Frank Conroy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Power Stronger Than Itself

A POWER STRONGER THAN ITSELF A POWER STRONGER GEORGE E. LEWIS THAN ITSELF The AACM and American Experimental Music The University of Chicago Press : : Chicago and London GEORGE E. LEWIS is the Edwin H. Case Professor of American Music at Columbia University. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2008 by George E. Lewis All rights reserved. Published 2008 Printed in the United States of America 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-47695-7 (cloth) ISBN-10: 0-226-47695-2 (cloth) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lewis, George, 1952– A power stronger than itself : the AACM and American experimental music / George E. Lewis. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ), discography (p. ), and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-226-47695-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-226-47695-2 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians—History. 2. African American jazz musicians—Illinois—Chicago. 3. Avant-garde (Music) —United States— History—20th century. 4. Jazz—History and criticism. I. Title. ML3508.8.C5L48 2007 781.6506Ј077311—dc22 2007044600 o The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992. contents Preface: The AACM and American Experimentalism ix Acknowledgments xv Introduction: An AACM Book: Origins, Antecedents, Objectives, Methods xxiii Chapter Summaries xxxv 1 FOUNDATIONS AND PREHISTORY -

52 Literary Journalism Studies, Vol. 8, No. 1, Spring 2016

52 Literary Journalism Studies, Vol. 8, No. 1, Spring 2016 Above: Author Tracy Kidder. Photograph by Gabriel Amadeus Cooney. Right: Author John D’Agata. 53 Beyond the Program Era: Tracy Kidder, John D’Agata, and the Rise of Literary Journalism at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop David Dowling University of Iowa, United States Abstract: The Iowa Writers’ Workshop’s influence on literary journalism -ex tends beyond instructional method to its production of two writers who al- ternately sustained the traditions of the genre and boldly defied them: Tracy Kidder, who forged his career during the heyday of the New Journalism in the early 1970s, and John D’Agata, today’s most controversial author chal- lenging the boundaries of literary nonfiction. This essay examines the key works of Kidder and D’Agata as expressions of and reactions to Tom Wolfe’s exhortation for a new social realism and literary renaissance fusing novelis- tic narrative with journalistic reporting and writing. Whereas a great deal of attention has been paid to Iowa’s impact on the formation of the postwar literary canon in poetry and fiction, its profound influence on literary jour- nalism within the broader world of creative writing has received little no- tice. Through archival research, original interviews, and textual explication, I argue that Kidder’s narrative nonfiction reinforces Wolfe’s conception of social realism, as theorized in “Stalking the Billion-Footed Beast,” in sharp contrast to D’Agata’s self-reflexive experimentation, toward a more liber- ally defined category of creative writing. Norman Sims defended literary journalists’ immersion in “complex, difficult subjects” and narration “with a voice that allows complexity and contradiction,” countering critics who claimed their work “was not always accurate.” D’Agata has reopened the de- bate by exposing the narrative craft’s fraught and turbulent relation to fact. -

Application for Iowa City, Iowa, Usa to the Unesco Creative Cities Network

APPLICATION FOR IOWA CITY, IOWA, USA TO THE UNESCO CREATIVE CITIES NETWORK submitted on december 19, 2007 by the literary community of iowa city The Iowa Writers’ Workshop developed out of an idea, originally implemented in 896 at the University of Iowa, to teach “Verse Making.” By the 90s, the university had taken the radical step of granting graduate student credit for creative work. In 94, the first Master of Fine Arts degree in Creative Writing was awarded. By the end of that decade, Flannery O’Connor was a member of the Workshop, which was fast becoming a national institution… . The Workshop jettisoned genius and ignored literary theory because, like the centuries-old tradition of rhetoric, it believed in the words of Paul Engle, that writing was a “form of activity inseparable from the wider social relations between writers and readers,” and that the nurture and love of literature could “materially affect American culture.” Tom Grimes, The Workshop creative theme: Literature point person: Christopher Merrill Director International Writing Program Shambaugh House 430 N. Clinton Iowa City, Iowa 52242 management team: Christopher Merrill, Director, International Writing Program Russell Valentino, Director, Autumn Hill Books Amy Margolis, Director, Iowa Summer Writing Festival Steering Committee: Ethan Canin, Novelist and Professor, Writers Workshop, UI Jim Harris, Owner, Prairie Lights Bookstore Susan Shullaw, Vice President, UI Foundation Jonathan Wilcox, Chair, English Department, UI James Elmborg, Chair, School of Library Science Alan MacVey, Director, Theater Department, UI Robin Hemley, Director, Nonfiction Writing Program, UI Ross Wilburn, Mayor, Iowa City Dale Helling, Interim City Manager, Iowa City Joshua Schamberger, President, Iowa City/Coralville Convention and Visitors Bureau Contents i. -

The Rise of Creative Writing and the New Value of Creativity

THE RISE OF CREATIVE WRITING AND THE NEW VALUE OF CREATIVITY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY STEPHEN PETER HEALEY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THOMAS AUGST, CO-ADVISER; MARIA DAMON, CO-ADVISER JUNE 2009 Copyright, Stephen Peter Healey, June 2009 Acknowledgements “Movement 1.0 Thinking Outside Creative Writing” published as “The Rise of Creative Writing and the New Value of Creativity” in The Writer’s Chronicle , February 2009 (Volume 41, Number 4). i Table of Contents Prelude 0.0 The Most Beautiful Box of Cereal……………………………………………1 Movement 1.0 Thinking Outside Creative Writing…………………………………2 Interlude 1.1 Minus Sign……………………………………………………………………26 Movement 1.1 What Is Creative Literacy?..............................................................28 Interlude 2.0 A Genealogy of My Desire as a Creative Writing Student……………..44 Movement 2.0 A Genealogy of the Workshop……………………………………..58 Interlude 2.1 Among the Most Well-Educated Motherfuckers………………………….82 Movement 2.1 Workshop War Stories……………………………………………..83 Interlude 3.0 The Laws of Raining ………………………………………………….133 Movement 3.0 Creativity on the Inside: A Prison Pedagogy…………………….134 Interlude 4.0 The Corrected Text…………………………………………………………186 Movement 4.0 From Workshop to Collaborative Practice……………………….188 Interlude 5.0 Creative Consultant………………………………………………………..213 Movement 5.0 Advertising, Poetry, and American Contradiction……………….223 Interlude 5.1 The Ghost of My Candy……………………………………………………233 -

Arts&Sciences

College of Liberal Arts and Sciences 240 Schaeffer Hall November- The University of Iowa DANCE GALA: 25 IN 2005 Iowa City, Iowa 52242-1409 With the UI Chamber Orchestra , Department of Dance and School of Music, Division of E-mail: [email protected] Performing Arts Visit the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences December at www.clas.uiowa.edu WINTER COMMENCEMENT March-& - Arts&Sciences THE PUZZLE LOCKER FALL 2005 By W. David Hancock Arts & Sciences is published for alumni and friends of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Department of Theatre Arts, Division of at The University of Iowa. It is produced by the Offi ce of the Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and by the Offi ce of University Relations Publications. Performing Arts Address changes: Readers who wish to change their mailing address for April & Arts & Sciences may call Alumni Records at 319-335-3297 or 800-469-2586; SPRING OPERA: THE CRUCIBLE or send an e-mail to [email protected]. By Arthur Miller (story) and Robert Ward (music) With the UI Chamber Orchestra, School of DEAN Linda Maxson Music, and Martha-Ellen Tye Opera Theater, E XECUTIVE EDITOR Carla Carr Division of Performing Arts M ANAGING EDITOR Linda Ferry May CONSULTING EDITOR Barbara Yerkes SPRING COMMENCEMENT DESIGNER Anne Kent June - P HOTOGRAPHER Tom Jorgensen A LUMNI REUNION WEEKEND CONTRIBUTING FEATURE WRITERS Peter Alexander, Nic Arp, Winston Barclay, Honor classes: 1946, 1956, 1961, 1966 Russell Ciochon, Lori Erickson, Jean C. Florman, UI Alumni Association Distinguished Alumni Gary W. Galluzzo, Lin Larson, Sara Epstein Moninger, David Pedersen, Stephen Pradarelli Award ceremony COVER PHOTO: James Sanborn’s cylindrical October - sculpture “Iacto” stands at the main entrance to the Philip D. -

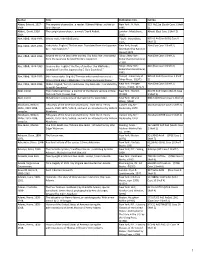

PRPL Master List 6-7-21

Author Title Publication Info. Call No. Abbey, Edward, 1927- The serpents of paradise : a reader / Edward Abbey ; edited by New York : H. Holt, 813 Ab12se (South Case 1 Shelf 1989. John Macrae. 1995. 2) Abbott, David, 1938- The upright piano player : a novel / David Abbott. London : MacLehose, Abbott (East Case 1 Shelf 2) 2014. 2010. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Warau tsuki / Abe Kōbō [cho]. Tōkyō : Shinchōsha, 895.63 Ab32wa(STGE Case 6 1975. Shelf 5) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Hakootoko. English;"The box man. Translated from the Japanese New York, Knopf; Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) by E. Dale Saunders." [distributed by Random House] 1974. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Beyond the curve (and other stories) / by Kobo Abe ; translated Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) from the Japanese by Juliet Winters Carpenter. Kodansha International, c1990. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Tanin no kao. English;"The face of another / by Kōbō Abe ; Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) [translated from the Japanese by E. Dale Saunders]." Kodansha International, 1992. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Bō ni natta otoko. English;"The man who turned into a stick : [Tokyo] : University of 895.62 Ab33 (East Case 1 Shelf three related plays / Kōbō Abe ; translated by Donald Keene." Tokyo Press, ©1975. 2) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Mikkai. English;"Secret rendezvous / by Kōbō Abe ; translated by New York : Perigee Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) Juliet W. Carpenter." Books, [1980], ©1979. Abel, Lionel. The intellectual follies : a memoir of the literary venture in New New York : Norton, 801.95 Ab34 Aa1in (South Case York and Paris / Lionel Abel.