Visitors to College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gothic Riffs Anon., the Secret Tribunal

Gothic Riffs Anon., The Secret Tribunal. courtesy of the sadleir-Black collection, University of Virginia Library Gothic Riffs Secularizing the Uncanny in the European Imaginary, 1780–1820 ) Diane Long hoeveler The OhiO STaTe UniverSiT y Press Columbus Copyright © 2010 by The Ohio State University. all rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data hoeveler, Diane Long. Gothic riffs : secularizing the uncanny in the european imaginary, 1780–1820 / Diane Long hoeveler. p. cm. includes bibliographical references and index. iSBn-13: 978-0-8142-1131-1 (cloth : alk. paper) iSBn-10: 0-8142-1131-3 (cloth : alk. paper) iSBn-13: 978-0-8142-9230-3 (cd-rom) 1. Gothic revival (Literature)—influence. 2. Gothic revival (Literature)—history and criticism. 3. Gothic fiction (Literary genre)—history and criticism. i. Title. Pn3435.h59 2010 809'.9164—dc22 2009050593 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (iSBn 978-0-8142-1131-1) CD-rOM (iSBn 978-0-8142-9230-3) Cover design by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe. Type set in adobe Minion Pro. Printed by Thomson-Shore, inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the american national Standard for information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSi Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is for David: January 29, 2010 Riff: A simple musical phrase repeated over and over, often with a strong or syncopated rhythm, and frequently used as background to a solo improvisa- tion. —OED - c o n t e n t s - List of figures xi Preface and Acknowledgments xiii introduction Gothic Riffs: songs in the Key of secularization 1 chapter 1 Gothic Mediations: shakespeare, the sentimental, and the secularization of Virtue 35 chapter 2 Rescue operas” and Providential Deism 74 chapter 3 Ghostly Visitants: the Gothic Drama and the coexistence of immanence and transcendence 103 chapter 4 Entr’acte. -

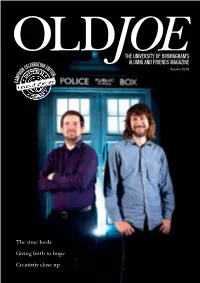

Old Joe Autumn 2015

OLDJOETHE UNIVERSITY OF BIRMINGHAM’S ALUMNI AND FRIENDS MAGAZINE Autumn 2015 The time lords Giving birth to hope Creativity close up 2 OLD JOE THE FIRST WORD The firstword This special edition of Old Joe magazine celebrates something truly extraordinary; GUEST EDITOR the University’s pioneering Circles of Influence fundraising campaign raising Each year Birmingham has many an astounding £193,426,877.47 million. reasons to celebrate, and this year Circles of Influence substantially has been no different. The Circles exceeded its £160 million target to of Influence campaign has officially become the largest charitable campaign raised £193.4 million, funding outside Oxford, London, and Cambridge, extraordinary projects on campus, and this was only possible through the locally and globally (page 8). kindness and generosity of our donors I am honoured to represent the and volunteers. University by graduating as its From completing the Aston Webb semi-circle with the Bramall Music Building symbolic 300,000th alumna (page to funding life-saving cancer research, the campaign has left a wonderful legacy 36). Being part of this momentous to the University and the impact of donors’ gifts will be felt for years to come. From occasion has been a fantastic way to our very conception as England’s first civic university more than a century ago, end my three years as an Birmingham has been founded through philanthropy and our donors’ generosity is undergraduate. I have thoroughly keeping that vision strong. enjoyed my time here. Inside this magazine, you can read how our extraordinary campaign has changed During my final year I was treasurer thousands of people’s lives, and learn more about some of the exciting new areas of the Women in Finance society, so addressing society’s biggest challenges where our fundraising will now focus, it was inspiring to read alumna Billie from saving mothers’ lives in Africa to innovative new cancer treatments. -

Cairncross Review a Sustainable Future for Journalism

THE CAIRNCROSS REVIEW A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE FOR JOURNALISM 12 TH FEBRUARY 2019 Contents Executive Summary 5 Chapter 1 – Why should we care about the future of journalism? 14 Introduction 14 1.1 What kinds of journalism matter most? 16 1.2 The wider landscape of news provision 17 1.3 Investigative journalism 18 1.4 Reporting on democracy 21 Chapter 2 – The changing market for news 24 Introduction 24 2.1 Readers have moved online, and print has declined 25 2.2 Online news distribution has changed the ways people consume news 27 2.3 What could be done? 34 Chapter 3 – News publishers’ response to the shift online and falling revenues 39 Introduction 39 3.1 The pursuit of digital advertising revenue 40 Case Study: A Contemporary Newsroom 43 3.2 Direct payment by consumers 48 3.3 What could be done 53 Chapter 4 – The role of the online platforms in the markets for news and advertising 57 Introduction 57 4.1 The online advertising market 58 4.2 The distribution of news publishers’ content online 65 4.3 What could be done? 72 Cairncross Review | 2 Chapter 5 – A future for public interest news 76 5.1 The digital transition has undermined the provision of public-interest journalism 77 5.2 What are publishers already doing to sustain the provision of public-interest news? 78 5.3 The challenges to public-interest journalism are most acute at the local level 79 5.4 What could be done? 82 Conclusion 88 Chapter 6 – What should be done? 90 Endnotes 103 Appendix A: Terms of Reference 114 Appendix B: Advisory Panel 116 Appendix C: Review Methodology 120 Appendix D: List of organisations met during the Review 121 Appendix E: Review Glossary 123 Appendix F: Summary of the Call for Evidence 128 Introduction 128 Appendix G: Acknowledgements 157 Cairncross Review | 3 Executive Summary Executive Summary “The full importance of an epoch-making idea is But the evidence also showed the difficulties with often not perceived in the generation in which it recommending general measures to support is made.. -

THE NEWZOOM Does Journalism Need Offices? Contents

MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL UNION OF JOURNALISTS WWW.NUJ.ORG.UK | OCTOBER-NOVEMBER 2020 THE NEWZOOM Does journalism need offices? Contents Main feature 12 News from the home front Is the end of the office nigh? News he coronavirus pandemic is changing 03 Thousands of job cuts take effect the way we live and work radically. Not least among the changes is our Union negotiates redundancies widespread working from home and 04 Fury over News UK contracts the broader question of how much we Photographers lose rights Tneed an office. Some businesses are questioning whether they need one at all, others are looking 05 Bullivant strike saves jobs towards a future of mixed working patterns with some Management enters into talks homeworking and some office attendance. In our cover feature 06 TUC Congress Neil Merrick looks at what this means for our industry. Reports from first virtual meeting Also in this edition of The Journalist we have a feature on how virtual meetings are generating more activity in branches “because the meetings are now more accessible. Edinburgh Features Freelance branch has seen a big jump in people getting 10 Behind closed doors involved, has increased the frequency of its meetings and has Reporting the family courts linked up with other branches for joint meetings. Recently, the TUC held its first virtual conference. We have full 14 News takes centre stage coverage of the main issues and those raised by the NUJ. Media takes to innovative story telling As we work from home there’s growing evidence of a revival 21 Saving my A&E in the local economy and a strengthening of the high street A sharp PR learning curve which not that long ago was suffering as consumers opted for large out of town centres. -

Molecular Simulations of New Ammonium-Based Ionic Liquids As Environmentally Acceptable Lubricant Oils Ana Catarina Fernandes Mendonça

Molecular simulations of new ammonium-based ionic liquids as environmentally acceptable lubricant oils Ana Catarina Fernandes Mendonça To cite this version: Ana Catarina Fernandes Mendonça. Molecular simulations of new ammonium-based ionic liquids as environmentally acceptable lubricant oils. Other. Université Blaise Pascal - Clermont-Ferrand II, 2013. English. NNT : 2013CLF22341. tel-00857336 HAL Id: tel-00857336 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00857336 Submitted on 3 Sep 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. N◦ d’ordre: D.U. 2341 UNIVERSITE BLAISE PASCAL U.F.R. Sciences et Technologies ECOLE DOCTORALE DES SCIENCES FONDAMENTALES N◦ 743 THESE present´ ee´ pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR D’UNIVERSITE (Specialit´ e´ : Chimie Physique) Par MENDONC¸A Ana Catarina Master en Chimie Molecular Simulations of New Ammonium-based Ionic Liquids as Environmentally Acceptable Lubricant Oils Simulations moleculaires´ d’une nouvelle classe de liquides ioniques bases´ sur la fonction ammonium pour l’utilisation potentielle en tant qu’huiles lubrifiantes respectueuses de l’environnement Soutenue publiquement le 21 Fevrier´ 2013, devant la commission d’examen: President´ du Jury: Dominic TILDESLEY (Pr-CECAM) Rapporteur: Guillaume GALLIERO (Pr-UPPA) Rapporteur: Mathieu SALANNE (M.C.-UPMC) Directeur: Ag´ılio PADUA´ (Pr-UBP) Co-Directeur: Patrice MALFREYT (Pr-UBP) Examinateur: Susan PERKIN (Dr.-U.Oxford) Acknowledgments This thesis is the work of three years. -

April 2000 – February 2001)

U.S. Commission on National Security/21st Century (click on heading to be linked directly to that section) Phase 1 (July 1998 - August 1999) Major Themes And Implications Supporting Research And Analysis Phase 2 (August 2000 – April 2000) Seeking A National Strategy: A Concert For Preserving Security And Promoting Freedom Phase 3 (April 2000 – February 2001) Roadmap For National Security: Imperative For Change 71730_DAPS.qx 10/12/99 5:06 PM Page #1 NEW WORLD COMING: AMERICAN SECURITY IN THE 21ST CENTURY MAJOR THEMES AND IMPLICATIONS The Phase I Report on the Emerging Global Security Environment for the First Quarter of the 21st Century The United States Commission on National Security/21st Century September 15, 1999 71730_DAPS.qx 10/12/99 5:06 PM Page #3 Preface In 1947, President Harry Truman signed into law the National Security Act, the landmark U.S. national security legislation of the latter half of the 20th century. The 1947 legislation has served us well. It has undergirded our diplomatic efforts, provided the basis to establish our military capa- bilities, and focused our intelligence assets. But the world has changed dramatically in the last fifty years, and particularly in the last decade. Institutions designed in another age may or may not be appropriate for the future. It is the mandate of the United States Commission on National Security/21st Century to examine precise- ly that question. It has undertaken to do so in three phases: the first to describe the world emerging in the first quarter of the next century, the second to design a national security strategy appropri- ate to that world, and the third to propose necessary changes to the national security structure in order to implement that strategy effectively. -

De Diego Otero, Nieves DNI Categoría Actual Como Docente

CV Nieves de Diego Otero Apellidos y nombre: De Diego Otero, Nieves DNI Categoría actual como docente: Catedrática de Universidad Área: Ciencia de materiales e ingeniería metalúrgica Departamento: Departamento de Física de Materiales Facultad: Facultad de Ciencias Físicas Universidad: Universidad Complutense de Madrid Tramos de investigación reconocidos: 6 Tramos de docencia reconocidos: 6 Líneas de investigación: Caracterización de materiales mediante espectroscopia de aniquilación de positrones Simulación de defectos en materiales Participación en Proyectos de I+D financiados en Convocatorias públicas. (nacionales y/o internacionales) Título del proyecto: Improvment of of TEchniques for multiscale Modelling of irradiated materials Entidad financiadora: CEE (Thematic Network 2000/C294/04) Entidades participantes: EDF, University of Liverpool, CNRS-ONERA, ENEA, UPM, SCK-CEN, CEA- Saclay (contractors) Duración, desde: 05.2001 hasta: 05.2005 Cuantía de la subvención: EURO 598.800 Investigador responsable: EDF Número de investigadores participantes: 40 Título del proyecto: Caracterización microestructural y magnética y modelización de intermetálicos, nanoestructuras metálicas y metales hexagonales Entidad financiadora: D.G. de Investigación del MYCT (proyecto nºMAT2002-04087-C02-02) Entidades participantes: UPV-EHU, UCM Duración, desde: 01/11/2002 hasta: 31/10/2005 Cuantía de la subvención: € 40.250 Investigador responsable: Nieves de Diego Otero Número de investigadores participantes: 3 1 Título del proyecto: Simulación por ordenador de -

Volume 40, Number 1 the ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Law.Adelaide.Edu.Au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD

Volume 40, Number 1 THE ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW law.adelaide.edu.au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD The Honourable Professor Catherine Branson AC QC Deputy Chancellor, The University of Adelaide; Former President, Australian Human Rights Commission; Former Justice, Federal Court of Australia Emeritus Professor William R Cornish CMG QC Emeritus Herchel Smith Professor of Intellectual Property Law, University of Cambridge His Excellency Judge James R Crawford AC SC International Court of Justice The Honourable Professor John J Doyle AC QC Former Chief Justice, Supreme Court of South Australia Professor John V Orth William Rand Kenan Jr Professor of Law, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Professor Emerita Rosemary J Owens AO Former Dean, Adelaide Law School The Honourable Justice Melissa Perry Federal Court of Australia Emeritus Professor Ivan Shearer AM RFD Sydney Law School The Honourable Margaret White AO Former Justice, Supreme Court of Queensland Professor John M Williams Dame Roma Mitchell Chair of Law and Former Dean, Adelaide Law School ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Editors Associate Professor Matthew Stubbs and Dr Michelle Lim Book Review and Comment Editor Dr Stacey Henderson Associate Editors Charles Hamra, Kyriaco Nikias and Azaara Perakath Student Editors Joshua Aikens Christian Andreotti Mitchell Brunker Peter Dalrymple Henry Materne-Smith Holly Nicholls Clare Nolan Eleanor Nolan Vincent Rocca India Short Christine Vu Kate Walsh Noel Williams Publications Officer Panita Hirunboot Volume 40 Issue 1 2019 The Adelaide Law Review is a double-blind peer reviewed journal that is published twice a year by the Adelaide Law School, The University of Adelaide. A guide for the submission of manuscripts is set out at the back of this issue. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2006-07 Cover Images

Annual Report and Accounts 2006-07 Cover images Left, from top to bottom: Leading Through Practice, Artwork and Photographs by Reiko Goto, artist and researcher for On The Edge Research. © Reiko Goto 2007. Detail. Detail from Japanese earthenware vase, Meiji 1895. Kyoto, Kin Kozan Sobei VII. Accession number EA1997.41. Image copyright University of Oxford, Ashmolean Museum. Still from Gone with the Wind. Selznick / MGM / The Kobal Collection. Right: View from Töölö bay of Finlandia Hall, Helsinki, the setting for the HERA Conference. Photo: Eero Venhola. The Arts and Humanities Research Council Annual Report and Accounts 2006-2007 Presented to the House of Commons Pursuant to Section 4 of the Higher Education Act 2004 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 12 July 2007 HC 763 LONDON: The Stationery Office £18.00 Part of the orchestral fanfare The The AHRC is incorporated by Royal Charter and came into existence World In One City by Merseyside composer Ian Stephens, which was on 1 April 2005 under the terms of the Higher Education Act 2004. composed to celebrate Liverpool's selection as European Capital of It took over the responsibilities of the Arts and Humanities Research Culture 2008. Image courtesy the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Board. On that date all of the AHRB’s activities, assets and liabilities transferred to the AHRC. The AHRC is a non-departmental public body (NDPB) sponsored by the Office of Science and Innovation (OSI), which is part of the Department for Trade and Industry, along with the other seven research councils. It is governed by its Council, which is responsible for the overall strategic direction of the organisation. -

ISIS Lifetime Impact Study

November 2016 ISIS Lifetime Impact Study Volume 1 – Full Report Paul Simmonds Neil Brown Cristina Rosemberg Peter Varnai Maike Rentel Yasemin Koc Jelena Angelis Kristel Kosk This summary is written by Technopolis in collaboration with STFC www.technopolis-group.com ii ISIS Lifetime Impact Study - Volume 1 technopolis |group|, October 2016 www.technopolis-group.com Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary 2. Introduction 2.1. Introduction to STFC 2.2. Introduction to ISIS 2.3. Conceptual framework 2.4. Overall approach 2.5. Challenges 3. ISIS Research 3.1. Introduction 3.2. Discussion 3.2.1. The economic and social benefits of ISIS research are wide-ranging 3.2.2. ISIS has played an essential and major role in global research endeavours that have and could have significant impacts world-wide 3.2.3. ISIS research has and will continue to produce significant economic impact for the UK 3.2.4. ISIS publications comfortably outperform the UK average 3.2.5. ISIS is critical to academic excellence and UK research quality 3.2.6. Since its inception ISIS has had an innovative approach to instrument design and technology development 3.2.7. ISIS has been essential for the UK’s international reputation 3.3. Summary 4. ISIS Innovation 4.1. Introduction 4.2. Discussion 4.2.1. Industrial use of ISIS is significant; companies now account for 10-15% of total ISIS beam- time 4.2.2. The types of benefits that ISIS provides industry are wide-ranging and across multiple applications 4.2.3. The industrial use of ISIS has and will continue to directly benefit the UK economy 4.2.4. -

College History.Pdf

Exeter College OXFORD Exeter College, Oxford xeter College takes its name not from a man but from a diocese. Its founder, Walter de E Stapeldon, bishop of Exeter, was born about 1266, probably at the hamlet which still bears his name, near Holsworthy, in the remote country of north-west Devon. His family, moderately well-to-do farmers, too grand for peasants and too humble for gentry, had long been prominent in the social life of their locality, but they carried no weight in the county and had probably never been beyond its boundaries. From these unprivileged origins Walter de Stapeldon rose to become not only a bishop but also the treasurer of England, the confidant of King Edward II and eventually the victim of Edward’s enemies. The obscurity of Exeter College his family circumstances makes it impossible to trace the early stages in this adventurous career. We know seen from Turl only that he was an Oxford graduate, rector of Aveton Giffard in South Devon during the 1290s, canon of Street Exeter Cathedral by 1301 and precentor of the Cathedral by 1305. After his election as bishop in 1308 he made rapid progress in the king’s service as a diplomat, archivist and financial expert; and it was his position near the centre of power in a particularly oppressive government which cost him his life in 1326, when Edward II lost his throne and Stapeldon his head. When in 1314 he established Stapeldon Hall, as the College was first known, the bishop’s motives were doubtless mixed: piety, the safety of his soul, and the education of the prospective clergy of his diocese were probably his chief concerns. -

Rosse Papers Summary List: 17Th Century Correspondence

ROSSE PAPERS SUMMARY LIST: 17TH CENTURY CORRESPONDENCE A/ DATE DESCRIPTION 1-26 1595-1699: 17th-century letters and papers of the two branches of the 1871 Parsons family, the Parsonses of Bellamont, Co. Dublin, Viscounts Rosse, and the Parsonses of Parsonstown, alias Birr, King’s County. [N.B. The whole of this section is kept in the right-hand cupboard of the Muniment Room in Birr Castle. It has been microfilmed by the Carroll Institute, Carroll House, 2-6 Catherine Place, London SW1E 6HF. A copy of the microfilm is available in the Muniment Room at Birr Castle and in PRONI.] 1 1595-1699 Large folio volume containing c.125 very miscellaneous documents, amateurishly but sensibly attached to its pages, and referred to in other sub-sections of Section A as ‘MSS ii’. This volume is described in R. J. Hayes, Manuscript Sources for the History of Irish Civilisation, as ‘A volume of documents relating to the Parsons family of Birr, Earls of Rosse, and lands in Offaly and property in Birr, 1595-1699’, and has been microfilmed by the National Library of Ireland (n.526: p. 799). It includes letters of c.1640 from Rev. Richard Heaton, the early and important Irish botanist. 2 1595-1699 Late 19th-century, and not quite complete, table of contents to A/1 (‘MSS ii’) [in the handwriting of the 5th Earl of Rosse (d. 1918)], and including the following entries: ‘1. 1595. Elizabeth Regina, grant to Richard Hardinge (copia). ... 7. 1629. Agreement of sale from Samuel Smith of Birr to Lady Anne Parsons, relict of Sir Laurence Parsons, of cattle, “especially the cows of English breed”.