Art Learning Resource – Historic Art Collections Introduction Art Learning Resource – Historic Art Collections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1934 Exhibition Catalogue Pdf, 1.23 MB

~ i Royal Cambrian Academy of Art, t PL:\S MAWR, CON\\'AY. t Telephone, No. 113 Conway. i CATALOGUE i OF THE I FIFTY-SECOND ANNUAL i EXHIB ITION, 1934. ~ i The Exhibition will be open from 21st May to I ~ 26th September. A dmission (including Enter- .( ,r tainment Tax), Adults, 7d. Children under 14, ~ ltd. Season Tickets, 2 /(i. 1' ,q·~~"-"15'~ <:..i!w~~~~~~~~\:I R. E. Jones & Bros., Pri11te1·s, Conway. 1 HONORARY MEMBERS. ', The Presidents of the following Academies and Societies :- - Royal Academy of Arts, London (Sir W. Llewelyn, G.C.V.O ., R.I., R.W.A.). ii Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh (George Pirie, Esq). Royal Hibernian Academy, Dublin (Dermod O'Brien, Esq.,H.R.A., H.R.S.A.). tbe Royal Cambrian Rccldemy or Jlrf, F. Brangwyn, Esq., R.A., H.R.S.A., R.E., R.W.A., A.R.W.S. INSTITUTED 1881. Sir W. Goscombe John, R.A. Terrick Williams, Esq., R .A., F'.R.I., R.O.I., R.W.A., V.P.R.13.C. Sir Herbert Baker, R.A., F.R.I.B.A. PATRONS. FOUNDERS. HIS MAJESTY THE KING W. Laurence Banks, J .P. HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN Sir Cuthbert Grundy, R.C.A., R.I., R.W.A., V.P.R.13.C. , . HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS THE PRINCE J. R. G. Grundy, R.C.A. OF WALES Anderson Hague, V .P .R.C.A., R.I., R.O.I. E. A. Norbury, R.C.A. Charles Potter, R.C.A. I, I, H. Clarence Whaite, P.R.C.A., R.W.S. -

Eighteenth-Century English and French Landscape Painting

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2018 Common ground, diverging paths: eighteenth-century English and French landscape painting. Jessica Robins Schumacher University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Schumacher, Jessica Robins, "Common ground, diverging paths: eighteenth-century English and French landscape painting." (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3111. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3111 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMON GROUND, DIVERGING PATHS: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING By Jessica Robins Schumacher B.A. cum laude, Vanderbilt University, 1977 J.D magna cum laude, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville, 1986 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art (C) and Art History Hite Art Department University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2018 Copyright 2018 by Jessica Robins Schumacher All rights reserved COMMON GROUND, DIVERGENT PATHS: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING By Jessica Robins Schumacher B.A. -

Constable, Gainsborough, Turner and the Making of Landscape

CONSTABLE, GAINSBOROUGH, TURNER AND THE MAKING OF LANDSCAPE THE JOHN MADEJSKI FINE ROOMS 8 December 2012 – 17 February 2013 This December an exhibition of works by the three towering figures of English landscape painting, John Constable RA, Thomas Gainsborough RA and JMW Turner RA and their contemporaries, will open in the John Madejski Fine Rooms and the Weston Rooms. Constable, Gainsborough, Turner and the Making of Landscape will explore the development of the British School of Landscape Painting through the display of 120 works of art, comprising paintings, prints, books and archival material. Since the foundation of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1768, its Members included artists who were committed to landscape painting. The exhibition draws on the Royal Academy’s Collection to underpin the shift in landscape painting during the 18 th and 19 th centuries. From Founder Member Thomas Gainsborough and his contemporaries Richard Wilson and Paul Sandby, to JMW Turner and John Constable, these landscape painters addressed the changing meaning of ‘truth to nature’ and the discourses surrounding the Beautiful, the Sublime and the Picturesque. The changing style is represented by the generalised view of Gainsborough’s works and the emotionally charged and sublime landscapes by JMW Turner to Constable’s romantic scenes infused with sentiment. Highlights include Gainsborough’s Romantic Landscape (c.1783), and a recently acquired drawing that was last seen in public in 1950. Constable’s two great landscapes of the 1820s, The Leaping Horse (1825) and Boat Passing a Lock (1826) will be hung alongside Turner’s brooding diploma work, Dolbadern Castle (1800). -

Cardiff 19Th Century Gameboard Instructions

Cardiff 19th Century Timeline Game education resource This resource aims to: • engage pupils in local history • stimulate class discussion • focus an investigation into changes to people’s daily lives in Cardiff and south east Wales during the nineteenth century. Introduction Playing the Cardiff C19th timeline game will raise pupil awareness of historical figures, buildings, transport and events in the locality. After playing the game, pupils can discuss which of the ‘facts’ they found interesting, and which they would like to explore and research further. This resource contains a series of factsheets with further information to accompany each game board ‘fact’, which also provide information about sources of more detailed information related to the topic. For every ‘fact’ in the game, pupils could explore: People – Historic figures and ordinary population Buildings – Public and private buildings in the Cardiff locality Transport – Roads, canals, railways, docks Links to Castell Coch – every piece of information in the game is linked to Castell Coch in some way – pupils could investigate those links and what they tell us about changes to people’s daily lives in the nineteenth century. Curriculum Links KS2 Literacy Framework – oracy across the curriculum – developing and presenting information and ideas – collaboration and discussion KS2 History – skills – chronological awareness – Pupils should be given opportunities to use timelines to sequence events. KS2 History – skills – historical knowledge and understanding – Pupils should be given -

Chapter Eleven

Chapter eleven he greater opportunities for patronage and artistic fame that London could offer lured many Irish artists to seek their fortune. Among landscape painters, George Barret was a founding Tmember of the Royal Academy; Robert Carver pursued a successful career painting scenery for the London theatres and was elected President of the Society of Artists while, even closer to home, Roberts’s master George Mullins relocated to London in 1770, a year after his pupil had set up on his own in Dublin – there may even have been some connection between the two events. The attrac- tions of London for a young Irish artist were manifold. The city offered potential access to ever more elevated circles of patronage and the chance to study the great collections of old masters. Even more fundamental was the febrile artistic atmosphere that the creation of the Royal Academy had engen- dered; it was an exciting time to be a young ambitious artist in London. By contrast, on his arrival in Dublin in 1781, the architect James Gandon was dismissive of the local job prospects: ‘The polite arts, or their professors, can obtain little notice and less encouragement amidst such conflicting selfish- ness’, a situation which had led ‘many of the highly gifted natives...[to] seek for personal encourage- ment and celebrity in England’.1 Balancing this, however, Roberts may have judged the market for landscape painting in London to be adequately supplied. In 1769, Thomas Jones, himself at an early stage at his career, surveyed the scene: ‘There was Lambert, & Wilson, & Zuccarelli, & Gainsborough, & Barret, & Richards, & Marlow in full possession of landscape business’.2 Jones concluded that ‘to push through such a phalanx required great talents, great exertions, and above all great interest’.3 As well as the number of established practitioners in the field there was also the question of demand. -

Lowell Libson Limited

LOWELL LI BSON LTD 2 0 1 0 LOWELL LIBSON LIMITED BRITISH PAINTINGS WATERCOLOURS AND DRAWINGS 3 Clifford Street · Londonw1s 2lf +44 (0)20 7734 8686 · [email protected] www.lowell-libson.com LOWELL LI BSON LTD 2 0 1 0 Our 2010 catalogue includes a diverse group of works ranging from the fascinating and extremely rare drawings of mid seventeenth century London by the Dutch draughtsman Michel 3 Clifford Street · Londonw1s 2lf van Overbeek to the small and exquisitely executed painting of a young geisha by Menpes, an Australian, contained in the artist’s own version of a seventeenth century Dutch frame. Telephone: +44 (0)20 7734 8686 · Email: [email protected] Sandwiched between these two extremes of date and background, the filling comprises Website: www.lowell-libson.com · Fax: +44 (0)20 7734 9997 some quintessentially British works which serve to underline the often forgotten international- The gallery is open by appointment, Monday to Friday ism of ‘British’ art and patronage. Bellucci, born in the Veneto, studied in Dalmatia, and worked The entrance is in Old Burlington Street in Vienna and Düsseldorf before being tempted to England by the Duke of Chandos. Likewise, Boitard, French born and Parisian trained, settled in London where his fluency in the Rococo idiom as a designer and engraver extended to ceramics and enamels. Artists such as Boitard, in the closely knit artistic community of London, provided the grounding of Gainsborough’s early In 2010 Lowell Libson Ltd is exhibiting at: training through which he synthesised -

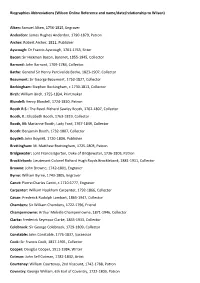

Biographies Abbreviations (Wilson Online Reference and Name/Date/Relationship to Wilson)

Biographies Abbreviations (Wilson Online Reference and name/date/relationship to Wilson) Alken: Samuel Alken, 1756-1815, Engraver Anderdon: James Hughes Anderdon, 1790-1879, Patron Archer: Robert Archer, 1811, Publisher Ayscough: Dr Francis Ayscough, 1701-1763, Sitter Bacon: Sir Hickman Bacon, Baronet, 1855-1945, Collector Barnard: John Barnard, 1709-1784, Collector. Bathe: General Sir Henry Percival de Bathe, 1823-1907, Collector Beaumont: Sir George Beaumont, 1753-1827, Collector Beckingham: Stephen Beckingham, c.1730-1813, Collector Birch: William Birch, 1755-1834, Printmaker Blundell: Henry Blundell, 1724-1810, Patron Booth R.S.: The Revd. Richard Sawley Booth, 1762-1807, Collector Booth, E.: Elizabeth Booth, 1763-1819, Collector Booth, M: Marianne Booth, Lady Ford, 1767-1849, Collector Booth: Benjamin Booth, 1732-1807, Collector Boydell: John Boydell, 1720-1804, Publisher Brettingham: M. Matthew Brettingham, 1725-1803, Patron Bridgewater: Lord Francis Egerton, Duke of Bridgewater, 1736-1803, Patron Brocklebank: Lieutenant Colonel Richard Hugh Royds Brocklebank, 1881-1911, Collector Browne: John Browne, 1742-1801, Engraver Byrne: William Byrne, 1743-1805, Engraver Canot: Pierre-Charles Canot, c.1710-1777, Engraver Carpenter: William Hookham Carpenter, 1792-1866, Collector Cavan: Frederick Rudolph Lambart, 1865-1947, Collector Chambers: Sir William Chambers, 1722-1796, Friend Champernowne: Arthur Melville Champernowne, 1871-1946, Collector Clarke: Frederick Seymour Clarke, 1855-1933, Collector Colebrook: Sir George Colebrook, 1729-1809, Collector Constable: John Constable, 1776-1837, Successor Cook: Sir Francis Cook, 1817-1901, Collector Cooper: Douglas Cooper, 1911-1984, Writer Cotman: John Sell Cotman, 1782-1842, Artist Courtenay: William Courtenay, 2nd Viscount, 1742-1788, Patron Coventry: George William, 6th Earl of Coventry, 1722-1809, Patron Dartmouth: William Legge, 2nd Earl of Dartmouth, 1731-1801, Patron Daulby: Daniel Daulby, d. -

Laboratories of Creativity : the Alma-Tademas' Studio-Houses and Beyond

This is a repository copy of Laboratories of Creativity : The Alma-Tademas' Studio-Houses and Beyond. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/134913/ Version: Published Version Article: (2018) Laboratories of Creativity : The Alma-Tademas' Studio-Houses and Beyond. British Art Studies. 10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-09/conversation Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial (CC BY-NC) licence. This licence allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, and any new works must also acknowledge the authors and be non-commercial. You don’t have to license any derivative works on the same terms. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ British Art Studies Summer 2018 British Art Studies Issue 9, published 7 August 2018 Cover image: Jonathan Law, Pattern, excerpt from ilm, 2018.. Digital image courtesy of Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art with support from the staf of Leighton House Museum, The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. PDF generated on 7 August 2018 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading oline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identiiers) provided within the online article. -

Nathaniel Hitch and the Making of Church Sculpture Claire Jones

Nathaniel Hitch and the Making of Church Sculpture Claire Jones Housed at the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds is the archive of the now little-known sculptor, architectural sculptor, and sculptor’s modeller, Nathaniel Hitch (1845–1938).1 Unlike the extensive manuscript, printed, and visual material in Hamo Thornycroft’s archive, also held at the Henry Moore Institute, Hitch’s consists of hundreds of photographs pasted into two albums. These demonstrate the range of sculptural activity undertaken by Hitch, including figurative work, architectural sculpture, and anima- lier sculpture. Above all, they represent sculpture intended for Christian places of worship: recumbent effigies; altars; free-standing figures of saints, bishops, and biblical figures; reliefs of biblical scenes; Christ on the cross; Christ in groups; the Virgin Mary and Child; and sculpture for church fur- niture and furnishings. Hitch’s archive therefore offers significant docu- mentation for the study of Victorian sculpture practice outside the more familiar areas of the Academy and ideal classical sculpture: namely, church sculpture. The photographs are taken within Hitch’s studio or workshop. The space itself is only fragmentarily visible, and the sculptor himself is noticea- bly absent from all the photographs. This is distinct to the ‘at home’ and ‘in studio’ photographs of society sculptors such as Thornycroft, which recent scholarship has usefully examined in terms of the private-public domain of the artist’s studio and the role of these studios and photographs in an I would like to thank Claire Mayoh, archivist at the Henry Moore Institute, her maternity cover Janette Martin, and Georgia Goldsmith at the Bulldog Trust for assisting me in my research and for kindly providing the images for this publication. -

University of Birmingham Animals in the Studio House

University of Birmingham Animals in the Studio House Nichols, Eleanor DOI: 10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-09/conversation/016 License: Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial (CC BY-NC) Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (Harvard): Nichols, E 2018, 'Animals in the Studio House', British Art Studies, vol. Summer 2018, no. 9. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-09/conversation/016 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

Swansea University Open Access Repository

Cronfa - Swansea University Open Access Repository _____________________________________________________________ This is an author produced version of a paper published in: Cylchgrawn Hanes y Methodistiaid Calfinaidd Cronfa URL for this paper: http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa50026 _____________________________________________________________ Paper: Matthews, G. (2019). Angels, Doves and Minerva: Reading the memorials to the Great War in Welsh Presbyterian chapels. Cylchgrawn Hanes y Methodistiaid Calfinaidd, 42, 72-91. _____________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence. Copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ Angels, Doves and Minerva: Reading the memorials to the Great War in Welsh Presbyterian chapels The starting point for this lecture is the premise that war memorials are interesting. They were important for those who went to the trouble of commissioning and creating them, and they were important for the relatives and friends of those whose names were commemorated upon them. Each individual memorial has its own messages – even the plainest and simplest memorial will have some feature that is worthy of further consideration. -

Minutes Template

143 THE COUNTY COUNCIL OF THE CITY & COUNTY OF CARDIFF The County Council of the City & County of Cardiff met at County Hall, Cardiff on 20 October 2016 to transact the business set out in the Council summons dated 14 October 2016. Present: County Councillor Walsh (Lord Mayor of City & County of Cardiff). County Councillors Ali Ahmed, Aubrey, Bale, Bowden, Boyle, Bradbury, Bridges, Carter, Chaundy, Clark, Richard Cook, Cowan, De'Ath, Derbyshire, Elsmore, Evans, Ford, Goddard, Goodway, Gordon, Graham, Hill-John, Hinchey, Howells, Hudson, Hunt, Hyde, Keith Jones, Margaret Jones, Joyce, Kelloway, Knight, Lent, Lloyd, Marshall, McEvoy, McGarry, McKerlich, Merry, Michael, Mitchell, Murphy, Parry, Patel, Phillips, Dianne Rees, Robson, Sanders, Simmons, Stubbs, Thomas, Ben Thomas, Graham Thomas, Lynda Thorne, Walker, Weaver, White, Wild, Darren Williams and Woodman 83 : APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE Apologies for absence had been received from Councillors Manzoor Ahmed, Dilwar Ali, Burfoot, Ralph Cook, Kirsty Davies-Warner, Chris Davis, Govier, Groves, Holden, Magill, Derrick Morgan and David Rees. 84 : DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST The following declarations of interest were declared: - Councillor Interest Councillor Ali Ahmed Item 7: Supplementary Planning Guidance – Houses in Multiple Occupation – Personal interest in an HMO. Councillor Hudson Item 6 : City of Cardiff Council Annual Improvement Report and Item 9: Cabinet Member Health, Housing and wellbeing Statement - Personal interest as family member in receipt of Disabled Facilities. Councillor Kelloway Item 7: Supplementary Planning Guidance – Houses in Multiple Occupation – Personal interest in an HMO. Councillor Woodman Item 9: Cabinet Member Health, Housing and Wellbeing Statement - Personal interest a Member of the Management Board of the Goldies Cymru Charity.