОРИЈСКИ ЧАСОПИС, књ. LI (2004) стр. 43-64 HISTORICAL REVIEW, Vol. LI (2004) pр. 43-64 УДК : 94(497.15) ”04/14” : 929 Jelena Mrgić-Radojčić Faculty of Philosophy Belgrade RETHINKING THE TERRITORIAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE MEDIEVAL BOSNIAN STATE* In many ways, the medieval Bosnian state developed at the cross- roads – between West and East, the Hungarian Kingdom, a predomi- nantly Western European state, and the Serbian Kingdom, under the strong influence of the Byzantine Empire. One may, without any further elaboration, say that Bosnia formed the periphery of both the Byzantine Empire, and Western Europe (first the Frankish and then the Hungarian state). Bosnia was far away from the most important communication line of the Balkans: the valleys of the rivers Morava and Vardar, Via militaris and also those of the rivers Ibar and Sitnica. The axis of the Bosnian state was the valley of the river Bosna, but not of the Drina ill suited for 1 communication with it steep banks and many canyons. * The author wishes to thank Prof. J. Koder, University of Vienna, Prof. S. Ćirković, Prof. M. Blagojević, and Prof. S. Mišić of Belgrade University for their usuful com- ments and corrections of the following text. 1J. Ferluga, Vizantiska uprava u Dalmaciji, (Byzantine Administration in Dalmatia), Beograd 1957; J. Koder, Der Lebensraum der Byzantiner. Historisch-geographischer Abriß ihres Mittelalterlichen Staates im östlichen Mittelmeerraum, Byzantische Geschichtsschreiber 1, Graz-Wien-Köln 1984, 20012, 13-21, passim; S. Ćirković, Bosna i Vizantija (Bosnia and Byzantium), Osam Stotina godina povelje bana Kulina, Sarajevo 1989, 23-35. Even though Bosnia was situated on the »cross-roads«, it is unacceptable to depict it as being “more of a no-man's-land than a meeting ground between the two worlds“, as J.V.A. -

STUDENT CMJ Learning Through the Community Service

44(1):98-101,2003 STUDENT CMJ Learning through the Community Service Goran Ðuzel, Tina Krišto, Marijo Parèina, Vladimir J. Šimunoviæ Mostar University School of Medicine, Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina Aim. To present a model of teaching general practice to medical students as a part of care for refugees in Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Method. With an international support, 33 medical students (from the third study year on) participated in a total of 51 field visits to 4 refugee camps near Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina, over a period of two years. Some students made more than 30 visits. Together with residents in family medicine at the Mostar University Hospital, the students per- formed physical examinations and small interventions, and distributed packs of different pharmaceutical agents to ref- ugees. At the end of the project, participants were surveyed to assess the benefits of the program. Results. Thirty out of 33 participating students responded to the survey. Fourteen students said that “the opportunity to do something, however small, for the people” was the main benefit from the project, whereas 5 thought that meeting “a real patient” early in their medical studies was very beneficial. The students assisted in 1,302 physical examinations, an average of 25± 8 examinations per visit. The most requested physical examination was blood pressure measure- ment (52%), followed by chest auscultation (24%) and psychological counseling (16%). They also helped with a total of 320 minor procedures, an average of 6± 2 per visit. Among the procedures, wound care and dressing were most common (63.4%), followed by nursing care procedures (20%) and minor surgical procedures (suture removal, abscess drainage, and bed sores débridement) in 6.9% of the cases. -

RASPORED I REZULTATI OMLADINSKE LIGE Bih-GRUPA

COMET - Nogometni/Fudbalski savez Bosne i Hercegovine Datum: 20.09.2021. Raspored takmičenja Organizacija: (2) Nogometni savez Federacije BiH Takmičenje: (20962309) Omladinska liga BiH grupa "Jug" JUNIORI 21/22 - 2021/2022 UKUPNO REZULTATA: 210 Kolo 1 13.08.2021 10:00 Tomislavgrad HNK TOMISLAV - HŠK POSUŠJE 0:5 14.08.2021 11:00 LJubuški NK LJUBUŠKI - HNK STOLAC 2:0 14.08.2021 12:30 ČITLUK HNK BROTNJO Čitluk - FK IGMAN 1:1 15.08.2021 18:00 Trebinje FK LEOTAR - HNK BRANITELJ 9:1 16.08.2021 18:00 NEUM HNK NEUM - HNK ČAPLJINA 2:0 18.08.2021 17:00 Grude HNK GRUDE - NK TROGLAV 1918 4:1 26.08.2021 18:00 GABELA NK GOŠK - FK VELEŽ 0:1 Kolo 2 20.08.2021 10:00 Posušje HŠK POSUŠJE - HNK BROTNJO Čitluk 4:0 21.08.2021 11:00 Stolac HNK STOLAC - NK GOŠK 0:0 21.08.2021 11:30 Mostar HNK BRANITELJ - NK LJUBUŠKI 2:2 21.08.2021 12:30 BUTUROVIĆ POLJE FK KLIS - HNK GRUDE 1:2 22.08.2021 09:30 ČAPLJINA HNK ČAPLJINA - FK LEOTAR 1:3 22.08.2021 19:00 Mostar FK VELEŽ - HNK TOMISLAV 2:2 27.08.2021 17:15 NEUM HNK NEUM - NK TROGLAV 1918 2:0 Kolo 3 27.08.2021 11:00 LJubuški NK LJUBUŠKI - HNK ČAPLJINA 3:1 28.08.2021 10:00 KONJIC FK IGMAN - HŠK POSUŠJE 2:2 28.08.2021 12:30 ČITLUK HNK BROTNJO Čitluk - FK VELEŽ 0:5 29.08.2021 11:00 GABELA NK GOŠK - HNK BRANITELJ 1:1 31.08.2021 17:00 Trebinje FK LEOTAR - NK TROGLAV 1918 6:1 01.09.2021 11:30 NEUM HNK NEUM - FK KLIS 3:0 01.09.2021 12:00 Tomislavgrad HNK TOMISLAV - HNK STOLAC 3:0 Kolo 4 04.09.2021 11:30 Livno NK TROGLAV 1918 - NK LJUBUŠKI 2:6 04.09.2021 12:00 Mostar FK VELEŽ - FK IGMAN 8:0 04.09.2021 12:00 Grude HNK GRUDE - HNK -

Bosnia and Herzegovina the Court of Bosnia And

THIS VERDICT SHALL BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA BECOME FINAL ON 19 THE COURT OF BOSNIA AND November 2010 HERZEGOVINA PRESIDENT OF THE PANEL S A R A J E VO JUDGE Criminal Division Goran Radević Section II for organized crime, economic crime and corruption Number: S1 2 K 003556 10 K ( Ref. X-K-08/511 ) Sarajevo, 19 November 2010 IN THE NAME OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA! The Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Criminal Trial Panel composed of Judge Goran Radević, as the President of the Trial Panel, and Judges Anđelko Marijanović and Fejzagić Esad as the members of the Panel, with the participation of the Legal Officer/Advisor Mirela Gadžo as the Record-taker, in the criminal case against the Accused DARIO BUŠIĆ from Sarajevo, following the Indictment of the Prosecutor's Office, number KT-191/07 of 4 January 2010, confirmed on 12 January 2010, filed for the grounded suspicion that he committed the criminal offense of Abuse of Office or Official Authority in violation of Article 220(3), in conjunction with paragraph 1 of the Criminal Code of BiH, which case was, pursuant to Article 26 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CPC BiH,) separated by the decision of Trial Panel held on the trial of 19 November 2010 from the case against the Accused NIKOLA ŠEGO, MIRKO ŠEKARA, ENIS AJKUNIĆ and RADOVAN DRAGAŠ, charged under the same Indictment of the Prosecutor’s Office of BiH with the same criminal offense, after the oral and public main trial attended by the Prosecutor of the Prosecutor’s Office of BiH, Dubravko Čampara, the Accused Dario Bušić and his Defense Counsels, -

Security Council Distr.: General 31 May 2001

United Nations S/2001/542 Security Council Distr.: General 31 May 2001 Original: English Letter dated 30 May 2001 from the Secretary-General addressed to the President of the Security Council I have the honour to convey the attached communication, dated 28 May 2001, which I have received from the Secretary-General of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. I should be grateful if you would bring it to the attention of the members of the Security Council. (Signed) Kofi A. Annan 01-39326 (E) 010601 *0139326* S/2001/542 Annex Letter dated 28 May 2001 from the Secretary-General of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization addressed to the Secretary-General In accordance with Security Council resolution 1088, I attach the monthly report on SFOR operations. I would appreciate your making the report available to the Security Council. (Signed) Lord Robertson of Port Ellen 2 S/2001/542 Enclosure Monthly report to the United Nations on SFOR operations 1. Over the reporting period (1 to 30 April 2001), there were just over 21,000 troops deployed in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatia, with contributions from all the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) allies and from 15 non-NATO countries. 2. On 3 April, an SFOR soldier died from injuries following an explosion during a minefield reconnaissance in Prozor. On 5 April, a school used mainly by Bosnian Serbs was destroyed in an explosion in Crni-Lug — explosives had been planted in the centre of the building — but no one was injured. 3. During the period under review, tension increased following the announcement of two important decisions, on the one hand by the High Representative on the establishment of provisional administration over the Hercegovacka Banka,a and on the other hand by the International Arbitrator on the final position of the Inter-Entity Boundary Line in the Dobrinja area. -

STREAMS of INCOME and JOBS: the Economic Significance of the Neretva and Trebišnjica River Basins

STREAMS OF INCOME AND JOBS: The Economic Significance of the Neretva and Trebišnjica River Basins CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 Highlights – The Value of Water for Electricity 5 Highlights – The Value of Water for Agriculture 8 Highlights – The Value of Public Water Supplie 11 Highlights – The Value of Water for Tourism 12 Conclusion: 13 BACKGROUND OF THE BASINS 15 METHODOLOGY 19 LAND USE 21 GENERAL CONTEXT 23 THE VALUE OF WATER FOR ELECTRICITY 29 Background of the Trebišnjica and Neretva hydropower systems 30 Croatia 33 Republika Srpska 35 Federation Bosnia and Herzegovina 37 Montenegro 40 Case study – Calculating electricity or revenue sharing in the Trebišnjica basin 41 Gap Analysis – Water for Electricity 43 THE VALUE OF WATER FOR AGRICULTURE 45 Federation Bosnia and Herzegovina 46 Croatia 51 Case study – Water for Tangerines 55 Case study – Wine in Dubrovnik-Neretva County 56 Case study – Wine in Eastern Herzegovina 57 Republika Srpska 57 Gap Analysis – Water for Agriculture 59 Montenegro 59 THE VALUE OF PUBLIC WATER SUPPLIES 63 Republika Srpska 64 Federation Bosnia and Herzegovina 66 Montenegro 68 Croatia 69 Gap Analysis – Public Water 70 THE VALUE OF WATER FOR TOURISM 71 Croatia 72 CONCLUSION 75 REFERENCES 77 1st edition Author/data analysis: Hilary Drew With contributions from: Zoran Mateljak Data collection, research, and/or translation support: Dr. Nusret Dresković, Nebojša Jerković, Zdravko Mrkonja, Dragutin Sekulović, Petra Remeta, Zoran Šeremet, and Veronika Vlasić Design: Ivan Cigić Published by WWF Adria Supported by the -

Monograph Natural-History Heritage of Tomislavgrad

Monograph Natural-history heritage of Tomislavgrad: An example of promotion, research and protection directions for Duvanjsko and Livanjsko polje Roman Ozimec & Marko Radoš Mara, NGO Naša baština (Our Heritage) The region of Tomislavgrad County covers 969 km2 and belongs partly to the Mediterranean, partly to the Alpine Biogeographical Region. Map by D. Radoš Photo by B. Stumberger 2 big karst poljes: Duvanjsko polje (112 km2) Buško blato, part of Livanjsko polje (405 km²) Smaller karst poljes: Dugo polje (19,1 km²), Roško polje (3,9 km²), Šujičko polje (2,7 km²), Viničko polje (2,2 km²)… 11 mountain massifs: Čvrsnica (2228 m), Vran (2074 m), Cincar (2006 m), Kamešnica (1856 m), Ljubuša (1797 m), Tušnica (1700 m), Jelovača (1527 m), Zavelim (1346 m), Lib (1328 m), Gvozd (1304 m) and Grabovica, with Midena (1224 m). Photo by M. Šumanović 2 lakes: Buško (55,92 km2) and Blidinjsko (up to 6 km2) Main river: Šujica (47,27 km): several small rivers: Drina, Miljacka, Ričina, Seget Hydrologicaly belong to Cetina river system, partly to Jadro, Žrnovnica, Vruja, also Vrljika (Neretva river system) Photo by I. Raič Photo by S.. Budimir Biško The basic idea was to establish an expert team of natural-history researches, who can create a synthesis of all aspects of the natural history heritage for a region, which is in this regard almost unknown. Project leaders: Society Naša baština (Our heritage) from Tomislavgrad (Bosnia and Herzegovina) and Zagreb (Croatia) Started at the end of 2009 and after 3,5 years of work in august 2013, Here is the Monograph on 615 pages and 1218 ilustrations Monograph is result of work: 4 members of editor counsel Robert Jolić, Roman Ozimec, Marko Radoš Mara, Vinko Vukadin 2 chief-editors Roman Ozimec, Marko Radoš Mara 3 reviewers Stipe Čuić (Tomislavgrad) Dr. -

A,B,C,E A,B,C,E a A,B,C,E A,B,C,E A,B,C,E A,B,C,E A,B,E A,B,E A,B,C,E A,B,E

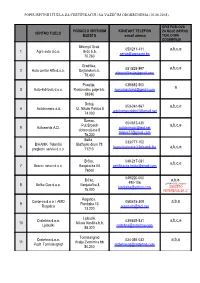

POPIS ISPITNIH TIJELA ZA CERTIFIKACIJU SA VAŽEĆIM ODOBRENJIMA (03.06.2018) OPIS POSLOVA PODACI O ISPITNOM KONTAKT TELEFON ZA KOJE ISPITNO ISPITNO TIJELO MJESTU e-mail adresa TIJELO IMA ODOBRENJE Mrkonjić Grad, 050/211-411 a,b,c,e 1 Agro auto d.o.o. Brdo b.b. [email protected] 70.260 Gradiška, a,b,c,e 2 Auto centar Alfa d.o.o. Dejtonska b.b. 051/825-997 [email protected] 78.400 Posušje, 039/682-900 a 3 Auto-Inđilović d.o.o. Rastovačko polje b.b. [email protected] 88240 Doboj, 053-241-967 a,b,c,e 4 Autokomerc a.d. Ul. Nikole Pašića 5 [email protected] 74.000 Šamac, 054/612-435 Put Srpskih a,b,c,e 5 Autoservis A.D. [email protected] dobrovoljaca 8 [email protected] 76.230 Ilidža, 033/777-102 BIHAMK- Tehnički Blažujski drum 78 6 [email protected] pregledi i servisi d.o.o. 71210 a,b,c,e Brčko, 049-217-081 a,b,c,e 7 Braco i sinovi d.o.o. Banjalučka 54 [email protected] 76000 049/220-000 Brčko, a,b,e 490-106 za M1,N1,O1,O2,L kategoriju 8 Brčko Gas d.o.o. Banjalučka 8 [email protected] ODUZETO 76.000 ODOBRENJE ZA „C“ Rogatica, Conte-co d.o.o. i AMD 058/415-309 a,b,e 9 Pionirska 13 Rogatica [email protected] 73.220 Ljubuški, Crotehna d.o.o. 039/839-531 a,b,c,e 10 Nikole Kordića b.b. Ljubuški [email protected] 88.320 Tomislavgrad Crotehna d.o.o. -

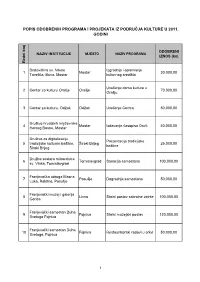

Popis Odobrenih Programa I Projekata Iz Područja

POPIS ODOBRENIH PROGRAMA I PROJEKATA IZ PODRUČJA KULTURE U 2011. GODINI ODOBRENI NAZIV INSTITUCIJE MJESTO NAZIV PROGRAMA IZNOS (kn) Redni broj Bratovština sv. Nikole Izgradnja i opremanje 1 Mostar 30.000,00 Tavelića, Buna, Mostar kulturnog središta Uređenje doma kulture u 2 Centar za kulturu Orašje Orašje 70.000,00 Orašju 3 Centar za kulturu, Odžak Odžak Uređenje Centra 50.000,00 Društvo hrvatskih književnika 4 Mostar Izdavanje časopisa Osvit 40.000,00 Herceg Bosne, Mostar Društvo za digitalizaciju Prezentacija tradicijske 5 tradicijske kulturne baštine, Široki Brijeg 25.000,00 baštine Široki Brijeg Družba sestara milosrdnica 6 Tomislavgrad Sanacija samostana 100.000,00 sv. Vinka, Tomislavgrad Franjevačka udruga Masna 7 Posušje Dogradnja samostana 50.000,00 Luka, Rakitno, Posušje Franjevački muzej i galerija 8 Livno Stalni postav sakralne zbirke 100.000,00 Gorica Franjevački samostan Duha 9 Fojnica Stalni muzejski postav 120.000,00 Svetoga Fojnica Franjevački samostan Duha 10 Fojnica Restauratorski radovi u crkvi 50.000,00 Svetoga, Fojnica 1 ODOBRENI NAZIV INSTITUCIJE MJESTO NAZIV PROGRAMA IZNOS (kn) Redni broj Franjevački samostan Guča 11 Guča Gora Zaštita spomeničke građe 50.000,00 Gora Franjevački samostan 12 Banja Luka Obnova porušene crkve 80.000,00 Petrićevac, Banja Luka Franjevački samostan sv. Dovršetak obnove 13 Konjic 100.000,00 Ivana Krstitelja, Konjic samostana Franjevački samostan sv. Kraljeva 14 Ivana Krstitelja, Kraljeva Zaštita matičnih knjiga 80.000,00 Sutjeska Sutjeska Franjevački samostan sv. 15 Jajce Sanacija muzeja